Jahangir

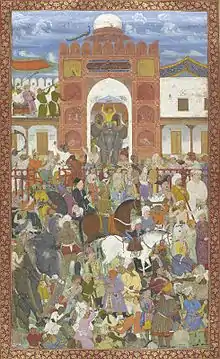

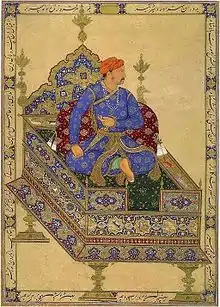

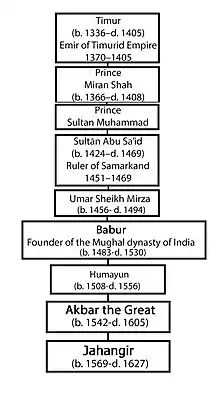

Nur-ud-din Muhammad Salim[4] (Persian: نورالدین محمد سلیم), known by his imperial name Jahangir (Persian: جهانگیر) (31 August 1569 – 28 October 1627),[5] was the fourth Mughal Emperor, who ruled from 1605 until his death in 1627. His imperial name (in Persian) means 'conqueror of the world', 'world-conqueror' or 'world-seizer' (Jahan: world; gir: the root of the Persian verb gereftan: to seize, to grab).

| Nur-ud-din Muhammad Salim Jahangir نور الدین محمد سلیم جہانگیر | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Badshah | |||||

Jahangir. | |||||

| 4th Mughal Emperor | |||||

| Reign | 3 November 1605 – 28 October 1627 | ||||

| Coronation | 24 November 1605 | ||||

| Predecessor | Akbar | ||||

| Successor | Shahryar Mirza | ||||

| Born | Salim 31 August 1569 Fatehpur Sikri, Mughal Empire[1] | ||||

| Died | 28 October 1627 (aged 58) Rajouri, Kashmir, Mughal Empire (now Jammu and Kashmir, India) | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Consort | Saliha Banu Begum Nur Jahan | ||||

| Wives | Shah Begum Jagat Gosain Sahib Jamal Malika Jahan Nur-un-Nisa Begum Khas Mahal Karamsi Saliha Banu Begum | ||||

| Issue | Khusrau Mirza Parviz Mirza Shah Jahan Shahryar Mirza Jahandar Mirza Sultan-un-Nissa Begum Daulat-un-Nissa Begum Bahar Banu Begum Begum Sultan Begum Iffat Banu Begum Five other daughters | ||||

| |||||

| House | Timurid | ||||

| Father | Akbar | ||||

| Mother | Mariam-uz-Zamani | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam[2][3] | ||||

| Mughal emperors | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The fictional tale of his relationship with the Mughal courtesan, Anarkali, has been widely adapted into the literature, art and cinema of India.

Early life

Prince Salim, later Jahangir, was born on 31 August 1569, in Fatehpur Sikri, to Akbar and one of his wives, Mariam-uz-Zamani, daughter of Raja Bharmal of Amber.[6] Akbar's previous children had died in infancy and he had sought the help of holy men to produce a son. Salim was named for one such man, Shaikh Salim, though Akbar always called him Shekhu Baba.[6][7]

Prince Salim succeeded to the throne on Thursday, 3 November 1605, eight days after his father's death. Salim ascended to the throne with the title of Nur-ud-din Muhammad Jahangir Badshah Ghazi, and thus began his 22-year reign at the age of 36. Jahangir, soon after, had to fend off his own son, Prince Khusrau Mirza, when the latter attempted to claim the throne based on Akbar's will to become his next heir. Khusrau Mirza was defeated in 1606 and confined in the fort of Agra. As punishment, Khusrau Mirza was handed over to his younger brother and was partially blinded and killed.[8]

Jahangir considered his third son, Prince Khurram (future Shah Jahan), his favourite. In 1622, Khurram murdered his blind older brother, Khusrau Mirza, in order to smooth his own path to the throne.[9]

Reign

In 1622, Jahangir sent his son, Prince Khurram, to fight against the combined forces of Ahmednagar, Bijapur and Golconda. After his victory, Khurram turned against his father and made a bid for power. As with the insurrection of his eldest son, Khusrau Mirza, Jahangir was able to defeat the challenge from within his family and retain power.[5]

Foreign relations

In 1623, Emperor Jahangir sent his Tahwildar, Khan Alam, to Safavid Persia, accompanied by 800 sepoys, scribes and scholars, along with ten Howdahs well decorated in gold and silver, in order to negotiate peace with Abbas I of Persia after a brief conflict in the region around Kandahar. Khan Alam soon returned with valuable gifts and groups of Mir Shikar (Hunt Masters) from both Safavid Persia and the Khanates of Central Asia.

