Hungarian nobility

The Hungarian nobility consisted of a privileged group of people, most of whom owned landed property, in the Kingdom of Hungary. Initially, a diverse category of people were mentioned as noblemen, but from the late 12th century only the high-ranking royal officials were regarded as noble. Most aristocrats claimed a late-9th-century Magyar leader for their ancestor; others were descended from foreign knights; and local Slavic chiefs were also integrated in the nobility. Less illustrious individuals, known as castle warriors, also held landed property and served in the royal army. Most privileged laymen called themselves royal servants to emphasize their direct contact to the monarchs from the 1170s. The Golden Bull of 1222 enacted their liberties, especially their tax-exemption and the limitation of their military obligations. From the 1220s, the royal servants were associated with the nobility and the highest-ranking officials were known as barons of the realm. Only those who owned allods – lands free of obligations – were regarded true noblemen, but other privileged groups of landowners, known as conditional nobles, also existed.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Hungary |

|

|

|

Simon of Kéza was the first to claim, in the 1280s, that the noblemen held real authority in the kingdom. The counties developed into institutions of noble autonomy and the nobles' delegates attended the Diets (or parliaments). The wealthiest barons built stone castles which enabled them to control vast territories, but royal authority was restored in the early 14th century. Louis I of Hungary introduced an entail system and enacted the principle of "one and the selfsame liberty" of all noblemen. Actually, legal distinctions between true noblemen and conditional nobles prevailed, and the most powerful nobles employed lesser noblemen as their familiares (or retainers). According to customary law, only males inherited noble estates, but the kings could "promote a daughter to a son", authorizing her to inherit her father's lands. Noblewomen who had married a commoner could also claim their inheritance – the daughters' quarter – in land.

The monarchs granted hereditary titles and the poorest nobles lost their tax-exemption from the middle of the 15th century, but the Tripartitum – a frequently cited compilation of customary law – maintained the notion of all noblemen's equality. In the early modern period, Hungary was divided into three parts – Royal Hungary, Transylvania and Ottoman Hungary – due to the expansion of the Ottoman Empire in the 1570s. The princes of Transylvania supported the noblemen's fight against the Habsburg kings in Royal Hungary, but they prevented the Transylvanian noblemen from challenging their authority. Ennoblement of whole groups of people was not unusual in the 17th century. After the Diet was divided into two chambers in Royal Hungary in 1608, noblemen with a hereditary title had a seat in the Upper House, other nobles sent delegates to the Lower House.

Most parts of medieval Hungary were integrated in the Habsburg Monarchy in the 1690s. The monarchs confirmed the nobles' privileges several times, but their attempts to strengthen royal authority regularly brought them into conflicts with the nobility, who made up about 4,6% of the society. Reformist noblemen demanded the abolition of noble privileges from the 1790s, but their program was enacted only during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. Most noblemen lost their estates after the emancipation of their serfs, but the aristocrats preserved their distinguished social status. State administration employed thousands of impoverished noblemen in Austria-Hungary. Prominent (mainly Jewish) bankers and industrialists were awarded with nobility, but their social status remained inferior to traditional aristocrats. Noble titles were abolished only in 1947, months after Hungary was proclaimed a republic.

Origins

The Magyars (or Hungarians) dwelled in the Pontic steppes when they first appeared in the written sources in the mid-9th century.[1] Muslim merchants described them as wealthy nomadic warriors, but they also noticed that the Magyars had extensive arable lands.[2][3] Masses of Magyars crossed the Carpathian Mountains after the Pechenegs invaded their lands in 894 or 895.[4] They settled in the lowlands along the Middle Danube, annihilated Moravia and defeated the Bavarians in the 900s.[5][6] Slovak historians write, at least three Hungarian noble kindreds[note 1] were descended from Moravian aristocrats.[7] Historians who say that the Vlachs (or Romanians) were already present in the Carpathian Basin in the late 9th century propose that the Vlach knezes (or chieftains) also survived the Hungarian Conquest.[8][9] Neither of the two continuity theories is universally accepted.[10][11]

Constantine Porphyrogenitus recorded around 950 that the Hungarians were organized into tribes and each had its own "prince".[12][13] The tribal leaders most probably bore the title úr, as it is suggested by Hungarian terms – ország (now "realm") and uralkodni ("to rule") – deriving from this noun.[14] Porphyrogenitus noted that the Magyars spoke both Hungarian and "the tongue of the Chazars",[15] showing that at least their leaders were bilingual.[16]

Archaeological research revealed that most settlements comprised small pit-houses and log cabins in the 10th century, but literary sources mentioned that tents were still in use in the 12th century.[17] No archeological finds evidence fortresses in the Carpathian Basin in the 10th century, but fortresses were also rare in Western Europe during the same period.[18][19] A larger log cabin – measuring 5 m × 5 m (16 ft × 16 ft) – which was built on a foundation of stones in Borsod was tentatively identified as the local leader's abode.[18]

More than a 1,000 graves yielding sabres, arrow-heads and bones of horses show that mounted warriors formed a significant group in the 10th century.[20] The highest-ranking Hungarians were buried either in large cemeteries (where hundreds of graves of men buried without weapons surrounded their burial places), or in small cemeteries with 25–30 graves.[21] The wealthy warriors' burial sites yielded richly decorated horse harness, and sabretaches ornamented with precious metal plaques.[22] Rich women's graves contained their braid ornaments and rings made of silver or gold and decorated with precious stones.[22] The most widespread decorative motifs which can be regarded as tribal totems – the griffin, wolf and hind – were rarely applied in Hungarian heraldry in the following centuries.[23] Defeats during the Hungarian invasions of Europe and clashes with the paramount rulers from the Árpád dynasty decimated the leading families by the end of the 10th century.[24] The Gesta Hungarorum, which was written around 1200, claimed that dozens of noble kindreds flourishing in the late 12th century[note 2] had been descended from tribal leaders, but most modern scholars do not regard this list as a reliable source.[25][26]

Middle Ages

Development

Stephen I, who was crowned the first king of Hungary in 1000 or 1001, defeated the last resisting tribal chieftains.[27][28] Earthen forts were built in the entire kingdom and most of them developed into centers of royal administration.[29] About 30 administrative units, known as counties, were established before 1040; more than 40 new counties were organized during the next centuries.[30][31][32] Each county was headed by a royal official, the ispán, whose office was not hereditary.[33] The royal court provided further career opportunities.[34] Actually, as Martyn Rady noted, the "royal household was the greatest provider of largesse in the kingdom" where the royal family owned more than two-thirds of all lands.[35] The palatine – the head of the royal household – was the highest-ranking royal official.[36]

The kings appointed their officials from among the members of about 110 aristocratic kindreds.[36][37] These aristocrats were descended either from native (that is, Magyar, Kabar, Pecheneg or Slavic) chiefs, or from foreign knights who had migrated to the country in the 11th and 12th centuries.[38][39] The foreign knights had been trained in the Western European art of war, which contributed to the development of heavy cavalry.[40][41] Their descendants were labelled as newcomers for centuries,[42] but intermarriages between natives and newcomers were not rare, which enabled their integration.[43] The monarchs pursued an expansionist policy from the late 11th century.[44] Ladislaus I seized Slavonia – the plains between the river Drava and the Dinaric Alps – in the 1090s.[45][46] His successor, Coloman, was crowned king of Croatia in 1102.[47] Both realms retained their own customs and Hungarians rarely received land grants in Croatia.[47] According to customary law, Croatians could not be obliged to cross the river Drava to fight in the royal army at their own expenses.[48]

The earliest laws authorized the landowners to freely dispose of their private estates, but customary law prescribed that inherited lands could only be alienated with the consent of the owner's kinsmen who could inherit them.[49][50] From the early 12th century, only family lands traceable back to a grant made by Stephen I could be inherited by the deceased owner's distant relatives; other estates escheated to the Crown if their owner did not have offspring and brothers.[50][51] Aristocratic families held their inherited domains in common for generations before the 13th century.[40] Thereafter the division of inherited property became the standard practice.[40] Even families descending from wealthy kindreds could impoverish through the regular divisions of their estates.[52]

The basic unit of estate organization was mentioned as praedium or allodium in medieval documents.[53][54] A praedium was a piece of land (either a whole village, or only a part of it) with well-marked borders.[53][54] Most wealthy landowners' domains consisted of scattered praedia, located in several villages.[55] Due to the scarcity of documentary evidence, the size of the private estates cannot be determined.[56] The descendants of Otto Győr remained wealthy landowners even after he had donated 360 households to the newly established Zselicszentjakab Abbey in 1061.[57] The establishment of monasteries by wealthy individuals was common.[40] Such proprietary monasteries served as burial places for their founders and the founders' descendants, who were regarded the co-owners, or from the 13th century, co-patrons, of the monastery.[40] Wolf identifies the small motte forts, built on artificial mounds and protected by a ditch and a palisade, that appeared in the 12th century as the centers of private estates.[58] A part of the praedium was cultivated by unfree peasants, but other plots were hired out in return for in-kind taxes.[54]

