Polygyny

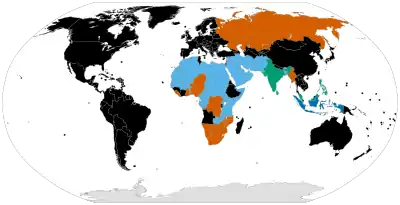

Polygyny (/pəˈlɪdʒɪniː/; from Neoclassical Greek πολυγυνία from πολύ- poly- "many", and γυνή gyne "woman" or "wife"[1]) is the most common and accepted form of polygamy, entailing the marriage of a man with several women. Most countries that permit polygyny are Muslim-majority countries.

- In Eritrea, India, the Philippines, Singapore, and Sri Lanka polygyny is only legal for Muslims.

- In Nigeria and South Africa, polygynous marriages based on customary law are legally recognized for Muslims.

- In Mauritius, polygynous unions have no legal recognition. However, Muslim men may "marry" up to four women, but they do not have the legal status of wives.

Relationships (Outline) |

|---|

| Part of a series on the |

| Anthropology of kinship |

|---|

|

|

Social anthropology Cultural anthropology |

Incidence

Polygyny is more widespread in Africa than in any other continent.[2] Some scholars see the slave trade's impact on the male-to-female sex ratio as a key factor in the emergence and fortification of polygynous practices in regions of Africa.[3] Generally in rural areas with growing populations, the higher the incidence of polygyny, the greater the delay of first marriage for young men. The higher the average polygyny rate, the greater the element of gerontocracy and social stratification.

Throughout the African polygyny belt stretching from Senegal in the west to Tanzania in the east, as many as a third to a half of married women are in polygynous unions, and polygyny is found especially in West Africa.[4] Historically, polygyny was partly accepted in ancient Hebrew society, in classical China, and in sporadic traditional Native American, African and Polynesian cultures. In the Indian subcontinent, it was known to have been practiced during ancient times. It was accepted in ancient Greece, until the Roman Empire and the Roman Catholic Church.

In North America, polygyny is practiced by some Mormon sects, such as the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS Church).[5][6]

Cause and explanation

Augmenting division of labor

Boserup (1970)[7] was the first to propose that the high incidence of polygyny in sub-Saharan Africa is rooted in the sexual division of labor in hoe-farming and the large economic contribution of women.

In some regions of shifting cultivation where polygyny is most frequently recorded, labor is often starkly divided between genders. In many of these cases, the task of felling trees in preparation of new plots, the fencing of fields against wild animals, and sometimes the planting of crops, is usually done by men and older boys (along with hunting, fishing and the raising of livestock).[8][9] Wives on the other hand, are responsible for other aspects of cultivating, processing and providing food for the family, and for performing domestic duties for the husband. Boserup notes that though the work completed by women calculates for a larger percentage of the tasks that form the basis of sub-Saharan life, women often do not receive the majority portion of the benefits that tag along with economic and agricultural success.

An elderly cultivator, with several wives and likely several young male children, benefits from having a much larger workforce within his household. By the combined efforts of his young sons and young wives, he may gradually expand his cultivation and become more prosperous. A man with a single wife has less help in cultivation and is likely to have little or no help for felling trees. According to Boserup's historical data, women living in such a structure also welcome one or more co-wives to share with them the burden of daily labor. However, the second wife will usually do the most tiresome work, almost as if she were a servant to the first wife, and will be inferior to the first wife in status.[10] A 1930s study of the Mende in the West African state of Sierra Leone concluded that a plurality of wives is an agricultural asset since a large number of women makes it unnecessary to employ wage laborers. Polygyny is considered an economic advantage in many rural areas. In some cases, the economic role of the additional wife enables the husband to enjoy more leisure.[11]

Anthropologist Jack Goody's comparative study of marriage around the world, using the Ethnographic Atlas, demonstrated a historical correlation between the practice of extensive shifting horticulture and polygyny in many Sub-Saharan African societies.[12] Drawing on the work of Ester Boserup, Goody notes that in some of the sparsely populated regions where shifting cultivation takes place in Africa, much of the work is done by women. This favored polygamous marriages in which men sought to monopolize the production of women "who are valued both as workers and as child bearers." Goody, however, observes that the correlation is imperfect, and also describes more traditionally male-dominated though relatively extensive farming systems such as those that exist in much of West Africa, particularly the savanna region, where more agricultural work is done by men, and polygamy is desired more for the production of male offspring whose labor in farming is valued.[13]

Goody's observation regarding African male farming systems is discussed and supported by anthropologists Douglas R. White and Michael L. Burton in "Causes of Polygyny: Ecology, Economy, Kinship, and Warfare",[14] where the authors note: "Goody (1973) argues against the female contributions hypothesis. He notes Dorjahn's (1959) comparison of East and West Africa, showing higher female agricultural contributions in East Africa and higher polygyny rates in West Africa, especially in the West African savanna, where one finds especially high male agricultural contributions. Goody says, "The reasons behind polygyny are sexual and reproductive rather than economic and productive" (1973:189), arguing that men marry polygynously to maximize their fertility and to obtain large households containing many young dependent males."[15][16]

An analysis by James Fenske (2012) found that child mortality and ecologically-related economic shocks had a stronger association with rates of polygamy in Subsaharan Africa rather than female agricultural contributions (which are typically relatively small in the West African savanna and sahel, where polygyny rates are higher), finding that polygyny rates decrease significantly with child mortality rates.[17]

Desire for progeny

Most research into the determinants of polygyny has focused on macro-level factors. Widespread polygyny is linked to the kinship groups that share descent from a common ancestor.[18] Polygyny also served as "a dynamic principle of family survival, growth, security, continuity, and prestige", especially as a socially approved mechanism that increases the number of adult workers immediately and the eventual workforce of resident children.[19]

According to scientific studies, the human mating system is considered to be moderately polygynous, based both on surveys of world populations,[20][21] and on characteristics of human reproductive physiology.[22][23][24]

Economic burden

Scholars have argued that in farming systems where men do most of the agriculture work, a second wife can be an economic burden rather than an asset. In order to feed an additional wife, the husband must either work harder himself or he must hire laborers to do part of the work. In such regions, polygyny is either non-existent or is a luxury which only a small minority of rich farmers can indulge.[10]

A report by the secretariat of the UN Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) quotes: "one of the strongest appeals of polygyny to men in Africa is precisely its economic aspect, for a man with several wives commands more land, can produce more food for his household and can achieve a high status due to the wealth which he can command".[10] According to Boserup, through the hard work, economic, and agricultural assistance of a man's many wives, a husband can afford to pay the bride price of a new wife and further his access to more land, meanwhile, expanding his progeny.[7] According to Esther Boserup, over much of the continent of Africa, tribal rules of land tenure are still in force. This implies that members of a tribe which commands a certain territory have a native right to take land under cultivation for food production and in many cases also for the cultivation of cash crops. Under this tenure system, an additional wife is an economic asset that helps the family to expand its production.

The economist Michèle Tertilt concludes that countries that practice polygyny are less economically stable than those that practice monogamy. Polygynous countries usually have a higher fertility rate, fewer savings reserves, and a lower GDP. Fertility would decrease by 40%, savings would increase by 70%, and GDP would increase by 170% if polygyny were banned.[3] Monogamous societies present a surge in economic productivity because monogamous men are able to save and invest their resources due to having fewer children. Polygynous societies have a higher concentration of men investing into methods of mating with women, whereas monogamous men invest more into their families and other related institutions.[25]

Despite the expenses of polygynous marriages, men benefit from marrying multiple wives through the economic and social insurance that kinship ties produce. With a large network of in-laws, these men have the ties they need to compensate for other economic shortages.[26]

Libido

Some analysts have posited that a high libido may be a factor in polygyny,[27] although others have downplayed its significance.[28] The sex drive as a factor in some Asian cultures was sometimes associated with wealthy men and those that were adjunct to an aristocracy,[29] although such libidinal perceptions were at times discarded in favor of seeing polygyny as a factor of traditional life.[30] For example, many Sub-Saharan African societies view polygyny as essential to expand their progeny and kinship, a practice of high cultural importance. In this case, it would be hard to determine whether the origins were that of high libido, as polygyny would be practiced regardless. Other explanations postulate that polygyny is a tool used to ward off inclinations towards infidelity.[31] In Edith Boserup's 1970 article on the study of Sub-Saharan African polygyny, higher incidences of adultery and prostitution were recorded in regions were polygyny was practiced, but delayed by males.[7]