In 1626, Jahangir began to contemplate an alliance between the Ottomans, Mughals and Uzbeks against the Safavids, who had defeated the Mughals at Kandahar. He even wrote a letter to the Ottoman Sultan, Murad IV. Jahangir's ambition did not materialise, however, due to his death in 1627.

Marriage

Salim was made a Mansabdar of ten thousand (Das-Hazari), the highest military rank of the empire (after the emperor). He independently commanded a regiment in the Kabul campaign of 1581 when he was barely twelve. His Mansab was raised to Twelve Thousand, in 1585, at the time of his betrothal to his cousin Rajkumari Man Bai, daughter of Bhagwant Das of Amer. Bhagwant Das, was the son of Raja Bharmal and the brother of Akbar's Hindu wife and Salim's mother – Mariam-uz-Zamani.[10]

The marriage with Man Bai took place on 13 February 1585. Jahangir named her Shah Begum and she gave birth to Khusrau Mirza. Thereafter, Salim married, in quick succession, a number of accomplished girls from the aristocratic Mughal and Rajput families. One of his early favourite wives was a Rajput Princess, Jagat Gosain Begum. Jahangir named her Taj Bibi Bilqis Makani and she gave birth to Prince Khurram, the future Shah Jahan, who was Jahangir's successor to the throne. On 7 July 1586 he married a daughter of Raja Rai Singh, Maharaja of Bikaner. In July 1586, he married Malika Shikar Begum, daughter of Sultan Abu Said Khan Jagatai, Sultan of Kashghar. In 1586, he married Sahib-i-Jamal Begum, daughter of Khwaja Hassan of Herat, a cousin of Zain Khan Koka. In 1587, he married Malika Jahan Begum, daughter of Bhim Singh, Maharaja of Jaisalmer. He also married the daughter of Raja Darya Malbhas. In October 1590, he married Zohra Begum, daughter of Mirza Sanjar Hazara. In 1591, he married Karamnasi Begum, daughter of Raja Kesho Das Rathore of Mertia. On 11 January 1592, he married Kanwal Rani, daughter of Ali Sher Khan, by his wife, Gul Khatun. In October 1592, he married a daughter of Husain Chak of Kashmir. In January/March 1593, he married Nur un-nisa Begum, daughter of Ibrahim Husain Mirza, by his wife, Gulrukh Begum, daughter of Kamran Mirza. In September 1593, he married a daughter of Ali Khan Faruqi, Raja of Khandesh. He also married a daughter of Abdullah Khan Baluch. On 28 June 1596, he married Khas Mahal Begum, daughter of Zain Khan Koka, Subadar of Kabul and Lahore. In 1608, he married Saliha Banu Begum, daughter of Qasim Khan, a senior member of the Imperial Household. On 17 June 1608, he married Koka Kumari Begum, eldest daughter of Jagat Singh, Yuvraj of Amber.

Jahangir married the extremely beautiful and intelligent Mehr-un-Nisaa (better known by her subsequent title of Nur Jahan) on 25 May 1611. She was the widow of Sher Afgan. Mehr-un-Nisaa became his indisputable chief consort and favourite wife immediately after their marriage. She was witty, intelligent and beautiful, which was what attracted Jahangir to her. Before being awarded the title of Nur Jahan ('Light of the World'), she was called Nur Mahal ('Light of the Palace'). Her abilities are said to range from fashion designing to hunting. There is also a myth that she had once killed four tigers with six bullets.