The term "noble" was rarely used and poorly defined before the 13th century: it could refer to a courtier, a landowner with judicial powers, or even to a common warrior.[37] The existence of a diverse group of warriors, who were subjected to the monarch, royal officials or prelates is well documented.[59] The castle warriors, who were exempted of taxation, held hereditary landed property around the royal castles.[60][61] Light-armored horsemen, known as lövős (or archers), and armed castle folk, mentioned as őrs (or guards), defended the gyepűs (or borderlands).[62]

Golden Bulls

Only the court dignitaries and ispáns were mentioned as noblemen in official documents from the end of the 12th century.[37] The aristocrats had adopted most elements of chivalric culture.[63][64] They regularly named their children after Paris of Troy, Hector, Tristan, Lancelot and other heroes of Western European chivalric romances.[63] The first tournaments were held around the same time.[65]

The regular alienation of royal estates is well-documented from the 1170s.[66] The monarchs also granted immunities, exempting the grantee's estates of the jurisdiction of the ispáns, or even renouncing royal revenues that had been collected there.[66] Béla III was the first Hungarian monarch to give away a whole county to a nobleman: he granted Modrus in Croatia to Bartholomew of Krk in 1193, stipulating that Bartholomew was to equip warriors for the royal army.[67] Béla's son, Andrew II, decided to "alter the conditions" of his realm and to "distribute castles, counties, lands and other revenues" to his officials, as he narrated in a diploma in 1217.[68] Instead of granting the estates in fief, with an obligation to render future services, he gave them as allods, in reward for the grantee's previous acts.[69] The great officers who were the principal beneficiaries of his grants were mentioned as barons of the realm from the late 1210s.[70][71]

Donations to such a large scale accelerated the development of a wealthy group of landowners, most descending from high-ranking kindreds.[70][71] Some wealthy landowners[note 3] could afford to build stone castles in the 1220s.[72] Closely related aristocrats were distinguished from other lineages through a reference to their (actual or presumed) common ancestor with the words de genere ("from the kindred").[73] Families descending from the same kindred adopted similar insignia.[note 4][74] The author of the Gesta Hungarorum fabricated genealogies for them and emphasized that they could never be excluded from "the honor of the realm",[75] that is from state administration.[52]

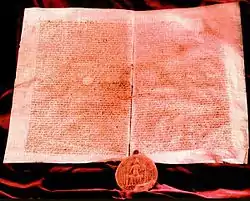

The new owners of the alienated royal estates wanted to subject the freemen, castle warriors and other privileged groups of people living in or around their domains.[76] The threatened groups wanted to achieve the confirmation of their status as royal servants, emphasizing that they were only to serve the king.[77][78] Béla III issued the first extant royal charter about the grant of this rank to a castle warrior.[79] The royal servants' privileges were enacted in Andrew II's Golden Bull of 1222.[80] They were exempt from taxation; they were to fight in the royal army without a proper compensation only if enemy forces invaded the kingdom; their cases could only be judged by the monarch or the palatine; and their arrest without a verdict was prohibited.[81][82][83] According to the Golden Bull, only royal servants who died without a son could freely will their estates, but even in this case, their daughters were entitled to the daughters' quarter (that is one-quarter of their possessions).[81][84] The final article of the Golden Bull authorized the bishops, barons and other nobles to resist the monarch if he ignored its provisions.[85] Most provisions of te Golden Bull were first confirmed in 1231.[86]

The clear definition of the royal servants' liberties distinguished them from all other privileged groups whose military obligations remained theoretically unlimited.[80] From the 1220s, the royal servants were regularly called noblemen and started to develop their own corporate institutions at the counties' level.[87] In 1232, the royal servants of Zala County asked Andrew II to authorize them "to judge and do justice", stating that the county had slipped into anarchy.[88] The king granted their request and Bartholomew, Bishop of Veszprém, sued one Ban Oguz for properties before their community.[88] The "community of the royal servants of Zala" was regarded a juridical person with its own seal.[88]

The first Mongol invasion of Hungary proved the importance of well-fortified places and heavy-armored cavalry in 1241 and 1242.[89][90] During the following decades, Béla IV of Hungary gave away large parcels of the royal demesne, expecting that the new owners would build stone castles there.[91][92] Béla's burdensome castle-building program was unpopular, but he achieved his aim: almost 70 castles were built or reconstructed during his reign.[93] More than half of the new or reconstructed castles was located in noblemen's domains.[94] Most new castles were erected on rocky peaks, mainly along the western and northern borderlands.[95] The spread of stone castles made profound changes in the structure of landholding, because castles could not be maintained without proper income.[96] Lands and villages were legally attached to each castle and castles were thereafter always alienated and inherited along with these "appurtenances".[97]

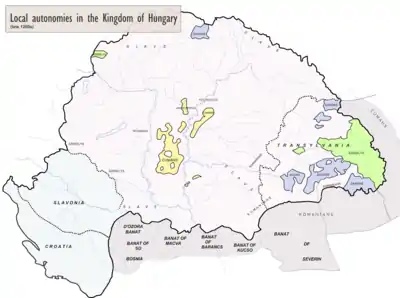

The royal servants were legally identified as nobles in 1267.[98] In this year, "the nobles of all Hungary, called royal servants" persuaded Béla IV and his son, Stephen, to hold an assembly and confirm their collective privileges.[98] Other groups of land-holding warriors could also be called nobles, but they were always distinguished from the true noblemen.[99][100] The Vlach noble knezes who had landed property in the Banate of Severin were obliged to fight in the army of the ban (or royal governor).[101] Most warriors known as the noble sons of servants were descended from freemen or liberated serfs who received estates from Béla IV in Upper Hungary on the condition that they were to jointly equip a fixed number of knights.[99][102] The nobles of the Church formed the armed retinue of the wealthiest prelates.[100][103] The nobles of Turopolje in Slavonia were required to provide food and fooder to high-ranking royal officials.[104] The Székelys and Saxons firmly protected their communal liberties which prevented their leaders from exercise noble privileges in the Székely and Saxon territories in Transylvania.[105] Székelys and Saxons could only enjoy the liberties of noblemen if they held estates outside the lands of the two privileged communities.[105]

Most noble families failed to adopt a strategy to avoid the division of their inherited estates into dwarf-holdings through generations.[106] Daughters could only demand the cash equivalent of the quarter of their father's estates,[107] but younger sons rarely remained unmarried.[106] Impoverished noblemen had little chance to receive land grants from the kings, because they were unable to participate in the monarchs' military campaigns,[108] but commoners who bravely fought in the royal army were regularly ennobled.[109]

Self-government and oligarchs

Historian Erik Fügedi noted that "castle bred castle" in the second half of the 13th century: if a landowner erected a fortress, his neighbors were also to build one to defend their own estates.[110] Between 1271 and 1320, at least 155 new fortresses were built by noblemen or prelates, and only about a dozen castles were erected on royal domains.[111] Most castles consisted of a tower, surrounded by a fortified courtyard, but the tower could also be built into the walls.[112] Noblemen who could not erect fortresses were occasionally forced to abandon their inherited estates or seek the protection of more powerful lords, even through renouncing their liberties.[note 5][113]

The lords of the castles had to hire a professional staff for the defence of the castle and the management of its appurtenances.[114] They primarily employed nobles who held nearby estates, which gave rise to the development of a new institution, known as familiaritas.[115][116] A familiaris was a nobleman who entered into the service of a wealthier landowner in exchange for a fixed salary or a portion of revenue, or rarely for the ownership or usufruct of a piece of land.[116] Unlike a conditional noble, a familiaris remained in theory an independent landholder, only subjected to the monarch.[117][118]

The monarchs took an oath at their coronation, which included a promise to respect the noblemen's liberties from the 1270s.[119] The counties gradually transformed into an institution of the noblemen's local autonomy.[120] Noblemen regularly discussed local matters at the general assemblies of the counties.[121][122] The sedria (or law courts of the counties) became important elements of the administration of justice.[88] They were headed by the ispáns or their deputies, but they consisted of four (in Slavonia and Transylvania, two) elected local noblemen, known as judges of the nobles.[88][98]

Hungary fell into a state of anarchy because of the minority of Ladislaus IV in the early 1270s.[123] To restore public order, the prelates convoked the barons and the delegates of the noblemen and Cumans to a general assembly near Pest in 1277.[123] This first Diet (or parliament) declared the monarch to be of age.[123] In the early 1280s, Simon of Kéza associated the Hungarian nation with the nobility in his Deeds of the Hungarians, emphasizing that the community of noblemen held real authority.[119][124]

