Ainu languages

The Ainu languages /ˈaɪnuː/ (Ainu: アィヌ・イタㇰ, 'Aynu-itak'; Japanese: アイヌ語, 'Ainu-go'),[3] sometimes also known as Ainuic, are a small language family, often portrayed as a language isolate, historically spoken by the Ainu people of northern Japan and neighboring islands.

| Ainu | |

|---|---|

| Ainuic | |

| Ethnicity | 25,000 (1986) to ca. 200,000 (no date) Ainu people[1] |

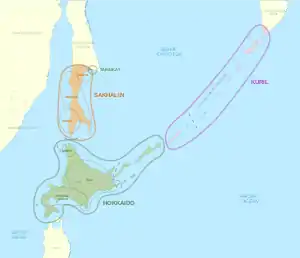

| Geographic distribution | Currently only Hokkaido; formerly also southern and central Sakhalin, the Kuril Islands and possibly northern Honshu |

| Linguistic classification | primary language family |

| Subdivisions | |

| Glottolog | ainu1252 |

| ELP | Ainu (Japan)[2] |

Map of pre-1945 distribution of Ainu languages and dialects | |

The primary varieties of Ainu are alternately considered a group of closely related languages[4] or divergent dialects of a single language isolate. The only surviving variety is Hokkaido Ainu, which UNESCO lists as critically endangered. Sakhalin Ainu and Kuril Ainu are now extinct. Toponymic evidence suggests Ainu was once spoken in northern Honshu. No genealogical relationship between Ainu and any other language family has been demonstrated, despite numerous attempts.

Varieties

Recognition of the different varieties of Ainu spoken throughout northern Japan and its surrounding islands in academia varies. Shibatani (1990:9) and Piłsudski (1998:2) both speak of "Ainu languages" when comparing the varieties of language spoken in Hokkaidō and Sakhalin; however, Vovin (1993) speaks only of "dialects". Refsing (1986) says Hokkaidō and Sakhalin Ainu were not mutually intelligible. Hattori (1964) considered Ainu data from 19 regions of Hokkaidō and Sakhalin, and found the primary division to lie between the two islands.

Kuril Ainu

Data on Kuril Ainu is scarce, but it is thought to have been as divergent as Sakhalin and Hokkaidō.

Sakhalin Ainu

In Sakhalin Ainu, an eastern coastal dialect of Taraika (near modern Gastello (Poronaysk)) was quite divergent from the other localities. The Raychishka dialect, on the western coast near modern Uglegorsk, is the best documented and has a dedicated grammatical description. Take Asai, the last speaker of Sakhalin Ainu, died in 1994.[5] The Sakhalin Ainu dialects had long vowels and a final -h phoneme, which they pronounced as /x/.

Hokkaidō Ainu

Hokkaidō Ainu clustered into several dialects with substantial differences between them: the 'neck' of the island (Oshima County, data from Oshamambe and Yakumo); the "classical" Ainu of central Hokkaidō around Sapporo and the southern coast (Iburi and Hidaka counties, data from Horobetsu, Biratori, Nukkibetsu and Niikappu; historical records from Ishikari County and Sapporo show that these were similar); Samani (on the southeastern cape in Hidaka, but perhaps closest to the northeastern dialect); the northeast (data from Obihiro, Kushiro and Bihoro); the north-central dialect (Kamikawa County, data from Asahikawa and Nayoro) and Sōya (on the northwestern cape), which was closest of all Hokkaidō varieties to Sakhalin Ainu. Most texts and grammatical descriptions we have of Ainu cover the Central Hokkaidō dialect.

Scant data from Western voyages at the turn of the 19th–20th century (Tamura 2000) suggest there was also great diversity in northern Sakhalin, which was not sampled by Hattori.

Classification

Vovin (1993) splits Ainu "dialects" as follows (Vovin 1993:157):

- Proto-Ainu

- Proto-Hokkaido–Kuril

- Proto-Sakhalin

External relationships

No genealogical relationship between Ainu and any other language family has been demonstrated, despite numerous attempts. Thus, it is a language isolate. Ainu is sometimes grouped with the Paleosiberian languages, but this is only a geographic blanket term for several unrelated language families that were present in Siberia before the advances of Turkic and Tungusic languages there.