Nur Jahan

Mehr-Un-Nisa, or Nur Jahan, occupies an important place in the history of Jahangir. She was the widow of a rebel officer, Sher Afgan, whose actual name was Ali Quli Beg Ist'ajlu. He had earned the title "Sher Afgan" (Tiger tosser) from Emperor Akbar after throwing off a tiger that had leaped to attack Akbar on the top of an elephant in a royal hunt at Bengal and then stabbing the fallen tiger to death. Akbar was greatly affected by the bravery of the young Turkish bodyguard accompanying him and awarded him the captaincy of the Imperial Guard at Burdwan, Bengal. Sher Afgan had killed in rebellion (after having learned of Jahangir's orders to have him slain to possess his beautiful wife Mehr Un Nisaa as Jahangir yearned for her much earlier than her wedding to Sher Afgan), the governor of Bengal Qutubuddin Koka who was instructed secretly by Jahangir in his quest and who also was the emperor's foster brother and Sheikh Salim Chishti's grandson and consequently had been slain by the guards of the Governor. The widowed Mehr-Un-Nisaa was brought to Agra along with her nine-year-old daughter and placed in—or refused to be placed in—the Royal harem in 1607. Jahangir married her in 1611 and gave her the title of Nur Jahan or "Light of the World". It was rumoured that Jahangir had a hand in the death of her first husband Sher Afghan, albeit there is no recorded evidence to prove that he was guilty of that crime; in fact most travellers' reports say that he met her after Sher Afgan's death. (See Ellison Banks Findly's scholarly biography for a full discussion.)

The loss of Kandahar was due to Prince Khurram's refusal to obey her orders. When the Persians besieged Kandahar, Nur Jahan was at the helm of affairs. She ordered Prince Khurram to march for Kandahar, but he refused to do so. There is no doubt that his refusal was due to her behaviour towards him, as she was favouring her son-in-law, Shahryar, at the expense of Khurram. Khurram suspected that in his absence, Shahryar might be given promotion and that he might die on the battlefield. This fear forced Khurram to rebel against his father rather than fight against the Persians, and thereby Kandahar was lost to the Persians. Nur Jahan struck coins in her own name during the last years of Jahangir's reign when he was taken ill.

Under Jahangir, the empire continued to be a war state attuned to conquest and expansion. Jahangir's most irksome foe was the Rana of Mewar, Amar Singh, who finally surrendered in 1613 to Khurram's forces. In the northeast, the Mughals clashed with the Ahoms of Assam, whose guerilla tactics gave the Mughals a hard time. In Northern India, Jahangir's forces under Khurram defeated their other principal adversary, the Raja of Kangra, in 1615; in the Deccan, his victories further consolidated the empire. But in 1620, Jahangir fell sick, and so ensued the familiar quest for power. Nur Jahan married her daughter to Shahryar, Jahangir's youngest son from his other queen, in the hope of having a living male heir to the throne when Jahangir died.

Conquests

In the year 1594, Jahangir was dispatched by his father, the Emperor Akbar, alongside Abu'l-Hasan Asaf Khan, also known as Mirza Jafar Beg son of Mirza Ghiyas Beg Isfahani and brother of Nur Jahan, and Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak, to defeat the renegade Vir Singh Deo of Bundela and capture the city of Orchha, which was considered the centre of the revolt. Jahangir arrived with a force of 12,000 after many ferocious encounters and finally subdued the Bundela and ordered Vir Singh Deo to surrender. After tremendous casualties and the start of negotiations between the two, Vir Singh Deo handed over 5000 Bundela infantry and 1000 cavalry, but he feared Mughal retaliation and remained a fugitive until his death. The victorious Jahangir, at 26 years of age, ordered the completion of the Jahangir Mahal a famous Mughal citadel in Orchha to commemorate and honour his victory.

Jahangir then gathered his forces under the command of Ali Kuli Khan and fought Lakshmi Narayan of Koch Bihar. Lakshmi Narayan then accepted the Mughals as his suzerains and was given the title Nazir, later establishing a garrison at Atharokotha.