The barons took advantage of the weakening of royal authority and seized large contiguous territories.[125] The monarchs could not appoint and dismiss their officials at will any more.[125] The most powerful barons – known as oligarchs in modern historiography – appropriated royal prerogatives, combining private lordship with their administrative powers.[126] When Andrew III, the last male member of the Árpád dynasty, died in 1301, about a dozen lords[note 6] held sway over most parts of the kingdom.[127]

Age of the Angevins

Ladislaus IV's great-nephew, Charles I, who was a scion of the Capetian House of Anjou, restored royal power in the 1310s and 1320s.[128] He captured the oligarchs' castles, which again secured the preponderance of the royal demesne.[129] He refuted to confirm the Golden Bull in 1318 and claimed that noblemen had to fight in his army at their own expenses.[130] He ignored customary law and regularly "promoted a daughter to a son", granting her the right to inherit her father's estates.[131][132][133] He reorganized the royal household, appointing pages and knights to form his permanent retinue.[134] He established the Order of Saint George, which was the first chivalric order in Europe.[129][65] He was the first Hungarian monarch to grant coats of arms (or rather crests) to his subjects.[135] Charles based royal administration on honors (or office fiefs), distributing most counties and royal castles among his highest-ranking officials.[128][129][136] These "baronies", as Matteo Villani recorded it around 1350, were "neither hereditary nor lifelong", but Charles rarely dismissed his most trusted barons.[137][138] Each baron was required to hold his own banderium (or armed retinue), distinguished by his own banner.[139]

In 1351, Charles's son and successor, Louis I confirmed all provisions of the Golden Bull, save the one that authorized childless noblemen to freely will their estates.[140][141] Instead, he introduced an entail system, prescribing that childless noblemen's landed property "should descend to their brothers, cousins and kinsmen".[142] The concept of aviticitas also protected the Crown's interests: only kins within the third degree could inherit a nobleman's property and noblemen who had only more distant relatives could not dispose of their property without the king's consent.[143] Louis I emphasized that all noblemen enjoyed "one and the selfsame liberty" in his realms[140] and secured all privileges that nobles owned in Hungary proper to their Slavonian and Transylvanian peers.[144] He rewarded dozens of Vlach knezes and voivodes with true nobility for military merits.[145] The vast majority of the noble sons of servants achieved the status of true noblemen without a formal royal act, because the memory of their conditional landholding fell into oblivion.[146] Most of them preferred Slavic names even in the 14th century, showing that they spoke the local Slavic vernacular.[147] Other groups of conditional nobles remained distinguished from true noblemen.[148] They developed their own institutions of self-government, known as seats or districts.[149] Louis decreed that only Catholic noblemen and knezes could hold landed property in the district of Karánsebes (now Caransebeș in Romania) in 1366, but Orthodox landowners were not forced to convert to Catholicism in other territories of the kingdom.[150] Even the Catholic bishop of Várad (now Oradea in Romania) authorized his Vlach voivodes to employ Orthodox priests.[151] The king granted the district of Fogaras (around present-day Făgăraș in Romania) to Vladislav I of Wallachia in fief in 1366.[152] In his new duchy, Vladislaus I donated estates to Wallachian boyars; their legal status was similar to the position of the knezes in other regions of Hungary.[153]

Royal charters customarily identified noblemen and landowners from the second half of the 14th century.[154] A man who lived in his own house on his own estates was described as living "in the way of nobles", in contrast with those who did not own landed property and lived "in the way of peasants".[144] A verdict of 1346 declared that a noble woman who was given in marriage to a commoner should receive her inheritance "in the form of an estate in order to preserve the nobility of the descendants born of the ignoble marriage".[155] Her husband was also regarded noblemen – a noble by his wife – according to the local customs of certain counties.[156]

The peasants' legal position had been standardized in almost the entire kingdom by the 1350s.[157][141] The iobagiones (or free peasant tenants) were to pay seigneurial taxes, but were rarely obliged to perform labour service.[141] In 1351, the king ordered that the ninth – a tax payable to the landowners – was to be collected from all iobagiones, thus preventing landowners from offering lower taxes to persuade tenants to move from other lords' lands to their estates.[142] In 1328, all landowners were authorized to administer justice on their estates "in all cases except cases of theft, robbery, assault or arson".[158] The kings started to grant noblemen the right to execute or mutilate criminals who were captured in their estates.[159] The most influential noblemen's estates were also exempted of the jurisdiction of the sedria.[160]

Emerging Estates

Royal power quickly declined after Louis I died in 1382.[161] His son-in-law, Sigismund of Luxembourg, entered into a formal league with the aristocrats who had elected him king in early 1387.[162] He had to give away more than the half of the 150 royal castles to his supporters before he could strengthen his authority in the early 15th century.[163] His most favorites were foreigners,[note 7] but old Hungarian families[note 8] also took advantage of his magnanimity.[164] The wealthiest noblemen, known as magnates, built comfortable castles in the countryside which became important centers of social life.[165] These fortified manor houses always contained a hall for representative purposes and a private chapel.[166] Sigismund regularly invited the magnates to the royal council even if they did not hold higher offices.[167] He founded a new chivalric order, the Order of the Dragon, in 1408 to award his most loyal supporters.[168]

The expansion of the Ottoman Empire reached the southern frontiers in the 1390s.[169] A large anti-Ottoman crusade ended with a catastrophic defeat near Nicopolis in 1396.[170] Next year, Sigismund held a Diet in Temesvár (now Timișoara in Romania) to strengthen the defence system.[170][171] He confirmed the Golden Bull, but without the two provisions that limited the noblemen's military obligations and established their right to resist the monarchs.[170] The Diet obliged all landowners to equip one archer for 20 peasant plots on their domains to serve in the royal army.[172][173] Sigismund granted large estates to neighboring Orthodox rulers in Hungary[note 9] to secure their alliance.[174] They established Basilite monasteries on their estates.[175]

Sigismund's son-in-law, Albert of Habsburg, was elected king in early 1438, but only after he promised to always make important decisions with the consent of the royal council.[176][177] After he died in 1439, a civil war broke out between the partisans of his son, Ladislaus the Posthumous, and the supporters of Vladislaus III of Poland.[178] Ladislaus the Posthumous was crowned with the Holy Crown of Hungary, but the Diet proclaimed the coronation invalid.[179] Vladislaus died fighting against the Ottomans during the Crusade of Varna in 1444 and the Diet elected seven captains in chief to administer the kingdom.[180] The talented military commander, John Hunyadi, was elected the sole regent in 1446.[180]

The Diet developed from a consultative body into an important institution of law making in the 1440s.[180] The magnates were always invited to attend it in person.[179] Lesser noblemen were also entitled to personally attend the Diet, but they were in most cases represented by delegates.[181] The noble delegates were almost always the familiares of the magnates.[181]

Birth of titled nobility and the Tripartitum

Hunyadi was the first noble to receive a hereditary title from a Hungarian monarch.[182] Ladislaus the Posthumous granted him the Saxon district of Bistritz (now Bistrița in Romania) with the title perpetual count in 1453.[182][183] Hunyadi's son, Matthias Corvinus, who was elected king in 1458, rewarded further noblemen with the same title.[184] Fügedi states, 16 December 1487 was the "birthday of the estate of magnates in Hungary",[185] because an armistice signed on this day listed 23 Hungarian "natural barons", contrasting them with the high officers of state, who were mentioned as "barons of office".[167][185] Corvinus' successor, Vladislaus II, and Vladislaus' son, Louis II, started to formally reward important persons of their government with the hereditary title of baron.[186]

Differences of the nobles' wealth increased in the second half of the 15th century.[187] About 30 families owned more than a quarter of the territory of the kingdom when Corvinus died in 1490.[187] Average magnates held about 50 villages, but the regular division of inherited landed property could cause the impoverishment of aristocratic families.[note 10][188] Strategies applied to avoid this – family planning and celibacy – led to the extinction of most aristocratic families after a few generations.[note 11][189] The tenth of all lands in the kingdom was in the possession of about 55 wealthy noble families.[187] Other nobles held almost one third of the lands, but this group included 12–13,000 peasant-nobles who owned a single plot (or a part of it) and had no tenants.[190] The Diets regularly compelled the peasant-nobles to pay tax on their plots.[190]

The Diet ordered the compilation of customary law in 1498.[191] István Werbőczy completed the task, presenting a law-book at the Diet in 1514.[191][192] His Tripartitum – The Custormary Law of the Renowned Kingdom of Hungary in Three Parts – was never enacted, but it was consulted at the law courts for centuries.[193][194] It summarized the noblemen's fundamental privileges in four points:[195] noblemen were only subject to the monarch's authority and could only be arrested in a due legal process, furthermore, they were exempted of all taxes and were entitled to resist the king if he attempted to interfere with their privileges.[196] Werbőczy also implied that Hungary was actually a republic of nobles headed by a monarch, stating that all noblemen "are members of the Holy Crown"[197] of Hungary.[195] Quite anachronistically, he emphasized the idea of all noblemen's legal equality, but he had to admit that the high officers of the realm, whom he mentioned as "true barons", were legally distinguished from other nobles.[198] He also mentioned the existence of a distinct group, who were barons "in name only", but without specifying their peculiar status.[140]