Enslavement of women

Researchers have suggested that Vikings may have originally started sailing and raiding due to a need to seek out women from foreign lands.[32][33][34][35] The concept was expressed in the 11th century by historian Dudo of Saint-Quentin in his semi-imaginary History of The Normans.[36] Rich and powerful Viking men tended to have many wives and concubines, and these polygynous relationships may have led to a shortage of eligible women for the average Viking male. Due to this, the average Viking man could have been forced to perform riskier actions to gain wealth and power to be able to find suitable women.[37][38][39] Viking men would often buy or capture women and make them into their wives or concubines.[40][41] The Annals of Ulster states that in 821 the Vikings plundered an Irish village and "carried off a great number of women into captivity".[42]

Findings

Of the 1,231 societies listed in the 1980 Ethnographic Atlas, 186 were found to be monogamous; 453 had occasional polygyny; 588 had more frequent polygyny; and 4 had polyandry.[43] Some research that show that males living in polygynous marriages may live 12 percent longer.[44] Polygyny may be practiced where there is a lower male:female ratio; this may result from male infants having increased mortality from infectious diseases.[45]

Other research shows that polygyny is widely practiced where societies are destabilized, more violent, more likely to invade neighbors and more likely to fail.[46] This has been attributed to the inequality factor of polygyny, where if the richest and most powerful 10 percent of males have four wives each, the bottom 30 percent of males cannot marry. In the top 20 countries in the 2017 Fragile States Index, polygyny is widely practiced.[46] In West Africa, more than one-third of women are married to a man who has more than one wife, and a study of 240,000 children in 29 African countries has also shown that, after controlling for other factors, children in polygynous families were more likely to die young.[46] A 2019 study of 800 rural African ethnic groups published in the Journal of Conflict Resolution found that "young men who belong to polygynous groups feel that they are treated more unequally and are readier to use violence in comparison to those belonging to monogamous groups."[47]

In a 2011 doctoral thesis, anthropologist Kyle R. Gibson reviewed three studies documenting 1,208 suicide attacks from 1981 to 2007 and found that countries with higher polygyny rates correlated with greater production of suicide terrorists.[48][49] Political scientist Robert Pape has found that among Islamic suicide terrorists, 97 percent were unmarried and 84 percent were male (or if excluding the Kurdistan Workers' Party, 91 percent male),[50] while a study conducted by the U.S. military in Iraq in 2008 found that suicide bombers were almost always single men without children aged 18 to 30 (with a mean age of 22), and were typically students or employed in blue-collar occupations.[51] In addition to noting that countries where polygyny is widely practiced tend to have higher homicide rates and rates of rape, political scientists Valerie M. Hudson and Bradley Thayer have argued that because Islam is the only major religious tradition where polygyny is still largely condoned, the higher degrees of marital inequality in Islamic countries than most of the world causes them to have larger populations susceptible to suicide terrorism, and that promises of harems of virgins for martyrdom serves as a mechanism to mitigate in-group conflict within Islamic countries between alpha and non-alpha males by bringing esteem to the latter's families and redirecting their violence towards out-groups.[52]

Effects on women

Inequality between husbands and wives are common in countries where polygyny is more frequently practiced because of limited education. In Africa polygyny was believed to be part of the way to build an empire. It was not until the post colonialism era in Africa that polygyny began to be viewed as unjust or taboo. According to Natali Exposito, "in a study of the Ngwa Igbo Clan in Nigeria identified five principal reasons for men to maintain more than one wife: because having more than one wife allows the Ngwa husband to (1) have the many children that he desires; (2) heighten his prestige and boost his ego among his peers; (3) enhance his status within the community; (4) ensure a sufficient availability of labor to perform the necessary farm work and the processing of commercial oil-palm produce; and (5) satisfy his sexual urges."[53] Out of all of the reasons stated none are beneficial to the wives, but instead only beneficial to the husbands. In Egypt, feminists have fought for polygamy to be abolished, but it is viewed as a basic human right so the fight has been unsuccessful. In countries where polygyny is practiced less frequently, women have more equality in the marriage and are better able to communicate their opinions about family planning.[54]

Women participating in polygynous marriages share common marital problems with women in a monogamous marriage; however, there are issues uniquely related to polygyny which affects their overall life satisfaction and have severe implications for women's health.[55] Women practicing polygyny are susceptible to sexually transmitted diseases, infertility, and mental health complications.[54] Among the Logoli of Kenya, the fear of AIDS or becoming infected with the HIV virus has informed women's decisions about entering polygynous marriages. Some view polygyny as a means to prevent men from taking random sexual partners and potentially introducing STDs into relationships. Interviews conducted with some of the Logoli tribe in Kenya suggested they feared polygynous marriages because of what they have witnessed in the lives of other women who are currently in such relationships. The observed experiences of some of the women in polygynous unions tend to be characterized by frequent jealousy, conflicts, competition, tensions, and psychological stresses. Some of the husbands fail to share love and other resources equally; and envy and hatred, and sometimes violent physical confrontations become the order of the day among co-wives and their children. This discourages women from entering a polygynous marriage.[19] Research shows that competition and conflict can intensify to unbearable level for co-wives causing women to commit suicide due to psychological distress. Findings show that the wife order can affect life satisfaction. According to Bove and Valeggia, women who are senior wives often misuse their position to obtain healthcare benefits in countries where only one wife can become a recipient. The conflict between co-wives can attribute to the higher rates of mental health disorders and issues such as anxiety, depression, somatization, psychoticism, and paranoia. As well as this reduced marital/life satisfaction and low self-esteem has been shown to be more prevalent among women in polygynous relationships when compared to women in monogamous relationships.[55][56]

Various methods have been used to reduce the amount of jealousy and conflict among wives. These include sororal polygyny, in which the co-wives are sisters; and hut polygyny, in which each wife has her own residence and the husband visits them in rotation. A clear status hierarchy among wives is also sometimes used to avoid fighting by establishing unequivocally each wife's rights and obligations.[57] Although there are several harmful aspects of this practice related to women, there are some reported personal and economic advantages for women such as sharing household and child rearing responsibilities. Also, wives share companionship and support with co-wives.[54]

Studies of the Ngwa group in eastern Nigeria shows that on average, women in polygynous unions are 22-26% less fertile then women in monogamous unions. Data shows that the greater the intensity of polygyny, the lower the fertility of successive wives: 15 percent deficit for first wives; a 37% deficit for second wives; and a 46% deficit for third or more wives.[58] Studies show that seems to exist because of the widening age gap between the successive order of wives and because of the decreasing exposure to coitus, if all coitus occurs in marriage.[59]

Disease

Studies show there are two mechanisms that could lead to higher prevalence rates of HIV in men and women who are in polygynous unions: partners in polygynous unions have more extra-marital relationships and thus increase each other's exposure to HIV; women who are recruited into a polygynous union are more likely to be HIV positive than those who marry a monogamous husband.[60] In addition to these two mechanisms, variation in HIV prevalence rates by union type is possibly due to individuals in polygynous unions are typically part of a sexual network with concurrent partnerships.[60]

The ecological association between polygyny and HIV prevalence is shown to be negative at the sub-national level. HIV prevalence tends to be lower in countries where the practice of polygyny is common, and within countries it is lower in areas with higher levels of polygyny. Proposed explanations for the protective effect of polygyny include the distinctive structure of sexual networks produced by polygyny, the disproportionate recruitment of HIV positive women into marriages with a polygynous husband, and the lower coital frequency in conjugal dyads of polygynous marriages.[55]

For example, studies in Malawi have shown that for men and women in polygynous marriages, the rate of HIV is between 10-15%.[60] About 14% of Malawi's population is infected with HIV, which causes AIDS, according to official figures.[61] There are approximately 78,000 AIDS-related deaths and 100,000 new infections every year in the country.[61]

Criticism

The long-established criticism against polygyny stemmed from Thomas Aquinas nearly eight centuries ago. He contended that polygyny is unjust to wives and children.[62] He also argues that it creates rival stepchildren and forces them to compete for attention, food, and shelter. According to Aquinas, polygyny violates the “traditional” requirements of fidelity between husband and wife.[62]

Polygyny has been criticized by feminists such as Professor John O. Ifediora, who believes that women should be equal to men and not subject to them in marriage. Professor Ifediora also believes that polygyny is a "hindrance to social and economic development" in the continent of Africa due to women's lack of financial control.[63] Standard polygynist practices often leave women at a disadvantage if they make the decision to remove themselves from the polygynist lifestyle. To leave the marriage, women must repay their bride price. Though this is simple in thought, this is not simple in execution. To prevent their wives from leaving, husbands will often keep the bride price at high levels, which is often at an unpayable level for women.[64] In most cases, women do not have access to their children if they decide to leave polygyny, nor are they allowed to take them, due to cultural ideas of ownership in relation to progeny.

