Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent

Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent mainly took place from the 12th to the 16th centuries, though earlier Muslim conquests include the invasions into modern Pakistan and the Umayyad campaigns in India, during the time of the Rajput kingdoms in the 8th century.

| Outline of South Asian history |

|---|

_without_national_boundaries.svg.png.webp) |

Mahmud of Ghazni, the first ruler to hold the title Sultan, who preserved an ideological link to the suzerainty of the Abbasid Caliphate, invaded and plundered vast parts of Punjab, Gujarat, starting from the Indus River, during the 10th century.[1][2]

After the capture of Lahore and the end of the Ghaznavids, the Ghurid Empire ruled by Muhammad of Ghor and Ghiyath al-Din Muhammad laid the foundation of Muslim rule in India. In 1206, Bakhtiyar Khalji led the Muslim conquest of Bengal, marking the easternmost expansion of Islam at the time. The Ghurid Empire soon evolved into the Delhi Sultanate ruled by Qutb al-Din Aibak, the founder of the Mamluk dynasty. With the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate, Islam was spread across most parts of the Indian subcontinent.

In the 14th century, the Khalji dynasty, under Alauddin Khalji, temporarily extended Muslim rule southwards to Gujarat, Rajasthan and the Deccan, while the Tughlaq dynasty temporarily expanded its territorial reach till Tamil Nadu. The break up of the Delhi Sultanate resulted in several Muslim sultanates and dynasties to emerge across the Indian subcontinent, such as the Gujarat Sultanate, Malwa Sultanate, the Bahmani Sultanate and the wealthy Bengal Sultanate, a major trading nation in the world.[3][4] Some of these were however followed by Hindu re-conquests and resistance from the native powers, and states such as the Kamma Nayakas, Vijayanagaras, Gajapatis, Cheros and Rajput states.

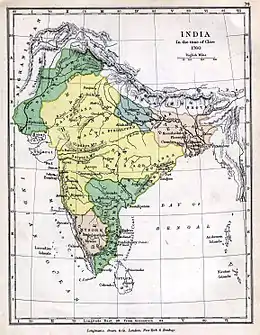

Prior to the full rise of the Mughal Empire founded by Babur, one of the gunpowder empires, which annexed almost all of the ruling elites of the whole of South Asia, the Sur Empire ruled by Sher Shah Suri conquered large territories in the northern parts of India. Akbar gradually enlarged the Mughal Empire to include nearly all of South Asia, but the zenith was reached in the end of the 17th century, when the reign under emperor Aurangzeb witnessed the full establishment of Islamic sharia through the Fatawa-e-Alamgiri.[5][6]

The Mughals suffered a massive decline in the early 18th century after Afsharid ruler Nader Shah's invasion, an unexpected attack that demonstrated the weakness of the Mughal Empire.[7] This provided opportunities for the powerful Mysore Kingdom, Nawabs of Bengal and Murshidabad, Maratha Empire, Sikh Empire, Nizams of Hyderabad to exercise control over large regions of the Indian subcontinent.[8]

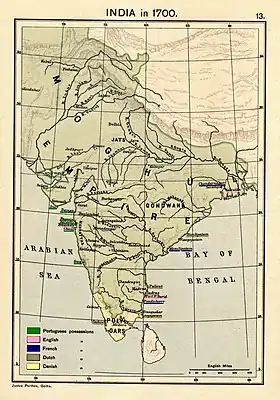

After the Battle of Plassey, Battle of Buxar and the long Anglo-Mysore Wars, the East India Company ended up seizing control of the entire Indian subcontinent. By the end of the 18th century, European powers, mainly the British Empire, commenced to extend political influence over the Indian subcontinent, and by the end of the 19th century, much of the Indian subcontinent, came under European colonial domination, most notably the British Raj.

Early Muslim presence

Islam in South Asia existed in communities along the Arab coastal trade routes in Sindh, Bengal, Gujarat, Kerala, and Ceylon as soon as the religion originated and had gained early acceptance in the Arabian Peninsula, though the first incursion by the new Muslim successor states of the Arab World occurred around 636 CE or 643 AD, during the Rashidun Caliphate, long before any Arab army reached the frontier of India by land.

Shortly after the Muslim conquest of Persia the connection between the Sind and Islam was established by the initial Muslim missions during the Rashidun Caliphate. Al-Hakim ibn Jabalah al-Abdi, who attacked Makran in the year 649 AD, was an early partisan of Ali ibn Abu Talib.[9] During the caliphate of Ali, many Hindus of Sindh had come under the influence of Shi'ism[10] and some even participated in the Battle of Camel and died fighting for Ali.[9] Under the Umayyads (661 – 750 AD), many Shias sought asylum in the region of Sindh, to live in relative peace in the remote area. Ziyad Hindi was one of those refugees.[11]

Arab naval expeditions

Uthman b. Abul As Al Sakifi, governor of Bahrain and Oman, sent out ships to raid Thane, near modern-day Mumbai, while his brother Hakam sailed to Broach and a third fleet sailed to Debal under his younger brother Mughira either in 636 CE or 643 AD. According to one source all three expeditions were successful,[12] however, another source states Mughira was defeated and killed at Debal.[13] These expeditions were sent without the Caliph Umar's consent, and he rebuked Uthman, saying that had the Arabs lost any men the Caliph would have killed an equal number of men from Utham's tribe in retaliation.[12] The expeditions were sent to attack pirate nests, to safeguard Arabian trade in the Arabian Sea, and not to start the conquest of India.[14][15][16]

Rashidun Caliphate and the Indian frontier

The kingdoms of Kapisa-Gandhara in modern-day Afghanistan, Zabulistan and Sindh (which then held Makran) in modern-day Pakistan, all of which were culturally and politically part of India since ancient times,[17] were known as "The Frontier of Al Hind". The first clash between a ruler of an Indian kingdom and the Arabs took place in 643 AD, when Arab forces defeated Rutbil, King of Zabulistan in Sistan.[18] Arabs led by Suhail b. Abdi and Hakam al Taghilbi defeated an Indian army in the Battle of Rasil in 644 AD at the Indian Ocean sea coast,[19] then reached the Indus River. Caliph Umar ibn Al-Khattab denied them permission to cross the river or operate on Indian soil and the Arabs returned home.[20]

Abdullah ibn Aamir led the invasion of Khurasan in 650 AD, and his general Rabi b. Ziyad Al Harithi attacked Sistan and took Zaranj and surrounding areas in 651 AD[21] while Ahnaf ibn Qais conquered the Hepthalites of Herat in 652 AD and advanced up to Balkh by 653 AD. Arab conquests now bordered the Kingdoms of Kapisa, Zabul and Sindh in modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan. The Arabs levied annual tributes on the newly captured areas, and leaving 4,000 men garrisons at Merv and Zaranj retired to Iraq instead of pushing on against the frontier of India.[22] Caliph Uthman b. Affan sanctioned an attack against Makran in 652 AD, and sent a recon mission to Sindh in 653 AD. The mission described Makran as inhospitable, and Caliph Uthman, probably assuming the country beyond was much worse, forbade any further incursions into India.[23][24]

This was the beginning of a prolonged struggle between the rulers of Kabul and Zabul against successive Arab governors of Sistan, Khurasan and Makran in modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan. The Kabul Shahi kings and their Zunbil kinsmen blocked access to the Khyber Pass and Gomal Pass routes into India from 653 to 870 AD,[25] while modern Balochistan, Pakistan, comprising the areas of Kikan or Qiqanan, Nukan, Turan, Buqan, Qufs, Mashkey and Makran, would face several Arab expeditions between 661 – 711 AD.[26] The Arabs launched several raids against these frontier lands, but repeated rebellions in Sistan and Khurasan between 653 – 691 AD diverted much of their military resources in order to subdue these provinces and away from expansion into Al Hind. Muslim control of these areas ebbed and flowed repeatedly as a result until 870 AD. Arabs troops disliked being stationed in Makran,[27] and were reluctant to campaign in the Kabul area and Zabulistan due to the difficult terrain and underestimation of Zunbil's power.[28] Arab strategy was tribute extraction instead of systematic conquest. The fierce resistance of Zunbil and Turki Shah stalled Arab progress repeatedly in the "Frontier Zone".[29][30]

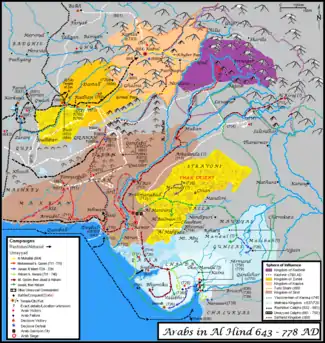

Umayyad expansion in Al Hind

Muawiyah established Umayyad rule over the Arabs after the first First Fitna in 661 AD, and resumed expansion of the Muslim Empire. After 663/665 AD, the Arabs launched an invasion against Kapisa, Zabul and what is now Pakistani Balochistan. Abdur Rahman b. Samurra besieged Kabul in 663 AD, while Haris b Marrah advanced against Kalat after marching through Fannazabur and Quandabil and moving through the Bolan Pass. King Chach of Sindh sent an army against the Arabs, the enemy blocked the mountain passes, Haris was killed and his army was annihilated. Al-Muhallab ibn Abi Sufra took a detachment through the Khyber pass towards Multan in Southern Punjab in modern-day Pakistan in 664 AD, then pushed south into Kikan, and may have also raided Quandabil. Turki Shah and Zunbil expelled Arabs from their respective kingdoms by 670 AD, and Zunbil began assisting in organizing resistance in Makran.[19]

Battles in Makran and Zabulistan

Arabs launched several campaigns in eastern Balochistan between 661 – 681 AD, four Arab commanders were killed during the campaigns, but Sinan b. Salma managed to conquer parts of Makran including the Chagai area,[31] and establish a permanent base of operations in 673 AD.[32] Rashid b. Amr, the next governor of Makran, subdued Mashkey in 672 AD,[33] Munzir b. Jarood Al Abadi managed to garrison Kikan and conquer Buqan by 681 AD, while Ibn Harri Al Bahili, conducted several campaigns to secure the Arab hold on Kikan, Makran and Buqan by 683 AD.[34][35] Zunbil saw off Arab campaigns in 668, 672 and 673 AD by paying tribute, although Arabs occupied the areas south of Helmand in 673 AD permanently[32][36] Zunbil defeated Yazid b. Salm's army in 681 AD at Junzah, and Arabs had to pay 500,000 dirhams to ransom their prisoners,[37] but the Arabs defeated and killed Zunbil in Sistan in 685. The Arabs were defeated in Zabul in next invaded Zabul in 693 AD.[38]