The Tripartitum regarded the kindred as the basic unit of nobility.[199] A noble father exercised almost autocratic authority over his sons, because he could imprison them or offer them as a hostage for himself.[200] His authority ended only if he divided his estates with his sons, but the division could rarely be enforced.[200] The "betrayal of fraternal blood" (that is, a kinsman's "deceitful, sly, and fraudulent ... disinheritance")[201] was a serious crime, which was punished by loss of honor and the confiscation of all property.[202] Although the Tripartitum did not explicitly mention it, a nobleman's wife was also subject to his authority.[203] She received her dower from her husband at the consumpiton of their marriage.[203] If her husband's died, she inherited his best coach-horses and clothes.[204]

Demand for foodstuffs rapidly grew in Western Europe in the 1490s.[205] The landowners wanted to take advantage of the growing prices.[206] They demanded labour service from their peasant tenants and started to collect the seigneurial taxes in kind.[207] The Diets passed decrees that restricted the peasants' right to free movement and increased their burdens.[205] The peasants' grievances unexpectedly culminated in a rebellion in May 1514.[205][208] The rebels captured manor houses and murdered dozens of noblemen, especially in the Great Hungarian Plain.[209] The voivode of Transylvania, John Zápolya, annihilated their main army at Temesvár on 15 July.[210] György Dózsa and other leaders of the peasant war were tortured and executed, but most rebels received a pardon.[210] The Diet punished the peasantry as a group, condemning them to perpetual servitude and depriving them of the right of free movement.[210][211] The Diet also enacted the serfs' obligation to provide one day's labour service for their lords each week.[211]

Early modern and modern times

Tripartite Hungary

.jpg.webp)

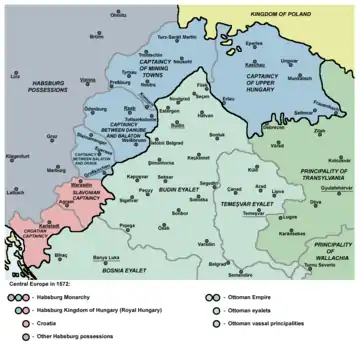

The Ottomans annihilated the royal army in the Battle of Mohács.[212] Louis II died fleeing from the battlefield and two claimants, John Zápolya and Ferdinand of Habsburg, were elected kings.[213] Ferdinand tried to reunite Hungary after Zápolya died in 1540, but the Ottoman Sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent intervened and captured Buda in 1541.[214] The sultan allowed Zápolya's widow, Isabella Jagiellon, to rule the lands east of the river Tisza on behalf of her infant son, John Sigismund, in return for a yearly tribute.[215] His decision divided Hungary into three parts: the central territories were occupied by the Ottomans; John Sigismund's eastern Hungarian Kingdom developed into the autonomous Principality of Transylvania; and the Habsburg monarchs preserved the northern and western territories (or Royal Hungary).[216]

Most noblemen fled from the central regions to the unoccupied territories.[217] Peasants who lived along the borders paid taxes both to the Ottomans and to their former lords.[218] Commoners were regularly recruited to serve in the royal army or the magnates' retinues to replace the noblemen who had perished during the fights.[219] The irregular hajdú foot-soldiers – mainly runaway serfs and dispossessed noblemen – became important elements of the defence forces.[219][220] Stephen Bocskai, Prince of Transylvania, settled 10,000 hajdús in 7 villages and exempted them of taxation in 1605, which was the "largest collective ennoblement" in the history of Hungary.[221][222]

The noblemen formed one of the three nations (or Estates of the realm) in Transylvania, but they could rarely challenge the princes' authority.[223] In Royal Hungary, the magnates successfully protected the noble privileges, because their vast domains were almost fully exempted of the royal officials' authority.[224] Their manors were fortified in the "Hungarian manner" (with walls made of earth and timber) in the 1540s.[225] The Hungarian noblemen could also count on the support of the Transylvanian princes against the Habsburg monarchs.[224] Intermarriages among Austrian, Czech and Hungarian aristocrats[note 12] gave rise to the development of a "supranational aristocracy" in the Habsburg Monarchy.[226] Foreign aristocrats regularly received Hungarian citizenship, and Hungarian noblemen were often naturalized in the Habsburgs' other realms.[note 13][227] The Habsburg kings rewarded the most powerful magnates with hereditary titles from the 1530s.[186]

The aristocrats supported the spread of Reformation.[228] Most noblemen adhered to Lutheranism in the western regions of Royal Hungary, but Calvinism was the dominant religion in other regions and in Transylvania.[229] John Sigismund even promoted anti-Trinitarian views,[230] but most Unitarian noblemen perished in battles in the early 1600s.[231] The Habsburgs remained staunch supporters of Counter-Reformation and the most prominent aristocratic families[note 14] converted to Catholicism in Royal Hungary in the 1630s.[232][233] The Calvinist princes of Transylvania supported their co-religionists.[232] Gabriel Bethlen granted nobility to all Calvinist pastors.[234]

Both the kings and the Transylvanian princes regularly ennobled commoners without granting landed property to them.[235] Jurisprudence, however, maintained that only those who owned land which was cultivated by serfs could be regarded fully-fledged noblemen.[236] Armalists – noblemen who hold a charter of ennoblement, but not a single plot of land – and peasant-nobles continued to pay taxes, for which they were collectively known as taxed nobility.[236] Nobility could be purchased from the kings who were always in need of funds.[237] Landowners also benefitted from the enoblement of their serfs, because they could demand a fee for their consent.[237]

The Diet was officially divided into two chambers in Royal Hungary in 1608.[238][239] All adult male members of the titled noble families had a seat at the Upper House.[239] The lesser noblemen elected 2 or 3 delegates at the general assemblies of the counties to represent them in the Lower House.[238] The Croatian and Slavonian magnates also had a seat at the Upper House and the sabor (or Diet) of Croatia and Slavonia sent delegates to the Lower House.[238]

Liberation and war of independence

pg064_Zr%C3%ADnyi_Ilona.jpg.webp)

Relief forces from the Holy Roman Empire and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth inflicted a crushing defeat on the Ottomans at Vienna in 1683.[240] The Ottomans were expelled from Buda in 1686.[241] Michael I Apafi, the prince of Transylvania, acknowledged the suzerainty of Emperor Leopold I (who was also king of Hungary) in 1687.[241] Grateful for the liberation of Buda, the Diet abolished the noblemen's right to resist the monarch for the defense of their liberties.[242] Leopold confirmed the privileges of the Transylvanian Estates in 1690.[243][244]

In 1688, the Diet authorized the aristocrats to establish a special trust, known as fideicommissum, with royal consent to prevent the distribution of their landed wealth among their descendants.[245] In accordance with the traditional concept of aviticitas, inherited estates could not be subject to the trust.[245] Estates in fideicommissum were administered by one member of the family, but he was responsible for the proper boarding of his relatives.[245]

The Ottomans acknowledged the loss of central Hungary in 1699.[242] Leopold set up a special committee to distribute the lands in the reconquered territories.[246] The descendants of the noblemen who had held estates there before the Ottoman conquest were required to provide documentary evidence to substantiate their claims to the ancestral lands.[246] Even if they could present documents, they were to pay a fee – a tenth of the value of the claimed property – as a compensation for the costs of the liberation war.[247][246] Few noblemen could meet the criteria and more than the half of the recovered lands was distributed among foreigners.[248] They were naturalized, but most of them never visited Hungary.[249]

The Habsburg administration doubled the amount of the taxes to be collected in Hungary and demanded almost one third of the taxes (1,25 million florins) from the clergy and the nobility.[250] The palatine, Prince Paul Esterházy, convinced the monarch to reduce the noblemen's tax-burden to 0,25 million florins, but the difference was to be paid by the peasantry.[250] Leopold did not trust the Hungarians, because a group of magnates had conspired against him in the 1670s.[242] Mercenaries replaced the Hungarian garrisons and they frequently plundered the countryside.[242][250] The monarch also supported Cardinal Leopold Karl von Kollonitsch's attempts to restrict the Protestants' rights.[247] Tens of thousands of Catholic Germans and Orthodox Serbs were settled in the reconquered territories.[247]

The outbreak of the War of the Spanish Succession gave opportunity for the discontented Hungarians to rise up against Leopold.[250] They regarded one of the wealthiest aristocrats, Prince Francis II Rákóczi, their leader.[250] Rákóczi's War of Independence lasted from 1703 to 1711.[242] Although the rebels were forced to yield, the Treaty of Szatmár granted a general amnesty for them and the new Habsburg monarch, Charles III, promised to respect the privileges of the Estates of the realm.[251]