In 1613,[11] the Portuguese seized the Mughal ship Rahimi, which had set out from Surat on its way with a large cargo of 100,000 rupees and Pilgrims, who were on their way to Mecca and Medina in order to attend the annual Hajj. The Rahimi was owned by Mariam-uz-Zamani, mother of Jahangir and Akbar's Rajput wife. She was referred to as Queen mother of Hindustan during his reign. Rahimi was the largest Indian ship sailing in the Red Sea and was known to the Europeans as the "great pilgrimage ship". When the Portuguese officially refused to return the ship and the passengers, the outcry at the Mughal court was unusually severe. The outrage was compounded by the fact that the owner and the patron of the ship was none other than the revered mother of the current emperor. Jahangir himself was outraged and ordered the seizure of the Portuguese town Daman. He ordered the apprehension of all Portuguese within the Mughal Empire; he further confiscated churches that belonged to the Jesuits. This episode is considered to be an example of the struggle for wealth that would later ensue and lead to colonisation of the Indian sub-continent.

Jahangir was responsible for ending a century long struggle with the state of Mewar. The campaign against the Rajputs was pushed so extensively that they were made to submit with great loss of life and property.

Jahangir posted Islam Khan I to subdue Musa Khan, an Afghan rebel in Bengal, in 1608. Jahangir also thought of capturing Kangra Fort, which Akbar had failed to do in 1615. Consequently, a siege was laid and the fort was taken in 1620, which "resulted in the submission of the Raja of Chamba who was the greatest of all the rajas in the region." The district of Kistwar, in the state of Kashmir, was also conquered.

Death

Jahangir was trying to restore his health by visiting Kashmir and Kabul. He went from Kabul to Kashmir but decided to return to Lahore because of a severe cold.

Jahangir died on the journey from Kashmir to Lahore, near Sarai Saadabad in Bhimber in 1627.[12] To embalm and preserve his body, the entrails were removed; these were buried inside Baghsar Fort near Bhimber in Kashmir. The body was then conveyed by palanquin to Lahore and was buried in Shahdara Bagh, a suburb of that city. The elegant mausoleum is today a popular tourist attraction site.

Jahangir was succeeded by his third son, Prince Khurram, who took the regnal name Shah Jahan.

Religion

Sir Thomas Roe was England's first ambassador to the Mughal court. Relations with England turned tense in 1617 when Roe warned Jahangir that if the young and charismatic Prince Shah Jahan, newly instated as the Subedar of Gujarat, turned the English out of the province, "then he must expect we would do our justice upon the seas". Shah Jahan chose to seal an official Firman allowing the English to trade in Gujarat in the year 1618.

Many contemporary chroniclers were not sure how to describe Jahangir's personal belief structure. Roe labelled him an atheist, and although most others shied away from that term, they did not feel as though they could call him an orthodox Sunni. Roe believed Jahangir's religion to be of his own making, "for he envies [the Prophet] Mohammed, and wisely sees no reason why he should not be as great a prophet as he and therefore professed himself so... he hath found many disciples that flatter or follow him." At this time, one of those disciples happened to be the current English ambassador, though his initiation into Jahangir's inner circle was devoid of religious significance for Roe, as he did not understand the full extent of what he was doing. Jahangir hung "a picture of himself set in gold hanging at a wire gold chain" around Roe's neck. Roe thought it "an special favour, for all the great men that wear the King's image (which none may do but to whom it is given) receive no other than a medal of gold as big as six pence."[13]:214–15

Had Roe intentionally converted, it would have caused quite a scandal in London. But since there was no intent, there was no resultant problem. Such disciples were an elite group of imperial servants, with one of them being promoted to Chief Justice. However, it is not clear that any of those who became disciples renounced their previous religion, so it is probable to see this as a way in which the emperor strengthened the bond between himself and his nobles. Despite Roe's somewhat casual use of the term 'atheist', he could not quite put his finger on Jahangir's real beliefs. Roe lamented that the emperor was either "the most impossible man in the world to be converted, or the most easy; for he loves to hear, and hath so little religion yet, that he can well abide to have any derided."

