Rhaetian language

Rhaetic or Raetic (/ˈriːtɪk/), also known as Rhaetian,[2] was a language spoken in the ancient region of Rhaetia in the Eastern Alps in pre-Roman and Roman times. It is documented by around 280 texts dated from the 5th up until the 1st century BC, which were found through Northern Italy, Southern Germany, Eastern Switzerland, Slovenia and Western Austria,[3][4] in two variants of the Old Italic scripts.[5]

| Rhaetic | |

|---|---|

| Raetic | |

| Native to | Ancient Rhaetia |

| Region | Eastern Alps |

| Era | Early 1st millennium BC to 1st century BC[1] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | xrr |

xrr | |

| Glottolog | raet1238 |

| |

The ancient Rhaetic language is not to be confused with the modern Romance languages of the same Alpine region, known as Rhaeto-Romance.

Classification

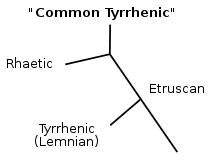

The German linguist Helmut Rix proposed in 1998 that Rhaetic, along with Etruscan, was a member of a language family he called Tyrrhenian, and which was possibly influenced by neighboring Indo-European languages.[7][8] Robert S. P. Beekes likewise does not consider it Indo-European.[9] Howard Hayes Scullard (1967), on the contrary, suggested it to be an Indo-European language, with links to Illyrian and Celtic.[10] Nevertheless, most scholars now think that Rhaetic is closely related to Etruscan within the Tyrrhenian grouping.[11]

Rix's Tyrsenian family is supported by a number of linguists such as Stefan Schumacher,[12][13] Carlo De Simone,[14] Norbert Oettinger,[15] Simona Marchesini,[6] or Rex E. Wallace.[16] Common features between Etruscan, Rhaetic, and Lemnian have been observed in morphology, phonology, and syntax. On the other hand, few lexical correspondences are documented, at least partly due to the scanty number of Rhaetic and Lemnian texts and possibly to the early date at which the languages split.[17][18] The Tyrsenian family (or Common Tyrrhenic) is often considered to be Paleo-European and to predate the arrival of Indo-European languages in southern Europe.[19]

History

According to L. Bouke van der Meer, Rhaetic could have developed from Etruscan from around 900 BCE or even earlier, and no later than 700 BCE, since divergences are already present in the oldest Etruscan and Rhaetic inscriptions, such as in the grammatical voices of past tenses or in the endings of male gentilicia. Around 600 BCE, the Rhaeti became isolated from the Etruscan area, probably by the Celts, thus limiting contacts between the two languages.[11]

The language is documented in Northern Italy between the 5th and the 1st centuries BCE by about 280 texts, in an area corresponding to the Fritzens-Sanzeno and Magrè cultures.[4] It is clear that in the centuries leading up to Roman imperial times, the Rhaetians had at least come under Etruscan influence, as the Rhaetic inscriptions are written in what appears to be a northern variant of the Etruscan alphabet. The ancient Roman sources mention the Rhaetic people as being reputedly of Etruscan origin, so there may at least have been some ethnic Etruscans who had settled in the region by that time.

In his Natural History (1st century CE), Pliny wrote about Alpine peoples:

... adjoining these (the Noricans) are the Rhaeti and Vindelici. All are divided into several states.[lower-alpha 1] The Rhaeti are believed to be people of Tuscan race[lower-alpha 2] driven out by the Gauls; their leader was named Rhaetus.[20]

Pliny's comment on a leader named Rhaetus is typical of mythologized origins of ancient peoples, and not necessarily reliable. The name of the Venetic goddess Reitia has commonly been discerned in the Rhaetic finds, but the two names do not seem to be linked. The spelling as Raet- is found in inscriptions, while Rhaet- was used in Roman manuscripts; it is unclear whether this Rh represents an accurate transcription of an aspirated R in Rhaetic, or is merely an error.

In popular culture

An altered variety of Rhaetic is "spoken" in Felix Randau's 2017 film Iceman.[21]

See also

Notes

- in multas civitates divisi.

- Tuscorum prolem (genitive case followed by accusative case): "offshoot of the Tuscans."

References

- Rhaetic at MultiTree on the Linguist List

- Silvestri, M.; Tomezzoli, G. (2007). Linguistic distances between Rhaetian, Venetic, Latin and Slovenian languages (PDF). Proc. Int'l Topical Conf. Origin of Europeans. pp. 184–190.

- "The Raetic alphabets".

- Marchesini, Simona. "Raetic – writing systems". Mnamon.