Cooperation, absolutism and reforms

Charles III again confirmed the privileges of the Estates of the "Kingdom of Hungary, and the Parts, Kingdoms and Provinces thereto annexed" in 1723 in return for the enactment of the Pragmatic Sanction which established his daughters' right to succeed him.[252][253] Montesquieu who visited Hungary in 1728 regarded the relationship between the king and the Diet as a good example of the separation of powers.[254] The magnates almost monopolized the highest offices, but both the Hungarian Court Chancellery – the supreme body of royal administration – and the Lieutenancy Council – the most important administrative office – also employed lesser noblemen.[255] Protestants were in practice excluded from public offices after a royal decree, the Carolina Resolutio, obliged all candidates to take an oath on the Virgin Mary.[256]

The Peace of Szatmár and the Pragmatic Sanction maintained that the Hungarian nation consisted of the privileged groups, independently of their ethnicity,[257] but the first debates along ethnic lines appeared in the early 18th century.[258] The jurist Mihály Bencsik claimed that the burghers of Trencsén (now Trenčín in Slovakia) should not send delegates to the Diet, because their ancestors had been forced to yield to the conquering Magyars in the 890s.[259] A priest, Ján B. Magin, wrote a response, arguing that ethnic Slovaks and Hungarians enjoyed the same rights.[260] In Transylvania, a bishop of the Romanian Greek Catholic Church, Baron Inocențiu Micu-Klein, demanded the recognition of the Romanians as the fourth Nation.[261]

Maria Theresa succeeded Charles III in 1740, which gave rise to the War of the Austrian Succession.[262] The noble delegates offered their "lives and blood" for their new "king" and the declaration of the general levy of the nobility was crucial at the beginning of the war.[252] Grateful for their support, Maria Therese strengthened the links between the Hungarian nobility and the monarch.[263][264] She established the Theresian Academy and the Royal Hungarian Bodyguard for young Hungarian noblemen.[265] Both institutions enabled the spread of the ideas of the Age of Enlightenment.[note 15][266][267] Freemasonry became also popular, especially among the magnates.[268]

Cultural differences between the magnates and lesser noblemen increased.[269] The magnates adopted the lifestyle of the imperial aristocracy, moving between their summer palaces in Vienna and their newly built splendid residences in Hungary.[269] Prince Miklós Esterházy employed Joseph Haydn; Count János Fekete, a fierce protector of noble privileges, bombarded Voltaire with letters and dilettante poems;[270] Count Miklós Pálffy proposed to tax the nobles to finance a standing army.[271] However, most noblemen was unwilling to renounces their privileges.[272] Lesser noblemen also insisted on their traditional way of life and lived in simple houses, made of timber or packed clay.[273]

Maria Therese did not hold Diets after 1764.[271] She regulated the relationship of landowners and their serfs in a royal decree in 1767.[274] Her son and successor, Joseph II, known as the "king in hat", was never crowned, because he wanted to avoid the coronation oath.[275] He introduced reforms which clearly contradicted local customs.[276] He replaced the counties with districts and appointed royal officials to administer them.[277] He also abolished serfdom, securing all peasants' right to free movement after the revolt of Romanian peasants in Transylvania.[277] He ordered the first census in Hungary in 1784.[278] According to its records, the nobility made up about 4,5% of the male population in the Lands of the Hungarian Crown (with 155,519 noblemen in Hungary proper, and with 42,098 noblemen in Transylvania, Croatia and Slavonia).[279][280] The nobles' proportion was significantly higher (6–16%) in the northeastern and eastern counties, and lesser (3%) in Croatia and Slavonia.[279] Poor noblemen, who were mocked as "nobles of the seven plum trees" or "sandal-wearing nobles", made up almost 90% of the nobility.[281] Previous investigations of nobility show that more than half of the noble families received this rank after 1550.[237]

The few reformist noblemen greeted the news of the French Revolution with enthusiasm.[282] József Hajnóczy translated the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen into Latin and János Laczkovics published its Hungarian translation.[282] To appease the Hungarian nobility, Joseph II revoked almost all his reforms on his deathbed in 1790.[283] His successor, Leopold II, convoked the Diet and confirmed the liberties of the Estates of the realm, emphasizing that Hungary was a "free and independent" realm, governed by its own laws.[277][284] News about the Jacobin terror in France strengthened royal power.[285] Hajnóczy and other radical (or "Jacobin") noblemen who had discussed the possibility of the abolishment of all privileges in secret societies were captured and executed or imprisoned in 1795.[286] The Diets voted the taxes and the recruits that Leopold's successor, Francis, demanded between 1792 and 1811.[287]

The last general levy of the nobility was declared in 1809, but Napoleon easily defeated the noble troops near Győr.[287] Agricultural bloom encouraged the landowners to borrow money and to buy new estates or to establish mills during the war, but most of them became bankrupt after peace was restored in 1814.[288] The concept of aviticitas prevented both the creditors from collecting their money and the debtors from selling their estates.[289] Radical nobles played a crucial role in the reform movements of the early 19th century.[290] Gergely Berzeviczy attributed the backwardness of the local economy to the peasants' serfdom already around 1800.[291] Ferenc Kazinczy and János Batsányi initiated a language reform, fearing of the disappearance of the Hungarian language.[290] The poet Sándor Petőfi, who was a commoner, ridiculed the conservative noblemen in his poem The Magyar Noble, contrasting their anachronistic pride and their idle way of life.[292]

From the 1820s, a new generation of reformist noblemen dominated the political life.[293] Count István Széchenyi demanded the abolition of the serfs' labour service and the entail system, stating that "We, well-to-do landowners are the main obstacles to the progress and greater development of our fatherland".[294] He established clubs in Pressburg and Pest and promoted horse racing, because he wanted to encourage the regular meetings of magnates, lesser noblemen and burghers.[295] Széchenyi's friend, Baron Miklós Wesselényi, demanded the creation of a constitutional monarchy and the protection of civil rights.[296] A lesser nobleman, Lajos Kossuth, became the leader of the most radical politicians in the 1840s.[295] He emphasized that the Diets and the counties were the privileged groups' institutions and only a wider social movement could secure the development of Hungary.[297]

The official use of the Hungarian language spread from the late 18th century,[298] although ethnic Hungarians made up only about 38% of the population.[299] Kossuth declared that all who wanted to enjoy the liberties of the nation should learn Hungarian.[300] Count Janko Drašković recommended that Croatian should replace Latin as the official language in Croatia and Slavonia.[301] The Slovak Ľudovít Štúr stated that the Hungarian nation consisted of many nationalities and their loyalty could be strengthened by the official use of their languages.[302]

Revolution and neo-absolutism

News of the uprisings in Paris and Vienna reached Pest on 15 March 1848.[303] Young intellectuals proclaimed a radical program, known as the Twelve Points, demanding equal civil rights to all citizens.[304] Count Lajos Batthyány was appointed the first prime minister of Hungary.[305] The Diet quickly enacted the majority of the Twelve Points and Ferdinand V sanctioned them in April.[303]

The April Laws abolished the nobles' tax-exemption and the aviticitas,[306] but the 31 fideicommissa remained intact.[307] The peasant tenants received the ownership of their plots, but a compensation was promised to the landowners.[306][308] Adult men who owned more than 0,032 km2 (7,900 acres) arable lands or urban estates with a value of at least 300 florins – about one quarter of the adult male population – were granted the right to vote at the parliamentary elections.[306] However, the noblemen's exclusive franchise in county elections was confirmed, because otherwise ethnic minorities could have easily dominated the general assemblies in many counties.[306] Noblemen made up about one quarter of the members of the new parliament, which assembled after the general elections on 5 July.[309]

The Slovak delegates demanded autonomy for all ethnic minorities at their assembly in May.[310][311] Similar demands were adopted at the Romanian delegates' meeting.[312][313] Ferdinand V's advisors persuaded the ban (or governor) of Croatia, Baron Josip Jelačić, to invade Hungary proper in September.[314][315] A new war of independence broke out and the Hungarian parliament dethroned the Habsburg dynasty on 14 April 1849.[316] Nicholas I of Russia intervened on the legitimist side and the Russian troops overpowered the Hungarian army, forcing it to surrender on 13 August.[316][317]

Hungary, Croatia (and Slavonia) and Transylvania were incorporated as separate realms in the Austrian Empire.[318] The advisors of the young emperor, Franz Joseph, declared that Hungary had lost its historic rights and the conservative aristocrats[note 16] could not persuade him to restore the old constitution.[319] Noblemen who had remained loyal to the Habsburgs were appointed to high offices,[note 17] but most new officials came from other provinces of the empire.[320][321]

The vast majority of noblemen opted for a passive resistance: they did not hold offices in state administration and tacitly obstructed the implementation of imperial decrees.[322][323] An untitled nobleman from Zala County, Ferenc Deák, became their leader around 1854.[319][323] They tried to preserve an air of superiority, but their vast majority was assimilated to the local peasantry or petty bourgeoisie during the following decades.[324] In contrast with them, the magnates, who retained about one quarter of all lands, could easily raise funds from the developing banking sector to modernize their estates.[324]