Al Hajjaj and the East

Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf Al Thaqifi, who had played a crucial role during the Second Fitna for the Umayyad cause, was appointed the governor of Iraq in 694 AD, further extended to Khurasan and Sistan in 697 AD. Al-Hajjaj also sponsored Muslim expansion in Makran, Sistan, Transoxiana and Sindh.[39][40]

Campaigns in Makran and Zabul

Arab hold on Makran had weakened when Arab rebels seized the province, and Hajjaj had to send three governors between 694 – 707 AD before Makran was partially recovered by 694 AD.[29] Al Hajjaj also fought Zunbil in 698 AD and 700 AD. The 20,000 strong army led by Ubaidullah ibn Abu Bakra was trapped by the armies of Zunbil and Turki Shah near Kabul, and lost 15,000 men to thirst and hunger, earning this force the epithet of the "Doomed Army".[41][42] Abd al-Rahman ibn Muhammad ibn al-Ash'ath led 20,000 troops each from Kufa and Basra[43] in a cautions but successful campaign in 700 AD, but when he wanted to stop during winter, Al-Hajjaj's insulting rebuke[44] led to mutiny.[45] The mutiny put down by 704 AD, and Al-Hajjaj granted a 7-year truce to Zunbil

Umayyad expansion in Sind and Multan

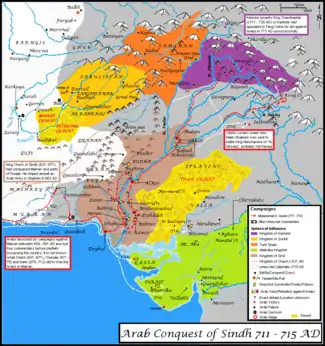

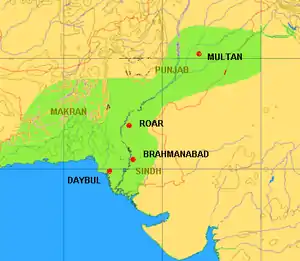

Raja Dahir of Sindh had refused to return Arab rebels from Sindh[13][46] and furthermore, Meds and others.[47] Meds shipping from their bases at Kutch, Debal and Kathiawar.[47] in one of their raids had kidnapped Muslim women travelling from Sri Lanka to Arabia, thus providing a casus belli[47][48] against Sindh Raja Dahir[49] when Raja Dahir expressed his inability to help retrieve the prisoners. After two expeditions were defeated in Sindh[50][51] Al Hajjaj equipped an army built around 6,000 Syrian cavalry and detachments of mawali from Iraq,[52] six thousand camel riders, and a baggage train of 3,000 camels under his Nephew Muhammad bin Qasim to Sindh. His Artillery of five catapults were sent to Debal by sea[52] ("manjaniks").

Conquest of Sindh

Muhammad bin Qasim departed from Shiraz in 710 CE, the army marched along the coast to Tiaz in Makran, then to the Kech valley. Muhammad re-subdued the restive towns of Fannazbur and Armabil, (Lasbela)[53] finally completing the conquest of Makran then the army met up with the reinforcements and catapults sent by sea near Debal and took Debal through assault.[52] From Debal the Arabs moved north along the Indus, clearing the region up to Budha, some towns like Nerun and Sadusan (Sehwan) surrendered peacefully[52] while tribes inhabiting Sisam were defeated in battle. Muhammad bin Qasim moved back to Nerun to resupply and receive reinforcements sent by Hajjaj.[52] The Arabs crossed the Indus further South and defeated the army of Dahir, who was killed.[54][55] The Arabs then marched north along the east bank of the Indus after the siege and capture of Rawer. Brahmanabad, then Alor (Aror) and finally Multan, were captured alongside other in-between towns with only light Muslim casualties.[52] Arabs marched up to the foothills of Kashmir along the Jhelum in 713 AD,[56] and the stormed on Al-Kiraj (probably the Kangra valley)[57] Muhammad was deposed after the death of Caliph Walid in 715 AD. Jai Singh, son of Dahir captured Brahmanabad and Arab rule was restricted to the Western shore of Indus.[58] Sindh was briefly lost to the caliph when the rebel Yazid b. Muhallab took over Sindh briefly in 720 AD.[59][60]

Last Umayyad campaigns in Al Hind

Junaid b. Abd Al Rahman Al Marri became the governor of Sindh in 723 AD. Secured Debal, then defeat and killed Jai Singh[59][61] secured Sindh and Southern Punjaband stormed Al Kiraj (Kangra valley) in 724 AD.[57][62] Junaid next attacked a number of Hindu kingdoms in what is now Rajasthan, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh aiming at permanent conquest, but the chronology and area of operation of the campaigns during 725 – 743 AD is difficult to follow because accurate, complete information is lacking.[57] The Arabs moved east from Sindh in several detachments[12] and probably from attacked from both the land and the sea, occupying Mirmad (Marumada, in Jaisalmer), Al-Mandal (perhaps Okhamandal in Gujarat) or Marwar,[63] and Dahnaj, not identified, al-Baylaman (Bhilmal) and Jurz (Gurjara country—north Gujarat and southern Rajasthan).[64] and attacking Barwas (Broach), sacking Vallabhi.[65] Gurjara king Siluka[66] repelled Arabs from "Stravani and Valla", probably the area North of Jaisalmer and Jodhpur, and the invasion of Malwa but were ultimately defeated by Bappa Rawal and Nagabhata I in 725 AD near Ujjain.[67] Arabs lost control over the newly conquered territories and Sindh due to Arab tribal infighting and Arab soldiers deserting the newly conquered territory[68] in 731 AD.

Al Hakam b. Awana Al Kalbi recovered Sindh, and in c733 AD, founded the garrison city of Al Mahfuza ("The Well Guarded") similar to Kufa, Basra and Wasit, on the eastern side of a lake near Brahmanabad.[57] Hakam next attempted to reclaim the conquests of Junaid in Al Hind. Arab records merely state that he was successful, Indian records at Navasari[69] details that Arab forces defeated "Kacchella, Saindhava, Saurashtra, Cavotaka, Maurya and Gurjara" kings. The city of Al Mansura ("The Victorious") was founded near Al Mahfuza to commemorate pacification of Sindh by Amr b. Muhammad in c738 AD.[57] Al Hakam next invaded the Deccan in 739 AD with the intention of permanent conquest, but was decisively defeated at Navsari by the viceroy Avanijanashraya Pulakeshin of the Chalukya Empire serving Vikramaditya II. Arab rule was restricted to the west of Thar desert.

Last days of Caliphate control

When the Abbasid Revolution overthrew the Umayyads in 750 AD after the Third Fitna, Sindh became independent and was captured by Musa b. K'ab al Tamimi in 752 AD.[70] Zunbil had defeated the Arabs in 728 AD, and saw off two Abbasid invasions in 769 and 785 AD. Abbasids attacked Kabul several times and collected tribute between 787 AD – 815 AD and extracted tribute after each campaign. Abbasid Governor of Sindh, Hisham (7 in office 768 – 773 AD) raided Kashmir, recaptured parts of Punjab from Karkota control,[71] and launched naval raids against ports of Gujarat in 758 and 770 AD,[72] which like other Abbasid Naval raids launched of 776 and 779 AD, gained no territory. Arabs occupied Sindian (Southern Kutch) in 810 AD, only to lose it in 841 AD.[73] Civil war erupted in Sindh in 842 AD, and the Habbari dynasty occupied Mansurah, and by 871, five independent principalities emerged, with the Banu Habbari clan controlling in Mansurah, Banu Munabbih occupying Multan, Banu Madan ruling in Makran, with Makshey and Turan falling to other rulers, all outside direct Caliphate control.[74] Ismaili missionaries found a receptive audience among both the Sunni and non-Muslim populations in Multan, which became a center of the Ismaili sect of Islam. The Saffarid Dynasty of Zaranj occupied Kabul and the kingdom of Zunbil permanently in 871 AD. A new chapter of Muslim conquests began when the Samanid Dynasty took over the Saffarid Kingdom and Sabuktigin seized Ghazni.

Later Muslim invasions

Muslim incursions resumed under later Turkic and Central Asian dynasties like Saffarid Dynasty and Samanid Dynasty with more local capitals, who supplanted the Caliphate and expanded their domains both northwards and eastwards. Continues raids from these empires in north-west of India led to the loss of stability in the Indian kingdoms and led to establishment of Islam in the heart of India.

Ghaznavid Empire

.PNG.webp)

Under Sabuktigin, Ghaznavid Empire found itself in conflict with the Kabul Shahi Raja Jayapala in the east. When Sabuktigin died and his son Mahmud ascended the throne in 998, Ghazni was engaged in the North with the Qarakhanids when the Shahi Raja renewed hostilities in east once again.

In the early 11th century, Mahmud of Ghazni launched seventeen expeditions into Indian subcontinent. In 1001, Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni defeated Raja Jayapala of the Hindu Shahi Dynasty of Gandhara (in modern Afghanistan), in the Battle of Peshawar and marched further west of Peshawar (in modern Pakistan) and, in 1005, made it the center for his forces.