- Salomon 2020.

- Carlo de Simone, Simona Marchesini (Eds), La lamina di Demlfeld [= Mediterranea. Quaderni annuali dell'Istituto di Studi sulle Civiltà italiche e del Mediterraneo antico del Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche. Supplemento 8], Pisa – Roma: 2013.

- Rix 1998.

- Schumacher 1998.

- Robert S.P. Beekes, Comparative Indo-European Linguistics: an introduction, 2nd ed. 2011:26: "It seems improbable that Rhaetic (spoken from Lake Garda to the Inn valley) is Indo-European, as it appears to contain Etruscan elements."

- Scullard 1967, p. 43.

- Van der Meer 2004.

- Schumacher 1999.

- Schumacher 2004.

- de Simone Carlo (2009) La nuova iscrizione tirsenica di Efestia in Aglaia Archontidou, Carlo de Simone, Emanuele Greco (Eds.), Gli scavi di Efestia e la nuova iscrizione ‘tirsenica’, TRIPODES 11, 2009, pp. 3-58. Vol. 11 pp. 3-58 (Italian)

- Oettinger, Norbert (2010) "Seevölker und Etrusker", in Yoram Cohen, Amir Gilan, and Jared L. Miller (eds.) Pax Hethitica Studies on the Hittites and their Neighbours in Honour of Itamar Singer (in German), Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 233–246

- Wallace, Rex E. (2018), "Lemnian language", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.8222, ISBN 978-0-19-938113-5

- Simona Marchesini (translation by Melanie Rockenhaus) (2013). "Raetic (languages)". Mnamon - Ancient Writing Systems in the Mediterranean. Scuola Normale Superiore. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- Kluge Sindy, Salomon Corinna, Schumacher Stefan (2013–2018). "Raetica". Thesaurus Inscriptionum Raeticarum. Department of Linguistics, University of Vienna. Retrieved 26 July 2018.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Mellaart, James (1975), "The Neolithic of the Near East" (Thames and Hudson)

- Pliny. "XX". Naturalis Historia (in Latin). III. Translated by Rackham, H. Loeb.

- https://www.economist.com/blogs/prospero/2017/08/bewitching-and-bewildering

Sources

- de Simone, Carlo; Marchesini, Simona (2013). La lamina di Demlfeld. Rome-Pisa: Fabrizio Serra Editore.

- Morandi, Alessandro (1999). "Il cippo di Castelciès nell'epigrafia retica". Studia archaeologica. Rome: Bretschneider. 103.

- Prosdocimi, Aldo L. (2003-4). "Sulla formazione dell'alfabeto runico. Promessa di novità documentali forse decisive". Archivio per l'Alto Adige 97–98.427–440

- Rix, Helmut (1998). Rätisch und Etruskisch [Rhaetian & Etruscan]. Vorträge und kleinere Schriften (in German). Innsbruck: Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Sprachwissenschaft: Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck.

- Roncador, Rosa; Marchesini, Simona (2015). Monumenta Linguae Raeticae. Rome: Scienze e Lettere.

- Schumacher, Stefan (1998). "Sprachliche Gemeinsamkeiten zwischen Rätisch und Etruskisch". Der Schlern (in German). 72: 90–114.

- Schumacher, Stefan (1999). "Die Raetischen Inschriften: Gegenwärtiger Forschungsstand, spezifische Probleme und Zukunfstaussichten". I Reti / Die Räter, Atti del simposio 23-25 settembre 1993, Castello di Stenico, Trento, Archeologia delle Alpi, a cura di G. Ciurletti. F. Marzatico Archaoalp. pp. 334–369.

- Schumacher, Stefan (2004) [1992]. Die rätischen Inschriften. Geschichte und heutiger Stand der Forschung. Sonderheft (2nd ed.). Innsbruck: Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Kulturwissenschaft: Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck.

- Scullard, HH (1967). The Etruscan Cities and Rome. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Van der Meer, L. Bouke (2004). "Etruscan origins. Language and archaeology". BABesch. 79: 51–57.

Further reading

- Salomon, Corinna (2020). "Raetic". Palaeohispanica. Revista sobre lenguas y culturas de la Hispania Antigua (20): 263–298. doi:10.36707/palaeohispanica.v0i20.380. ISSN 1578-5386.

External links

- Schumacher, Stefan; Kluge, Sindy (2013–2017). Salomon, Corinna (ed.). "Thesaurus Inscriptionum Raeticarum". Department of Linguistics. of the University of Vienna.

- Zavaroni, Adolfo, Rhaetic inscriptions, Tripod.