This should not imply that the multi-confessional state appealed to all, or that all Muslims were happy with the situation in India. In a book written on statecraft for Jahangir, the author advised him to direct "all his energies to understanding the counsel of the sages and to comprehending the intimations of the 'ulama.'" At the start of his regime many staunch Sunnis were hopeful, because he seemed less tolerant of other faiths than his father had been. At the time of his accession and the elimination of Abu'l Fazl, his father's chief minister and the architect of his eclectic religious stance, a powerful group of orthodox noblemen had gained increased power in the Mughal court.

Most notorious was the execution of the Sikh Guru Arjan Dev, whom Jahangir had had killed in prison. His lands were confiscated and his sons imprisoned as Jahangir suspected him of helping Khusrau's rebellion.[14] It is unclear whether Jahangir even understood what a Sikh was, referring to Guru Arjan as a Hindu, who had "captured many of the simple-hearted of the Hindus and even of the ignorant and foolish followers of Islam, by his ways and manners... for three or four generations (of spiritual successors) they had kept this shop warm." The trigger for Guru Arjan's execution was his support for Jahangir's rebel son Khusrau Mirza, yet it is clear from Jahangir's own memoirs that he disliked Guru Arjan before then: "many times it occurred to me to put a stop to this vain affair or bring him into the assembly of the people of Islam."[15]

Jahangir also moved swiftly to persecute Jains. One of his court historians states, “One day at Ahmadabad it was reported that many of the infidel and superstitious sect of the Seoras [Jains] of Gujarat had made several very great and splendid temples, and having placed in them their false gods, had managed to secure a large degree of respect for themselves and that the women who went for worship in those temples were polluted by them and other people. The Emperor Jahangir ordered them banished from the country, and their temples to be demolished.”[16]

In another story narrated by Jahangir himself in his memoir, Jahangir visited Pushkar and was shocked to find a temple of a boar like deity. He was quite taken-aback. "The worthless religion of the Hindus is this," he claimed and ordered his men to destroy the idol. He also heard about a jogi doing mysterious things and he ordered his men to evict him and have the place destroyed.[17][18]

Muqarrab Khan sent to Jahangir "a European curtain (tapestry) the like of which in beauty no other work of the Frank [European] painters has ever been seen." One of his audience halls was "adorned with European screens." Christian themes attracted Jahangir, and even merited a mention in the Tuzuk. One of his slaves gave him a piece of ivory into which had been carved four scenes. In the last scene "there is a tree, below which the figure of the revered (hazrat) Jesus is shown. One person has placed his head at Jesus' feet, and an old man is conversing with Jesus and four others are standing by." Though Jahangir believed it to be the work of the slave who presented it to him, Sayyid Ahmad and Henry Beveridge suggest that it was of European origin and possibly showed the Transfiguration. Wherever it came from, and whatever it represented, it was clear that a European style had come to influence Mughal art, otherwise the slave would not have claimed it as his own design, nor would he have been believed by Jahangir.

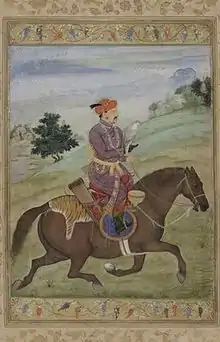

Art

Jahangir was fascinated with art and architecture. In his autobiography, the Jahangirnama, Jahangir recorded events that occurred during his reign, descriptions of flora and fauna that he encountered, and other aspects of daily life, and commissioned court painters such as Ustad Mansur to paint detailed pieces that would accompany his vivid prose.[19] For example, in 1619, he put pen to paper in awe of a royal falcon delivered to his court from the ruler of Iran: “What can I write of the beauty of this bird’s color? It had black markings, and every feather on its wings, back, and sides was extremely beautiful,” and then recorded his command that Ustad Mansur paint a portrait of it after it perished.[20] Jahangir bound and displayed much of the art that he commissioned in elaborate albums of hundreds of images, sometimes organized around a theme such as zoology.[21]

Jahangir himself was far from modest in his autobiography when he stated his prowess at being able to determine the artist of any portrait by simply looking at a painting. As he said:

...my liking for painting and my practice in judging it have arrived at such point when any work is brought before me, either of deceased artists or of those of the present day, without the names being told me, I say on the spur of the moment that is the work of such and such a man. And if there be a picture containing many portraits and each face is the work of a different master, I can discover which face is the work of each of them. If any other person has put in the eye and eyebrow of a face, I can perceive whose work the original face is and who has painted the eye and eyebrow.