Writing c. 1030, Al Biruni reported on the devastation caused during the conquest of Gandhara and much of northwest India by Mahmud of Ghazni following his defeat of Jayapala in the Battle of Peshawar at Peshawar in 1001:

Now in the following times no Muslim conqueror passed beyond the frontier of Kabul and the river Sindh until the days of the Turks, when they seized the power in Ghazna under the Sâmânî dynasty, and the supreme power fell to the lot of Nasir-addaula Sabuktagin. This prince chose the holy war as his calling, and therefore called himself al-Ghazi ("the warrior/invader"). In the interest of his successors he constructed, in order to weaken the Indian frontier, those roads on which afterwards his son Yamin-addaula Mahmud marched into India during a period of thirty years and more. God be merciful to both father and son! Mahmud utterly ruined the prosperity of the country, and performed there wonderful exploits, by which the Hindus became like atoms of dust scattered in all directions, and like a tale of old in the mouth of the people. Their scattered remains cherish, of course, the most inveterate aversion towards all Muslims. This is the reason, too, why Hindu sciences have retired far away from those parts of the country conquered by us, and have fled to places which our hand cannot yet reach, to Kashmir, Benares, and other places. And there the antagonism between them and all foreigners receives more and more nourishment both from political and religious sources.[75]

During the closing years of the tenth and the early years of the succeeding century of our era, Mahmud the first Sultan and Musalman of the Turk dynasty of kings who ruled at Ghazni, made a succession of inroads twelve or fourteen in number, into Gandhar – the present Peshwar valley – in the course of his proselytizing invasions of Hindustan.[76]

Fire and sword, havoc and destruction, marked his course everywhere. Gandhar which was styled the Garden of the North was left at his death a weird and desolate waste. Its rich fields and fruitful gardens, together with the canal which watered them (the course of which is still partially traceable in the western part of the plain), had all disappeared. Its numerous stone built cities, monasteries, and topes with their valuable and revered monuments and sculptures, were sacked, fired, razed to the ground, and utterly destroyed as habitations.[76]

The Ghaznavid conquests were initially directed against the Ismaili Fatimids of Multan, who were engaged in an ongoing struggle with the provinces of the Abbasid Caliphate in conjunction with their compatriots of the Fatimid Caliphate in North Africa and the Middle East; Mahmud apparently hoped to curry the favor of the Abbasids in this fashion. However, once this aim was accomplished, he moved onto the richness of the loot of Indian temples and monasteries. By 1027, Mahmud had captured parts of North India and obtained formal recognition of Ghazni's sovereignty from the Abbassid Caliph, al-Qadir Billah.

Ghaznavid rule in Northwestern India (modern Afghanistan and Pakistan) lasted over 175 years, from 1010 to 1187. It was during this period that Lahore assumed considerable importance apart from being the second capital, and later the only capital, of the Ghaznavid Empire.

At the end of his reign, Mahmud's empire extended from Kurdistan in the west to Samarkand in the Northeast, and from the Caspian Sea to the Punjab in the west. Although his raids carried his forces across Northern and Western India, only Punjab came under his permanent rule; Kashmir, the Doab, Rajasthan, and Gujarat remained nominal under the control of the local Indian dynasties. In 1030, Mahmud fell gravely ill and died at age 59. As with the invaders of three centuries ago, Mahmud's armies reached temples in Varanasi, Mathura, Ujjain, Maheshwar, Jwalamukhi, Somnath and Dwarka.

Ghurid Empire

Mu'izz al-Din better known as Shahāb-ud-Din Muhammad Ghori was a conqueror from the region of Ghor in modern Afghanistan. Before 1160, the Ghaznavid Empire covered an area running from central Iran east to the Punjab, with capitals at Ghazni on the banks of Ghazni river in present-day Afghanistan, and at Lahore in present-day Pakistan. In 1160, the Ghurids conquered Ghazni from the Ghaznavids, and in 1173 Muhammad Bin Sām was made governor of Ghazni. In 1186 and 1187 he conquered Lahore in alliance with a local Hindu ruler, ending the Ghaznavid empire and bringing the last of Ghaznavid territory under his control, and seemed to be the first Muslim ruler seriously interested in expanding his domain in the sub-continent, and like his predecessor Mahmud initially started off against the Ismaili kingdom of Multan that had regained independence during the Nizari conflicts, and then onto booty and power.

In 1191, he invaded the territory of Prithviraj III of Ajmer, who ruled his territory from Delhi to Ajmer in present-day Rajasthan, but was defeated at the First Battle of Tarain.[77] The following year, Mu'izz al-Din assembled 120,000 horsemen and once again invaded India. Mu'izz al-Din's army met Prithviraj's army again at Tarain, and this time Mu'izz al-Din won; Govindraj was slain, Prithviraj executed[78] and Mu'izz al-Din advanced onto Delhi. Within a year, Mu'izz al-Din controlled North-Western Rajasthan and Northern Ganges-Yamuna Doab. After these victories in India, and Mu'izz al-Din's establishment Delhi as the capital of his Indian provinces, Multan was also incorporated as a major part of his empire. Mu'izz al-Din then returned east to Ghazni to deal with the threat on his eastern frontiers from the Turks of the Khwarizmian Empire, whiles his armies continued to advance through Northern India, raiding as far as Bengal.

Mu'izz al-Din returned to Lahore after 1200. In 1206, Mu'izz al-Din had to travel to Lahore to crush a revolt. On his way back to Ghazni, his caravan rested at Damik near Sohawa (which is near the city of Jhelum in the Punjab province of modern-day Pakistan). He was assassinated on 15 March 1206, while offering his evening prayers. The identity of Ghori's assassins is disputed, with some claiming that he was assassinated by local Hindu Gakhars and others claiming he was assassinated by Hindu Khokhars, both being different tribes.

The Khokhars were killed in large numbers, and the province was pacified. After settling the affairs in the Punjab. Mu'izz al-Din marched back to Ghazni. While camping at Dhamayak in 1206 AD in the Jehlum district, the sultan was murdered by the Khokhars[79]

Some claim that Mu'izz al-Din was assassinated by the Hashshashin, a radical Ismaili Muslim sect.[80][81]

According to his wishes, Mu'izz al-Din was buried where he fell, in Damik. Upon his death his most capable general, Qutb-ud-din Aybak, took control of Mu'izz al-Din's Indian provinces and declared himself the first Sultan of Delhi Sultanate.

Delhi Sultanate

Muhammad's successors established the first dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate, while the Mamluk Dynasty in 1211 (however, the Delhi Sultanate is traditionally held to have been founded in 1206) seized the reins of the empire. Mamluk means "slave" and referred to the Turkic slave soldiers who became rulers. The territory under control of the Muslim rulers in Delhi expanded rapidly. By mid-century, Bengal and much of central India was under the Delhi Sultanate. Several Turko-Afghan dynasties ruled from Delhi: the Mamluk (1206–1290), the Khalji (1290–1320), the Tughlaq (1320–1414), the Sayyid (1414–51), and the Lodhi (1451–1526). During the time of Delhi Sultanate, the Vijayanagara Empire resisted successfully attempts of Delhi Sultanate to establish dominion in the Southern India, serving as a barrier against invasion by the Muslims.[83] Certain kingdoms remained independent of Delhi such as the larger kingdoms of Punjab, Rajasthan, parts of the Deccan, Gujarat, Malwa (central India), and Bengal, nevertheless all of the area in present-day Pakistan came under the rule of Delhi.

The Sultans of Delhi enjoyed cordial, if superficial, relations with Muslim rulers in the Near East but owed them no allegiance. They based their laws on the Quran and the sharia and permitted non-Muslim subjects to practice their religion only if they paid the jizya (poll tax). They ruled from urban centres, while military camps and trading posts provided the nuclei for towns that sprang up in the countryside.

Perhaps the most significant contribution of the Sultanate was its temporary success in insulating the subcontinent from the potential devastation of the Mongol invasion from Central Asia in the 13th century, which nonetheless led to the capture of Afghanistan and western Pakistan by the Mongols (see the Ilkhanate Dynasty). Under the Sultanate, "Indo-Muslim" fusion left lasting monuments in architecture, music, literature, and religion. In addition it is surmised that the language of Urdu (literally meaning "horde" or "camp" in various Turkic dialects) was born during the Delhi Sultanate period as a result of the mingling of Sanskritic Hindi and the Persian, Turkish, Arabic favoured by the Muslim invaders of India.

The Sultanate suffered significantly from the sacking of Delhi in 1398 by Timur, but revived briefly under the Lodi Dynasty, the final dynasty of the Sultanate before it was conquered by Zahiruddin Babur in 1526, who subsequently founded the Mughal Dynasty that ruled from the 16th to the 18th centuries.

Timur

Tīmūr bin Taraghay Barlas, known in the West as Tamerlane or "Timur the lame", was a 14th-century warlord of Turco-Mongol descent,[85][86][87][88] conqueror of much of western and central Asia, and founder of the Timurid Empire (1370–1507) in Central Asia; the Timurid dynasty survived until 1857 as the Mughal dynasty of India.

Informed about civil war in South Asia, Timur began a trek starting in 1398 to invade the reigning Sultan Nasir-u Din Mehmud of the Tughlaq Dynasty in the north Indian city of Delhi.[89] His campaign was politically pretexted that the Muslim Delhi Sultanate was too tolerant toward its "Hindu" subjects, but that could not mask the real reason being to amass the wealth of the Delhi Sultanate.[90]

Timur crossed the Indus River at Attock (now Pakistan) on 24 September. In Haryana, his soldiers each killed 50 to 100 Hindus.[91]

Timur's invasion did not go unopposed and he did meet some resistance during his march to Delhi, most notably with the Sarv Khap coalition in northern India, and the Governor of Meerut. Although impressed and momentarily stalled by the valour of Ilyaas Awan, Timur was able to continue his relentless approach to Delhi, arriving in 1398 to combat the armies of Sultan Mehmud, already weakened by an internal battle for ascension within the royal family.

