Reformation in the Kingdom of Hungary

The Reformation in the Kingdom of Hungary started around 1520 and resulted in the conversion of most Hungarians from Roman Catholicism to a Protestant denomination by the end of the 16th century. Hungary was a Central European regional power in the late 15th century. It was a multhiethnic composite monarchy with a significant non-Catholic, predominantly Greek Orthodox, population.

Background

Reformation in Europe

Mass was the central element of devotional life in Western Christianity in the Late Middle Ages. During the ceremony, bread and wine were served to commemorate Jesus's Last Supper before his crucifixion. The 13th-century scholastic theologian, Thomas Aquinas, developed the idea of transubstantiation, stating that the substance of the bread and wine turned into the substance of the Body and Blood of Christ during the liturgy of Eucharist. Most faithful believed that payers for the dead, indulgence grants from church authorities and works of mercy could shorten the afterlife sufferings of sinful people's souls.[1] Those who challenged traditional doctrines had to face persecution by church authorities.[2] Laymen's desire to a godly way of life developed a contemplative method of piety around 1400. This Devotio Moderna enabled ordinary people to embrace the clerics' high standards without taking the holy orders.[3]

An elaborate church organization secured the unity of Western Christianity. Clergymen—secular clerics and monks—were expected to remain celibate (unmarried and chaste). Secular clerics were organized into dioceses, each under a bishop's authority. A diocese included smaller territorial units, known as parishes. The monks lived a regulated life within religious communities, many of which formed international organizations. The pope stood at the head of the church organization, but the co-existence of two, later three, rival lines of popes subverted the traditional order during the Western Schism (from 1378 to 1417).[4] An Oxford theologian, John Wyclif, challenged the traditional ecclesiastic system in the 1370s. He rejected the clergymen's privileges, teaching that all faithful chosen by God had a direct access to an eternal invisible Church. His followers, the Lollards, were outlawed, but a royal marriage between England and Bohemia facilitated the spread of his teachings in Central Europe. A professor at the Prague University, Jan Hus, accepted some of Wyclif's views and his sermons demanding a Church reform won popularity among the Czechs. Hus was burned at the stake for heresy in 1415. Soon a civil war, colored with ethnic tensions between Czechs and Germans, broke out in Bohemia. It was closed by the Peace of Kutná Hora that legalized moderate Hussitism, or Utraquism, in Bohemia in 1485.[5][6]

From the early 15th century, manuscripts containing Classical Greek philosophers' works were streaming to Catholic Europe from the Byzantine Empire. Humanist men of letters rediscovered Plato and Plato's believe in a reality beyond visible reality diverted them from the clear categories of scholastic theology. The study of Classical texts convinced them that some of the key documents of church history were forgeries or unworthy collections of poor texts.[note 1][8] The spread of paper manufacturing and the introduction of printing machines with movable type had a lasting impact on religious life. Bibles translated from Latin to vernaculars were among the first books printed in Germany, Italy, Spain and Bohemia in the 1460s and 1470s.[9] The Dutch humanist Erasmus completed a critical edition of the Latin translation of the New Testament between 1516 and 1519. His translation challenged the textual basis of some Catholic doctrines, including the sacrament of penance and the intercession of saints.[10]

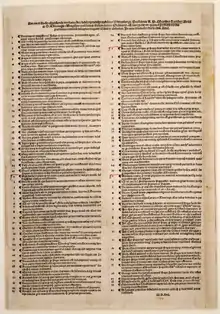

Pope Leo X decided to complete the building of the St. Peter's Basilica and issued indulgence grants to finance the project in 1515. Around the same time, the German theologian Martin Luther was delivering lectures on salvation at the Wittenberg University. His studies convinced him that indulgence grants were useless and summarized his views in his Ninety-five Theses on 31 October 1517.[11] The Pope excommunicated him for heresy,[12] but Luther publicly burned the papal bull in December 1520. Luther rejected the clerics' privileged status and denied that works of merit could influence salvation. Instead, he embraced the idea of sola fide, or justification by faith alone.[13][14] Luther's co-worker, Philip Melanchthon, summarized the principal theses of Evangelical theology in the Augsburg Confession in 1530. As the new theology gain popularity among the German princes, the principle cuius regio, eius religio ("whose realm, his religion") emerged, emphasizing the princes' right to regulate their subjects' spiritual life. Its application transformed Germany into a mozaic of predominantly Evangelical or Catholic principalities. The principle also established the secular rulers' claim to take responsibility for church administration and to seize church property.[15][16] In 1529, the princes and free cities sympathizing with Luther's theology staged a protest against the anti-Lutheran decisions adopted at Imperial Diet of Speyer, hence the name "Protestant" for 16th-century religious reformers and their followers.[17]

Luther's theology did not satisfy all reformers' expectations. He never abandoned his devotion to the Eucharist and insisted on the baptism of children. Under the influence of the parish priest, Huldrych Zwingli, who did not regard the Eucharist more than a symbolic act, the city council of Zürich outlawed the Mass in 1525. [18] A Catholic priest's illegitimate son, Heinrich Bullinger, developed an interim formula to conciliate Luther's and Zwingli's views on Eucharist, describing it as a mark of the covenant between God and humankind. The most radical reformers rejected the doctrine of Trinity (the believe in one God consisting of three persons, Father, Son and Holy Spirit). A Navarrese scholar, Michael Servetus, adopted this antitrinitarian theology in the hope of facilitating the union of Christianity, Islam and Judaism.[19] In 1534 Anabaptist radicals seized Münster, legalized polygyny and ordered the redistribution of property, but the local bishop crushed the revolt in a year.[20]

A French Protestant refugee who settled in Geneva John Calvin regarded the Anabaptists as fanatics.[21] To explain theological diversity, Calvin developed the idea of double predestination, stating that God had chosen some people for salvation, others for damnation.[22] He rejected the doctrine of transubstantiation and regarded the sacramental bread as a symbol of Christ's heavenly body.[23] Calvin's theology gave rise to the development of a new Protestant denomination, known as Reformed Christianity or Calvinism. Most German states and Scandinavia remained loyal to Luther's teachings, but English, French and Dutch translations of Calvin's works spread his ideas in Scotland, France and the Netherlands.[24] Theological debates brought about the "Era of Confessionalization": the Calvinists summarized their theologies in confessional documents, including the 1563 Heidelberg Catechism.[25]

The Reformation movement exerted influence on religious life and theology throughout Europe, but it thrived particularly in regions under a weak central authority.[26] Radical reformers' acts alarmed many people and the newly raised nostalgia for traditional church values gave an impetus to Catholic renewal, culminating in the Counter-Reformation. A courtier turned friar, Ignatius of Loyola, established a highly centralized religious order, the Society of Jesus. Popularly known as Jesuits, the Society's members were rather missionaries or teachers than ordinary priests from the 1550s.[27] The Council of Trent (1545–1563) passed decrees to renew and reinforce Catholic theology and church life. In response to Luther's concept about a sinful humanity unable to fulfil divine law, the Council emphasized that humankind retained free will after the Fall. The council's last session ordered the foundation of seminaries to secure the training of parish priests.[28]

Early Modern Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a Central European regional power, encompassing about 320,000 km2 (120,000 sq mi) of land in the 15th century. It was a composite monarchy: the Hungarian kings also ruled Croatia, and two provinces, Transylvania (in the east) and Slavonia (in the southwest), had their own peculiar administrative systems.[29] Hungary was a multi-ethnic realm, with most Hungarian-speakers living in the central regions and ethnic minorities—among them Slovaks, Romanians and Serbs—inhabiting the periphery.[30] Germans made up the majority of the townspeople. They had regular commercial contacts with the merchants of the Holy Roman Empire and many of them had family links with southern German and Silesian burghers.[31][32] Although predominantly Catholic, Hungary was a multi-confessional country, with a significant Orthodox population. The Orthodox had their own churches and practiced their religion without major restrictions.[33]

According to modern historians' estimations, the kingdom was home to 3–4 million people in the late 1490s. About 3,2–4,2% of the population were nobles.[34] About 90,000 burghers lived in the royal free boroughs; these were fortified towns and cities with extensive autonomy.[35] Conservative jurists argued that everybody else (those who were neither nobles nor burghers) were to be regarded serfs, but their approach ignored reality.[36] Townspeople in the market towns—unfortified settlements with the right to hold weekly markets—had a higher level of personal freedom than villagers.[37] Rural communities were also divided. Artisans were rewarded with tax-exemption, but most peasants paid seignorial taxes to their lords.[38]