Premodern era

In Africa, the Americas, and Southeast Asia in the Premodern Era, circa 600 BCE – 1600 CE, both monogamy and polygyny occurred. Polygyny occurred even in areas of where monogamy was prevalent. Wealth played a key role in the development of family life during these times. Wealth meant the more powerful men had a principal wife and several secondary wives, known as resource polygyny. Local rulers of villages usually had the most wives as a sign of power and status. Conquerors of villages would often marry the daughters of the former leaders as a symbol of conquest. The practice of resource polygyny continued with the spread and expansion of Islam in Africa and Southeast Asia. Children born into these households were considered free. Children born to free or slave concubines were free, but had lesser status than those born to wives. Living arrangements varied between areas. In Africa, each wife usually had their own house, as well as property and animals. The idea that all property was owned by the husband originated in Europe and was not recognized in Africa. In many other parts of the world, wives lived together in seclusion, under one household. A harem (also known as a forbidden area) was a special part of the house for the wives.[65]

By country

Kenya

Polygynous marriage was preferred among the Logoli and other Abalulya sub ethnic groups. Taking additional wives was regarded as one of the fundamental indicators of a successfully established man. Large families enhanced the prestige of Logoli men. Logoli men with large families were also capable of obtaining justice, as they would be feared by people, who would not dare to use force to take their livestock or other goods from them. Interviews with some of the contemporary Logoli men and women who recently made polygynous marriages yielded data which suggest that marrying another wife is usually approached with considerable thought and deliberation by the man. It may or may not involve or require the consent of the other wives and prospective wife's parents. A type of "surrogate pregnancy" arrangement was reported to have been observed, in which some wives who are unable to bear children, find fulfillment in the children and family provided by a husband taking additional wives.[66] Some of the men indicated that they were pressured by their parents to marry another wife, who could contribute additional income to the family. Some of the young polygynous men indicated that they were trapped in polygyny because of the large number of single women who needed and were willing to take them as husbands although they were already married. Most of those second and third wives were older women who had not yet married.[19]

Nigeria

Customary law, one of the three legal systems in operation in Nigeria (the other two being Nigerian common law and Sharia law) allows for the legal marriage of more than one woman by a single man.

Unlike those marriages recognized by Sharia, there is no limit to the number of legal wives allowed under customary law. Currently polygyny is most common within royal and noble families within the country, and is largely practiced by the tribes native to its north and west. Although far less popular there, it is nonetheless also legal in Nigeria's east and south.

Polygyny varies according to a woman's age, religion and educational experience. Research conducted in the city of Ibadan, the second largest city in Nigeria, show that non-educated woman are significantly more likely (58%) to be in a polygynous union compared to college educated women (4%).[58] Followers of traditional African religions are expected to have as many wives as they can afford. Muslim men are allowed up to 4 women and only the basis he can care for and treat them equally. Christians are typically (and expected) to be monogamous.[58]

Among the Ngwa group in Eastern Nigeria, studies show that 70% of polygynous marriages consist of illiterate men and women, compared to 53% in monogamous marriages.[58]

Malawi

While polygynous marriages are not legally recognized under the civil marriage laws of Malawi, customary law affords a generous amount of benefits to polygynous unions, ranging from inheritance rights to child custody.[67] It has been estimated that nearly one in five women in Malawi live in polygynous relationships.[67]

Efforts to abolish the practice and de facto recognition of polygyny have been widely apparent throughout the recent years in Malawi; led mainly by anti-AIDS organizations and feminist groups. An effort led in 2008 to outlaw polygyny in the country was fiercely opposed by Islamic religious leaders, citing the practice as a cultural, religious and pragmatic reality of the nation.[68]

South Africa

Polygyny in South Africa is typically seen among the Muslim community, although polygynous unions overall are not widely practiced in South Africa among all religious and ethnic groups. Polygynous marriages of individuals over the age of 15 accounts for approximately 30,000 (0.1%) people in 2001. Both Islamic law and cultural family laws create a system in which Muslim men are encouraged to take up to four wives. Several factors for this include infertility or long-term illness of the first wife, excessive wealth on the part of the husband enabling him to support widowed or divorced mothers, and the economic benefits of large families.[69]

Despite the historical and cultural history of polygyny among Muslim South Africans, polygynous unions are officially illegal on the federal level in South Africa. After 1994, various laws such as the freedom of religion in the South African Constitution, the ratification of the UN's Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women and a proposed Draft Bill on Muslim Marriages have tackled the issue of Islamic polygynous unions in South Africa.[69]

Somalia

Polygyny is legal in Somalia and most commonly seen throughout Muslim communities. According to the Muslim tradition, men can have up to four wives. For a man to gain additional wives in Somalia, it must be granted by the court and it has to be proven that the first wife is either imprisoned or infertile.[70]

Mozambique

There are no legal restrictions against any polygynous marriages. As a result, polygyny is extensive throughout the country. There is an estimated report that over one-third of marriages in Mozambique.[71] However, under Mozambican law the first wife of the marriage is only legally recognized. The Mozambican government has also granted equal protection of inheritance rights for all wives within polygynous marriages as documented by an OECD finding.

Australia

Polygyny is not legal in Australia. The Marriage Act of 1961 under section 94 states that any person who knowingly marries another whose marriage is legally ongoing carries out the act of bigamy. The penalty of bigamy is up to five years of imprisonment. The Full Court of the Family Court of Australia ruled on March 6, 2016 that it is illegal to have polygamous marriages. However, foreign marriages that have potential to be polygamous when it was started will be legally recognized in Australia. The court defined a potentially polygamous marriage as if the marriage is not yet polygamous, but if the country where the marriage marginally taken place permits polygamous marriages of either partner to the original marriage at a later date. Indigenous populations of Australia have been noted to engage in polygamous relationships.

Asia

Many majority-Muslim countries retain the traditional sharia, which interprets teachings of the Quran to permit polygamy with up to four wives. Exceptions to this include Albania, Tunisia, Turkey, and former USSR republics. Though about 70% of the population of Albania is historically Muslim, the majority is non-practicing. Turkey and Tunisia are countries with overwhelmingly Muslim populations that enforce secularist practices by law. In the former USSR republics, a prohibition against polygamy has been inherited from Soviet Law. In the 21st century, a revival of the practice of polygamy in the Muslim World has contributed to efforts to re-establish its legality and legitimacy in some countries and communities where it is illegal.

Proposals have been made to re-legalize polygamy in other ex-Soviet Muslim republics, such as Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan.[72]

The original wife (or legal wife) was referred to as the 正室 zhèngshì /정실 (main room) both in China, Japan and Korea. 大婆 dàpó ("big woman/big wife") is the slang term. Both terms indicate the orthodox nature and hierarchy. The official wife was called "big mother" (大媽 dàmā), mother or aunt. The child of the concubine addressed the big mother as "aunt".

The written word for the second woman was 側室 cèshì /측실 and literally means "she who occupied the side room". This word was also used in both Korea and Japan. They were also called 妾 qiè/첩 in China and Korea. The common terms referring to the second woman, and the act of having the second woman respectively, are 二奶 (èrnǎi), literally "the second wife".

India

Polygamy in India is, in general, prohibited and the vast majority of marriages are legally monogamous. Polygyny among Christians was banned in the late 19th century, while The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 banned polygyny for Hindus. Currently, polygyny is only allowed among Muslims; but it is strongly discouraged by public policy. Muslims are subject to the terms of The Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act of 1937, interpreted by the All India Muslim Personal Law Board. Prevalence of polygyny in India is very low: among married women, only 1.68% of Hindus, 2.45% of Muslims, 2.16% of Christians, and 1.16% of other religions live in polygynous marriages.[73]

China

In mainland China, polygamy is illegal under Civil code passed in 2020. This replaced a similar 1950 and 1980 prohibition.[74]

Polygyny where wives are of equal status had always been illegal in China, and had been considered a crime in some dynasties. In family laws from Tang to Qing Dynasties, the status of a wife, concubines and maid-mistresses couldn't be altered.[75] However, concubinage was supported by law until the end of the Qing/Ching dynasty of the imperial China (1911). In the past, Emperors could and often did have hundreds to thousands of concubines. Rich officials and merchants of the elite also took concubines in addition to legal wives. The first wife was the head or mother wife; other wives were under her headship if the husband was away. Concubines had a lower status than full wives, generally not being seen in public with their husband and not having rights to decisions in the house. Children from concubines were considered inferior to those of the wife and did not receive equal wealth/legacy from their father. However they were considered legitimate, therefore had many more rights to inheritance of status and wealth than illegitimate children conceived outside a marriage.