The Sultan's army was easily defeated on 17 December 1398. Timur entered Delhi and the city was sacked, destroyed, and left in ruins. Before the battle for Delhi, Timur executed more than 100,000 "Hindu" captives.[85][89]

Timur himself recorded the invasions in his memoirs, collectively known as Tuzk-i-Timuri.[85][89][92][93] Timur's purported autobiography, the Tuzk-e-Taimuri ("Memoirs of Temur") is a later fabrication, although most of the historical facts are accurate.[94]

Muslim historian Irfan Habib writes in "Timur in the Political Tradition and Historiography of Mughal India" that in the 14th century, the word "Hindu" (people of "Al-Hind", "Hind" being "India") included "both Hindus and Muslims" in religious connotations.[95]

When Timur entered Delhi after defeating Mahmud Toghloq's forces, he granted an amnesty in return for protection money (mâl-e amâni). But on the fourth day he ordered that all the people of the city be enslaved; and so they were. Thus reports Yahya, who here inserts a pious prayer in Arabic for the victims' consolation ("To God we return, and everything happens by His will"). Yazdi, on the other hand, does not have any sympathy to waste on these wretches. He records that Timur had granted protection to the people of Delhi on 18 December 1398, and the collectors had begun collecting the protection money. But large groups of Timur's soldiers began to enter the city and, like birds of prey, attacked its citizens. The "pagan Hindus" (Henduân-e gabr) having had the temerity to begin immolating their women and themselves, the three cities of Delhi were put to sack by Timur's soldiers. "Faithless Hindus", he adds, had gathered in the Congregation Mosque of Old Delhi and Timur's officers put them ruthlessly to slaughter there on 29 December. Clearly, Yazdi's "Hindus" included Muslims as well.[96]

However, that does not prove that the men gathering at the mosque were Muslims as it could have been Hindus who gathered at the Mosque for protection.

The statement implying that Muslims were targeted during the Delhi massacre was contradicted by Timur's own words, during the 15-day massacre of Delhi, Timur himself stated that "Excepting the quarters of the sayyids, the 'ulama and the other Musalmans (Muslims), the whole city was sacked", proving that Timur differentiated between the two religious groups (Muslims and Hindus).[97]

During the mass murder of Delhi, Timur's soldiers massacred more than 150,000 Indians, and all inhabitants not killed were captured and enslaved.

Timur's memoirs on his invasion of India describe in detail the massacre of "Hindus", looting plundering and raping of their women and the plunder of the wealth of Hindustan (Greater India). It gives details of how villages, towns and entire cities were rid of their "Hindu" male population through systematic mass slaughters and genocide.

Timur left Delhi in approximately January 1399. In April he had returned to his own capital beyond the Oxus (Amu Darya). Immense quantities of spoils were taken from India. According to Ruy Gonzáles de Clavijo, 90 captured elephants were employed merely to carry precious stones looted from his conquest, so as to erect a mosque at Samarkand – what historians today believe is the enormous Bibi-Khanym Mosque. Ironically, the mosque was constructed too quickly and suffered greatly from disrepair within a few decades of its construction.

Regional sultanates

Kashmir was conquered by the Shah Mir dynasty in the 14th century. Regional kingdoms such as Bengal, Gujarat, Malwa, Khandesh, Jaunpur, and Bahmanis expanded at the expense of the Delhi Sultanate. Gaining conversions to Islam was easier under regional Sultanates.[98]

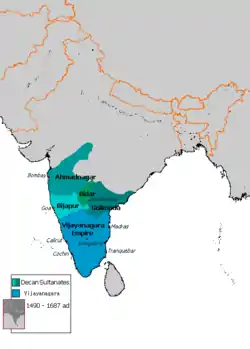

Deccan Sultanates

The term of Deccan Sultanates[99] was used for five Muslim dynasties that ruled several late medieval Indian kingdoms, namely Bijapur Sultanate,[100] Golkonda Sultanate,[101] Ahmadnagar Sultanate,[102] Bidar Sultanate,[103] and Berar Sultanate[104] in South India. The Deccan Sultanates ruled the Deccan Plateau between the Krishna River and the Vindhya Range. These sultanates became independent during the break-up of the Bahmani Sultanate, another Muslim empire.[105]

The ruling families of all these five sultanates were of diverse origin; the Qutb Shahi dynasty of Golconda Sultanate was of Turkmen origin,[106] the Barid Shahi dynasty of Bidar Sultanate being founded by a Turkic noble,[107] the Adil Shahi dynasty of Bijapur Sultanate was founded by a Georgian-Oghuz Turkic slave[108] while Nizam Shahi dynasty of Ahmadnagar Sultanate and Imad Shahi dynasty of Berar Sultanate were of Hindu lineage[109] (Ahmadnagar being Brahmin[109] and Berar being Kanarese[109]).

Mughal Empire

India in the early 16th century presented a fragmented picture of rulers who lacked concern for their subjects and failed to create a common body of laws or institutions. Outside developments also played a role in shaping events. The circumnavigation of Africa by the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama in 1498 allowed Europeans to challenge Muslim control of the trading routes between Europe and Asia. In Central Asia and Afghanistan, shifts in power pushed Babur of the Timurid Dynasty (in present-day Uzbekistan) southward, first to Kabul and then to the heart of Indian subcontinent. The dynasty he founded endured for more than three centuries.

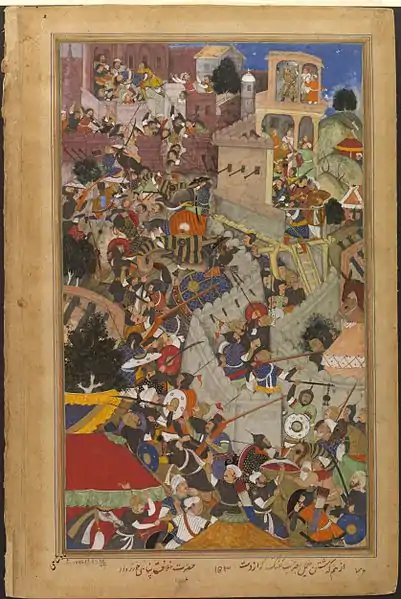

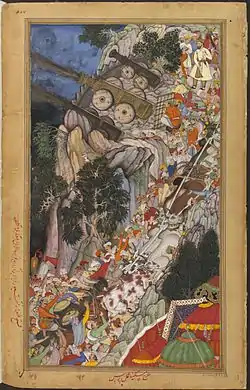

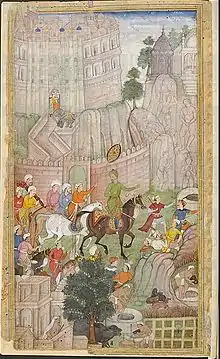

The Mughal Emperor Akbar shoots the Rajput warrior Jaimal during the Siege of Chittorgarh in 1567.

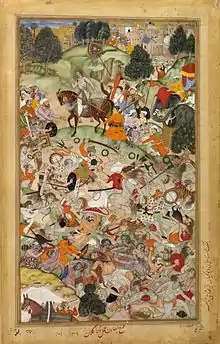

The Mughal Emperor Akbar shoots the Rajput warrior Jaimal during the Siege of Chittorgarh in 1567. Bullocks dragging siege-guns up hill during Mughal Emperor Akbar's attack on Ranthambhor Fort in 1568.

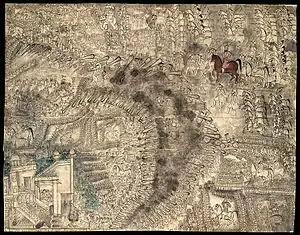

Bullocks dragging siege-guns up hill during Mughal Emperor Akbar's attack on Ranthambhor Fort in 1568.

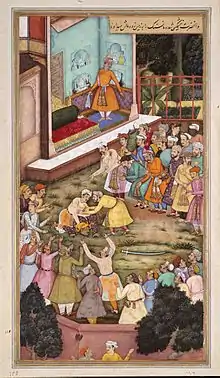

Rajput women committing Jauhar during Akbar's invasion.

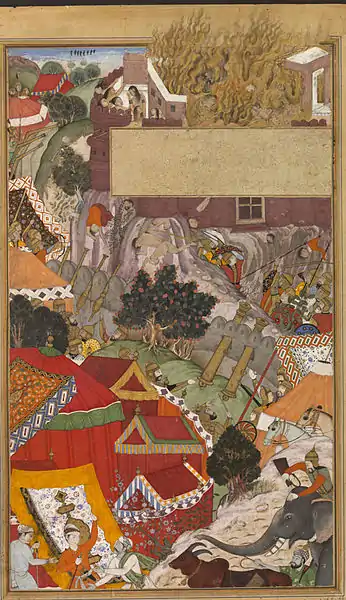

Rajput women committing Jauhar during Akbar's invasion. A War elephant executing the opponents of the Emperor Akbar.

A War elephant executing the opponents of the Emperor Akbar.

Babur

A descendant of both Genghis Khan and Timur the Great, Babur combined strength and courage with a love of beauty, and military ability with cultivation. He concentrated on gaining control of Northwestern India, doing so in 1526 by defeating the last Lodhi Sultan at the First battle of Panipat, a town north of Delhi. Babur then turned to the tasks of persuading his Central Asian followers to stay on in India and of overcoming other contenders for power, like the Rajputs and the Afghans. He succeeded in both tasks but died shortly thereafter in 1530. The Mughal Empire was one of the largest centralised states in premodern history and was the precursor to the British Indian Empire.

Babur was followed by his great-grandson, Shah Jahan (r. 1628–58), builder of the Taj Mahal and other magnificent buildings. Two other towering figures of the Mughal era were Akbar (r. 1556–1605) and Aurangzeb (r. 1658–1707). Both rulers expanded the empire greatly and were able administrators. However, Akbar was known for his religious tolerance and administrative genius while Aurangzeb was a pious Muslim and fierce advocate of more orthodox Islam.

Aurangzeb

While some rulers were zealous in their spread of Islam, others were relatively liberal. The Mughal emperor Akbar, an example of the latter established a new religion, Din E Elahi, which included beliefs from different faiths and even build many temples in his empire. He abolished the jizya twice. In contrast, his great-grandson Aurangazeb was a more religious and orthodox ruler.

In the century-and-a-half that followed the death of Aurangzeb, effective Muslim control started weakening. Succession to imperial and even provincial power, which had often become hereditary, was subject to intrigue and force. The mansabdari system gave way to the zamindari system, in which high-ranking officials took on the appearance of hereditary landed aristocracy with powers of collecting rents. As Delhi's control waned, other contenders for power emerged and clashed, thus preparing the way for the eventual British takeover.