Jahangir took his connoisseurship of art very seriously. He also preserved paintings from Emperor Akbar's period. An excellent example of this is the painting done by Ustad Mansur of Musician Naubat Khan, son in law of legendary Tansen. In addition to their aesthetic qualities, paintings created under his reign were closely catalogued, dated and even signed, providing scholars with fairly accurate ideas as to when and in what context many of the pieces were created.

In the foreword to W. M. Thackston’s translation of the Jahangirnama, Milo Cleveland Beach explains that Jahangir ruled during a time of considerably stable political control, and had the opportunity to order artists to create art to accompany his memoirs that were “in response to the emperor’s current enthusiasms”.[22] He used his wealth and his luxury of free time to chronicle, in detail, the lush natural world that the Mughal Empire encompassed. At times, he would have artists travel with him for this purpose; when Jahangir was in Rahimabad, he had his painters on hand to capture the appearance of a specific tiger that he shot and killed, because he found it to be particularly beautiful.[23]

The Jesuits had brought with them various books, engravings, and paintings and, when they saw the delight Akbar held for them, sent for more and more of the same to be given to the Mughals. They felt the Mughals were on the "verge of conversion", a notion which proved to be very false. Instead, both Akbar and Jahangir studied this artwork very closely and replicated and adapted it, adopting much of the early iconographic features and later the pictorial realism for which Renaissance art was known. Jahangir was notable for his pride in the ability of his court painters. A classic example of this is described in Sir Thomas Roe's diaries, in which the Emperor had his painters copy a European miniature several times creating a total of five miniatures. Jahangir then challenged Roe to pick out the original from the copies, a feat Sir Thomas Roe could not do, to the delight of Jahangir.

Jahangir was also revolutionary in his adaptation of European styles. A collection at the British Museum in London contains seventy-four drawings of Indian portraits dating from the time of Jahangir, including a portrait of the emperor himself. These portraits are a unique example of art during Jahangir's reign because faces were not drawn in full, including the shoulders as well as the head as these drawings are.‘’ [24]

Criticism

Jahangir is widely considered to have been a weak and incapable ruler.[25][26][27][28] Orientalist Henry Beveridge (editor of the Tuzk-e-Jahangiri) compares Jahangir to the Roman emperor Claudius, for both were "weak men... in their wrong places as rulers... [and had] Jahangir been head of a Natural History Museum,... [he] would have been [a] better and happier man."[29] Sir William Hawkins, who visited Jahangir's court in 1609, said: "In such short that what this man's father, called Ecber Padasha [Badshah Akbar], got of the Deccans, this king, Selim Sha [Jahangir] beginneth to lose."[29] Italian writer and traveller, Niccolao Manucci, who worked under Jahangir's grandson, Dara Shikoh, began his discussion of Jahangir by saying: "It is a truth tested by experience that sons dissipate what their fathers gained in the sweat of their brow."[29]

According to John F. Richards, Jahangir's frequent withdrawal to a private sphere of life was partly reflective of his indolence, brought on by his addiction to a considerable daily dosage of wine and opium.[30]

In media

_and_his_legendary_illicit_love.jpg.webp)

- In the 1939 Hindi film Pukar, Jehangir was portrayed by Chandra Mohan.[31]

- In the 1953 Hindi film Anarkali, he was portrayed by Pradeep Kumar.[32]

- In the 1955 Telugu film Anarkali, he was portrayed by ANR

- In the 1960 Hindi film Mughal-e-Azam, he was portrayed by Dilip Kumar.[33] Jalal Agha also played the younger Jahangir at the start of the film.[33]

- In the 1966 Malyalam film Anarkali, he was portrayed by Prem Nazir.[34]

- In the 1979 Telugu film Akbar Salim Anarkali, he was portrayed by Balakrishna

- In the 1988 Shyam Benegal's TV Series Bharat Ek Khoj, he was portrayed by Vijay Arora

- In the 2000 TV series Noorjahan, he was portrayed by Milnd Soman.[35]

- In the 2013 Ekta Kapoor's TV Series Jodha Akbar, he was portrayed by Ravi Bhatia. Ayaan Zubair Rahmani also played young Salim initially.