Polygamy was de facto widely practiced in the Republic of China from 1911 to 1949, before Kuomintang was defeated in the Civil War and retreated to Taiwan. Zhang Zongchang, a well-known warlord, notably declared he had three 'unknowns' - unknown number of rifles, unknown amount of money, and unknown number of concubines. 不知道自己有多少枪,不知道自己有多少钱,不知道自己有多少姨太太

Chinese men in Hong Kong could practice concubinage by virtue of the Qing Code. This ended with the passing of the Marriage Act of 1971. Kevin Murphy of the International Herald Tribune reported on the cross-border polygamy phenomenon in Hong Kong in 1995.[76] In a research paper of Humboldt University of Berlin on sexology, Doctor Man-Lun Ng estimated about 300,000 men in China have mistresses. In 1995, 40% of extramarital affairs in Hong Kong involved a stable partner.[77]

Period drama and historical novels frequently refer to the former culture of polygamy (usually polygyny). An example is the Wuxia novel The Deer and the Cauldron by Hong Kong writer Louis Cha, in which the protagonist Wei Xiaobao has seven wives (In new edition of the novel, Princess Jianning was assigned as the wife, while others are concubines).

Kyrgyzstan

A proposal to decriminalize polygamy was heard by the Kyrgyz parliament. It was supported by the Justice Minister, the country's ombudsman, and the Muslim Women's organization Mutakalim, which had gathered 40,000 signatures in favour of polygamy. But, on March 26, 2007, parliament rejected the bill. President Kurmanbek Bakiyev is known to oppose legalizing polygyny.[78][79] Despite his opposition, he legally has two wives: Tatyana, with whom he has two sons; and Nazgul Tolomusheva, who gave birth for son and daughter.[80]

Tajikistan

Due to an increase in the number of polygamous marriages, proposals were made in Tajikistan to re-legalize polygamy.[81] Tajik women who want to be second wives particularly support decriminalizing polygyny. Mukhiddin Kabiri, the Deputy Chairman of the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan, says that legislation is unlikely to stop the growth in polygyny. He criticizes the ruling élite for speaking out against the practice while taking more than one wife themselves.[82]

Yemen

Polgyny is legal. Yemen, a majority Muslim nation, follows Islamic tradition where polgyny is acceptable up to four wives only if the husband treats all wives justly. 7% of married women in Yemen are a part of polygamous relationship. Reports conducted in the country have shown that regions that are rural areas are more likely to have polygamous relationships than those in cities or coastal areas.[83]

Bosnia and Herzegovina

The Muslim communities of Bosnia and Herzegovina traditionally practiced polygamy but the practice was last observed in Cazinska Krajina in the early 1950s.[84] Although illegal in the country, polygamy is encouraged by certain religious circles, and the number of practitioners has increased. This trend appears linked with the advent of fundamentalist Wahhabism in the Balkans.[85]

The Bosniak population in neighbouring Raška, Serbia, has also been influenced by this trend in Bosnia. They have suggested creating an entire Islamic jurisdiction including polygamy, but these proposals have been rejected by Serbia. The top cleric, the Mufti of Novi Pazar, Muamer Zukorlić, has taken a second wife.[86]

Russia

Factual polygamy and sexual relationships with several adult partners are not punishable in accordance with current revisions of Criminal Code of Russia and Code of the Russian Federation on Administrative Offenses. But multiple marriage can't be registered and officially recognised by Russian authorities because Family Code of Russia (section 14 and others) prohibits registration of marriage if one of person is in another registered marriage in Russia or another country. Polygamy is tolerated in predominantly Muslim republics such as Chechnya, Ingushetia, and Dagestan.[87]

Chechen politician Ramzan Kadyrov actively advocated for polygynous marriage to gain legal recognition. Muslim leaders such as Talgat Tadzhuddin[88] also pushed for the legal recognition of polygynous marriage.

Polygyny was legalized and documented in unrecognised Chechen Republic of Ichkeria but Russian authorities had annulled these polygynous marriages after they regained control over territory of Ichkeria. Later Ramzan Kadyrov, President of the Chechen Republic, has been quoted on radio as saying that the depopulation of Chechnya by war justifies legalizing polygamy.[89] Kadyrov has been supported by Nafigallah Ashirov, the Chairman of the Council of Grand Muftis of Russia, who has said that polygamy is already widespread among Muslim communities of the country.[90]

In Ingushetia in July, 1999 polygyny was officially recognised and allowed by edict of president of Ingushetia Ruslan Aushev and registration of polygyny marriages had been started allowing men to marry up to four wives as it relates to Muslim tradition. But this edict had been formally suspended soon by edict of President of Russia Boris Yeltsin. One year later this edict of Aushev had been cancelled by the Supreme Court of Ingushetia because of contradiction with Family Code of Russia.[91]

Although non-Muslim Russian populations have historically practiced monogamy, Russian politician Vladimir Zhirinovsky offered to legalize polygyny to encourage population growth and correct the demographic crisis of Russians. Zhirinovsky first proposed to legalize polygyny in 1993, after Kadyrov's declaration that he would introduce an amendment to legalize polygyny for all Russian citizens.[92][93]

United Kingdom

In the U.K, there are believed to be up to 20,000 polygamous marriages in Britain's Muslim's community,[94] even though bigamy is an offence.[95] All marriages that happen within the United Kingdom must be monogamous and meet the requirements of the relevant legislation to be perceived as legitimately substantial. For polygamous unions in the UK to be viewed as valid, the people must live in a country where a person is allowed to have more than one spouse and get married in a nation that permits it. There is evidence of unregistered polygamous marriages in the UK, performed through religious ceremonies, that are not recognized under UK law.[96] In May 2016, a cross-bench member of the British House of Lords Baroness Cox introduced the Arbitration and Mediation Services (Equality) Bill. This Bill would ensure that individuals in polygamous marriages and religiously recognized marriages not considered legal in the UK are informed that they could be without legal protection if they were caught by authorities.[96]

Chile

Polygyny has a long history among the Mapuche people of southern South America. Wives that share the same husband are often relatives, such as sisters, who live in the same community.[97] Having the same husband does not imply women belong to the same household.[97] Mapuche polygamy has no legal recognition in Chile.[97] This puts women who are not legally married to their husband at disadvantage to any legal wife in terms of securing inheritance.[97] It is thought that present-day polygamy is much less common than it once was, in particularly compared with the time before the Occupation of Araucanía (1861–1883) when Araucanía lost its autonomy.[97] Albeit chiefly rural Mapuche polygamy has also been reported in the low-income peripheral communes of Santiago.[98]

United States and Canada

Polygyny is illegal in the United States and Canada.

Mormon fundamentalism believes in the validity of selected fundamental aspects of Mormonism as taught and practiced in the nineteenth century. Fundamentalist Latter-Day Saints' teachings include plural marriage, a form of polygyny first taught by Joseph Smith, the founder of the Latter Day Saint movement.

In the 21st century, several sources have claimed as many as 60,000 fundamentalist Latter-day Saints in the United States,[99][100] with fewer than half of them living in polygamous households.[101] Others have suggested that there may be as few as 20,000 Mormon fundamentalists[102][103] with only 8,000 to 15,000 practicing polygamy.[104] The largest Mormon fundamentalist groups are the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (FLDS Church) and the Apostolic United Brethren (AUB). The FLDS Church is estimated to have 10,000 members residing in the sister cities of Hildale, Utah and Colorado City, Arizona; Eldorado, Texas; Westcliffe, Colorado; Mancos, Colorado; Creston and Bountiful, British Columbia; Pringle, South Dakota and Montana.[105]

Polygyny is also practiced by some Muslim immigrants to the US, especially those from Africa and Asia. NPR's All Things Considered estimated in 2008 that 50,000 to 100,000 American Muslims live in polygamous families.[106]

Religion

Hinduism

The Hindu scriptures acknowledge numerous occasions of polygyny; it was the norm among kings, the nobility and the extremely wealthy. Pandu, the father of the Pandavas in Mahabharata, had two wives Kunti and Madri. Many other personalities including Rama had only one wife, and while this was regarded as morally exemplary, polygyny remained customary and acceptable among Hindus. It was legally abolished for Hindus in India by the Hindu Marriage Act of 1955.