Durrani Empire

Ahmed Shah Abdali – a Pashtun – embarked on a conquest in South Asia starting in 1747.[112] In the short space of just over a quarter of a century, he forged one of the largest Muslim empires of the 18th century after the Ottomans and Qajars of Iran. The high point of his conquests was his victory over the powerful Marathas in the third Battle of Panipat 1761. In the Indian subcontinent, his empire stretched from the Indus at Attock all the way to the eastern Punjab. Uninterested in long-term of conquest or in replacing the Mughal Empire, he became increasingly pre occupied with revolts by the Sikhs.[113] Vadda Ghalughara took place under the Muslim provincial government based at Lahore to wipe out the Sikhs, with 30,000 Sikhs being killed, an offensive that had begun with the Mughals, with the Chhota Ghallughara,[114] and lasted several decades under its Muslim successor states. His empire started to unravel not longer than a few decades after his death.

Decline of Muslim rule in Indian subcontinent

Maratha Empire

There is no doubt that the single most important power to emerge in the long twilight of the Mughal dynasty was the Maratha Confederacy (1674 CE – 1818 CE).[116] The Marathas are responsible, to a large extent, for ending Mughal rule in India.[117] The Maratha Empire ruled large parts of India following the decline of the Mughals. The long and futile war bankrupted one of the most powerful empires in the world. Mountstart Elphinstone termed this a demoralizing period for the Muslims as many of them lost the will to fight against the Maratha Empire.[118][119][120] Maratha empire at its peak stretched from Tamil Nadu (Trichinopoly) "present Tiruchirappalli" in the south to the Afghan border in the north.[121][122][123] In early 1771, Mahadji, a notable Maratha general, recaptured Delhi and installed Shah Alam II as the puppet ruler on the Mughal throne. In north India, the Marathas thus regained the territory and the prestige lost as result of the defeat at Panipath in 1761.[124] However regions of Kashmir, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Western Punjab, were captured by Marathas between 1758 and 1759, remained in Afghan rule before ascension of Sikh power.[125] Mahadji ruled the Punjab as it used to be a Mughal territory and Sikh sardars and other Rajas of the cis-Sutlej region paid tributes to him.[126] A considerable portion of the Indian subcontinent came under the sway of the British Empire after the Third Anglo-Maratha War, which ended the Maratha Empire in 1818.

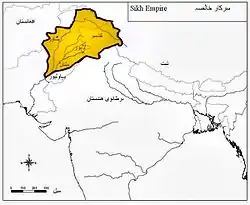

Sikh Empire

In northwest India, in the Punjab, Sikhs developed themselves into a powerful force under the authority of twelve Misls. By 1801, Ranjit Singh captured Lahore and threw off the Afghan yoke from North West India.[127] In Afghanistan Zaman Shah Durrani was defeated by powerful Barakzai chief Fateh Khan who appointed Mahmud Shah Durrani as the new ruler of Afghanistan and appointed himself as Wazir of Afghanistan.[128] Sikhs however were now superior to the Afghans and started to annex Afghan provinces. The biggest victory of the Sikh Empire over the Durrani Empire came in the Battle of Attock fought in 1813 between Sikh and Wazir of Afghanistan Fateh Khan and his younger brother Dost Mohammad Khan. The Afghans were routed by the Sikh army and the Afghans lost over 9,000 soldiers in this battle. Dost Mohammad was seriously injured whereas his brother Wazir Fateh Khan fled back to Kabul fearing that his brother was dead.[129] In 1818 they slaughtered Afghans and Muslims in trading city of Multan killing Afghan governor Nawab Muzzafar Khan and five of his sons in the Siege of Multan.[130] In 1819 the last Indian Province of Kashmir was conquered by Sikhs who registered another crushing victory over weak Afghan General Jabbar Khan.[131] The Koh-i-Noor diamond was also taken by Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1814. In 1823 a Sikh Army routed Dost Mohammad Khan the Sultan of Afghanistan and his brother Azim Khan at Naushera (Near Peshawar). By 1834 the Sikh Empire extended up to the Khyber Pass. Hari Singh Nalwa the Sikh general remained the governor of Khyber Agency till his death in 1837. He consolidated Sikh hold in tribal provinces. The northernmost Indian territories of Gilgit, Baltistan and Ladakh was annexed between 1831 and 1840.[132]

Impact on India, Islam and Muslims in India

Historian Will Durant wrote about medieval India, "The Islamic conquest of India is probably the bloodiest story in history. It is a discouraging tale, for its evident moral is that civilization is a precious good, whose delicate complex of order and freedom, culture and peace, can at any moment be overthrown by barbarians invading from without or multiplying within."[133]

Conversion theories

Considerable controversy exists both in scholarly and public opinion as to how conversion to Islam came about in Indian subcontinent, typically represented by the following schools of thought:[134]

- Conversion was a combination, initially by violence, threat or other pressure against the person.[134]

- As a socio-cultural process of diffusion and integration over an extended period of time into the sphere of the dominant Muslim civilization and global polity at large.[135]

- That conversions occurred for non-religious reasons of pragmatism and patronage such as social mobility among the Muslim ruling elite[134][135]

- That the bulk of Muslims are descendants of migrants from the Iranian plateau or Arabs.[135]

- Conversion was a result of the actions of Sufi saints and involved a genuine change of heart.[134]

Hindus who converted to Islam however were not completely immune to persecution due to the caste system among Muslims in India established by Ziauddin al-Barani in the Fatawa-i Jahandari,[136] where they were regarded as an "Ajlaf" caste and subjected to discrimination by the "Ashraf" castes.[137] Critics of the "religion of the sword theory" point to the presence of the strong Muslim communities found in Southern India, modern day Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, western Burma, Indonesia and the Philippines coupled with the distinctive lack of equivalent Muslim communities around the heartland of historical Muslim empires in South Asia as refutation to the "conversion by the sword theory".[135] The legacy of Muslim conquest of South Asia is a hotly debated issue even today. Not all Muslim invaders were simply raiders. Later rulers fought on to win kingdoms and stayed to create new ruling dynasties. The practices of these new rulers and their subsequent heirs (some of whom were born of Hindu wives of Muslim rulers) varied considerably. While some were uniformly hated, others developed a popular following. According to the memoirs of Ibn Battuta who traveled through Delhi in the 14th century, one of the previous sultans had been especially brutal and was deeply hated by Delhi's population. His memoirs also indicate that Muslims from the Arab world, Persia and Turkey were often favored with important posts at the royal courts suggesting that locals may have played a somewhat subordinate role in the Delhi administration. The term "Turk" was commonly used to refer to their higher social status. However S.A.A. Rizvi[138] points to Muhammad bin Tughlaq as not only encouraging locals but promoting artisan groups such as cooks, barbers and gardeners to high administrative posts. In his reign, it is likely that conversions to Islam took place as a means of seeking greater social mobility and improved social standing.[139]

Aurangzeb

Aurangzeb's Deccan campaign saw one of the largest death tolls in South Asian history, with an estimated 4.6 million people killed during his reign, Muslims and Hindus alike.[140] An estimated of 2.5 million of Aurangzeb's army were killed during the Mughal–Maratha Wars (100,000 annually during a quarter-century), while 2 million civilians in war-torn lands died due to drought, plague and famine.[141][140]

Expansion of trade

Islam's impact was the most notable in the expansion of trade. The first contact of Muslims with India was the Arab attack on a nest of pirates near modern-day Mumbai to safeguard their trade in the Arabian Sea. Around the same time many Arabs settled at Indian ports, giving rise to small Muslim communities. The growth of these communities was not only due to conversion but also the fact that many Hindu kings of south India (such as those from Cholas) hired Muslims as mercenaries.[142]

A significant aspect of the Muslim period in world history was the emergence of Islamic Sharia courts capable of imposing a common commercial and legal system that extended from Morocco in the West to Mongolia in the North East and Indonesia in the South East. While southern India was already in trade with Arabs/Muslims, northern India found new opportunities. As the Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms of Asia were subjugated by Islam, and as Islam spread through Africa – it became a highly centralising force that facilitated in the creation of a common legal system that allowed letters of credit issued in say Egypt or Tunisia to be honoured in India or Indonesia (The Sharia has laws on the transaction of business with both Muslims and non-Muslims). In order to cement their rule, Muslim rulers initially promoted a system in which there was a revolving door between the clergy, the administrative nobility and the mercantile classes. The travels of explorer Muhammad Ibn-Abdullah Ibn-Batuta were eased because of this system. He served as an Imam in Delhi, as a judicial official in the Maldives, and as an envoy and trader in the Malabar. There was never a contradiction in any of his positions because each of these roles complemented the other. Islam created a compact under which political power, law and religion became fused in a manner so as to safeguard the interests of the mercantile class. This led world trade to expand to the maximum extent possible in the medieval world. Sher Shah Suri took initiatives in improvement of trade by abolishing all taxes which hindered progress of free trade. He built large networks of roads and constructed Grand Trunk Road (1540–1544), which connects Chittagong to Kabul. Parts of it are still in use today. The geographic regions add to the diversity of languages and politics.

Cultural influence

The divide and rule policies, two-nation theory, and subsequent partition of India in the wake of Independence from the British Empire has polarised the sub-continental psyche, making objective assessment hard in comparison to the other settled agricultural societies of India from the North West. Muslim rule differed from these others in the level of assimilation and syncretism that occurred. They retained their identity and introduced legal and administrative systems that superseded existing systems of social conduct and ethics. While this was a source of friction it resulted in a unique experience the legacy of which is a Muslim community strongly Islamic in character while at the same time distinctive and unique among its peers.

The impact of Islam on Indian culture has been inestimable. It permanently influenced the development of all areas of human endeavour – language, dress, cuisine, all the art forms, architecture and urban design, and social customs and values. Conversely, the languages of the Muslim invaders were modified by contact with local languages, to Urdu, which uses the Arabic script. This language was also known as Hindustani, an umbrella term used for the vernacular terminology of Hindi as well as Urdu, both major languages in South Asia today derived primarily from Sanskrit grammatical structures and vocabulary.

Muslim rule saw a greater urbanisation of India and the rise of many cities and their urban cultures. The biggest impact was upon trade resulting from a common commercial and legal system extending from Morocco to Indonesia. This change of emphasis on mercantilism and trade from the more strongly centralised governance systems further clashed with the agricultural based traditional economy and also provided fuel for social and political tensions.