The Royal Council was the composite kingdom's most important decision-making body. It was dominated by the realm's high officers and the Roman Catholic bishops. They also controlled the Diets, or legislative assemblies.[39] The peculiar administrative system of Transylvania had its origin in the co-existence of three privileged groups, known as "nations". The noblemen, known as the Hungarian nation, dominated the counties in central and western Transylvania. The Hungarian-speaking Székelys, who were responsible for the defence of eastern Transylvania, were organized into autonomous districts, or seats. The third nation, the German-speaking Transylvanian Saxons, inhabited parts of southern and northern Transylvania. They were also organized into seats and they elected their supreme leader, the Königsrichter, or royal judge. Some Saxon parishes were affiliated to the Bishopric of Transylvania, but the parishes in the church districts, or deaneries, of Hermannstadt and Kronstadt (now Sibiu and Brașov in Romania) were subject to the Archbishops of Esztergom. Bearing the title of primate, the archbishops were the heads of the Hungarian Catholic Church.[40]

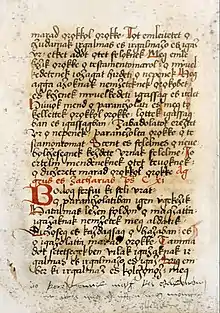

The Hungarian kings had extensive authority over church affairs. Papal decrees did not come into force without their assent and they controlled appointments to episcopal sees.[41][42] The Hungarian bishops' wealth was legendary, but they employed underpaid vicars to perform their spiritual duties.[43] The landowners held ius patronatus, or right of patronage, over the churches in their domains. The Diet also established their right to instal parish priests before their candidate was sanctioned by the bishop. On occasions, aristocrats consulted with the local communities before practicing their patronage right.[note 2] The royal free boroughs and the wealthy Upper Hungarian mining towns could freely elect and dismiss their parish priests. They preferred ethnic German clergy, but the town councils often appointed a junior cleric to take care of the spiritual needs of the local Hungarian- or Slovakian-speaking community.[45] Jan Hus's theology spread in the villages and market towns of Szerém County (now in Serbia) and Hussite preachers completed the Bible's first Hungarian translation. A papal inquisitor James of the Marches was appointed to purge the Hungarian Hussites in 1436.[46]

King Matthias Corvinus (r. 1458–1490) made his court a center of Humanism.[42] A member of the Florentine Platonic Academy, Francesco Bandini, was the King's close advisor and Bandini's friend, Marsilio Ficino, dedicated his treatise on salvation to Corvinus.[47] Humanistic ideas influenced a narrow circle of intellectuals.[48] Most Hungarians preferred the traditional forms of spirituality and the personal piety of the Devotio Moderna was alien to them.[38] Historian László Kontler describes the 16th century as "a particularly exciting period in the history of the Hungarian culture".[49] An educated nun, Lea Ráskay, wrote a collection of the lives of saints for nunneries in the 1510s and 1520s. Wealthy individuals and guilds granted large sums to finance the erection of splendid triptych altarpieces in several churches.[note 3][50]

After the expansion of the Ottoman Empire reached Hungary's southern frontier in the late 1380s, Hungary resisted Ottoman attacks for more than a century. In 1513, Pope Leo X declared a crusade against the Ottomans. About 40,000 Hungarian peasants took the cross, although the landowners tried to prevent their serfs from joining the campaign. Inflamed by radical Franciscan friars, the crusaders accused their lords of obstructing the holy war and rose up in an open rebellion under the command of György Dózsa. Their demands included the unification of the Hungarian bishoprics into one diocese and the redistribution of church property. After the Transylvanian voivode, or royal governor, John Zápolya, inflicted a crushing defeat on Dózsa's army on 15 July 1514, the peasant revolt was crushed and the Diet limited the peasants' right to free movement.[51][52] As the Hungarian kings could no more defend Croatia against Ottoman raids effectively, the Croatian aristocrats approached the neighboring Habsburg rulers for support.[53]

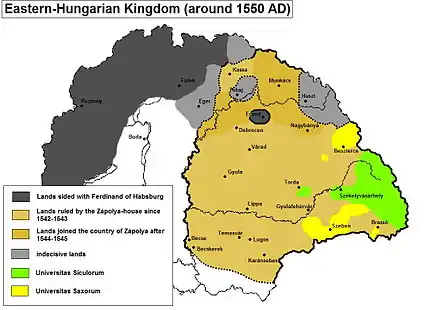

The Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent (r. 1520–1566) nearly annihilated the Hungarian army in the Battle of Mohács on 29 August 1526. The twenty-year-old King Louis II (r. 1516–1526) drowned in a stream fleeing from the battlefield. John Zápolya and Louis's brother-in-law, Ferdinand of Habsburg, laid claim to the throne. For both claimants were elected kings at two separate Diets, Hungary was plunged into civil war.[54][55] Regarding Hungary as a vassal state, Suleiman acknowledged John as the lawful king, but neither claimants could take control of the whole country. The two kings agreed to divide the country in the 1538 Treaty of Várad (Oradea, Romania), but the childless John acknowledged Ferdinand's right to reunite Hungary after his death. Days before John died in 1540, his wife, Isabella Jagiellon, gave birth to a son, John Sigismund. John's principal advisor, the Paulician monk, George Martinuzzi, persuaded John's partisans to elect the infant boy king. Ferdinand's troops stormed into John Sigismund's eastern Hungarian kingdom, providing Suleiman with a pretext to intervene. The Ottoman army invaded Hungary and seized the kingdom's capital, Buda, without resistance on 29 August 1541. Suleiman confirmed John Sigismund's right to rule the land to the east of the river Tisza and the Ottoman troops conquered the kingdom's central regions.[56][57]

As the Ottomans could never conquer the entire kingdom, its territory was divided into three parts.[58] The Habsburgs' realm, or Royal Hungary, included the western and northern regions; Martinuzzi assumed authority in the eastern Hungarian kingdom as regent for John Sigismund; and Ottoman Hungary became an integral part of the Ottoman Empire.[59] Two separate Diets, both regarded as the Hungarian Diets' legal successors, developed in Royal Hungary and in eastern Hungary. The latter Diet emerged from the joint assemblies of the representatives of the Three Nations of Transylvania and of the delegates of the nobility of the Partium (the eastern Hungarian counties along Transylvania's borders).[60] The eastern Hungarian Diet established each nation's right to regulate its own internal affairs.[61] Ottoman Hungary was divided into vilayets, or provinces, each under the rule of a beylerbey.[59] Most nobles fled from the territory and settled in the unoccupied territory.[62]

Martinuzzi enabled Ferdinand's mercenaries to take control of the eastern Hungarian kingdom in June 1551, forcing Queen Isabella and her son into exile. Martinuzzi was murdered by Ferdinand's henchmen, but the unpaid mercenaries could not prevent Ottoman attacks. In 1556, the Diet recalled John Sigismund and his mother from their exile. She ruled the country on her son's behalf until her death in 1559.[63][64] John Sigismund was the Sultan's loyal vassal and participated in several Ottoman military campaigns against Royal Hungary. During his reign, most Székelys were deprived of important elements of Székely liberties (such as tax exemption) which caused discontent in Székely Land.[65] Ferdinand's successor, Maximilian (r. 1564–1576), and Suleiman's son, Selim II (r. 1566–1574), restored peace in the Treaty of Adrianople in 1568. John Sigismund abandoned the title of king in his treaty with Maximilian in 1570, but continued to rule his realm using the title of Prince of Transylvania.[59] John Sigismund acknowledged the Habsburg kings' suzerainty[66] and their right to reunite Transylvania with Royal Hungary after his childless death.[67]

John Sigismund died in early 1571. The Three Nations' delegates ignored Maximilian's claim to Transylvania and elected a wealthy aristocrat Stephen Báthory (r. 1571–1586) ruler. Báthory was the Ottomans' candidate, but he swore fealty to Maximilian in secret.[68] Báthory was elected the ruler of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1575, but he maintained peace with the Ottomans and the Habsburgs. Maximilian was succeeded by his son, Rudolph (r. 1576–1608).[69] After Báthory was succeeded by his underage nephew, Sigismund Báthory (r. 1586–1599), factionalism developed and faction leaders conducted vendettas against their opponents in the Transylvanian principality.[70] Ottoman raids into Royal Hungary resumed and Sultan Murad III (r. 1574–1595) declared war against Rudolph in 1593. Unexpected Ottoman defeats during the first phase of the Long Turkish War strengthened anti-Ottoman sentiments and Sigismund Báthory concluded an alliance with Rudolph in 1595. The Ottomans quickly regained the initiative and Transylvania plunged into anarchy. In 1601, Rudolph's troops occupied the principality and his lieutenant, Giorgio Basta, introduced the rule of terror. The royal officials' arbitrary actions caused discontent in both Royal Hungary and Transylvania. Sigismund Báthory's maternal uncle, Stephen Bocskai, stirred up a revolt and occupied significant territory in Royal Hungary. The Treaty of Vienna restored peace and the Habsburgs acknowledged the re-establishment of the Transylvanian principality.[71]

Beginnings

News of Luther's activity reached Hungary shortly after he published his Ninety-five Theses.[72] Merchants from Hermannstadt likely learnt of Luther's ideas at the Leipzig Trade Fair in 1519.[73] One Thomas Preisner gave the first documented public reading of Luther's theses in Leibitz (Ľubica, Slovakia) in 1521. In a year, the German townspeople were enthusiastically discussing Luther's views in the Upper Hungarian mining towns. King Louis's guardian, George, Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach, entered into correspondence with Luther. Most German courtiers of Louis's wife, Mary of Habsburg, symphatized with the reformist ideas, but she did not abandon her Catholic faith. Her chaplain, Konrad Cordatus, made no secret of his adherence to Lutheran theology and she dismissed him after the Pope excommunicated Luther.[74] The Königsrichter, Markus Pemfflinger, supported the spread of Lutheran ideas in Hermannstadt where songs mocking the "Papists", or Catholics, gained popularity.[75]

Papist sect, you wretched people!