Austria-Hungary

Deák and his followers knew that the great powers did not support the disintegration of the Austrian Empire.[325] Austria's defeat in the Austro-Prussian War accelerated the rapprochement between the king and the Deák Party, which led to the Austro-Hungarian Compromise in 1867.[326] Hungary proper and Transylvania was united[327] and the autonomy of Hungary was restored within the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary.[328] Next year, the Croatian–Hungarian Settlement restored the union of Hungary proper and Croatia, but secured the competence of the sabor in internal affairs, education and justice.[329]

The Compromise strengthened the position of the traditional political elite.[330] Only about 6% of the population could vote at the general elections.[330] More than half of the prime ministers and one-third of the ministers was appointed from among the magnates from 1867 to 1918.[331] Landowners made up the majority of the members of parliament.[330] Half of the seats in municipal assemblies was preserved for the greatest taxpayers.[332] Noblemen also dominated state administration, because tens of thousands of impoverished nobles took a job at the ministries, or at the state-owned railways and post offices.[333][334] They were ardent supporters of Magyarization, denying to use the minority languages.[335]

Only nobleman who owned an estate of at least 1.15 km2 (280 acres) were regarded prosperous, but the number of estates reaching that size quickly decreased.[note 18][334] The magnates took advantage of the lesser noblemen's bankruptcies and bought new estates during the same period.[336] New fideicommissa were created which enabled the magnates to preserve the entailment of their landed wealth.[336] Aristocrats were regularly appointed to the board of directors of banks and companies.[note 19][337]

Jews were the prime movers of the development of the financing sector and industry.[338] Jewish businessmen owned more than half of the companies and more than four-fifths of the banks in 1910.[338] They also bought landed property and had acquired almost one-fifth of the estates of between 1.15–5.75 km2 (280–1,420 acres) by 1913.[338] The most prominent Jewish burghers were awarded with nobility[note 20] and there were 26 aristocratic families and 320 noble families of Jewish origin in 1918.[339][340] Many of them converted to Christianity, but other nobles did not regard them as their peers.[292]

Revolutions and counter-revolution

The First World War brought about the disintegration of Austria-Hungary in 1918.[341] The Aster Revolution – a movement of left-liberal, social democrat and radical people – persuaded King Charles IV, to appoint the leader of the opposition, Count Mihály Károlyi, prime minister on 31 October.[342][343] After the Lower House dissolved itself, Hungary was proclaimed a republic on 16 November.[344] The Hungarian National Council adopted a land reform, determining the maximum size of the estates at 1.15 square kilometres (280 acres) and ordering the distribution of the exceeding part among the local peasantry.[345] Károlyi, whose inherited domains had been mortgaged to banks, was the first to implement the reform.[345]

The Allied Powers authorized Romania to occupy new territories and ordered the withdrawal of Hungarian troops almost as far as the Tisza on 26 February 1919.[346][347] Károlyi resigned and the Bolshevik Béla Kun announced the establishment of the Hungarian Soviet Republic on 21 March.[348] All estates of over 0.43 km2 (110 acres) and all private companies employing more than 20 workers were nationalized.[349] The Bolsheviks could not stop the Romanian invasion and their leaders fled from Hungary on 1 August.[350] After Gyula Peidl's temporary government, the industrialist István Friedrich formed a coalition government with the support of the Allied Powers on 6 August.[351] The Bolsheviks' nationalization program was abolished.[351]

The social democrats boycotted the general elections in early 1920.[351] The new one-chamber parliament restored the monarchy, but without restoring the Habsburgs.[351] Instead, a Calvinist nobleman, Miklós Horthy, was elected regent on 1 March 1920.[352][353] Hungary had to acknowledge the loss of more than two thirds of its territory and more than 60% of its population (including one third of the ethnic Hungarians) in the Treaty of Trianon on 4 June.[351]

Horthy, who was not a crowned king, could not grant nobility, but he established a new order of merit, the Order of Gallantry.[354] Its members received the hereditary title of Vitéz ("brave").[354] They were also granted parcels of land, which renewed the "medieval link between land tenure and service to the crown".[354] Two Transylvanian aristocrats, Counts Pál Teleki and István Bethlen, were the most influential politicians in the interwar period.[355] The events of 1918–19 convinced them that only a "conservative democracy", dominated by the landed nobility, could secure stability.[356] Most ministers and the majority of the members of the parliament were nobles.[357] A conservative agrarian reform – limited to 8,5% of all arable lands – was introduced, but almost one third of the lands remained in the possession of about 400 magnate families.[358] The two-chamber parliament was restored in 1926, with an Upper House dominated by the aristocrats, prelates and high-ranking officials.[359][360]

Antisemitism was a leading ideology in the 1920s and 1930s.[361] A numerus clausus law limited the admission of Jewish students in the universities.[362][363] Count Fidél Pálffy was one of the leading figures of the national socialist movements, but most aristocrats disdained the radicalism of "petty officers and housekeepers".[364] Hungary participated in the German invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941 and joined to the war against the Soviet Union after the bombing of Kassa in late June.[365] Fearing of the defection of Hungary from the war, the Germans occupied the country on 19 March 1944.[366] Hundreds of thousands of Jews and tens of thousands of Romani were transferred to Nazi concentration camps with the local authorities' assistance.[367][368] The wealthiest business magnates[note 21] were to renounce their companies and banks to redeem their and their relatives' lives.[367]

Abolition

The Soviet Red Army reached the Hungarian borders and took possession of the Great Hungarian Plain by 6 December 1944.[369] Delegates from the towns and villages in the region established the Provisional National Assembly in Debrecen, which elected a new government on 22 December.[369][370] Three prominent Anti-Nazi aristocrats[note 22] had a seat in the assembly.[371] The Provisional National Government soon promised a land reform, along with the abolishment of all "anti-democratic" laws.[372] The last German troops left Hungary on 4 April 1945.[373]

The land reform was announced by Imre Nagy, the Communist Minister of Agriculture, on 17 March 1945.[374] All domains of more than 5.75 km2 (1,420 acres) were confiscated and the owners of smaller estates could retain maximum 0.58–1.73 km2 (140–430 acres) of land.[374][375] The land reform, as Bryan Cartledge noted, destroyed the nobility and eliminated the "elements of feudalism, which had persisted for longer in Hungary than anywhere else in Europe".[374] Similar land reforms were also introduced in Romania and Czechoslovakia.[376] In the two countries, ethnic Hungarian aristocrats were sentenced to death or prison as alleged war criminals.[note 23][376] Hungarian aristocrats[note 24] could retain their estates only in Burgenland (in Austria) after 1945.[377]

The Soviet military authorities controlled the general elections and the formation of a coalition government in late 1945.[378] The new parliament declared Hungary a republic on 1 February 1946.[379] An opinion poll showed that more than 75% of men and 66% of women were opposed to the use of noble titles in 1946.[380] The parliament adopted an act that abolished all noble ranks and related styles, also putting a ban on their use.[381] The new act came into force on 14 February 1947.[382]

Unofficial nobility

Statute IV of 1947 survived the political change after the fall of the single-party system and the ongoing deregulation processes during and after the 1990s (see for example Statute LXXXII of 2007,[383]) and it is still in force today. Multiple attempts have been made to have the Statute revoked, none of them succeeded.

In 2009 the Constitutional Court rejected a motion requesting the revocation of 3. § (1) – (4), the ban of using certain titles. Commenting on the rejection, the Constitutional Court felt it

... necessary to add that the Statute serves the abolition of discrimination of people on the basis of descent, which is, as the ministerial rationale of the bill conveys, "can not be compatible with the democratic public and social arrangement standing on the basis of equality. Thus, the Statute is supported by such a definite system of values that is consonant with, moreover, is an integral part of the values derived from paragraph 70/A. § (1) of the Constitution in force, prohibiting discrimination.

On September 27, 2010 (nearing the finish of the campaign for the municipal elections) István Tarlós (at the time running for the seat of Mayor in Budapest, nominated by the governing party Fidesz) and Zsolt Semjén (Deputy Prime Minister of Hungary, Christian Democratic People's Party, also member of the government), among many other politicians, have been initiated into the Vitéz Order,[384] an act the Statute explicitly prohibits.

In December 2010 two members of the opposition party JOBBIK presented a motion to revoke parts of the Statute.[385] This motion has later been revoked.[386]

In March 2011, during the drafting process of a new constitution, the possibility of revoking all legislation between 1944 and 1990 was raised.[387]

Notes

- They refer to the Hont-Pázmány, Miskolc and Bogát-Radvány clans.

- The Bár-Kalán, Csák, Kán, Lád and Szemere kindreds regarded themselves as descendant of one the legendary 7 leaders of the Hungarian Conquest.

- Andronicus Aba built a castle at Füzér, and the castle at Kabold (now Kobersdorf in Austria) was erected by Pousa Szák.