Judaism

Polygyny is not forbidden in the Old Testament and over 40 important figures had more than one wife, such as Esau[Genesis 26:34][28:6–9], Elkanah[1 Samuel 1:1–8], and Solomon[1 Kings 11:1–3]. Moses had three wives; Zipporah[Exodus 2: 21], the daughter of Hobab[Numbers 10: 291] and the "Cushite" woman.[Numbers 12: 1] .[lower-alpha 1] However, Deuteronomy 17:17 does state that the king shall not have too many wives.[107][108]

According to Michael Coogan, "[p]olygyny continued to be practiced well into the biblical period, and it is attested among Jews as late as the second century CE."[109] The incidence was limited, however, and it was likely largely restricted to the wealthy.[110] By the first century, both the expense and the practical problems associated with maintaining multiple wives were barriers to the practice, especially for the less wealthy.[111] Since the 11th century, Ashkenazi Jews have followed Rabbenu Gershom's ban on polygyny (except in rare circumstances).[112]

Some Mizrahi (Mideast) Jewish communities (particularly Yemenite Jews and Persian Jews) discontinued polygyny more recently, after they immigrated to countries where it was forbidden or illegal. Israel prohibits polygamy by law.[113][114] In practice, however, the law is loosely enforced, primarily to avoid interference with Bedouin culture, where polygyny is practiced.[115] Pre-existing polygynous unions among Jews from Arab countries (or other countries where the practice was not prohibited by their tradition and was not illegal) are not subject to this Israeli law. But Mizrahi Jews are not permitted to enter into new polygamous marriages in Israel. However polygamy may still occur in non-European Jewish communities that exist in countries where it is not forbidden, such as Jewish communities in Yemen and the Arab world.

Karaite Jews, who do not adhere to Rabbinic interpretations of the Torah, do not practice polygyny. Karaites interpret Leviticus 18:18 to mean that a man can only take a second wife if his first wife gives her consent[116] and Exodus 21:10 to mean that a man can only take a second wife if he is capable of maintaining the same level of marital duties due to his first wife: namely, food, clothing, and sexual gratification.

Christianity

Polygamy is not forbidden in the Old Testament. The New Testament is largely silent on polygamy, however, some point to Jesus's repetition of the earlier scriptures, noting that a man and a wife "shall become one flesh".[117] However, some look to Paul's writings to the Corinthians: "Do you not know that he who is joined to a prostitute becomes one body with her? For, as it is written, 'The two will become one flesh.'" Supporters of polygamy claim this indicates that the term refers to a physical, rather than spiritual, union.[118]

Most Christian theologians argue that in Matthew 19:3-9 and referring to Genesis 2:24 Jesus explicitly states a man should have only one wife:

Have ye not read, that he which made them at the beginning made them male and female, And said, For this cause shall a man leave father and mother, and shall cleave to his wife: and they twain shall be one flesh?

Jesus also tells the Parable of the Ten Virgins going to meet the bridegroom, without making any explicit criticism or other comment on the practice of polygamy.

The Bible states in the New Testament that polygamy should not be practiced by certain church leaders. 1 Timothy states that certain Church leaders should have but one wife: "A bishop then must be blameless, the husband of one wife (mias gunaikos andra, lit. one-woman man), vigilant, sober, of good behavior, given to hospitality, apt to teach" (chapter 3, verse 2; see also verse 12 regarding deacons having only one wife). Similar counsel is repeated in the first chapter of the Epistle to Titus.[119]

Periodically, Christian reform movements that have aimed at rebuilding Christian doctrine based on the Bible alone (sola scriptura) have at least temporarily accepted polygyny as a Biblical practice. For example, during the Protestant Reformation, in a document referred to simply as "Der Beichtrat" (or "The Confessional Advice" ),[120] Martin Luther, whose reformation caused a schism in the Western Christian Church leading to the formation of the Lutheran Church, granted the Landgrave Philip of Hesse, who, for many years, had been living "constantly in a state of adultery and fornication",[121] a dispensation to take a second wife. The double marriage was to be done in secret, however, to avoid public scandal.[122] Some fifteen years earlier, in a letter to the Saxon Chancellor Gregor Brück, Luther stated that he could not "forbid a person to marry several wives, for it does not contradict Scripture." ("Ego sane fateor, me non posse prohibere, si quis plures velit uxores ducere, nec repugnat sacris literis.")[123]

"On February 14, 1650, the parliament at Nürnberg decreed that, because so many men were killed during the Thirty Years' War, the churches for the following ten years could not admit any man under the age of 60 into a monastery. Priests and ministers not bound by any monastery were allowed to marry. Lastly, the decree stated that every man was allowed to marry up to ten women. The men were admonished to behave honorably, provide for their wives properly, and prevent animosity among them."[124][125][126][127][128][129]

As such, the Lutheran World Federation hosted a regional conference in Africa, in which the acceptance of polygynists and their wives into full membership by the Lutheran Church in Liberia was defended as being permissible.[130] The Lutheran Church in Liberia, while permitting men to retain their wives from marriages prior to being received into the Church, does not permit polygynists who have become Christians to marry more wives after they have received the sacrament of Holy Baptism.[131] Evangelical Lutheran missionaries in Maasai also tolerate the practice of polygyny and in Southern Sudan, some polygynists are becoming Lutheran Christians.[132]

On the other hand, the Roman Catholic Church criticizes polygyny in the Catechism of the Catholic Church. Under paragraph 2387 of "Other offenses against the dignity of marriage" of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, it states "is not in accord with the moral law." Additionally, paragraph 1645 of "The Goods and Requirements of Conjugal Love" states "The unity of marriage, distinctly recognized by our Lord, is made clear in the equal personal dignity which must be accorded to husband and wife in mutual and unreserved affection. Polygamy is contrary to conjugal love which is undivided and exclusive."[133] There are small numbers of Roman Catholic theologians that claim polygyny can be an authentic form of marriage in certain regions such as Africa.[134]

In Sub-Saharan Africa, there has often been a tension between the Western Christian insistence on monogamy and the traditional practice of polygamy. In some instances in recent times there have been moves for accommodation; in other instances, churches have resisted such moves strongly. African Independent Churches have sometimes referred to those parts of the Old Testament that describe polygamy in defending the practice.

Islam

Under Islamic marital jurisprudence, Muslim men are allowed to practice polygyny, that is, they can have more than one wife at the same time, up to a total of four. Polyandry, the practice of a woman having more than one husband, is not permitted.

Based on verse 30:21 of Quran the ideal relationship is the comfort that a couple find in each other's embrace:

And one of His signs is that He created for you spouses from among yourselves so that you may find comfort in them. And He has placed between you compassion and mercy. Surely in this are signs for people who reflect.

The polygyny that is allowed in the Quran is for special situations; however, it advises monogamy if a man fears he can't deal justly with them. This is based on verse 4:3 of Quran which says:

If you fear you might fail to give orphan women their ˹due˺ rights ˹if you were to marry them˺, then marry other women of your choice—two, three, or four. But if you are afraid you will fail to maintain justice, then ˹content yourselves with˺ one or those ˹bondwomen˺ in your possession. This way you are less likely to commit injustice.

There are strict requirements to marrying more than one woman, as the man must treat them equally financially and in terms of support given to each wife, according to Islamic law.[137]

Muslim women aren't allowed to marry more than one husband at once. However, in the case of a divorce or their husbands' death they can remarry after the completion of Iddah, as divorce is legal in Islamic law. A non-Muslim woman who flees from her non-Muslim husband and accepts Islam can remarry without divorce from her previous husband, as her marriage with non-Muslim husband is Islamically dissolved on her fleeing. A non-Muslim woman captured during war by Muslims, can also remarry, as her marriage with her non-Muslim husband is Islamically dissolved at capture by Muslim soldiers. This permission is given to such women in verse 4:24 of Quran. The verse also emphasizes on transparency, mutual agreement and financial compensation as prerequisites for matrimonial relationship as opposed to prostitution; it says:

Also ˹forbidden are˺ married women—except ˹female˺ captives in your possession. This is God's commandment to you. Lawful to you are all beyond these—as long as you seek them with your wealth in a legal marriage, not in fornication. Give those you have consummated marriage with their due dowries. It is permissible to be mutually gracious regarding the set dowry. Surely God is All-Knowing, All-Wise.

Muhammad was monogamously married to Khadija, his first wife, for 25 years, until she died. After her death, he married multiple women, mostly widows,[139] for social and political reasons.[140] He had a total of nine wives, but not all at the same time, depending on the sources in his lifetime. The Qur'an does not give preference in marrying more than one wife. One reason cited for polygyny is that it allows a man to give financial protection to multiple women, who might otherwise not have any support (e.g. widows).[141] However, the wife can set a condition, in the marriage contract, that the husband cannot marry another woman during their marriage. In such a case, the husband cannot marry another woman as long as he is married to his wife.[142] According to traditional Islamic law, each of those wives keeps their property and assets separate; and are paid mahar and maintenance separately by their husband. Usually the wives have little to no contact with each other and lead separate, individual lives in their own houses, and sometimes in different cities, though they all share the same husband.