A related development to the shifting economic conditions was the establishment of Karkhanas, or small factories and the import and dissemination of technology through India and the rest of the world. The use of ceramic tiles was adopted from architectural traditions of Iraq, Iran, and Central Asia. Rajasthan's blue pottery was a local variation of imported Chinese pottery. There is also the example of Sultan Abidin (1420–70) sending Kashmiri artisans to Samarqand to learn book-binding and paper making. Khurja and Siwan became renowned for pottery, Moradabad for brass ware, Mirzapur for carpets, Firozabad for glass wares, Farrukhabad for printing, Sahranpur and Nagina for wood-carving, Bidar and Lucknow for bidriware, Srinagar for papier-mache, Benaras for jewellery and textiles, and so on. On the flip-side encouraging such growth also resulted in higher taxes on the peasantry.

Numerous Indian scientific and mathematical advances and the Hindu numerals were spread to the rest of the world and much of the scholarly work and advances in the sciences of the age under Muslim nations across the globe were imported by the liberal patronage of Arts and Sciences by the rulers. The languages brought by Islam were modified by contact with local languages leading to the creation of several new languages, such as Urdu, which uses the modified Arabic script, but with more Persian words. The influences of these languages exist in several dialects in India today.

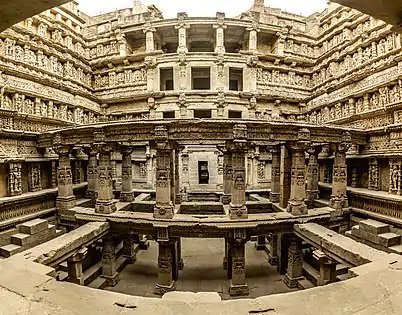

Islamic and Mughal architecture and art is widely noticeable in India, examples being the Taj Mahal and Jama Masjid. At the same time, Muslim rulers destroyed many of the ancient Indian architectural marvels and converted them into Islamic structures, most notably at Varanasi, Mathura, Ayodhya and the Kutub Complex in New Delhi.

Migration of Hindus

Few groups of Hindus including Rajputs were entering what is today Nepal before the fall of Chittor due to regular invasions of Muslims in India.[143] After the fall of Chittorgarh in 1303 by the Alauddin Khilji of the Khalji dynasty, Rajputs from the region immigrated in large groups into what is today Nepal due to heavy religious persecution. The incident is supported by both the Rajput and Nepalese traditions.[144][145][146][143][note 1] Indian scholar Rahul Ram asserts that the Rajput immigration into what is today Nepal is an undoubted fact but there can be questions in purity of blood of some leading families.[149] Historian James Todd mentions that there was a one Rajasthani tradition that mentions the immigration of Rajputs from Mewar to Himalayas in the late 12th century after the battle between Chittor and Muhammad Ghori.[150] Historian John T Hitchcock and John Whelpton contends that the regular invasions by Muslims led to heavy influx of Rajputs with Brahmins from the 12th century.[151][152]

The entry of Rajputs in central region of what is today Nepal were easily assisted by Khas Malla rulers who had developed a large feudatory state covering more than half of the Greater Nepal.[143] The Hindu immigrants including Rajputs were mixed into the Khas society quickly as a result of much resemblance.[143] Also, the Magar tribesmen of the Western region of what is today Nepal welcomed the immigrant Rajput chiefs with much cordiality.[153]

Iconoclasm

Iconoclasm under the Delhi Sultanate

Historian Richard Eaton has tabulated a campaign of destruction of idols and temples by Delhi Sultans, intermixed with instances of years where the temples were protected from desecration.[154][156][157] In his paper, he has listed 37 instances of Hindu temples being desecrated or destroyed in India during the Delhi Sultanate, from 1234 to 1518, for which reasonable evidences are available.[158][159][160] He notes that this was not unusual in medieval India, as there were numerous recorded instances of temple desecration by Hindu and Buddhist kings against rival Indian kingdoms between 642 and 1520, involving conflict between devotees of different Hindu deities, as well as between Hindus, Buddhists and Jains.[154][161][162] He also noted there were also many instances of Delhi sultans, who often had Hindu ministers, ordering the protection, maintenance and repairing of temples, according to both Muslim and Hindu sources. For example, a Sanskrit inscription notes that Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq repaired a Siva temple in Bidar after his Deccan conquest. There was often a pattern of Delhi sultans plundering or damaging temples during conquest, and then patronizing or repairing temples after conquest. This pattern came to an end with the Mughal Empire, where Akbar the Great's chief minister Abu'l-Fazl criticized the excesses of earlier sultans such as Mahmud of Ghazni.[158]

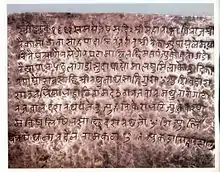

In many cases, the demolished remains, rocks and broken statue pieces of temples destroyed by Delhi sultans were reused to build mosques and other buildings. For example, the Qutb complex in Delhi was built from stones of 27 demolished Hindu and Jain temples by some accounts.[163] Similarly, the Muslim mosque in Khanapur, Maharashtra was built from the looted parts and demolished remains of Hindu temples.[164] Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji destroyed Buddhist and Hindu libraries and their manuscripts at Nalanda and Odantapuri Universities in 1193 AD at the beginning of the Delhi Sultanate.[165][166]

The first historical record in this period of a campaign of destruction of temples and defacement of faces or heads of Hindu idols lasted from 1193 through 1194 in Rajasthan, Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh under the command of Ghuri. Under the Mamluks and Khaljis, the campaign of temple desecration expanded to Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and Maharashtra, and continued through the late 13th century.[154] The campaign extended to Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu under Malik Kafur and Ulugh Khan in the 14th century, and by the Bahmanis in the 15th century.[165] Orissa temples were destroyed in the 14th century under the Tughlaqs.

Beyond destruction and desecration, the sultans of the Delhi Sultanate in some cases had forbidden reconstruction of damaged Hindu, Jain and Buddhist temples, and they prohibited repairs of old temples or construction of any new temples.[167][168] In certain cases, the Sultanate would grant a permit for repairs and construction of temples if the patron or religious community paid jizya (fee, tax). For example, a proposal by the Chinese to repair Himalayan Buddhist temples destroyed by the Sultanate army was refused, on the grounds that such temple repairs were only allowed if the Chinese agreed to pay jizya tax to the treasury of the Sultanate.[169][170] In his memoirs, Firoz Shah Tughlaq describes how he destroyed temples and built mosques instead and killed those who dared build new temples.[171] Other historical records from wazirs, amirs and the court historians of various Sultans of the Delhi Sultanate describe the grandeur of idols and temples they witnessed in their campaigns and how these were destroyed and desecrated.[172]

Nalanda

In 1193, the Nalanda University complex was destroyed by Afghan Khalji-Ghilzai Muslims under Bakhtiyar Khalji; this event is seen as the final milestone in the decline of Buddhism in India. He also burned Nalanda's major Buddhist library and Vikramshila University,[173] as well as numerous Buddhist monasteries in India. When the Tibetan translator, Chag Lotsawa Dharmasvamin (Chag Lo-tsa-ba, 1197–1264), visited northern India in 1235, Nalanda was damaged, looted, and largely deserted, but still standing and functioning with seventy students.

Mahabodhi, Sompura, Vajrasan and other important monasteries were found to be untouched. The Ghuri ravages only afflicted those monasteries that lay in the direct of their advance and were fortified in the manner of defensive forts.

By the end of the 12th century, following the Muslim conquest of the Buddhist stronghold in Bihar, Buddhism, having already declined in the South, declined in the North as well because survivors retreated to Nepal, Sikkim and Tibet or escaped to the South of the Indian sub-continent.

Martand

The Martand Sun Temple was built by the third ruler of the Karkota Dynasty, Lalitaditya Muktapida, in the 8th century CE.[174] The temple was completely destroyed on the orders of the Muslim ruler Sikandar Butshikan in the early 15th century, with demolition lasting a year. He ruled from 1389 to 1413 and is remembered for his strenuous efforts to convert the Hindus of Kashmir to Islam. These efforts included the destruction of numerous old temples, such as Martand, prohibition of Hindu rites, rituals and festivals and even the wearing of clothes in the Hindu style. He is known as "Butcher of Kashmir" and among the most hated figures among Kashmiri Hindus.[175]

Vijayanagara

The city flourished between the 14th century and 16th century, during the height of the Vijayanagara Empire. During this time, it was often in conflict with the kingdoms which rose in the Northern Deccan, and which are often collectively termed the Deccan Sultanates. The Vijaynagara Empire successfully resisted Muslim invasions for centuries. But in 1565, the empire's armies suffered a massive and catastrophic defeat at the hands of an alliance of the Sultanates, and the capital was taken. The victorious armies then razed, depopulated and destroyed the city over several months. The empire continued its slow decline, but the original capital was not reoccupied or rebuilt.

Somnath

Around 1024 CE, during the reign of Bhima I, Mahmud of Ghazni raided Gujarat, and plundered the Somnath temple. According to an 1169 CE inscription, Bhima rebuilt the temple. This inscription does not mention any destruction caused by Mahmud, and states that the temple had "decayed due to time".[176] In 1299, Alauddin Khalji's army under the leadership of Ulugh Khan defeated Karandev II of the Vaghela dynasty, and sacked the Somnath temple.[176] The temple was rebuilt by Mahipala Deva, the Chudasama king of Saurashtra in 1308. It was repeatedly attacked in the later centuries, including by the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb.[177] In 1665, the temple, was once again ordered to be destroyed by Mughal emperor Aurangzeb.[178] In 1702, he ordered that if Hindus had revived worship there, it should be demolished completely.[179]

.jpg.webp)

See also

- Decline of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent

- Bakhtiyar Khalji's Tibet campaign

- Mughal–Maratha Wars (1680–1707)

- Ahom–Mughal conflicts (1615–1682)

- Battle of Itakhuli (1682)

- Battle of Gujranwala (1761)

- List of early Hindu Muslim military conflicts in the Indian subcontinent

- Islamic conquest of Afghanistan

- List of Pashtun empires and dynasties

- Islamic empires in India

- Nader Shah's invasion of the Mughal Empire

- History of Pakistan

- History of Bangladesh

- Delhi Sultanate

- Mughal empire

- Mughal era

- Iconoclasm

- Persecution of Hindus

- Persecution of Buddhists

- Bodh Gaya bombings (2013)

- Buddhas of Bamyan (2001)

- Conversion of non-Islamic places of worship into mosques

Notes and references

Notes

- Scottish scholar Francis Buchanan-Hamilton doubts the first tradition of Rajput influx to what is today Nepal which states that Rajputs from Chittor came to Ridi Bazaar in 1495 A.D. and went on to capture the Gorkha Kingdom after staying in Bhirkot.[147] He mentions the second tradition which states that Rajputs reached Palpa through Rajpur at Gandak river.[144] The third tradition mentions that Rajputs reached Palpa through Kumaon and Jumla.[148]

Footnotes

- Heathcote 1995, p. 6.