- The families from the Aba clan had an eagle on their coat-of-arms, and the Csáks adopted the lion.

- According to a 15th-century land-register, many ecclesiastic nobles in the Bishopric of Veszprém were descended from true noblemen who had sought the bishops' protection.

- The most powerful oligarch, Matthew Csák, dominated more than a dozen counties in northwestern Hungary; Ladislaus Kán was the actual ruler of Translyvnia; and Paul Šubić ruled Croatia and Dalmatia.

- The Styrian Hermann of Celje became the greatest landowner in Slavonia; the Pole Stibor of Stiboricz held 9 castles and 140 villages in northeastern Hungary.

- The Báthory, Perényi and Rozgonyi families were among the native beneficiaries of Sigismund's grants.

- Mircea I of Wallachia was awarded with Fogaras; Stefan Lazarević, Despot of Serbia, received more than a dozen of castles.

- Stephen Bánffy of Losonc held 68 villages in 1459, but the same villages were divided among his 14 descendants in 1526.

- From among the 36 wealthiest families of the late 1430s, 27 families survived till 1490, and only 8 families till 1570.

- The marriages of the children and grandchildren of Magdolna Székely by her three husbands established close family links between the Hungarian Széchy and Thurzó, the Croatian-Hungarian Zrinski, the Czech Kolowrat, Lobkowicz, Pernštejn, and Rožmberk, and the Austrian or German Arco, Salm and Ungnad families.

- The Tyrolian Count Pyrcho von Arco (who married the Hungarian Margit Széchy) were naturalized in Hungary in 1559; the Hungarian Baron Simon Forgách (who married the Austrian Ursula Pemfflinger) received citizenship in Lower Austria in 1568 and in Moravia in 1581.

- The Batthyány, Illésházy, Nádasdy and Thurzó families were the first converts.

- The former bodyguard, György Bessenyei, wrote pamphlets about the importance of education and the cultivation of the Hungarian language in the 1770s.

- Counts Emil Dessewffy, Antal Szécsen and György Apponyi were their leaders.

- Count Ferenc Zichy had a seat in the Imperial Council, Count Ferenc Nádasdy was made the Imperial Minister of Justice.

- The number of estates of between 1.15–5.75 km2 (280–1,420 acres) decreased from 20,000 to 10,000 from 1867 to 1900.

- In 1905, 88 counts and 66 barons had a seat in boards of directors.

- Henrik Lévay, who established the first Hungarian insurance company, was ennobled in 1868 and received the title baron in 1897; Zsigmond Kornfeld, who was the "Hungarian financial and industrial giant of the age", was created baron.

- The Chorins, Weisses and Kornfelds.

- Counts Gyula Dessewffy, Mihály Károlyi and Géza Teleki.

- Baron Zsigmond Kemény was imprisoned for initiating the execution of 191 Jews in Romania, although he had actually brought food to them.

- The Batthyány, Batthyány–Strattman, Erdődy, Esterházy and Zichy families.

References

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, pp. 71–73.

- Engel 2001, pp. 8, 17.

- Zimonyi 2016, pp. 160, 306–308, 359.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, pp. 76–77.

- Engel 2001, pp. 12–13.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, pp. 76–78.

- Lukačka 2011, pp. 31, 33–36.

- Georgescu 1991, p. 40.

- Pop 2013, p. 40.

- Wolf 2003, p. 329.

- Engel 2001, pp. 117–118.

- Engel 2001, pp. 8, 20.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 105.

- Engel 2001, p. 20.

- Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (ch. 39), p. 175.

- Bak 1993, p. 273.

- Wolf 2003, pp. 326–327.

- Wolf 2003, p. 327.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 107.

- Engel 2001, p. 16.

- Engel 2001, p. 17.

- Révész 2003, p. 341.

- Rady 2000, p. 12.

- Rady 2000, pp. 12–13.

- Rady 2000, pp. 12–13, 185 (notes 7–8).

- Engel 2001, p. 85.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 11.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, pp. 148–150.

- Wolf 2003, p. 330.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, pp. 149, 207–208.

- Engel 2001, p. 73.

- Rady 2000, pp. 18–19.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, pp. 149, 210.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 193.

- Rady 2000, pp. 16–17.

- Engel 2001, p. 40.

- Rady 2000, p. 28.

- Engel 2001, pp. 85–86.

- Rady 2000, pp. 28–29.

- Rady 2000, p. 29.

- Fügedi & Bak 2012, p. 324.

- Engel 2001, p. 86.

- Fügedi & Bak 2012, p. 326.

- Curta 2006, p. 267.

- Engel 2001, p. 33.

- Magaš 2007, p. 48.

- Curta 2006, p. 266.

- Magaš 2007, p. 51.

- Engel 2001, pp. 76–77.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 298.

- Rady 2000, pp. 25–26.

- Engel 2001, p. 87.

- Engel 2001, p. 80.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 299.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 297.

- Engel 2001, p. 81.

- Engel 2001, pp. 81, 87.

- Wolf 2003, p. 331.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 201.

- Engel 2001, pp. 71–72.

- Curta 2006, p. 401.

- Engel 2001, pp. 73–74.

- Rady 2000, pp. 128–129.

- Fügedi & Bak 2012, p. 328.

- Rady 2000, p. 129.

- Rady 2000, p. 31.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 286.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 20.

- Engel 2001, p. 93.

- Engel 2001, p. 92.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, pp. 426–427.

- Fügedi 1986a, p. 48.

- Rady 2000, p. 23.

- Engel 2001, pp. 86–87.

- Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 6.), p. 19.

- Rady 2000, p. 35.

- Rady 2000, p. 36.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 426.

- Fügedi 1998, p. 35.

- Engel 2001, p. 94.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 21.

- Engel 2001, p. 95.

- Rady 2000, pp. 40, 103.

- Engel 2001, p. 177.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 429.

- Engel 2001, p. 96.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 431.

- Rady 2000, p. 41.

- Kontler 1999, p. 78–80.

- Engel 2001, pp. 103–105.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 430.

- Fügedi 1986a, p. 51.

- Fügedi 1986a, pp. 52, 56.

- Fügedi 1986a, p. 56.

- Fügedi 1986a, p. 60.

- Fügedi 1986a, pp. 65, 73–74.

- Fügedi 1986a, p. 74.

- Engel 2001, p. 120.

- Rady 2000, p. 86.

- Engel 2001, p. 84.

- Rady 2000, p. 91.

- Engel 2001, pp. 104–105.

- Rady 2000, p. 83.

- Rady 2000, p. 81.

- Makkai 1994, pp. 208–209.

- Rady 2000, p. 46.

- Fügedi 1998, p. 28.

- Rady 2000, p. 48.

- Fügedi 1998, pp. 41–42.

- Fügedi 1986a, pp. 72–73.

- Fügedi 1986a, pp. 54, 82.

- Fügedi 1986a, p. 87.

- Rady 2000, pp. 112–113, 200.

- Fügedi 1986a, pp. 77–78.

- Fügedi 1986a, p. 78.

- Rady 2000, p. 110.

- Rady 2000, p. 112.

- Kontler 1999, p. 76.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 432.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, pp. 431–432.

- Rady 2000, p. 42.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 273.

- Engel 2001, p. 108.

- Engel 2001, p. 122.

- Engel 2001, p. 124.

- Engel 2001, p. 125.

- Engel 2001, pp. 126–127.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 34.

- Kontler 1999, p. 89.

- Engel 2001, pp. 141–142.

- Fügedi 1998, p. 52.

- Rady 2000, p. 108.

- Engel 2001, pp. 178–179.

- Engel 2001, p. 146.

- Engel 2001, p. 147.

- Engel 2001, p. 151.

- Rady 2000, p. 137.

- Engel 2001, pp. 151–153, 342.

- Rady 2000, pp. 146–147.

- Fügedi 1998, p. 34.

- Kontler 1999, p. 97.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 40.

- Engel 2001, p. 178.

- Engel 2001, p. 175.

- Pop 2013, pp. 198–212.

- Rady 2000, p. 89.

- Lukačka 2011, p. 37.

- Rady 2000, pp. 84, 89, 93.

- Rady 2000, pp. 89, 93.

- Pop 2013, pp. 470–471, 475.

- Pop 2013, pp. 256–257.

- Engel 2001, p. 165.

- Makkai 1994, pp. 191–192, 230.

- Rady 2000, pp. 59–60.

- Fügedi 1998, p. 45.

- Fügedi 1998, p. 47.

- Engel 2001, pp. 174–175.

- Rady 2000, p. 57.

- Engel 2001, p. 180.

- Engel 2001, pp. 179–180.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 42.

- Engel 2001, p. 199.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 102, 104–105.

- Engel 2001, pp. 204–205, 211–213.

- Engel 2001, pp. 343–344.

- Fügedi 1986a, p. 143.

- Engel 2001, p. 342.

- Fügedi 1986a, p. 123.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 44.