In most Muslim-majority countries, polygyny is legal with Kuwait being the only one where no restrictions are imposed on it. The practice is illegal in Muslim-majority Turkey, Tunisia, Albania, Kosovo and Central Asian countries.[143][144][145][146]

Countries that allow polygyny typically also require a man to obtain permission from his previous wives before marrying another, and require the man to prove that he can financially support multiple wives. In Malaysia and Morocco, a man must justify taking an additional wife at a court hearing before he is allowed to do so.[147] In Sudan, the government encouraged polygyny in 2001 to increase the population.[148]

Buddhism

Buddhism does not regard marriage as a sacrament - it is a secular affair, and normally Buddhist monks do not participate in it (though in some sects priests do marry). Hence marriage receives no religious sanction.[149] Forms of marriage, in consequence, vary from country to country.

Thailand legally recognized polygamy until 1955. Myanmar outlawed polygyny from 2015. In Sri Lanka, polyandry was legal in the Kingdom of Kandy, but outlawed by British after conquering the kingdom in 1815.[149] When the Buddhist texts were translated into Chinese, the concubines of others were added to the list of inappropriate partners. Polyandry in Tibet was common traditionally, as was polygyny, and having several wives or husbands was never regarded as having sex with inappropriate partners.[150]

The Parabhava Sutta states that "a man who is not satisfied with one woman and seeks out other women is on the path to decline". Other fragments in the Buddhist scripture seem to treat polygamy unfavorably, leading some authors to conclude that Buddhism generally does not approve of it[151] or alternatively regards it as a tolerated, but subordinate, marital model.[152]

In nature

In zoology the term polygyny is used for a pattern of mating in which a male animal has more than one female mate in a breeding season.[153] Males get their mates by defending the females directly or holding resources that the females want and need. This is known as resource defense polygyny and males of the bee species Anthidium manicatum (also known as the European wool carder bee) exhibit this behavior. Males claim patches of floral plants, ward off conspecific males and other resource competitors, and mate with the multiple females who forage in their territories.[154] Males of many species attract females to their territory by either gathering in a lek or going out in search of dispersed females. In polygyny relationships in animals, the female is the one who provides most of the parental care for the offspring.[155]

Polygyny in eusocial insects means that some insects living in colonies have not only one queen, but several queens.[153] Solitary species of insects take part in this practice in order to maximize their reproductive success of the widely dispersed females, such as the bee species Anthidium maculosum.[156] Insects such as red flour beetles use polygyny to reduce inbreeding depression and thus maximize reproductive success.

There is primary polygyny (several queens join to found a new colony, but after the hatching of the first workers the queens fight each other until only one queen survives and the colony becomes monogynous) and secondary polygyny (a well-established colony continues to have several queens).

See also

Notes

- Translated as the Ethiopian woman in the Authorised Version.[Numbers 12: 1]

- A Greek–English Lexicon, Liddell & Scott, s.v. γυνή

- Clignet, R., Many Wives, Many Powers, Northwestern University Press, Evanston (1970), p. 17.

- Dalton, John; Leung, Tin Cheuk (2014). "Why Is Polygyny More Prevalent in Western Africa? An African Slave Trade Perspective" (PDF). Economic Development and Cultural Change. 62 (4): 601–604. doi:10.1086/676531. S2CID 224797897. SSRN 1848183 – via Business Source Complete.

- "African polygamy: Past and present". 2013-11-09.

- "LDS splinter groups growing | the Salt Lake Tribune".

- "Canadian polygamists found guilty". BBC News. 2017-07-25.

- Boserup, Esther. (1970). Woman's Role in Economic Development, London, England & Sterling, VA: Cromwell Press, Trowbridge

- Guyer, Jane. (1991). "Female Farming in Anthropology and African History”. Gender at the Crossroads of Knowledge: Feminist Anthropology in the postmodern Era. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. p. 260-261.

- Andrea Cornwall (2005). Readings in Gender in Africa. Indiana University Press. pp. 103–110. ISBN 978-0-253-34517-2.

- Boserup Esther. (1970). Woman's Role in Economic Development, London, England & Sterling, Virginia: Cromwell Press, Trowbridge.

- Boserup Esther. (1970). Women's role in economic development. London, England & Sterling, VA: Cromwell Press, Trowbridge.

- Goody, Jack (1976). Production and Reproduction: A Comparative Study of the Domestic Domain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 27–9.

- Goody, Jack. Polygyny, Economy and the Role of Women. In The Character of Kinship. London: Cambridge University Press, 1973, p. 180–190.

- White, Douglas; Burton, Michael (1988). "Causes of Polygyny: Ecology, Economy, Kinship, and Warfare". American Anthropologist. 90 (4): 871–887 [884]. doi:10.1525/aa.1988.90.4.02a00060.

- White, Douglas; Burton, Michael (1988). "Causes of Polygyny: Ecology, Economy, Kinship, and Warfare". American Anthropologist. 90 (4): 871–887 [873]. doi:10.1525/aa.1988.90.4.02a00060.

- White DR, Burton ML, Dow MM (December 1981). "Sexual Division of Labor in African Agriculture: A Network Autocorrelation Analysis". American Anthropologist. 83 (4): 824–849. doi:10.1525/aa.1981.83.4.02a00040.

- Fenske, James (November 2012), AFRICAN POLYGAMY: PAST AND PRESENT (PDF), Centre for the Study of African Economies, University of Oxford, pp. 1–30

- Timeas, Ian and Reyner, Angela. "Polygynists and Their Wives in Sub-Saharan Africa: an Analysis of Five Demographic and Health Surveys". Population Studies 52.2 (1998)

- Gwako, Edwins Laban. "Polygamy Among the Logoli of Western Kenya". Anthropos 93.4 (1998). Web.

- Low B (1088) Measures of polygyny in humans. Curr Anthropol 29: 189–194.B.

- Murdock GP (1981) Atlas of World Cultures. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburgh Press

- Anderson, M. J.; Dixson, A. F. (2002). "Sperm competition: motility and the midpiece in primates". Nature 416: 496

- Dixson, A. L.; Anderson, M. J. (2002). "Sexual selection, seminal coagulation and copulatory plug formation in primates". Folia Primatol (Basel) 73: 63–69.

- Harcourt, A. H.; Harvey, P. H.; Larson, S. G.; Short, R.V. (1981). "Testis weight, body weight and breeding system in primates". Nature 293: 55–57

- Porter, Jonathan (2015). "L'amour for four: polygyny, polyamory, and the state's compelling economic interest in normative monogamy" (PDF). Emory Law Journal. 64: 2121.

- Jacoby, Hanan (1995). "The Economics of Polygyny in Sub-Saharan Africa: Female Productivity and the Demand for Wives in Côte d'Ivoire". Journal of Political Economy. 103 (5): 942–943. doi:10.1086/262009. S2CID 153376774.

- Kammeyer, Kenneth (1975). Confronting the issues: sex roles, marriage, and the family. p. 117.

- Baber, Ray (1939). Marriage and the Family. p. 38.

- Thomas, Paul (1964). Indian Women Through the Ages: A Historical Survey of the Position of Women and the Institutions of Marriage and Family in India from Remote Antiquity to the Present Day. P. Thomas. p. 206.

- Dardess, George (2005). Meeting Islam: A Guide for Christians. p. 99.

- Balon, R (2015). "Is Infidelity Biologically Determined?". European Psychiatry. 30: 72. doi:10.1016/S0924-9338(15)30061-4.

- Hrala, Josh. "Vikings Might Have Started Raiding Because There Was a Shortage of Single Women". ScienceAlert. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 2019-07-19.

- Choi, Charles Q.; November 8, Live Science Contributor |; ET, 2016 09:07am. "The Real Reason for Viking Raids: Shortage of Eligible Women?". Live Science. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 2019-07-21.

- "Sex Slaves – The Dirty Secret Behind The Founding Of Iceland". All That's Interesting. 2018-01-16. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 2019-07-22.

- "Kinder, Gentler Vikings? Not According to Their Slaves". National Geographic News. 2015-12-28. Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 2019-08-02.

- David R. Wyatt (2009). Slaves and Warriors in Medieval Britain and Ireland: 800–1200. Brill. p. 124. ISBN 978-90-04-17533-4.

- Viegas, Jennifer (2008-09-17). "Viking Age triggered by shortage of wives?". msnbc.com. Archived from the original on 23 July 2019. Retrieved 2019-07-21.

- Knapton, Sarah (2016-11-05). "Viking raiders were only trying to win their future wives' hearts". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 1 August 2019. Retrieved 2019-08-01.

- "New Viking Study Points to "Love and Marriage" as the Main Reason for their Raids". The Vintage News. 2018-10-22. Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 2019-08-02.