Look into yourselves and cast off your sins!

The fields are now green, the flowers are blooming,

And words full of meaning pour into the world.— Excerpt from a popular anti-Catholic Saxon song (c. 1524)[76]

The country's Hungarian- or Slavic-speaking population had no direct access to reformist literature for years.[58] Most nobles were hostile towards Protestant ideas, because they were convinced Hungary could resist Ottoman invasions only with the Pope's support. István Werbőczy who represented Hungary at the Imperial Diet of Worms in 1521 entered into a public argument with Luther. Luther stated that the Hungarians should fight against their own sins rather than against the Ottomans whom he regarded as "God's scourge". The Hungarian noblemen took his words as an insult, denying their self-declared mission of serving at the bulwark of Christianity.[77] The first anti-Lutheran edict was promulgated in Hungary on 24 April 1523; it ordered the persecution and execution of all Lutherans and the confiscation of their property. Ladislaus Szalkai, Archbishop of Esztergom, appointed commissioners to detect and destroy Evangelical literature, but the local magistrates obstructed them.[78][79] In Sopron, a royal commission experienced that townspeople regularly gathered in taverns to discuss Luther's views and to criticize the Pope.[80]

Anti-Lutheran legislation could not be enforced during the civil war that followed the Battle of Mohács.[79] Six of the twelve Hungarian bishops perished at the battlefield. King Ferdinand appointed bishops to the vacant sees, but the Pope did not confirm them. Church property was unprotected; church buildings and monasteries were regularly sacked or expropriated.[81] Neither king wanted to antagonize Protestant town leaders and aristocrats.[82] Protestant itinerant preachers freely crossed the frontiers between Hungary and King Ferdinand's other realms.[79] Some of them called themselves Neo-Utraquists to take advantage of the legal status of Utraquism in Bohemia.[6] King John's most prominent supporters, mainly nationalist aristocrats, looked on Luther as a German innovator and remained unsympathetic towards him. John was a devout Catholic, but he was unwilling to persecute "heretics" after the Pope excommunicated him for his alliance with the Ottomans in 1529.[83] Fear of social unrest hindered the spread of Protestant ideas, but no peasant movements followed the 1514 peasant war, because the serfs easily extracted exemptions from their lords in the wake of the Ottoman expansion.[84]

Laymen played a preeminent role in the dissemination and reception of reformist ideas.[84] Both Luther's denial of priestly privileges and Zwingli's picture of the reform movement as a force transforming church and society alike endorsed lay participation.[85] The first Protestant evangelists were "lay people of both sexes" who preached outside church buildings—in private homes or in public places.[84] Most leaders of the towns with significant German population were receptive to anti-Catholic preaching.[58] Pemfflinger expelled the Catholic parish priest and the Dominican friars from Hermannstadt around 1530. The wealthy mining town, Neusohl (Banská Bystrica, Slovakia), employed Evangelical town pastors from 1530. Some senior magistrates tried to impede the Reformation, but they could rarely find Catholic priests to fill the vacant parishes. Town councils granted scholarships to young people for studies at Wittenberg and other academic centers of the Reformation, but professional Evangelical preachers were still rare. In the 1540s, a Croatian graduate from Wittenberg, Michael Radašin, was a most popular pastor in the mining towns. Some town councils were reluctant to pay a regular renumeration to the local clergy. The Neusohl town pastor, Martin Hanko, had to dedicate much time to the management of his pastorate's properties to support himself before the town agreed to exchange them for a fix salary. Some preachers' radicalism outraged the moderate townspeople. Wolfgang Schustel, had to leave Bartfeld (Bardejov, Slovakia) for his strict views of public piety in 1531; his successor, Esaias Lang, was expelled for his Anabaptist sympathies.[86] A moderate magistrate, Johannes Honter, prevented the town pastor from abolishing the rules of fasting in Kronstadt in 1539.[87]

Individuals who did not speak German became receptive to Protestant ideas in the 1530s.[88] Protestant preachers compared the Hungarians, suffering from Ottoman invasions, with the Jews in the Egyptian and Babilonian captivities, describing the Hungarians as a new chosen people, able to regain God's favor through demonstrating their faith.[note 4] In contrast to this attractive explanation, Catholic clerics emphasized that the Ottoman plight had been brought to the Hungarian people as a punishment for their sins. Protestant men of letters actively participated in international scholarly networks. Many of them studied at German and Swiss universities or had direct contact to the most influential Protestant theologians.[90]

Reformist aristocrats gave shelter to Protestant preachers in both kings' realms.[91] Some of them entered into correspondence with Luther or Melanchthon on theological issues.[note 5][92] A wealthy noblewoman, Katalin Frangepán, commissioned the humanist Benedek Komjáti to publish his Hungarian translation of the Epistles of St Paul.[50] The aristocrats' right of patronage over village churches, was instrumental in the insemination of Protestant ideas among the peasantry.[93] Tamás Nádasdy, Péter Perényi and Gáspár Drágffy were among the first barons to employ Protestant pastors in their castles.[94][95] János Sylvester, a graduate from the Cracow and Wittenberg universities, completed and published his Hungarian translation of the New Testament at Sárvár—the center of the Nádasdy domains—in 1541.[93] Nádasdy was a representative figure of religious transition. He employed both an Evangelical chaplain and a Catholic court preacher; he offered asylum to Anabaptist refugees, but gave donations to the Paulician monks; he corresponded both with Melanchthon and the Pope; his wife,[96] Orsolya Kanizsai, regularly used Calvinist terminology in her correspondence with him.[62] Protestant aristocrats ceded the village churches to the local Protestant congregations, thus transformed the originally Catholic parishes to Evangelical pastorages. Available evidence suggests that women did not preach in churches, thus the development of Protestant church structure limited the role of women in evangelization.[62]

Most ethnic Hungarian pastors were born in market towns and this background facilitated them to address the villagers' everyday concerns.[90] Ethnic Hungarians were exposed to reformist ideas in a period of intensive debates among concurring Protestant ideologies.[58] Two former Franciscan friars, Mátyás Dévai Bíró and Mihály Sztárai, and Sztárai's younger co-worker, István Szegedi Kiss, represented the "theological eclecticism" of their age. Dévai Bíró came under the influence of Luther and Melanchthon around 1530, but his deep loathing of the Mass made him an ardent opponent of the doctrine of transubstantiation, for which conservative Protestants regarded him as a "Sacramentarian". He was a popular pastor, serving in aristocratic courts and market towns in both kings' realms. Sztárai moved to Ottoman Hungary and established Protestant congregations in more than 120 settlements. Radical reformers attacked him for his conservative views on liturgy, but his unclear teaching on the Eucharist astonished Evangelical theologians.[95][90] Szegedi Kiss was influenced by Bullinger's Eucharistic theology.[97] His theological treaties were taught in Western European Protestant universities.[98]

Legalization

Evangelical Church

The Catholic Bishop of Transylvania, János Statileo, died in 1542. The bishopric was left vacant, its revenues were confiscated and Queen Isabella established the new royal court at the bishops' castle in Gyulafehérvár (Alba Iulia, Romania).[99] The Queen appointed vicars to administer the bishopric, but the vacancy left the Transylvanian Catholics without a potent leadership.[100] After the Ottomans captured Esztergom in 1543,[101] the archbishopric's see was transferred to Nagyszombat (Trnava, Slovakia) in Royal Hungary.[102]

Evangelical divine service first replaced Catholic liturgy in eastern Hungary in Kronstadt in October 1542.[103] The Saxons of Bistritz (Bistrița, Romania) destroyed the "idols" in their churches in late 1542, because they interpreted a Moldavian attack against the town as the sign of the wrath of God for their idolatry. George Martinuzzi wanted to bring the Saxon priests before court on charges of heresy, but moderate politicians convinced him and the Queen to hold a religious debate at the Diet in Gyulafehérvár in June 1543. The debate was undecided and the Saxon preachers left Gyulafehérvár unharmed. Johannes Honter published a small book, the Reformation Pamphlet, about the transformation of church life in Kronstadt. Not unlike other reformators, Honter was convinced that the changes could not be regarded as innovations, but as steps towards the restoration of Western Christianity's ancient purity. He argued that many actually unimportant elements of Catholic church life were alien to Orthodox travellers visiting Kronstad, a flourishing commercial center on the Hungarian–Wallachian border, and their frequent demands for an explanation raised doubts about fundamental Christian doctrines in uneducated people. The most senior Saxon cleric, Matthias Ramser, sent a copy of Honter's booklet to Luther, Melanchthon and Johannes Bugenhagen for a review. The three reviewers unanimously praised it for its clarity.[104][105]