- Kontler 1999, p. 103.

- Engel 2001, p. 205.

- Kontler 1999, p. 104.

- Rady 2000, p. 150.

- Engel 2001, pp. 232–233, 337.

- Engel 2001, pp. 337–338.

- Engel 2001, p. 279.

- Kontler 1999, p. 112.

- Kontler 1999, p. 113.

- Engel 2001, p. 281.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 57.

- Kontler 1999, p. 116.

- Kontler 1999, p. 117.

- Engel 2001, pp. 288, 293.

- Engel 2001, p. 311.

- Fügedi 1986b, p. IV.14.

- Pálffy 2009, pp. 109–110.

- Engel 2001, p. 338.

- Engel 2001, pp. 338, 340–341.

- Engel 2001, p. 341.

- Engel 2001, p. 339.

- Kontler 1999, p. 134.

- Engel 2001, pp. 349–350.

- Engel 2001, p. 350.

- Kontler 1999, p. 135.

- Engel 2001, p. 351.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 70.

- The Customary Law of the Renowned Kingdom of Hungary in Three Parts (1517) (1.4.), p. 53.

- Fügedi 1998, pp. 32, 34.

- Fügedi 1998, p. 20.

- Fügedi 1998, pp. 21–22.

- The Customary Law of the Renowned Kingdom of Hungary in Three Parts (1517) (1.39.), p. 105.

- Fügedi 1998, p. 26.

- Fügedi 1998, p. 24.

- Fügedi 1998, p. 25.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 71.

- Kontler 1999, p. 129.

- Engel 2001, p. 357.

- Engel 2001, p. 362.

- Engel 2001, p. 363.

- Engel 2001, p. 364.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 72.

- Engel 2001, p. 370.

- Kontler 1999, p. 139.

- Szakály 1994, p. 85.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 83.

- Cartledge 2011, pp. 83, 94.

- Szakály 1994, p. 88.

- Szakály 1994, pp. 88–89.

- Szakály 1994, p. 92.

- Schimert 1995, p. 161.

- Pálffy 2009, p. 231.

- Schimert 1995, p. 162.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 91.

- Kontler 1999, p. 167.

- Szakály 1994, p. 89.

- Pálffy 2009, pp. 72, 86–88.

- Pálffy 2009, pp. 86, 366.

- Kontler 1999, p. 151.

- Murdock 2000, p. 12.

- Kontler 1999, p. 152.

- Murdock 2000, p. 20.

- Murdock 2000, p. 34.

- Kontler 1999, p. 156.

- Schimert 1995, p. 166.

- Schimert 1995, p. 158.

- Rady 2000, p. 155.

- Schimert 1995, p. 167.

- Pálffy 2009, p. 178.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 95.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 113.

- Kontler 1999, p. 183.

- Kontler 1999, p. 184.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 114.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 183–184.

- Á. Varga 1989, p. 188.

- Kontler 1999, p. 185.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 115.

- Schimert 1995, p. 170.

- Schimert 1995, pp. 170–171.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 116.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 123.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 127.

- Magaš 2007, pp. 187–188.

- Vermes 2014, p. 135.

- Schimert 1995, pp. 127, 152–154.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 196–197.

- Nakazawa 2007, p. 2007.

- Kováč 2011, p. 121.

- Kováč 2011, pp. 121–122.

- Kováč 2011, p. 122.

- Georgescu 1991, p. 89.

- Kontler 1999, p. 197.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 130.

- Vermes 2014, p. 33.

- Vermes 2014, pp. 33, 61.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 217–218.

- Schimert 1995, p. 176.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 151.

- Schimert 1995, p. 174.

- Vermes 2014, pp. 94, 136.

- Kontler 1999, p. 206.

- Kontler 1999, p. 218.

- Schimert 1995, pp. 175–176.

- Kontler 1999, p. 210.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 139.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 140.

- Kontler 1999, p. 217.

- Schimert 1995, p. 148.

- Schimert 1995, p. 149.

- Vermes 2014, p. 31.

- Vermes 2014, p. 32.

- Kontler 1999, p. 220.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 143.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 144–145.

- Kontler 1999, p. 221.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 221–222.

- Kontler 1999, p. 223.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 159.

- Cartledge 2011, pp. 159–160.

- Kontler 1999, p. 226.

- Kontler 1999, p. 228.

- Patai 2015, p. 373.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 162.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 164.

- Cartledge 2011, pp. 166–167.

- Kontler 1999, p. 235.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 168.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 179.

- Kontler 1999, p. 242.

- Kontler 1999, p. 179.

- Magaš 2007, p. 202.

- Nakazawa 2007, p. 160.

- Kontler 1999, p. 247.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 191.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 194.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 196.

- Á. Varga 1989, p. 189.

- Kontler 1999, p. 248.

- Kontler 1999, p. 251.

- Nakazawa 2007, p. 163.

- Kováč 2011, p. 126.

- Georgescu 1991, p. 155.

- Kontler 1999, p. 250.

- Magaš 2007, p. 230.

- Kontler 1999, p. 253.

- Kontler 1999, p. 257.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 217.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 219.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 221.

- Cartledge 2011, pp. 220–221.

- Kontler 1999, p. 266.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 222.

- Kontler 1999, p. 270.

- Kontler 1999, p. 268.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 270–271.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 231.

- Georgescu 1991, p. 158.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 232.

- Magaš 2007, pp. 297–298.

- Kontler 1999, p. 281.

- Kontler 1999, p. 305.

- Kontler 1999, p. 285.

- Taylor 1976, p. 185.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 257.

- Taylor 1976, p. 186.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 255.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 256.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 258.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 259.

- Patai 2015, pp. 290–292, 369–370.

- Taylor 1976, pp. 244–251.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 328–329.

- Cartledge 2011, pp. 303–304.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 304.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 305.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 333–334.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 307.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 308.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 309.

- Kontler 1999, p. 338.

- Kontler 1999, p. 339.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 339, 345.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 334.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 352.

- Kontler 1999, p. 345.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 345–346.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 351.

- Kontler 1999, p. 347.

- Kontler 1999, p. 353.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 340.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 353.

- Kontler 1999, p. 348.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 354.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 347–348, 365.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 377–378.

- Cartledge 2011, pp. 395–396.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 398.

- Kontler 1999, p. 386.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 409.

- Kontler 1999, p. 391.

- Gudenus & Szentirmay 1989, p. 43.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 411.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 412.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 414.

- Kontler 1999, p. 394.

- Gudenus & Szentirmay 1989, p. 75.

- Gudenus & Szentirmay 1989, p. 73.

- Cartledge 2011, pp. 417–418.

- Cartledge 2011, p. 421.

- Gudenus & Szentirmay 1989, p. 28.

- Gudenus & Szentirmay 1989, pp. 27–28.

- Gudenus & Szentirmay 1989, p. 27.

- 2007. évi LXXXII. törvény (in Hungarian)

- Templomot, iskolát a magyarságért Archived 2010-10-02 at the Wayback Machine (in Hungarian)

- T/1954 Az egyes címek és rangok megszüntetéséről szóló 1947. évi IV. törvény módosításáról (in Hungarian) Archived 2012-03-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Iromány adatai: 2010– T/1954 Az egyes címek és rangok megszüntetéséről szóló 1947. évi IV. törvény módosításáról. (in Hungarian) Last access: March 05, 2011

- Alkotmány: újjászületnek a vármegyék (in Hungarian)

Sources

Primary sources

- Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (Edited, Translated and Annotated by Martyn Rady and László Veszprémy) (2010). In: Rady, Martyn; Veszprémy, László; Bak, János M. (2010); Anonymus and Master Roger; CEU Press; ISBN 978-963-9776-95-1.

- Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (Greek text edited by Gyula Moravcsik, English translation by Romillyi J. H. Jenkins) (1967). Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 0-88402-021-5.

- Simon of Kéza: The Deeds of the Hungarians (Edited and translated by László Veszprémy and Frank Schaer with a study by Jenő Szűcs) (1999). CEU Press. ISBN 963-9116-31-9.

- The Customary Law of the Renowned Kingdom of Hungary in Three Parts (1517) (Edited and translated by János M. Bak, Péter Banyó and Martyn Rady, with an introductory study by László Péter) (2005). Charles Schlacks, Jr.; Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University. ISBN 1-884445-40-3.

- The Laws of the Medieval Kingdom of Hungary, 1000–1301 (Translated and edited by János M. Bak, György Bónis, James Ross Sweeney with an essay on previous editions by Andor Czizmadia, Second revised edition, In collaboration with Leslie S. Domonkos) (1999). Charles Schlacks, Jr. Publishers.

Secondary sources

- Á. Varga, László (1989). "hitbizomány [fee tail]". In Bán, Péter (ed.). Magyar történelmi fogalomtár, A–L [Thesaurus of Hungarian History]. Gondolat. pp. 188–189. ISBN 963-282-203-X.