- Anjum 2007, p. 234.

- Hermann Kulke and Dietmar Rothermund, A History of India, 3rd Edition, Routledge, 1998, ISBN 0-415-15482-0, pp 187-190

- Vincent A Smith, The Oxford History of India: From the Earliest Times to the End of 1911, p. 217, at Google Books, Chapter 2, Oxford University Press

- Jackson, Roy (2010). Mawlana Mawdudi and Political Islam: Authority and the Islamic State. Routledge. ISBN 9781136950360.

- Chapra, Muhammad Umer (2014). Morality and Justice in Islamic Economics and Finance. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 62–63. ISBN 9781783475728.

- "An Outline of the History of Persia During the Last Two Centuries (A.D. 1722–1922)". Edward G. Browne. London: Packard Humanities Institute. 1924. p. 33. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- Ian Copland; Ian Mabbett; Asim Roy; et al. (2012). A History of State and Religion in India. Routledge. p. 161.

- MacLean, Derryl N. (1989), Religion and Society in Arab Sind, pp. 126, BRILL, ISBN 90-04-08551-3

- S. A. A. Rizvi, "A socio-intellectual History of Isna Ashari Shi'is in India", Volo. 1, pp. 138, Mar'ifat Publishing House, Canberra (1986).

- S. A. N. Rezavi, "The Shia Muslims", in History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization, Vol. 2, Part. 2: "Religious Movements and Institutions in Medieval India", Chapter 13, Oxford University Press (2006).

- al-Balādhurī 1924, p. 209: "'Uthmân ibn-abu-l-'Âși ath-Thaķafi ... sent his brother, al-Hakam, to al-Bahrain, and went himself to 'Umân, and sent an army across to Tânah. When the army returned, he wrote to 'Umar, informing him of this expedition. 'Umar wrote to him in reply, ' ... By Allah, I swear that if they had been smitten, I would exact from thy tribe the equivalent.' Al-Hakam sent an expedition against Barwaș [Broach] also, and sent his brother, al-Mughîrah ibn-abu-l-'Âsi, to the gulf of ad-Daibul, where he met the enemy in battle and won a victory."

- Fredunbeg, Mirza Kalichbeg, "The Chachnama: An Ancient History of Sind", pp57

- Sen, Sailendra Nath, "Ancient Indian History and Civilization 2nd Edition", pp346

- Khushalani, Gobind, "Chachnama Retold An Account of the Arab Conquests of Sindh", pp221

- Editors: El Harier, Idris, & M'Baye, Ravene, "Spread of Islam Throughout the World ", pp594

- Mehta, Jaswant Lal, "Advanced Study in The History of Medieval India Vol 1", pp31

- Wink, Andre, " Al-Hind The Making of the Indo-Islamic Worlds Vol 1", pp119

- Wink, Andre, " Al-Hind The Making of the Indo-Islamic Worlds Vol 1", pp201

- Crawford, Peter, "The War of the Three Gods: Romans, Persians and the Rise of Islam", pp192

- Shaban M. A., "The Abbasid Revolution ", pp22 – pp23

- Editor = Daryaee, Touraj, "The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History", pp215 – pp216

- Elliot, Henry, "Historians of India: Appendix The Arabs in Sind, Vol III, Part 1", pp9

- Khushalani, Gobind, "Chachnama Retold An Account of the Arab Conquests of Sindh", pp72

- al-Balādhurī 1924, pp. 141–151

- Fredunbeg, Mirza Kalichbeg, "The Chachnama: An Ancient History of Sind", pp71 – pp79

- Hoyland, Robert G., "In Gods Path: The Arab Conquests and Creation of An Islamic Empire", pp191

- Wink, Andre, " Al-Hind The Making of the Indo-Islamic Worlds Vol 2", pp113

- Wink (2002), pg.129 – pp131

- Kennedy, Hugh, "The Great Arab Conquests", pp194 – pp196

- Dashti, Naseer, "The Baloch and Balochistan", pp65

- al-Balādhurī 1924, p. 212

- Dashti, Naseer, "The Baloch and Balochistan", pp78

- Khushalani, Gobind, "Chachnama Retold An Account of the Arab Conquests of Sindh", pp76

- al-Balādhurī 1924, p. 213

- Wink, Andre, " Al-Hind The Making of the Indo-Islamic Worlds Vol 1", pp128 – pp129

- al-Balādhurī 1924, p. 148: "Yazîd ibn-Ziyâd proceeded against them [the people of Kabul] and attacked them in Junzah, but he and many of those with him were killed, and the rest put to flight ... ransomed abu-'Ubaidah for 500,000 dirhams."

- al-Balādhurī 1924, p. 150

- Hoyland, Robert G., "In Gods Path: The Arab Conquests and Creation of An Islamic Empire", pp150

- Hitti, Philip, "History of The Arabs 10th Edition", pp209

- Kennedy, Hugh, "The Great Arab Conquests", pp196

- Hoyland, Robert G., "In Gods Path: The Arab Conquests and Creation of An Islamic Empire", pp152

- Kennedy, Hugh, "The Armies of The Caliph ", pp39

- Kennedy, Hugh, "The Prophet and The Age of The Caliphates", pp101

- Kennedy, Hugh, "The Great Arab Conquests", pp197 -pp198

- Editors: El Harier, Idris, & M'Baye, Ravene, "Spread of Islam Throughout the World ", pp604 – pp605

- Wink (2002), pg.164

- Nicholas F. Gier, FROM MONGOLS TO MUGHALS: RELIGIOUS VIOLENCE IN INDIA 9TH-18TH CENTURIES, Presented at the Pacific Northwest Regional Meeting American Academy of Religion, Gonzaga University, May, 2006

- Alexander Berzin, "Part I: The Umayyad Caliphate (661 – 750 CE), The First Muslim Incursion into the Indian Subcontinent", The Historical Interaction between the Buddhist and Islamic Cultures before the Mongol Empire Last accessed 21 June 2016

- al-Balādhurī 1924, p. 216

- Fredunbeg, Mirza Kalichbeg, "The Chachnama: An Ancient History of Sind", pp69

- Wink (2004) pg 201-205

- Wink (2004) pg 131

- Kennedy, Hugh, "The Great Arab Conquests", pp301

- Haig, Wolseley, "The Cambridge History of India, Vol III", pp5

- Fredunbeg, Mirza Kalichbeg, "The Chachnama: An Ancient History of Sind", pp176

- Blankinship, Khalid Y, "The End of Jihad State ", pp132

- al-Balādhurī 1924, p. 225: "Dâhir's son Hullishah, had come back to Brahmanâbâdh."

- al-Balādhurī 1924, p. 226: "Al-Junaid ibn'Abd-ar-Rahmân al-Murri governed the frontier of as-Sind for 'Umar ibn-Hubairah al-Fazâri."

- Blankinship, Khalid Y, "The End of Jihad State ", pp131

- Wink, Andre, " Al-Hind The Making of the Indo-Islamic Worlds Vol 1", pp208

- Misra, Shyam, Manohar, "Yasoverman of Kanau ", pp56

- Atherton, Cynthia P., "The Sculpture of Early Medieval Rajastann", pp14

- Bhandarkar 1929, pp. 29–30; Wink 2002, p. 208

- Blankinship, Khalid Y, "The End of Jihad State ", pp133

- Misra, Shyam, Manohar, "Yasoverman of Kanau ", pp45

- Bhandarkar 1929, pp. 30–31; Rāya 1939, p. 125; Majumdar 1977, p. 267; Puri 1986, p. 46; Wink 2002, p. 208

- Puri 1986, p. 46; Wink 2002, p. 209

- Bhandarkar 1929, pp. 29–30; Majumdar 1977, pp. 266–267; Puri 1986, p. 45; Wink 2002, p. 208; Sen 1999, p. 348

- Elliot, Henry, "Historians of India: Appendix The Arabs in Sind, Vol III, Part 1", pp51

- Editors = Idris El Harer, El Hadje Ravane M'Baye, "The Spread of Islam Throughout The World", pp613

- Wink (2002), pg.210

- Editors = Idris El Harer, El Hadje Ravane M'Baye, "The Spread of Islam Throughout The World", pp614

- Editors: Bosworth, C.E. &Asimov, M.S, "History of Civilizations of Central Asia " Vol IV, pp298 – pp301

- Alberuni's India. (c. 1030 AD). Translated and annotated by Edward C. Sachau in two volumes. Kegana Paul, Trench, Trübner, London. (1910). Vol. I, p. 22.

- Henry Walter Bellow. The races of Afghanistan: Being a brief account of the principal nations inhabiting that country (1880). Asian Educational services. p. 73.

- Satish Chandra, Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals (1206–1526), (Har-Anand Publications, 2006), 25.

- A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East, Vol. I, ed. Spencer C. Tucker, (ABC-CLIO, 2010), 263.

- International Encyclopaedia of Islamic Dynasties by Nagendra Kr Singh, Nagendra Kumar Singh. Published by Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. 2000 Page 28 ISBN 81-261-0403-1, ISBN 978-81-261-0403-1

- Ira M. Lapidus, A History of Islamic Societies 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press 2002

- "Mu'izz-al-Din Muhammad ibn Sam (Ghorid ruler of India)". Britannica Online Encyclopædia. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- Jamal Malik (2008). Islam in South Asia: A Short History. Brill Publishers. p. 104. ISBN 978-9004168596.