Experiencing the government's unwillingness to take anti-Protestant measures, the Saxon leaders concluded that religious issues could be treated as each nation's internal affairs. In April 1544, religious issues were re-considered at the Diet at Torda (Turda, Romania) and the co-existence of the Catholic and Evangelical denominations was tacitly recognised: a decree warned travellers to respect the devotional customs of the town or village where they were staying. The Three Nations' representatives wanted to consolidate religious status quo and the Diet prohibited further religious innovations.[106] In November, the Saxon nation's general assembly ordered that all Saxon towns introduce Evangelical liturgy; next year, the villages were to follow suit.[107][108] Evangelical Reformation spread from Kronstadt to the nearby Székely seats, primarily through the mediation of the town's Székely guards and two suburbs' Hungarian citizens. A Székely aristocrat, Pál Daczó, was the Evangelical pastors' most influential protector in Székely Land. Some Székely nobles remained devout Catholic, like the Apor family, securing the survival of Catholic enclaves.[108][109] The Saxon magistrates supported the publication of Evangelical catechisms in Romanian. They proposed liturgical changes, but most Romanian Orthodox priests rejected them.[110] Gáspár Drágffy's widow, Anna Báthory, convened northern Partium's Hungarian pastors to a synod in Erdőd (Ardud, Romania). They adopted twelve articles based on the Augsburg Confession in September 1545.[111][112]

The spread of Calvinist theology and radical ideas disturbed both the Catholic and Evangelical aristocrats and magistrates.[113] In 1548, the eastern Hungarian Diet repeated the ban on religious innovations,[114] while the Diet of Royal Hungary outlawed the "Sacramentarians" and Anabaptists.[113] At the latter Diet, the royal free boroughs were blamed for lenience with radical preachers.[115] The Catholic bishops set up commissions to expel all Protestants from Royal Hungary, but the royal free boroughs' immunities prevented the commissioners from launching investigations within their walls. Knowing that King Ferdinand had practically legalized the Augsburg Confession at the 1530 Imperial Diet, the Evangelical communities compiled confessions of faith to demonstrate their congregatios' full compliace with it.[113] A schoolmaster from Bartfeld, Leonard Stöckel, completed the first such document in September 1549. His Confessio Pentapolitana sharply criticized "sacramentarian" and radical theologies. It was adopted by five Upper Hungarian royal free boroughs.[115]

The Ottomans were indifferent to Christian theological debates[116] and reformist ideas spread undisturbed in Ottoman Hungary. As the Ottoman authorities wanted to pacify the conquered territory, they were keen to maintain religious peace.[117] They regulated the local Christian communities' religious issues in "letters of approval". They did not disturb the Christians' church life, but the construction and restoration of churches was strictly controlled and the priests could not assemble to a synod without a special permission. According to contemporaneous reports, Ottoman officials favored Protestant pastors to Catholic clergy, with some of them going as far as attending Protestant church services. In contrast, a Reformed pastor serving at Tolna, Pál Thúri Farkas, noted that Ottoman officials regularly investigated the local Christians' views about the Islamic prophet, Muhammad, and the Christians could avoid punishment only if they pretended ignorance.[118] The wealthy Fuggers' representative in Hungary, Hans Dernschwam, noted in 1554 that the poor Hungarians living in Buda "had no comfort other than the Word of God, which the Lutherans preach more openly than the Papists."[119]

The eastern Hungarian Diet enacted the Saxon interpretation and declared religious issues as part of each nation's internal affairs in 1550. The principle was not questioned after Queen Isabella and her son were exiled to Poland in 1551. The Diet regularly urged both Catholics and Evangelicals to receive each other "with deference and friendliness". In 1551, Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca, Romania), a free royal borough with a mixed Saxon and Hungarian population, met with no official opposition when the town council introduced the Evangelical version of Reformation.[120] The unification of Royal Hungary and eastern Hungary under the Habsburgs' rule provoked an Ottoman invasion in 1552.[121] The Ottomans annexed the Banat and refugees from the region increased the Hungarian-speaking citizenry in Kolozsvár. The town pastor, Gáspár Heltai, although himself a Saxon, published a series of religious books in Hungarian, including his own Dialogue—a collection of novels and parables, illustrating Luther's moral theology.[122]

Reformed Church

The aristocrats' willingness to expand their privileges and Ottoman expansion created favorable circumstances for the reception of Calvinist theology. Nobles started to regard the right to choose between concurring Christian denominations as an important element of their liberties.[123] Bullinger addressed his Brevis et pia institutio to the Hungarians, praising them for their struggle against the Ottomans. His work gained popularity, facilitating the spread of his theological views.[124] Tensions between concurring Protestant ideologies intensified and public theological debates were regularly held. That a congregation dismissed a pastor who had lost a debate was not uncommon, while a charismatic pastor could convince his flock to adhere to a new theology.[90]

An experienced debater, Márton Kálmáncsehi, was installed as the town pastor of Partium's wealthy market town, Debrecen, in 1551. He had already been famed for his passionate sermons that outraged moderate Protestants. Rumour had it that he had baptized children with water from a trough for swine to illustrate what Christian freedom meant. As town pastor, he replaced the altar with a simple wooden table in the church and wore everyday clothing during worship service. In line with Bullinger's views, he regarded the sacramental bread and wine as pure signs and symbols, for which the town council accused him of heresy and the Evangelical pastors' regional synod excommunicated him in Körösladány. A wealthy Protestant aristocrat, Péter Petrovics, stood by Kálmáncsehi and supported him to preach his views in his domains in the Partium. In 1552, Kálmáncsehi held two synods for the pastors of the region at Beregszász (Berehove, Ukraine) and they adopted decrees reflecting Calvinist influence. The spread of Calvinist ideology could cause heated debates: a Catholic citizen murdered a Reformed pastor in Várad in May 1553.[111][125] Petrovics's Italian physician Francesco Stancaro had been expelled from Prussia for his teaching on Christology.[126] According to mainstream theology, Christ united a divine and a human nature in his person. Stancaro did not reject this approach, but taught that Christ mediated between God and humankind only in his humanity.[127] His unorthodox interpretation brought him into frequent conflicts with the Evangelical clergy.[128]

For the Transylvanian Saxons were King Ferdinand's faithful supporters, his officials did not intervene when the Saxon pastors elected their first superintendent, or bishop, Paul Wiener, a refugee from Ferdinand's Duchy of Carniola, in February 1553. The Saxons did not sever all links to the Catholic Church. When Nicolaus Olahus was installed as Archbishop of Esztergom, the deans of Hermanstadt and Kronstadt offered him to pay the customary "cathedral interests". Olahus urged the deans to abandon their "heretic" views, but they ignored his demands. Pál Bornemissza, the newly appointed Catholic bishop of Transylvania, convoked a synod to make preparation for the re-Catholization of the deaneries under his jurisdiction. Although the Saxons of Bistritz were ready to remit the customary fees to him, they stated that the bishop should "remain quiet and peaceful" in matters of conscience, liturgy and theology. The presence of Ferdinand's mercenaries strengthened the Catholics' position in eastern Hungary. The new bishop of Várad, Mátyás Zabardi, banned the Reformed clergy from his diocese. Protestant pastors who chose to remain were to adjust some obviously Calvinist decrees adopted at their previous synods to demonstrate their adherence to Evangelical theology.[129]

Political scene was changing quickly. When Ferdinand withdrew his mercenaries from Transylvania, Bornemissza left his diocese and the Transylvanian bishopric was left vacant.[129] In 1556, the Diet elected Petrovics vice-regent to govern the country until the return of Queen Isabella and John Sigismund. During the interregnum, Petrovics initiated a religious debate between Evangelical and Reformed preachers in Kolozsvár.[130] The Three Nations' delegates celebrated the Queen's and her son's return with much pomp in October 1556.[131] The Diet secularized all properties of the bishoprics of Transylvania and Várad.[99] The Queen strove for religious peace and the Diet decreed that "everyone might hold the faith of his choice, together with the new rites or the older ones, without offence to any". The wording is misleading: the decree did not enact religious tolerance, but promoted the peaceful co-habitation of Catholics and Evangelicals.[126] In practice, the Catholic priests' free movement was limited to Catholic aristocrats' domains.[132] In 1557, the Evangelical pastors held a synod and divided the Transylvanian church district along ethnic lines. Ferenc Dávid, Kolozsvár's popular town pastor, was elected the Hungarian district's first superintendent.[133] Dávid, as historian Gábor Barta emphasizes, had a "sceptical mind" that "drove him from one crisis of faith to another".[134] Around 1557, his studies of Zwinglian theology weakened his Lutheran conviction,[135] but he eagerly defended traditional Christology against Stancaro.[128] Although Stancaro had to leave Hungary, his Christology deeply influenced his pupil, Tamás Arany.[136]