A study by Lee and Hasegawa of Waseda University found evidence that the Ainu language and the early Ainu-speakers originated from the Northeast Asian/Okhotsk population, which established themselves in northern Hokkaido and expanded into large parts of Honshu and the Kurils and had significant impact on the formation of the incipient Jōmon culture and ethnicities.[6]

The Ainu languages share a noteworthy amount of vocabulary (especially fish names) with several Northeast Asian languages, including Nivkh, Tungusic, Mongolic, and Chukotko-Kamchatkan. While linguistic evidence point to an origin of these words among the Ainu languages, its spread and how this words arrived into other languages will possibly remain a mystery.[7]

The most frequent proposals for relatives of Ainu are given below:

Altaic

John C. Street (1962) proposed linking Ainu, Korean, and Japanese in one family and Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic in another, with the two families linked in a common "North Asiatic" family. Street's grouping was an extension of the Altaic hypothesis, which at the time linked Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic, sometimes adding Korean; today Altaic sometimes includes Korean and rarely Japanese but not Ainu (Georg et al. 1999).

From a perspective more centered on Ainu, James Patrie (1982) adopted the same grouping, namely Ainu–Korean–Japanese and Turkic–Mongolic–Tungusic, with these two families linked in a common family, as in Street's "North Asiatic".

Joseph Greenberg (2000–2002) likewise classified Ainu with Korean and Japanese. He regarded "Korean–Japanese-Ainu" as forming a branch of his proposed Eurasiatic language family. Greenberg did not hold Korean–Japanese–Ainu to have an especially close relationship with Turkic–Mongolic–Tungusic within this family.

The Altaic hypothesis is now rejected by the scholarly mainstream.[8][9][10][11]

Austroasiatic

Shafer (1965) presented evidence suggesting a distant connection with the Austroasiatic languages, which include many of the indigenous languages of Southeast Asia. Vovin (1992) presented his reconstruction of Proto-Ainu with evidence, in the form of proposed sound changes and cognates, of a relationship with Austroasiatic. In Vovin (1993), he still regarded this hypothesis as preliminary.

Language contact with the Nivkhs

The Ainu appear to have experienced intensive contact with the Nivkhs during the course of their history. It is not known to what extent this has affected the language. Linguists believe the vocabulary shared between Ainu and Nivkh (historically spoken in the northern half of Sakhalin and on the Asian mainland facing it) is due to borrowing.[12]

Language contact with the Japanese

The Ainu came into extensive contact with the Japanese in 14th century. Analytic grammatical constructions acquired or transformed in Ainu were probably due to contact with the Japanese language. A large number of Japanese loanwords were borrowed into Ainu and to a smaller extent vice versa.[13] There are also a great number of loanwords from the Japanese language in various stages of its development to Hokkaidō Ainu, and a smaller number of loanwords from Ainu into Japanese, particularly animal names such as 'rakko' ("sea otter"; Ainu 'rakko'), 'tonakai' ("reindeer"; Ainu 'tunakkay'), and 'shishamo' (a fish, Spirinchus lanceolatus; Ainu 'susam'). Due to the low status of Ainu in Japan, many ancient loanwords may be ignored or undetected, but there is evidence of an older substrate, where older Japanese words which have no clear etymology appear related to Ainu words which do. An example is modern Japanese sake or shake, meaning "salmon", probably from the Ainu sak ipe or shak embe for "salmon", literally "summer food".

Other proposals

A small number of linguists suggested a relation between Ainu and Indo-European languages, based on racial theories regarding the origin of the Ainu people. The theory of an Indo-European—Ainu relation was popular until 1960, later linguists dismissed it and did not follow the theory any more and concentrated on more local language families.[14][15]

Tambotsev (2008) proposes that Ainu is typologically most similar to Native American languages and suggests that further research is needed to establish a genetic relationship between these languages.[16]

Geography

Until the 20th century, Ainu languages were spoken throughout the southern half of the island of Sakhalin and by small numbers of people in the Kuril Islands. Only the Hokkaido variant survives, with the last speaker of Sakhalin Ainu having died in 1994.