- Karras, Ruth Mazo (1990). "Concubinage and Slavery in the Viking Age". Scandinavian Studies. 62 (2): 141–162. ISSN 0036-5637. JSTOR 40919117.

- Poser, Charles M. (1994). "The dissemination of multiple sclerosis: A Viking saga? A historical essay". Annals of Neurology. 36 (S2): S231–S243. doi:10.1002/ana.410360810. ISSN 1531-8249. PMID 7998792. S2CID 36410898.

- Andrea Dolfini; Rachel J. Crellin; Christian Horn; Marion Uckelmann (2018). Prehistoric Warfare and Violence: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. Springer. p. 349. ISBN 978-3-319-78828-9.

- Ethnographic Atlas Codebook Archived 2012-11-18 at the Wayback Machine derived from George P. Murdock’s Ethnographic Atlas recording the marital composition of 1,231 societies from 1960 to 1980.

- "Polygamy is the key to a long life", New Scientist, 19 August 2008

- Nettle, D. (2009). "Ecological influences on human behavioural diversity: A review of recent findings". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 24 (11): 618–24. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2009.05.013. PMID 19683831.

- "The perils of polygamy: The link between polygamy and war". The Economist. 19 December 2017. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- Koos, Carlo; Neupert-Wentz, Clara (July 23, 2019). "Polygynous Neighbors, Excess Men, and Intergroup Conflict in Rural Africa". Journal of Conflict Resolution. SAGE Publications. 64 (2–3): 402–431. doi:10.1177/0022002719859636. ISSN 0022-0027.

- Harmon, Vanessa; Mujkic, Edin; Kaukinen, Catherine; Weir, Henriikka (2018). "Causes & Explanations of Suicide Terrorism: A Systematic Review". Homeland Security Affairs. NPS Center for Homeland Defense and Security. 25.

- Gibson, Kyle R. (2011). "The Roles of Operational Sex Ratio and Young-Old Ratio in Producing Suicide Attackers". University of Utah.

- Pape, Robert (2003). "The Strategic Logic of Suicide Terrorism" (PDF). American Political Science Review. Cambridge University Press. 97 (3): 343–361. doi:10.1017/S000305540300073X. hdl:1811/31746.

- "U.S. study draws portrait of Iraq bombers". USA Today. Gannett. March 15, 2008. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- Hudson, Valerie M.; Thayer, Bradley (2010). "Sex and the Shaheed: Insights from the Life Sciences on Islamic Suicide Terrorism". International Security. MIT Press. 34 (4): 48–53. JSTOR 40784561.

- Exposito, Natali (2017). "The Negative Impact of Polygamy on Women and Children in Mormon and Islamic Cultures". Seton Hall University Law School Student Scholarship. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017.

- Al-Krenawi, Alean; Graham, John (2011). "A Comparison Study of Psychological Family Function Marital Satisfaction of Polygamous and Monogamous women in Jordan". Community Mental Health Journal. 47 (5): 594–602. doi:10.1007/s10597-011-9405-x. PMID 21573772. S2CID 11063695.

- Bove, Riley; Valeggia, Claudia (2009). "Polygyny and Women's Health in Sub-Saharan Africa". Social Science and Medicine. 68 (1): 21–29. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.045. PMID 18952335.

- Shepard, L.D. (2013). "The impact of polygamy on women's mental health: a systematic review". Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. 2 (1): 47–62. doi:10.1017/S2045796012000121. PMC 6998378. PMID 22794315.

- Lee, Gary R. (1982). "Structural Variety in Marriage". Family Structure and Interaction: A Comparative Analysis (2nd, revised ed.). University of Minnesota Press. pp. 91–92.

- Ukaegbu, Alfred O. (1977). "Fertility of Women in Polygynous Unions in Rural Eastern Nigeria". Journal of Marriage and Family. 39 (2): 397–404. doi:10.2307/351134. ISSN 0022-2445. JSTOR 351134.

- Ware, Helen (1979). "Polygyny: Women's Views in a Transitional Society, Nigeria 1975". Journal of Marriage and Family. 41 (1): 185–195. doi:10.2307/351742. ISSN 0022-2445. JSTOR 351742.

- Reniers, Georges; Tfaily, Rania (2012-08-01). "Polygyny, Partnership Concurrency, and HIV Transmission in Sub-Saharan Africa". Demography. 49 (3): 1075–1101. doi:10.1007/s13524-012-0114-z. ISSN 1533-7790. PMID 22661302. S2CID 207472013.

- Mwale, Biziwick (September 2002). "HIV/AIDS in Malawi". Malawi Medical Journal : The Journal of Medical Association of Malawi. 14 (2): 2–3. ISSN 1995-7262. PMC 3346002. PMID 27528929.

- Jr, John Witte. "Why Two in One Flesh? The Western Case for Monogamy over Polygamy | Emory University School of Law | Atlanta, GA". Emory University School of Law. Retrieved 2019-11-24.

- Ifediora, John (2016). "Polygamy As Further Subjugation Of African Women, And National Economies". CASADE: 1.

- Boserup, Ester. 1970. "The Economics of Polygamy". In Women's Role in Economic Development, edited by Ester Boserup, 47. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Wiesner-Hanks, Merry E. Gender in History: Global Perspectives. 2nd ed., Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. (Page 34)

- Laban Moogi Gwako, Edwins (1998). "Polygyny among the Logoli of Western Kenya". Anthropos. 93 (4/6): 331–348. JSTOR 40464835.

...encoraged their husbands to marry other wives so that they may engage themselves and bestow their affection upon the co-wives' children.

- "Figures 18 and 2.10. Social institutions and gender index (SIGI)". doi:10.1787/888933163273.

- Lamloum, Olfa (2010), "Islamonline. Jeux et enjeux d'un média " post-islamiste " déterritorialisé", Médias et islamisme, Presses de l’Ifpo, pp. 45–62, doi:10.4000/books.ifpo.1369, ISBN 978-2-35159-172-7

- Moosa, N (2009-09-24). "Polygynous Muslim Marriages in South Africa: Their Potential Impact on the Incidence of HIV/AIDS". Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal/Potchefstroomse Elektroniese Regsblad. 12 (3). doi:10.4314/pelj.v12i3.46271. ISSN 1727-3781.

- "Acceptance of Polygamy Slowly Changes in Muslim Africa". Voice of America. 12 March 2007. Archived from the original on 2009-05-07. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- Mwareya, Ray (5 July 2016). "Widows without sons in Mozambique accused of sorcery and robbed of land". Reuters. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

Although polygamy is prohibited in Mozambique there is no punishment. Across the country nearly a third of married women are thought to be in polygamous marriages, according to a NORAD survey.

- Saidazimova, Gulnoza (February 4, 2005), "Polygamy hurts - in the pocket", Asia Times Online

- http://paa2011.princeton.edu/papers/111406

- "Marriage Law of the People's Republic of China". www.lawinfochina.com.

- "毋以妾为妻". douban.com. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- Archived February 10, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "Hong Kong" Archived 2006-11-05 at the Wayback Machine, The International Encyclopedia of Sexuality

- "Kyrgyzstan: Debate On Legalized Polygamy Continues", Radio Liberty, Radio Free Europe

- "Kyrgyz Lawmakers Reject Decriminalizing Polygamy". rferl.org. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- "Максим Бакиев стрелял в ногу отцу за то, что тот взял другую жену » Ушактар » Gezitter.org - Чтобы понимали..." gezitter.org. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- "Central Asia: Increase In Polygamy Attributed To Economic Hardship, Return To Tradition", EurasiaNet.org

- "Institute for War and Peace Reporting". iwpr.net. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- Polygamy in Yemen Archived 2009-03-25 at the Wayback Machine

- "Bosnian Americans" - History, Modern era, The first bosnians in America, Every Culture

- "Emissaries of Militant Islam Make Headway in Bosnia - - on B92.net". b92.net. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- "Bosnia and Herzegovina: The veil comes down, again - Women Reclaiming and Redefining Cultures". wluml.org. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- Osborn, Andrew (2006-01-14). "War-ravaged Chechnya needs polygamy, says its leader". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 2006-01-17.

- Rosbalt (13 January 2006). "Верховный муфтий России - за многоженство [Chief Mufti of Russia supports polygamy] (in Russian)". Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- "I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do: The Economic Case for Polygamy", Pilegesh.org blog

- "Inter Press Service - News and Views from the Global South". ipsnews.net. Archived from the original on 12 February 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- "Лентапедия. Биография Руслана Аушева" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2011-11-01. Retrieved 2009-12-08.

- Vladimir Zhirinovsky Op-Ed: "When One Wife Is Not Enough", The St. Petersburg Times

- "Polygamy proposal for Chechen men". BBC News. 2006-01-13.