Religious discussions continued. In June 1557, the two Transylvanian church districts' joint synod completed a common confessional document, the Kolozsvár Consensus. It mirrored Luther's views on Eucharist, but in September the Protestant pastors of Partium adopted a Calvinist formula. The Saxon priests sent a copy of the Kolozsvár Consensus for a review to Melanchthon. The next Diet incorporated Melanchthon's assessment in a decree and outlawed Sacramentarians, but the ban could not stop the development of Reformed theology. Szegedi's student, Péter Melius Juhász completed the first Eucharistic creed in Hungarian.[137] He defined the Eucharist as a symbolic commemoration of Christ's death in line with Reformed theology.[138] He convinced Dávid to attend the synod of the Reformed clerics of Partium in Várad in August 1559. As the synod adopted the Reformed creed with Dávid's consent, Dávid's rupture with the Evangelical Church was inevitable and he abdicated the superintendency.[135] In November, Hungarian pastors from Upper Hungary, Partium and Transylvania assembled at a joint synod in Marosvásárhely (Târgu Mureș, Romania) and adopted Melius's creed.[138] The German townspeople remained hostile towards Calvinism and seven Upper Hungarian mining towns adopted a common Lutheran confession of faith, the Confessio Heptapolitana.[115] Sometimes the local lords' patronage right was inadequate to stop the spread of Reformed ideas. The local congregation convinced Sárospatak's Evangelical lord, Gábor Perényi, to acknowledge its right to freely choose between Evangelical and Reformed Eucharistic liturgy.[139]

Archbishop Nicolaus Olahus founded a seminary for the education of the Catholic clergy in Nagyszombat in 1560. Next year, he established a Jesuit convent which developed into the Counter-Reformation's principal center in Royal Hungary.[140] Olahus tried to implement a ban against priests who had not received the holy orders from a Catholic bishop, but they were numerous and their congregations was unwilling to dismiss them. His action raised the Protestants' animus towards Catholic church authorities.[116]

King Ferdinand supported Catholic renewal, but John Sigismund adopted an open-minded approach in religious issues.[49][141] Historian Mihály Balázs proposes that John Sigismund wanted to identify his realm as "a haven for reform in sharp distinction from his Catholic Habsburg rivals".[142] After a series of debates between the Saxon Evangelical and the predominantly Hungarian Reformed pastors, he persuaded both parties to summarize their views in two separate documents and sent both summaries to German Protestant theologians for a review in 1562. The same year, he converted from Catholicism to Evangelism, but did not forbade further religious debates. A decisive debate was held at Nagyenyed (Aiud, Romania) in April 1564. John Sigismund's antitrinitarian physician Giorgio Biandrata who represented him at the meeting advanced the election of two separate superintendents before the discussions started, making the separation of the Evangelical and Reformed churches practically inevitabe. The Reformed priests chose Dávid. On 4 June 1564, the Diet of Torda sanctioned the existence of the Reformed Church as the third religio recepta, or legally acknowledged denomination, in eastern Hungary. The same year, John Sigismund converted to Calvinism.[143]

Although two Calvinist leaders, Dávid and Heltai, were of Saxon origin, primarily ethnic Hungarians (including the majority of the Székelys)[144] chose to adhere to the Reformed Church.[145] The two Protestant denominations initially had no separate church organizations. The predominantly Reformed religio Colosvariensis ("Church of Kolozsvár") held jurisdiction over the counties, including the local Evangelical congregations, while the primarily Evangelical religio Cibiniensis ("Church of Hermannstadt") also included Reformed congregations in the Saxon seats.[146] To promote the Romanians' conversion to Calvinism, John Sigismund appointed a Protestant Romanian priest, Gheorghe of Sîngeorgiu, as their sole religious leader in 1566. The Diet ordered the expulsion of all Orthodox priests who refused to convert to Calvinism, but the decree was never implemented.[147]

Unitarian Church

Religious innovations continued in eastern Hungary and the most radical preachers started to openly reject the dogma of Trinity early in the 1560s.[148] One of them, Tamás Arany was banned from Debrecen by Péter Melius.[136] Giorgio Biandrata stated that all discussions about Christ's nature are unbiblical because God did not want to reveal all theological secrets to humankind.[149] He recognized that the Reformed congregations' autonomy facilitated the spread of radical views and convinced Ferenc Dávid to abandon trinitarian theology.[136][150] Dávid endorsed a radical theology, but he did not embrace most radical reformers' political activism.[151] In his publication of texts from Servetus's works, Dávid emphasized Christ's poverty, but also stated that Christ's example should be followed "to the extent that it was possible to do so".[152] The Kolozsvár magistrates appreciated Dávid's social conservativism and ordered the local pastors to comply with Dávid's teaching. Between 1566 and 1570, Kolozsvár became predominantly antitrinitarian, with repressed Reformed and Catholic minority communities.[134][148]

For Melius harshly criticized Dávid, King John Sigismund ordered them to discuss their views in public at Gyulafehérvár in April 1566. After the debate, John Sigismund praised Melius, and the Transylvanian clergy reassured their adherence to the dogma of Trinity. Dávid ignored their decision and refused to abandon antitrinitarianism. In February 1567, Melius held a synod in Debrecen, condemning Dávid and Dávid's followers for heresy.[153] The synod adopted a strictly Reformed confession of faith, known as Debrecen Confession, and ordered the removal of altars, organs and artefacts from the churches. The assembled pastors attacked the Papacy, associating it with the Antichrist, and blamed the "Papists" for replacing pure Christianity with their superstitions and doubtful traditions.[154] Biandrata as court physician, and Dávid as court preacher exercised significant influence on John Sigismund.[153] Antitrinitarianism well suited to his realm's international position: the adoption of an antitrinitarian theology expressed a distance from mainstream Christianity, without severing all links to it.[155] In February 1567, Dávid summoned the Transylvanian Reformed clerics to a synod at Torda. As the most devout Calvinist pastors absented themselves, the synod adopted a new creed, representing an interim position between trinitarian and antitrinitarian theologies. The creed acknowledged Christ as God's only son, described the Holy Spirit as a part of both God and Christ, but denied the Holy Spirit's independent personality. In the following months, Dávid summarized his theological views and critical comments on the Debrecen Confession in three Latin and two Hungarian treatises.[156]

John Sigismund convoked the Three Nations' delegates to a Diet in Torda in January 1568 to reconsider religious issues. The Diet passed an edict that expanded the limits of religious freedom in eastern Hungary.[157] The Edict of Torda authorized all pastors to freely preach their understanding of the Bible[158] and the local communities to freely determine their religious views.[151] In each parish, the majority confessional group could take possession of the local church building, but the displaced minority group was entitled to a compensation. Although landowners were forbidden to instal a priest in the churches under their patronage without the local community's consent, but the Hungarian, Saxon and Székely leaders strongly influenced the serfs' religious life in the lands under their rule.[159] In practice, the Edict of Torda granted the status of religio recepta to the antitrinitarian Transylvanian Unitarian Church.[49] The simple and attractive antitrinitarian slogan—"There is but one God"—facilitated mass conversions.[160] John Sigismund's Székely guards spread the new faith in Székely Land and prominent Székely aristocratic families converted to Unitarianism.[note 6][162] Some Székely communities' staunch Catholicism may have demonstrated their opposition to the King's attempts to limit their liberties. Hungarian noble families also chose Unitrianism, but most noblemen insisted on their Reformed, Evangelical or Catholic faith.[note 7][164] Unitarian church organization developed through the acquisition of Catholic church buildings together with the right to collect the tithes.[165]

A series of religious disputes between the three Protestant denominations' representatives followed the Diet. A Jesuit friar, János Leleszi, was allowed to attend the meetings as an observer. Secular leaders frequented the disputes and the theological arguments were presented in Hungarian for the first time in October 1569 in Várad. As John Sigismund did not hide his bias against trinitarian theology, his presence made the Reformed preachers uncomfortable. One of them, Péter Károlyi, made a complaint. In response, John Sigismund assured the Reformed pastors that he would never persecute them for their religious views, but he emphatically underlined that he would never allow Melius to expel antitrinitarian preachers from the Partium.[166]

Neither from us nor from our followers have you ever had to suffer injury. And that Péter Melius has been informed by our proclamation that he should not play the pope in our realm, persecuting clergy because of the true religion, nor burn books, nor force his belief on anyone, than it is for the following reason: We wish that in our country—and so it says in decree of the Diet—freedom shall reign. We know furthermore that faith is a gift from God and that conscience cannot be constrained. And if he does not abide by this, he may go to the other side of the Tisza.