- Vijayanagar | historical city and empire, India | Britannica.com

- Sanyal, Sanjeev (15 November 2012). Land of seven rivers: History of India's Geography. Penguin Books Limited. pp. 130–1. ISBN 978-81-8475-671-5.

- B.F. Manz, "Tīmūr Lang", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Online Edition, 2006

- The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, "Timur", 6th ed., Columbia University Press: "... Timur (timoor') or Tamerlane (tăm'urlān), c.1336–1405, Mongol conqueror, b. Kesh, near Samarkand. ...", (LINK)

- "Timur", in Encyclopædia Britannica: "... [Timur] was a member of the Turkic Barlas clan of Mongols..."

- "Baber", in Encyclopædia Britannica: "... Baber first tried to recover Samarkand, the former capital of the empire founded by his Mongol ancestor Timur Lenk ..."

- Volume III: To the Year A.D. 1398, Chapter: XVIII. Malfúzát-i Tímúrí, or Túzak-i Tímúrí: The Autobiography or Memoirs of Emperor Tímúr (Taimur the lame). Page 389. 1. Online copy Archived 3 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- The Islamic World to 1600: The Mongol Invasions (The Timurid Empire) Archived 16 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Hari Ram Gupta (1994). History of the Sikhs: The Sikh Gurus. ISBN 8121502764. See page 13

- Volume III: To the Year A.D. 1398, Chapter: XVIII. Malfúzát-i Tímúrí, or Túzak-i Tímúrí: The Autobiography or Memoirs of Emperor Tímúr (Taimur the lame). Page: 389 Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine (1. Online copy Archived 3 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 2. Online copy) from: Elliot, Sir H. M., Edited by Dowson, John. The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. The Muhammadan Period; London Trubner Company 1867–1877.

- Lane-Poole, Stanley (1907). "Chapter IX: Tinur's Account of His Invasion". History of India. The Grolier Society. Full text at Google Books

- B.F. Manz, "Tīmūr Lang", in Encyclopaedia of Islam.

- Timur in the Political Tradition and Historiography of Mughal India

- Timur in the Political Tradition and Historiography of Mughal India, Irfan Habib, p. 295-312

- Dhillon, Dalbir Singh (1988). Sikhism Origin and Development.

- Lal, K S. "3: Proselytization in Provincial Muslim Kingdoms". Indian Muslims: Who are They?. New Delhi: Voice of India.

In conclusion it may be emphasised that even when historical forces had divided the country into a number of independent states consequent on the break-up of the Delhi Sultanate, the work of proselytization continued unabated. Indeed, it made the task of conversion easy. Small regions could be dealt with in detail and severe Muslim rulers, orthodox Ulema and zealous Sufis worked in them effectively. It was due to extraordinary situations that the Kashmir valley and Eastern Bengal became Muslim-majority regions as far back as the fifteenth century. In other parts of the country, where there was a Muslim ruler, Muslim population grew apace in the normal and usual way.

- Haidar, Navina Najat; Sardar, Marika (2015). Sultans of Deccan India, 1500–1700: Opulence and Fantasy. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780300211108.

Deccan sultanates.

- Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. p. 119. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- Annemarie Schimmel, Classical Urdu Literature from the Beginning to Iqbāl, (Otto Harrasowitz, 1975), 143.

- Brian Spooner and William L. Hanaway, Literacy in the Persianate World: Writing and the Social Order, (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012), 317.

- "Barīd Shāhī dynasty | Muslim dynasty". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- Robert Sewell. Lists of inscriptions, and sketch of the dynasties of southern India (The New Cambridge History of India Vol. I:7), Printed by E. Keys at the Government Press, 1884

- "The Five Kingdoms of the Bahmani Sultanate". orbat.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2007. Retrieved 5 January 2007.

- Census of India, 1991: Mahbubnagar. Government of Andhra Pradesh. 1994.

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2008). Historical Dictionary of Medieval India. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810855038.

- Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002). History of Medieval India: From 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. p. 101.

- Ferishta, Mahomed Kasim (1829). History of the Rise of the Mahometan Power in India, till the year A.D. 1612 Volume III. Translated by Briggs, John. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green.

- Young Hindu Girl Before the Mughal Emperor Akbar, in The Walters Art Museum.

- S. M. Ikram (1964). "XIX. A Century of Political Decline: 1707–1803". In Ainslie T. Embree. Muslim Civilization in India. New York: Columbia University Press. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- Asger Christensen. "Aiding Afghanistan: The Background and Prospects for Reconstruction in a Fragmented Society" pp 12. NIAS Press, 1995. ISBN 8787062445

- Hamid Wahed Alikuzai. "A Concise History of Afghanistan in 25 Volumes, volume 14." pp. 202. Trafford Publishing, 2013. ISBN 1490714413

- A Popular Dictionary of Sikhism: Sikh Religion and Philosophy, p.86, Routledge, W. Owen Cole, Piara Singh Sambhi, 2005

- Islamic Renaissance In South Asia (1707–1867) : The Role Of Shah Waliallah ... – M.A.Ghazi – Google Books

- "The Marathas", in Encyclopædia Britannica

- "Bal Gangadhar Tilak", in Encyclopædia Britannica

- Elphinstone, Mountstuart; Cowell, Edward Byles (1866). The History of India: The Hindú and Mahometan Periods.

- Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313335372.

- Sarkar, Jadunath (1988). Fall of the Mughal Empire: 1789-1803. Sangam. ISBN 9780861317493.

- Mehta, J. L. Advanced study in the history of modern India 1707–1813

- Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 ... 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- War, Culture and Society in Early Modern South Asia, 1740–1849 – Kaushik Roy, Lecturer Department of History Kaushik Roy. 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- The Great Maratha Mahadaji Scindia – N. G. Rathod – Google Books. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- Singh, Ganda (1959). Ahmad Shah Durrani: Father of Modern Afghanistan (PDF). Asia Publishing House. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- History of the Marathas – R.S. Chaurasia. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- Glover, William J (2008). Making Lahore Modern: Constructing and Imagining a Colonial City. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816650217.

- Adamec, Ludwig W (2011). Historical Dictionary of Afghanistan. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810879577.

- Griffin, Lepel H; Griffin, Sir Lepel Henry (1905). Ranjit Singh and the Sikh Barrier Between Our Growing Empire and Central Asia. Clarendon Press. ISBN 9788120619180.

- Hunter, William Wilson (2004). Ranjit Singh: And the Sikh Barrier Between British Empire and Central Asia. ISBN 9788130700304.

- Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges. Lancer Publishers & Distributors. ISBN 9780313335396.

- Singh, Harbakhsh (July 2010). War Despatches: Indo-Pak Conflict 1965. APH Publishing. ISBN 9781935501299.

- Will Durant. The Story of Civilization: Our Oriental Heritage. p. 459.

- der Veer, pg 27–29

- Eaton, Richard M. The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1993 1993. Retrieved 1 May 2007

- Caste in Indian Muslim Society

- Aggarwal, Patrap (1978). Caste and Social Stratification Among Muslims in India. Manohar.

- S.A.A. Rizvi The Wonder That Was India – II

- Islam and the sub-continent – appraising its impact Archived 25 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Matthew White (2011). Atrocitology: Humanity's 100 Deadliest Achievements. Canongate Books. p. 113. ISBN 9780857861252.

- Malešević, Siniša (13 April 2017). The Rise of Organised Brutality. Cambridge University Press. p. 119. ISBN 9781107095625.

- McLeod (2002), pg. 33

- Pradhan 2012, p. 3.

- Hamilton 1819, pp. 129-132.

- Regmi 1961, p. 14.

- Wright 1877, pp. 167-168.

- Hamilton 1819, pp. 240-244.

- Hamilton 1819, pp. 12-13,15-16.

- Ram 1996, p. 77.

- Todd 1950, p. 209.

- Hitchcock 1978, pp. 112-113.

- Whelpton 2005, p. 10.

- Pandey 1997, p. 507.

- Eaton, Richard (September 2000). "Temple Desecration and Indo-Muslim States". Journal of Islamic Studies. 11 (3): 283–319. doi:10.1093/jis/11.3.283.

- Robert Bradnock; Roma Bradnock (2000). India Handbook. McGraw-Hill. p. 959. ISBN 978-0-658-01151-1.

- Richard M. Eaton, Temple Desecration and Indo-Muslim States, Part II, Frontline, 5 January 2001, 70-77.

- Richard M. Eaton, Temple Desecration and Indo-Muslim States, Part I, Frontline, 22 December 2000, 62-70.

- Eaton, Richard M. (5 January 2001). "Temple Desecration and Indo-Muslim States" (PDF). Frontline. Chennai, India. p. 297. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2014.

- Annemarie Schimmel, Islam in the Indian Subcontinent, ISBN 978-9004061170, Brill Academic, pp 7-10

- James Brown (1949), The History of Islam in India, The Muslim World, 39(1), 11-25

- Eaton, Richard M. (December 2000). "Temple desecration in pre-modern India". Frontline. 17 (25).

- Eaton, Richard M. (2004). Temple desecration and Muslim states in medieval India. Gurgaon: Hope India Publications. ISBN 978-8178710273.

- Welch, Anthony (1993), Architectural patronage and the past: The Tughluq sultans of India, Muqarnas, Vol. 10, 311-322

- Welch, Anthony; Crane, Howard (1983). "The Tughluqs: Master Builders of the Delhi Sultanate" (PDF). Muqarnas. 1: 123–166. doi:10.2307/1523075. JSTOR 1523075. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2016.

- Richard Eaton, Temple Desecration and Muslim States in Medieval India at Google Books, (2004)

- Gul and Khan (2008), Growth and Development of Oriental Libraries in India, Library Philosophy and Practice, University of Nebrasaka-Lincoln

- Eva De Clercq (2010), ON JAINA APABHRAṂŚA PRAŚASTIS, Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hung. Volume 63 (3), pp 275–287