- In the 2014 Indu Sudaresan's TV Series Siyaasat, he was portrayed by Karanvir Sharma and Later Sudhanshu Pandey.[36]

- In the 2014 Indian television sitcom Har Mushkil Ka Hal Akbar Birbal, Pawan Singh portrayed the role of prince Salim.

- In the 2018 Colors TV series Dastaan-E-Mohabbat Salim Anarkali, he is portrayed by Shaheer Sheikh

- In the 2020 Indian comedy television show Akbar Ka Bal Birbal, the role of the prince was again essayed by Pawan Singh.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Jahangir | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Works online

- Emperor of Hindustan, Jahangir (1829). Memoirs of the Emperor Jahangueir. Translated by Price, David. London: J. Murray.

- Elliot, Henry Miers (1875). Wakiʼat-i Jahangiri. Lahore: Sheikh Mubarak Ali.

See also

References

- Henry Beveridge, Akbarnama of Abu'l Fazl Volume II (1907), p. 503

- Andrew J. Newman, Twelver Shiism: Unity and Diversity in the Life of Islam 632 to 1722 (Edinburgh University Press, 2013), online version: p. 48: "Jahangir [was] ... a Sunni."

- John F. Richards, The Mughal Empire (Cambridge University Press, 1995), p. 103

- Singh, Pashaura; Fenech, Louis E., eds. (2014). The Oxford handbook of Sikh studies. Oxford University Press. p. 647. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- "Jahāngīr". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- Jahangir (1909–1914). The Tūzuk-i-Jahangīrī Or Memoirs Of Jahāngīr. Translated by Alexander Rogers; Henry Beveridge. London: Royal Asiatic Society. p. 1. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- Eraly, Abraham (2000). Emperors of the Peacock Throne: The Saga of the Great Mughals. Penguin Books India. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-14-100143-2.

- "The Internationalization of Portuguese Historiography". brown.edu. Archived from the original on 14 May 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- Ellison Banks Findly (1993). Nur Jahan: Empress of Mughal India. Oxford University Press. pp. 170–172. ISBN 978-0-19-536060-8.

- Rahman, Munibur. "Salīm, Muḥammad Ḳulī". Encyclopédie de l'Islam. BRILL. doi:10.1163/9789004206106_eifo_sim_6549.

- Sekhara Bandyopadhyaya (2004). From Plassey to Partition: A History of Modern India. Orient Blackswan. p. 37. ISBN 978-81-250-2596-2.

- Allan, J. (1958). Muslim India. The Cambridge Shorter History of India (in German). S. Chand. p. 311. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- Roe, Sir Thomas (1899). Foster, W (ed.). The Embassy of Sir Thomas Roe to the Court of the Great Mughal (Rev. 1926 ed.). London: Humphrey Milford.

- Wynbrandt, James (2009). A Brief History of Pakistan. Infobase Publishing. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-0-8160-6184-6.

- Goel, The Story of Islamic Imperialism in India, 59.

- Shourie et al., Hindu Temples, 272.

- Shourie et al., Hindu Temples, 266.

- Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri, translated into English by Alexander Rogers, first published 1909-1914, New Delhi Reprint, 1978, Vol. I, pp. 254-55

- Cleveland Beach, Milo (1992). Mughal and Rajput Painting. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 90.

- Jahangir (1999). The Jahangirnama: Memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India. Translated by Thackston, W.M. New York: Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Association with Oxford University Press. pp. 314.

- Cleveland Beach, Milo (1992). Mughal and Rajput Painting. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 82.

- Jahangir (1999). The Jahangirnama: Memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India. Translated by Thackston, W.M. New York: Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Association with Oxford University Press. pp. vii.

- Verma, Som Prakash (1999). Mughal Painter of Flora and Fauna: Ustād Manṣūr. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications. p. 25.

- Losty, J.P. (2013). Sharma, M; Kaimal, P (eds.). The Carpet at the Window: a European Motif in the Mughal Jharokha Portrait. Indian Painting: Themes, History and Interpretations; Essays in Honour of B.N. Goswamy. Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing. p. 52-64.