— King John Sigismund's response to Péter Károlyi at the Várad debate (22 August 1568)[166]

John Sigismund's religious policy was unique in contemporaneous Europe. By the end of his reign, four legally acknowledged religions co-existed in his realm: Catholic communities survived primarily in Székely Land and Partium; the Saxons remained staunch supporters of their Evangelical Church; most Hungarians and Székelys adhered to Calvinism or Unitarianism.[167] The Edict of Torda, as historian Graeme Murdoch, concludes was "the product of the relative weakness of central political authority ... and intended to balance the interests the three nations represented in the diet."[158] Each acknowledged religion was supported by privileged groups—the leaders of the Hungarian, Saxon or Székely nations or the magistrates of the wealthy Kolozsvár.[167] Religious tolerance diminished the risk of confessional conflicts that could have been fatal to John Sigismund's nascent state.[158] Social radicalism was not tolerated. When a Polish pastor Elias Gczmidele proposed the establishment of a communitarian, egalitarian and pacifist congregation at Kolozsvár, Dávid achieved his dismissal.[152] The peasantry of the Partium was influenced by radical Anabaptist ideas. A charismatic Romanian serf, Gheorghe Crăciun, gathered a peasant army to establish the Kingdom of God in Earth in 1570. He led the armed peasantry against Debrecen, but Melius repelled the attack.[134][168]

The Habsburg kings of Royal Hungary did not tolerate Calvinist and antitrinitarian ideas. They regularly issued edicts against Sacramentarians in the 1560s and 1570s. The royal free boroughs and the nobility of the western counties remained staunch supporters of Lutheran theology. In contrast, aristocrats whose domains were located in the eastern counties employed Reformed priests and promoted the conversion of the local peasantry to Calvinism.[169] King Maximilian followed a more conciliatory religious policy than his father. Lazarus von Schwendi, who was one of his principal advistors, regarded religious tolerance as a precondition for the consolidation of the Habsburg Empire. Maximilian's tolerant policy was sharply criticized by his brother, Archduke Ferdinand.[170] The spread of Protestantism did not put an end to the Catholic Church's privileged position in Royal Hungary. The Catholic archbishops and bishops retained their seats in the Upper Chamber of the Diet and the Habsburg kings appointed their chancellors from among the Catholic prelates.[171]

Consolidation

John Sigismund's successor, Stephen Báthory, was a Catholic, but anti-Habsburg aristocrat. A Catholic aristocrat's election indicates that the predominantly Protestant Three Nations regareded their denominations' position secure.[172] He wanted to improve the Catholic Church's position. Although he could not regulate religious issues without the Diet's consent, he could take advantage of theological conflicts and exploit the instability of the Protestant denominations' church organization. He claimed the right to appoint the Evangelical superintendents from among three candidates proposed by the Saxon clergy and demanded the standardization of Evangelical liturgy along the lines of the most conservative ceremonies. He went so far that he tried to persuade the Evangelical pastors to condemnate their Reformed and Unitarian peers for heresy in clear contradiction to laws prohibiting attacks on priests on theological grounds. The Saxon priests resisted almost all his demands and they were willing only to declare their adherence to the Augsburg Confession (that was also Báthory's demand).[173] He was more successful in putting an end to the Romanians' enforced conversion to Calvinism. He restored the Orthodox church hierarchy and appointed a Moldavian monk, Eftimie, to head it. The Serbian patriarch, Makarije, ordained Eftimie bishop in April 1572.[174][175] Pockets of Reformed Romanian communities survived in the estates of Reformed aristocrats primarily in southwestern Transylvania.[176] Báthory could suppress antitrinitarian teaching in settlements with a religiously mixed population through exercising his patronage right.[177]

King Rudolph who succeeded his father in Royal Hungary abandoned Maximilian's tolerant policy and did not hide his favoritism towards Catholics.[170] Stephen Báthory persuaded the Diet to allow the Jesuits to settle in Transylvania in 1579. Two years later, he established a university for them in Kolozsvár. The first Jesuits came from Italy and Poland.[178] Although the Diet prohibited them to pursue missionary work,[179] they started recruiting among young Hungarian noblemen.[178]

The radicalism of some antitrinitarian intellectuals worried Stephen Báthory and he achieved a ban on further religious innovations at the Diet in May 1572.[170][180] The Diet authorized him to start investigations against suspected innovators together with a superintendent before the competent church authority. Without a superintendent's cooperation, state authorities were helpless against religious radicals. When three young antitrinitarian students challenged the doctrine of the immortality of the soul, Ferenc Dávid refused to initiate an invastigation against them. Dávid remained open towards radical ideologies and the Diet restricted the antitrinitarian preachers' right to hold synods to Kolozsvár and Torda.[178][181] In the 1570s, most leading figures of radical antitrinitarianism visited Transylvania. The former Dominican Jacob Palaeologus who rejected the doctrine of original sin and opposed the adoration of Christ stayed in Transylvania from 1573 to 1575. The German Matthias Vehe came in 1578. He emphasized that the faithful should live in accordance with the Law of Moses as set in the Old Testament. Dávid did not strove for the adoption of Jewish rituals, but he condemned the invocation of Christ, associating it with polytheism.[182] Discussions about religious issues were popular and a Reformed priest noted that the peasants often approached him with "questions about where the Trinity might be in the Bible".[183]

Dávid's rejection of the adoration of Christ outraged moderate antitrinitarians. Giorgio Biandrata invited the prominent antitrinitarian theologian Fausto Sozzini to Kolozsvár to dissuade Dávid from radicalism. After a synod approved Dávid's position about Jesus, Biandrata approached Stephen Báthory's brother and lieutenant, Christopher Báthory, persuading him to order Dávid's arrest for religious innovations in March 1579. Dávid was found guilty at the Diet and he died in the dungeon of Déva Castle.[184] Biandrata's candidate, Demeter Hunyadi, succeeded him as the new Unitarian superintendent. Hunyadi completed a confession of faith that reflected Sozzini's moderate theology. After an Unitarian synod accepted the document in early 1580, Hunyadi dismissed all pastors who rejected Christ's adoration, but radical noblemen continued to employ non-adorationist priests.[185] One of the radical aristocrats, János Gerendi, gave shelter to the poet Miklós Bogáthi Fazekas who proposed the restoration of the dietary laws of the Old Testament and regarded the Sabbath as the holy day of rest. Biandrata achieved an investigation at Gerendi's domain, forcing Bogáthi Fazekas to flee to Pécs in Ottoman Hungary.[186] Székely communities became open to radical antitrinitarianism during the Catholic Báthori's reign.[187] The Székely aristocrat, András Eőssi, who accepted Vehe's theology in the 1580s, was regarded as the founder of Székely Sabbatarianism.[188] The Sabbatarians who obeyed to all Mosaic laws distinguished themselves from Gerendi and his followers, who keep them selectively.[189]

In 1588, the Transylvanian Diet persuaded the young Sigismund Báthory to expulse the Jesuits from Transylvania in return for declaring him to be of age.[190] Báthory's favoritism towards Catholics was obvious and ambitious young Protestant aristocrats converted to Catholicism during his reign.[note 8] Pope Sixtus V appointed the Jesuit Alfonso Carillo to represent him in the Transylvanian court and Carillo became one of Báthory's most trusted advisors. Báthori purged the aristocrats who opposed his anti-Ottoman policy. Many of the executed noblemen were Unitarian and their relatives were often required to convert to Catholicism to receive a pardon.[note 9] The Jesuits could return to Transylvania and the Prince allowed the Catholic bishop of Transylvania, Demeter Naprágyi, to move to the old episcopal palace in Gyulafehérvár.[193]

In April 1595, the Diet did not only repeat the ban on religious innovations, but also ordered the heads of the counties and seats to persecute those who did not adhere to one of the four "received" denominations. The decree was directed against the Sabbatarians. The royal judge of Udvarhely Seat, Farkas Kornis, was known as radical Protestants' protector, but the seat's captain, Benedek Mindszenti, expelled many Sabbatarians from the seat. A Sabbatarian song would remember him as the "accursed captain". A Sabbatarian community wanted to approach the beylerbey of Buda offering to submit themselves to the Sultan in case of an Ottoman invasion, but their letter was intercepted. The Sabbatarians' persecution terminated when Mindszenti departed for a campaign against the Ottomans in September 1595.[194]

Uprising and peace

In 1603, King Rudolph announced that he was determined to exterminate the "godless heresy". Claiming the right of patronage over churches in royal free boroughs, he forced the predominantly Lutheran townspeople of Kassa (Košice, Slovakia) to cede their main church to the Catholics. The Protestant delegates protested against this action at the Diet, but the King arbitrarily supplemented the laws passed at the Diet with a clause ordering the persecution of heretics.[44] A decree prohibited the discussion of religious issues at the Diet in 1604.[195]