- "The Men with many wives" by Channel 4

- Offences Against the Person Act 1861

- Fairbairn, Catherine; Kennedy, Steven; Thurley, Djuna; Wilkins, Hannah (2018-11-22). "Polygamy".

- Rausell, Fuencis (June 1, 2013). "La poligamia pervive en las comunidades indígenas del sur de Chile". La Información (in Spanish). Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- Millaleo Hernández, Ana Gabriel (2018). Poligamia mapuche / Pu domo ñi Duam (un asunto de mujeres): Politización y despolitización de una práctica en relación a la posición de las mujeres al interior de la sociedad mapuche (PDF) (PhD thesis) (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: University of Chile. p. 133.

- Martha Sonntag Bradley, "Polygamy-Practicing Mormons" in J. Gordon Melton and Martin Baumann (eds.) (2002). Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia 3:1023–1024.

- Dateline NBC, 2001-01-02.

- Ken Driggs, "Twentieth-Century Polygamy and Fundamentalist Mormons in Southern Utah", Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, Winter 1991, pp. 46–47.

- Irwin Altman, "Polygamous Family Life: The Case of Contemporary Mormon Fundamentalists", Utah Law Review (1996) p. 369.

- D. Michael Quinn, "Plural Marriage and Mormon Fundamentalism" Archived 2011-06-13 at the Wayback Machine, Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 31(2) (Summer 1998): 1–68, accessed 27 March 2009.

- Stephen Eliot Smith, "'The Mormon Question' Revisited: Anti-Polygamy Laws and the Free Exercise Clause", LL.M. thesis, Harvard Law School, 2005.

- "The Primer" Archived 2005-01-11 at the Wayback Machine - Helping Victims of Domestic Violence and Child Abuse in Polygamous Communities. A joint report from the offices of the Attorneys General of Arizona and Utah.

- Barbara Bradley Hagerty, "Some Muslims in US Quietly Engage in Polygamy", NPR, 2008-05-27.

- Judaica Press Complete Tanach, Devarim - Chapter 17 from Chabad.org.

- The king's behavior is condemned by Prophet Samuel in 1 Samuel 8.

- Coogan, Michael (October 2010). God and Sex. What the Bible Really Says (1st ed.). New York, Boston: Twelve. Hachette Book Group. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-446-54525-9. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- du Plessis, I. (1998). "The social and economic life of the Jewish people in Palestine in the time of the New Testament", In A. du Toit (Ed.). Vol. 2: The New Testament Milieu (A. du Toit, Ed.). Guide to the New Testament. Halfway House: Orion Publishers.

- Theological dictionary of the New Testament. 1964– (G. Kittel, G. W. Bromiley & G. Friedrich, Ed.) (electronic ed.). Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. Entry on γυνή

- Frequently asked questions, Judaism and Polygamy.

- Penal Law Amendment (Bigamy) Law, 5719-1959.

- Shifman, P. (1 January 1978). "The English Law of Bigamy in a Multi-Confessional Society: The Israel Experience". The American Journal of Comparative Law. 26 (1): 79–89. doi:10.2307/839776. JSTOR 839776.

- "Victims of polygamy", Haaretz

- Keter Torah on Leviticus, pp. 96–97.

- Genesis 2:24, Matthew 19:3–6

- 1 Corinthians 6:16

- The Digital Nestle-Aland lists only one manuscript (P46) as source of the verse, while nine other manuscripts have no such verse, cf. http://nttranscripts.uni-muenster.de/AnaServer?NTtranscripts+0+start.anv

- Letter to Philip of Hesse, 10 December 1539, De Wette-Seidemann, 6:238–244

- Michelet, ed. (1904). "Chapter III: 1536–1545". The Life of Luther Written by Himself. Bohn's Standard Library. Translated by Hazlitt, William. London: George Bell and Sons. p. 251.

- James Bowling Mozley Essays, Historical and Theological 1:403–404 Excerpts from Der Beichtrat

- Letter to the Chancellor Gregor Brück, 13 January 1524, De Wette 2:459.

- Larry O. Jensen, A Genealogical Handbook of German Research (Rev. Ed., 1980) p. 59.

- Joseph Alfred X. Michiels, Secret History of the Austrian Government and of its Systematic Persecutions of Protestants (London: Chapman and Hall, 1859) p. 85 (copy at Google Books), the author stating that he is quoting from a copy of the legislation.

- William Walker Rockwell, Die Doppelehe des Landgrafen Philipp von Hessen (Marburg, 1904), p. 280, n. 2 (copy at Google Books), which reports the number of wives allowed was two.

- Leonhard Theobald, "Der angebliche Bigamiebeschluß des fränkischen Kreistages" ["The So-called Bigamy Decision of the Franconian Kreistag"], Beitrage zur Bayerischen kirchengeschichte [Contributions to Bavarian Church History] 23 (1916 – bound volume dated 1917) Erlangen: 199–200 (Theobald reporting that the Franconian Kreistag did not hold session between 1645 and 1664, and that there is no record of such a law in the extant archives of Nürnberg, Ansbach, or Bamberg, Theobald believing that the editors of the Fränkisches Archiv must have misunderstood a draft of some other legislation from 1650).

- Alfred Altmann, "Verein für Geschichte der Stadt Nürnburg," Jahresbericht über das 43 Vereinsjahr 1920 [Annual Report for the 43rd Year 1920 of the Historical Society of the City of Nuremberg] (Nürnberg 1920): 13–15 (Altmann reporting a lecture he had given discussing the polygamy permission said to have been granted in Nuremberg in 1650, Altmann characterizing the Fränkisches Archiv as "merely a popular journal, not an edition of state documents," and describing the tradition as "a literary fantasy").

- See Heinrich Christoph Büttner, Johann Heinrich Keerl, und Johann Bernhard Fischer. Fränkisches Archiv, herausgegeben. I Band. 1790. (at p. 155) (setting forth a 1790 printing of the legislation).

- Deressa, Yonas (1973). The Ministry of the Whole Person. Gudina Tumsa Foundation. p. 350.

- Kilbride, Philip Leroy; Page, Douglas R. (2012). Plural Marriage for Our Times: A Reinvented Option?. ABC-CLIO. p. 188. ISBN 9780313384783.

- Mlenga, Moses (13 January 2016). Polygamy in Northern Malawi: A Christian Reassessment. Mzuni Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 9789996045097.

- "CATECHISM OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH". Vatican. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- "The Ratzinger report: an exclusive interview on the state of the Church Pope Benedict XVI, Vittorio Messori", p. 195, Ignatius Press, 1985, ISBN 0-89870-080-9

- [Quran 30:21]

- Quran 4:3

- Ratno Lukito. Legal Pluralism in Indonesia: Bridging the Unbridgeable. Routledge. p. 81.

- Quran 4:24

- "Prophet Muhammad and polygyny", IslamWeb.

- Sahar El-Nadi, "Why Did the Prophet Have So Many Wives?," OnIslam.net

- "IslamWeb". IslamWeb. 7 February 2002. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- "ahlalhdeeth". ahlalhdeeth. 12 September 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- Nurmila, Nina (10 June 2009). Women, Islam and Everyday Life: Renegotiating Polygamy in Indonesia. Routledge. ISBN 9781134033706. Retrieved 10 December 2016 – via Google Books.

- Maike Voorhoeve (31 January 2013). "Tunisia: Protecting Ben Ali's Feminist Legacy". Think Africa Press. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- Kudat, Ay?e; Peabody, Stan; Keyder, Ça?lar (1 January 2000). Social Assessment and Agricultural Reform in Central Asia and Turkey. World Bank Publications. ISBN 9780821346785. Retrieved 10 December 2016 – via Google Books.

- "LES EXPERTS DU CEDAW S'INQUIÈTENT DE LA PERSISTANCE DE STÉRÉOTYPES SEXISTES ET DE LA SITUATION DES MINORITÉS EN SERBIE". United Nations. May 16, 2007. Retrieved February 3, 2016.

- Modern Muslim societies. 2010. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-7614-7927-7.

- "Omar Hassan al-Bashir, has urged Sudanese men to take more than one wife to increase the population". BBC News. 15 August 2001. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- "Accesstoinsight.org". Accesstoinsight.org. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- Berzin, Alexander (7 October 2010). "Buddhist Sexual Ethics: Main Issues". Study Buddhism. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016.

- The Ethics of Buddhism, Shundō Tachibana, Routledge, 1992, ISBN 978-0-7007-0230-5

- An introduction to Buddhist ethics: foundations, values, and issues, Brian Peter Harvey, Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0-521-55640-8

- Anon. "Polygyny". dictionary.com. Dictionary.com. Retrieved 22 October 2015.