- Lach, Donald F.; Kley, Edwin J. Van (1998). Asia in the Making of Europe Vol. III, Bk. 2: A Century of Advance, South Asia (Pbk. ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 629. ISBN 978-0-226-46767-2.

- Flores, Jorge (2015). The Mughal Padshah: A Jesuit Treatise on Emperor Jahangir's Court and Household. Brill. p. 9. ISBN 978-9004307537.

- Robinson, Annemarie Schimmel ; translated by Corinne Attwood ; edited by Burzine K. Waghmar ; with a foreword by Francis (2005). The empire of the Great Mughals : history, art and culture (Revised ed.). Lahore: Sang-E-Meel Pub. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-86189-185-3.

- Hansen, Valerie; Curtis, Ken (2013). Voyages in World History, Volume 1 to 1600. Cengage Learning. p. 446. ISBN 978-1-285-41512-3.

- Findly, Ellison Banks (1993). Nur Jahan, empress of Mughal India. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 311. ISBN 978-0-19-536060-8.

- Richards, John F (2008). The New Cambridge History of India: Mughal Empire. Delhi: Cambridge University Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-81-85618-49-4.

- Bajaj, J. K. (2014). On & Behind the Indian Cinema. Diamond Pocket Books Pvt Ltd. p. 2020. ISBN 9789350836217.

- U, Saiam Z. (2012). Houseful The Golden Years of Hindi Cinema. Om Books International. ISBN 9789380070254.

- "Mughal-E-Azam: Lesser known facts". The Times of India. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- Vijaykumar, B. (31 May 2010). "Anarkali 1966". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- Vetticad, Anna M. M. (27 September 1999). "Model Milind Soman to play Salim in serial Noorjahan on DD1". India Today. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- Kotwani, Hiren (20 March 2015). "Sudhanshu Pandey replaces Karanvir Sharma in Siyaasat". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- John E Woods, The Timurid Dynasty (1990), pp. 38–39

- Jahangir (1909–1914, p. 1)

- Dr. B. P. Saha (1997). Begams, concubines, and memsahibs. Vikas Pub. House. p. 20.

- Sarkar, J. N. (1994) [1984]. A History of Jaipur (Reprinted ed.). Orient Longman. pp. 31–34. ISBN 81-250-0333-9.

- Syad Muhammad Latif, Agra: Historical and descriptive with an account of Akbar and his court and of the modern city of Agra (2003), p. 156

- Jadunath Sarkar, A History of Jaipur (1994), p. 43

- C. M. Agrawal, Akbar and his Hindu officers: a critical study (1986), p. 27

Further reading

- Andrea, Alfred J.; Overfield, James H. (2005). The Human Record: Sources of Global History. Vol. 2: Since 1500 (Fifth ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-618-37041-2.

- Alvi, Sajida S. (1989). "Religion and State during the Reign of Mughal Emperor Jahǎngǐr (1605–27): Nonjuristical Perspectives". Studia Islamica (9): 95–119. doi:10.2307/1596069. JSTOR 1596069.

- Balabanlilar, Lisa (2020). The Emperor Jahangir: Power and Kingship in Mughal India. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 9781838600426.

- Findly, Ellison B. (April–June 1987). "Jahāngīr's Vow of Non-Violence". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 107 (2): 245–256. doi:10.2307/602833. JSTOR 602833.

- Gascoigne, Bamber, and Christina Gascoigne. The Great Moghuls. London: Constable, 1998. pp. 130–179.

- Lefèvre, Corinne (2007). "Recovering a Missing Voice from Mughal India: The Imperial Discourse of Jahāngīr (r. 1605–1627) in his Memoirs" (PDF). Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 50 (4): 452–489. doi:10.1163/156852007783245034.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Jahangir |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jahangir. |

- Works by Jahangir at Project Gutenberg

- Jehangir and Shah Jehan

- The World Conqueror: Jahangir

- Jains and the Mughals

Jahangir Born: 20 September 1569 Died: 8 November 1627 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Akbar |

Mughal Emperor 1605–1627 |

Succeeded by Shah Jahan |