During the negotiations between Bocskai and the royal court, the Catholic clerics stroved for the enactment of the inviolability of the Catholic Church's privileges in return for acknowledging the legal status of the Evangelical and Reformed Churches. Instead, the Diet passed laws confirming the nobles' right to religious freedom and extending it to the free royal boroughs, to the market towns in the royal demesne and to soldiery of the border fortresses. The Diet established the jurisdiction of county courts to make judgement in disputes over tithes, authorized the Evangelical and Reformed senior clergy to pursue parish visitations and the titular bishops lost their seats in the Upper House.[196]

Impacts

Triumph of Protestantism

About 5,000 parishes existed in tripartite Hungary around 1600. Protestants dominated more than 3,700 parishes, implying that more than 75% of the population adhered to a Protestant denomination. The Reformed Church held about 1,150 churches in Transylvania proper and the Partium, 650 churches in Royal Hungary and 250 in Ottoman Hungary.[197] The Catholic Church had lost around 90% of its adherents.[198]

Vernacular culture

The Reformation laid the foundation of the use of native languages in scholarly debates[98] and brought about the first golden age of vernacular culture for the kingdom's most ethnic groups.[199] Dévai Bíró completed the first study of the Hungarian language in 1538.[98] Sylvester's translation of the New Testament was the first Hungarian book printed in Hungary.[200] An Evangelical catechism was published in Slovakian in Bartfeld in 1581.[201] Evangelical Slovakian pastors adopted a version of the Czech language for liturgical use, especially because many of them regarded the Czech Hussites as their forefathers.[202]

Protestants and Catholics alike attributed particular importance to education. The town council gained control of the parish schools in the Protestant towns. They established school authorities to oversee teaching programmes and relationship between teachers, schoolchildren and parents and appointed the town pastor to head it. Although individual teaching programmes and school regulations were compiled, they all followed patterns adopted from educational centers of Protestant Europe. The earliest school regulation was compiled by Stöckel at Bartfeld in 1540.[203] Basic education included the study of catechism. The town's school offered the opportunity to learn to read, write and count. Humanities were taught at high schools, or gymnasia and only those who wanted to study at universities were required to learn theology. Protestant aristocrats established schools on their domains. In response, a Catholic synod ordered the establishment of elementary schools in each rural parish in 1560.[201]

Interreligious relations

Honter' successor as town pastor in Kronstadt, Valentin Wagner, published a catechism in Greek, in preparation to an intensive dialogue with the Orthodox Church. He made references to Basil of Caesarea, Epiphanius of Salamis and other Church Fathers highly esteemed by the Orthodox community, but he proposed them not to hail Mary the Virgin as "God-bearer",[204] but call her "Son-bearer".[124]

Witch-hunting

Laws ordered the persecution of sorcery since the establishment of the Christian monarchy around 1000. Scattered documentary evidence shows that people were occasionally brought before courts for witchcraft, and some of them were burnt at the stake, but the regular persecution of witches started only in the 16th century.[205]

Notes

- In the early 1430s, Nicholas of Cusa demonstrated that the Donation of Constantine, a crucial document of papal authority, could not be written in the 4th century, as it had been claimed traditionally. Juan Luis Vives described the Golden Legend—a popular collection of saints' life—as a text "written by men with mouths of iron and hearts of lead".[7]

- For instance, the magistrates of the market town of Körmend persuaded their lord to replace the Augustinian friars with Franciscans in the local monastery.[44]

- Master Paul completed Europe's largest carved triptych in the main church in Leutschau (Levoča, Slovakia) between 1508 and 1518.[49]

- For instance, the Wittenberg graduate, András Farkas, comparised the Hungarians and the Jews in a song that gained popularity in the 1530s.[89]

- For instance, Ferenc Révay sought Luther's opinion on the Eucharist.[92]

- For instance, the Kornis, Petki, Dániel and Geréb families converted to Antitrinitarianism.[161]

- For instance, most Kendis adhered to antitrinitarian theology, but Sándor Kendi remained Lutheran.[163]

- Two young Unitarian nobles, Miklós Bogáthy and Ferenc Wass, who had studied at the Protestant Heidelberg University, continued their studies in Rome from 1592.[191]

- The executed Sándor Kendi's son, István, converted to Catholicism. Farkas Kovacsóczy's two sons studied at the Jesuits' school after their father was executed.[192]

References

- MacCulloch 2003, pp. 10–13, 17.

- Rees 1997, p. 24.

- MacCulloch 2003, pp. 22–24.

- MacCulloch 2003, pp. 26–27, 29–30, 34.

- MacCulloch 2003, pp. 34–37.

- Spiesz, Caplovic & Bolchazy 2006, p. 319 (note 4).

- MacCulloch 2003, pp. 78–79.

- MacCulloch 2003, pp. 74–79.

- MacCulloch 2003, pp. 68–71.

- MacCulloch 2003, pp. 94–97.

- MacCulloch 2003, pp. 116–119.

- Pettegree 1998, p. 4.

- MacCulloch 2003, pp. 124–127.

- Pettegree 1998, p. 17.

- Pettegree 1998, pp. 9, 20.

- MacCulloch 2003, p. 160.

- MacCulloch 2003, p. 166.

- MacCulloch 2003, pp. 132–142.

- MacCulloch 2003, pp. 172–174, 180–183.

- MacCulloch 2003, pp. 200–201.

- MacCulloch 2003, pp. 190, 230–233.

- MacCulloch 2003, pp. 236–237.

- MacCulloch 2003, pp. 242–243.

- MacCulloch 2003, pp. 307–310.

- MacCulloch 2003, p. 307.

- Pettegree 1998, pp. 3, 14.

- MacCulloch 2003, pp. 213–216, 218–219, 313.

- MacCulloch 2003, pp. 294–295.

- Pálffy 2009, pp. 18–19.

- Kontler 1999, p. 167.

- Daniel 1998, p. 52.

- Fata 2015, p. 104.

- Fata 2015, p. 94.

- Tringli 2003, pp. 127–129.

- Kontler 1999, p. 129.

- Tringli 2003, pp. 126, 130–131.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 106–107.

- Tringli 2003, pp. 131–132.

- Pálffy 2009, pp. 21–23.

- Keul 2009, pp. 29–36.

- Kontler 1999, p. 106.

- Rees 1997, p. 27.

- Daniel 1998, pp. 54–55.

- Fata 2015, p. 102.

- Fata 2015, pp. 94, 102, 105.

- Kontler 1999, p. 109.

- Rees 1997, pp. 29–30.

- Tringli 2003, p. 154.

- Kontler 1999, p. 152.

- Péter 1998, p. 155.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 103, 117–118, 134.

- Tringli 2003, pp. 41, 101–102.

- Fata 2015, p. 92.

- Murdoch 2000, p. 10.

- Tringli 2003, p. 107.

- Daniel 1998, pp. 49–51.

- Tringli 2003, pp. 117–121.

- Murdoch 2000, p. 11.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 144, 148–149.

- Barta 1994, p. 265.

- Keul 2009, p. 62.

- Péter 1998, p. 159.

- Keul 2009, pp. 40–41, 84–85, 86.

- Barta 1994, pp. 257–258.

- Barta 1994, pp. 283–284.

- Murdoch 2000, p. 13.

- Kontler 1999, p. 149.

- Barta 1994, p. 260.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 161–162.

- Barta 1994, pp. 293–294.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 162–163.

- Daniel 1998, p. 56.

- Keul 2009, p. 47.

- Daniel 1998, pp. 56–57.

- Keul 2009, pp. 48, 50.

- Keul 2009, p. 48 (note 4).

- Fata 2015, p. 95.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 150–151.

- Daniel 1998, p. 58.

- Fata 2015, pp. 106–107.

- Fata 2015, pp. 94–95.

- Péter 1998, p. 158.

- Keul 2009, p. 54.

- Péter 1998, p. 157.

- Szegedi 2009, p. 232.

- Daniel 1998, pp. 60–64.

- Keul 2009, p. 59.

- Daniel 1998, p. 59.

- Fata 2015, pp. 98–99.

- Kontler 1999, p. 151.

- Keul 2009, pp. 73–74.

- Péter 1998, pp. 158–159.

- Daniel 1998, p. 64.

- Keul 2009, p. 74.

- Daniel 1998, p. 65.

- Fata 2015, pp. 97–98.

- Daniel 1998, p. 66.

- Kontler 1999, p. 154.

- Szegedi 2009, p. 233.

- Keul 2009, p. 61.

- Kontler 1999, p. 146.

- Čičaj 2011, p. 74.

- Szegedi 2009, p. 230.

- Barta 1994, p. 287.

- Keul 2009, pp. 66–73, 75.

- Keul 2009, pp. 74–75.

- Keul 2009, p. 75.

- Szegedi 2009, p. 231.

- Balogh 2016, p. 181.

- Keul 2009, pp. 76–77.

- Barta 1994, p. 288.

- Péter 1998, p. 160.

- Daniel 1998, p. 67.

- Keul 2009, p. 84.

- Čičaj 2011, p. 73.

- Péter 1998, p. 162.

- Fata 2015, p. 93.

- Murdoch 2000, p. 24.

- Fata 2015, p. 98.

- Keul 2009, pp. 86, 89.

- Barta 1994, p. 258.

- Keul 2009, p. 89.

- Murdoch 2003, p. 12.

- MacCulloch 2003, p. 252.

- Keul 2009, pp. 94–95.

- Wilbur 1945, p. 22.

- Edmondson 2004, p. 14.

- Wilbur 1945, p. 23.

- Keul 2009, pp. 78, 86–88.

- Keul 2009, p. 95.

- Barta 1994, p. 259.

- Murdoch 2003, p. 21.

- Keul 2009, pp. 88–90.

- Barta 1994, p. 289.

- Keul 2009, p. 97.

- Keul 2009, pp. 106–107.

- Keul 2009, pp. 95–97.

- Murdoch 2000, p. 15.

- Fata 2015, pp. 101–102.

- Spiesz, Caplovic & Bolchazy 2006, p. 66.

- Keul 2009, p. 100.

- Balázs 2015, p. 182.

- Keul 2009, pp. 100, 103–104.

- Balogh 2016, p. 182.

- Murdoch 2000, p. 14.

- Fata 2015, p. 116.

- Keul 2009, pp. 104–105.

- Szegedi 2009, p. 235.

- Balázs 2015, pp. 175, 177.

- Balázs 2015, pp. 177–178.

- Szegedi 2009, p. 236.

- Balázs 2015, p. 179.

- Keul 2009, p. 108.

- Murdoch 2000, pp. 13, 17.

- Barta 1994, pp. 290–291.

- Keul 2009, pp. 108–111 (note 153).

- Keul 2009, p. 111.

- Murdoch 2000, p. 16.

- Murdoch 2000, p. 17.

- Keul 2009, p. 115.

- Balogh 2016, p. 183.

- Balogh 2016, pp. 182–183.

- Keul 2009, p. 125.

- Keul 2009, pp. 125, 130.

- Balázs 2015, p. 181.

- Keul 2009, pp. 114–115.

- Barta 1994, p. 290.

- Szegedi 2009, p. 238.

- Murdoch 2000, p. 22.

- MacCulloch 2003, p. 288.

- Murdoch 2000, pp. 21–22.

- Balázs 2015, p. 184.

- Keul 2009, pp. 117–118.

- Barta 1994, p. 292.

- Keul 2009, p. 134.

- Keul 2009, p. 135.

- Keul 2009, p. 120.

- Barta 1994, p. 291.

- Murdoch 2000, p. 21.

- Keul 2009, p. 119.

- Keul 2009, pp. 119–120.

- Balázs 2015, pp. 185–187.

- Keul 2009, p. 129.

- Keul 2009, pp. 120–122.

- Keul 2009, pp. 122–124.

- Szabó 1982, pp. 220–221.

- Keul 2009, p. 130.

- Szabó 1982, pp. 220–221, 224.

- Keul 2009, p. 133.

- Barta 1994, p. 293.

- Keul 2009, p. 128 (note 27).

- Keul 2009, pp. 139–140 (note 2).

- Keul 2009, pp. 127–129, 139–140.

- Keul 2009, pp. 140–141.

- Kontler 1999, p. 165.

- Fata 2015, p. 103.

- Murdoch 2000, p. 25.

- Péter 1998, p. 161.

- Péter 1998, p. 163.

- Fata 2015, p. 97.

- Čičaj 2011, p. 82.

- Spiesz, Caplovic & Bolchazy 2006, p. 68.

- Čičaj 2011, p. 81.

- Keul 2009, pp. 61, 81–82.

- Klaniczay 2001, pp. 219–220.

Sources

- Balázs, Mihály (2015). "Antitrinitarianism". In Louthan, Howard; Murdock, Graeme (eds.). A Companion to the Reformation in Central Europe. BRILL. pp. 171–194. ISBN 978-90-04-25527-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Balogh, Judit (2016). "Székelyek a fejedelemség politikai színterein: Vallásos sokszínűség". In Egyed, Ákos; Hermann, Gusztáv Mihály; Oborni, Teréz (eds.). Székelyföld története, II. kötet (1562–1867). MTA BTK, EME, HRM. pp. 181–189. ISBN 978-606-739-040-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barta, Gábor (1994). "The Emergence of the Principality and its First Crises (1526–1606)". In Köpeczi, Béla; Barta, Gábor; Bóna, István; Makkai, László; Szász, Zoltán; Borus, Judit (eds.). History of Transylvania. Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 247–300. ISBN 963-05-6703-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Čičaj, Viliam (2011). "The period of religious disturbances in Slovakia". In Teich, Mikuláš; Kováč, Dušan; Brown, Martin D. (eds.). Slovakia in History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 71–86. ISBN 978-0-521-80253-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daniel, David P. (1998) [1992]. "Hungary". In Pettegree, Andrew (ed.). The Early Reformation in Europe. Cambridge University Press. pp. 49–69. ISBN 978-0-521-39768-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Edmondson, Stephen (2004). Calvin's Christology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-54154-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fata, Márta (2015). "The Kingdom of Hungary and Principality of Transylvania". In Louthan, Howard; Murdock, Graeme (eds.). A Companion to the Reformation in Central Europe. BRILL. pp. 92–120. ISBN 978-90-04-25527-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Keul, István (2009). Early Modern Religious Communities in East-Central Europe: Ethnic Diversity, Denominational Plurality, and Corporative Politics in the Principality of Transylvania (1526–1691). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-17652-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Klaniczay, Gábor (2001) [1990]. "Hungary: The Accusations and the Universe of Popular Magic". In Ankarloo, Bengt; Henningsen, Gustav (eds.). Early Modern European Witchcraft: Centres and Peripheries. Oxford University Press. pp. 219–256. ISBN 0-19-820388-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kontler, László (1999). Millennium in Central Europe: A History of Hungary. Atlantisz Publishing House. ISBN 963-9165-37-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid (2003). The Reformation: A History. Viking. ISBN 0-670-03296-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Murdoch, Graeme (2000). Calvinism on the Frontier, 1600-1660: International Calvinism and the Reformed Church in Hungary and Transylvania. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820859-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pálffy, Géza (2009). The Kingdom of Hungary and the Habsburg Monarchy in the Sixteenth Century. Hungarian Studies Series. 18. Center for Hungarian Studies and Publications. ISBN 978-0-88033-633-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Péter, Katalin (1998) [1994]. "Hungary". In Scribner, Bob; Porter, Roy; Teich, Mikuláš (eds.). The Reformation in National Context. Cambridge University Press. pp. 155–167. ISBN 0-521-40960-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pettegree, Andrew (1998) [1992]. "The early Reformation in Europe: a German affair or an international movement". In Pettegree, Andrew (ed.). The Early Reformation in Europe. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-0-521-39768-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rees, Valery (1997). "Pre-Reformation changes in Hungary at the end of the fifteenth century". In Maag, Karin (ed.). The Reformation in Eastern and Central Europe. Ashgate. pp. 19–35. ISBN 1-85928-358-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spiesz, Anton; Caplovic, Dusan; Bolchazy, Ladislaus J. (2006) [2002]. Illustrated Slovak History: A Struggle for Sovereignty in Central Europe. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. ISBN 978-0-86516-426-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Szabó, Géza (1982). "A Hungarian antitrinitarian poet and theologian: Miklós Bogáti Fazakas". In Dán, Róbert; Pirnát, Antal (eds.). Antitrinitarianism in the Second Half of the 16th Century. Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 215–230. ISBN 963-05-2852-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Szegedi, Edit (2009). "The Reformation in Transylvania: New Denominational Identities; Confessionalization". In Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Nägler, Thomas; Magyari, András (eds.). The History of Transylvania, Vol. II (From 1541 to 1711). Romanian Academy, Center for Transylvanian Studies. pp. 229–254. ISBN 978-973-7784-04-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tringli, István (2003). Az újkor hajnala: Magyarország története, 1440–1541 [Dawn of the Modern Times: The History of Hungary, 1440–1541]. Magyar történelem. Vince Kiadó. ISBN 963-9323-92-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilbur, Earl Morse (1945). A History of Unitarianism: In Transylvania, England, and America. A History of Unitarianism. 2. Beacon Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Daniel, David P. (1998). "Calvinism in Hungary: the theological and ecclesiastical transition to the Reformed faith". In Pettegree, Andrew; Duke, Alastair; Lewis, Gillian (eds.). Calvinism in Europe, 1540-1620. Cambridge University Press. pp. 205–230. ISBN 0-521-57452-8.

- Evans, R. J. W. (1985). "Calvinism in East Central Europe: Hungary and Her Neighbours". In Prestwich, Menna (ed.). International Calvinism, 1541-1715. Clarendon Press. pp. 167–196. ISBN 9780198228745.