Some linguists noted that the Ainu language was an important lingua franca on Sakhalin. Asahi (2005) reported that the status of the Ainu language was rather high and was also used by early Russian and Japanese administrative officials to communicate with each other and with the indigenous people.[17]

Ainu on mainland Japan

It is occasionally suggested that Ainu was the language of the indigenous Emishi people of the northern part of the main Japanese island of Honshu.[lower-alpha 1] The main evidence for this is the presence of placenames that appear to be of Ainu origin in both locations. For example, the -betsu common to many northern Japanese place names is known to derive from the Ainu word 'pet' ("river") in Hokkaidō, and the same is suspected of similar names ending in -be in northern Honshū and Chūbu, such as the Kurobe and Oyabe rivers in Toyama Prefecture.[18] Other place names in Kantō and Chūbu, such as Mount Ashigara (Kanagawa–Shizuoka), Musashi (modern Tokyo), Keta Shrine (Toyama), and the Noto Peninsula, have no explanation in Japanese, but do in Ainu. The traditional matagi hunters of the mountain forests of Tōhoku retain Ainu words in their hunting vocabulary.[19][20]

However, more recent studies and evidence make this scenario unlikely. A study by Lee and Hasegawa from the Waseda University using linguistic, archeologic and genetic evidence, found that the Ainu are significantly linked to the Okhotsk culture. Lee and Hasegawa found that proto-Ainu expanded from northern Hokkaido to the Kurils, Kamchatka as well as northern Honshu. They further propose that the Ainu language, or its ancestral form "Proto-Ainu", comes from the Okhotsk culture and people of northern Hokkaido.[21] The Emishi are recently often suggested to have spoken a language unrelated to Ainu. A recent proposal found convincing evidence that the Emishi spoke a divergent Japonic language, most closely related to the historical Izumo dialect.[22]

The linguist and historian Joran Smale (2014) similarly found that the Ainu language likely originated from the Okhotsk people, which had strong cultural influence on the "Epi-Jōmon" of southern Hokkaido and northern Honshu, but that the Ainu people themselves formed from the combination of both ancient groups. Additionally, he notes that the historical distribution of Ainu dialects correspond to the distribution of the Okhotsk culture.[23]

Notes

- Ainu may also have been the language of one of the peoples known as 'Emishi'; it is not known that the Emishi were a single ethnicity.

References

- Poisson, Barbara Aoki (2002). The Ainu of Japan. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications.

- Endangered Languages Project data for Ainu (Japan).

- Bauer, Laurie (2007). The Linguistics Student's Handbook. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forke, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2020). "Ainu". Glottolog 4.3.

- Piłsudski, Bronisław; Alfred F. Majewicz (2004). The Collected Works of Bronisław Piłsudski. Trends in Linguistics Series. 3. Walter de Gruyter. p. 600. ISBN 9783110176148. Retrieved 2012-05-22.

- Lee, Hasegawa, Sean, Toshikazu (April 2013). "Evolution of the Ainu Language in Space and Time".

In this paper, we reconstructed spatiotemporal evolution of 19 Ainu language varieties, and the results are in strong agreement with the hypothesis that a recent population expansion of the Okhotsk people played a critical role in shaping the Ainu people and their culture. Together with the recent archaeological, biological and cultural evidence, our phylogeographic reconstruction of the Ainu language strongly suggests that the conventional dual-structure model must be refined to explain these new bodies of evidence. The case of the Ainu language origin we report here also contributes additional detail to the global pattern of language evolution, and our language phylogeny might also provide a basis for making further inferences about the cultural dynamics of the Ainu speakers [44,45].

- Alonso de la Fuente, Jose. "Hokkaidō "Ainu susam" and Japanese "shishamo"". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "While 'Altaic' is repeated in encyclopedias and handbooks most specialists in these languages no longer believe that the three traditional supposed Altaic groups, Turkic, Mongolian and Tungusic, are related." Lyle Campbell & Mauricio J. Mixco, A Glossary of Historical Linguistics (2007, University of Utah Press), pg. 7.

- "When cognates proved not to be valid, Altaic was abandoned, and the received view now is that Turkic, Mongolian, and Tungusic are unrelated." Johanna Nichols, Linguistic Diversity in Space and Time (1992, Chicago), pg. 4.

- "Careful examination indicates that the established families, Turkic, Mongolian, and Tungusic, form a linguistic area (called Altaic)...Sufficient criteria have not been given that would justify talking of a genetic relationship here." R.M.W. Dixon, The Rise and Fall of Languages (1997, Cambridge), pg. 32.

- "...[T]his selection of features does not provide good evidence for common descent" and "we can observe convergence rather than divergence between Turkic and Mongolic languages—a pattern than is easily explainable by borrowing and diffusion rather than common descent", Asya Pereltsvaig, Languages of the World, An Introduction (2012, Cambridge) has a good discussion of the Altaic hypothesis (pp. 211–216).

- Vovin, Alexander. 2016. "On the Linguistic Prehistory of Hokkaidō." In Crosslinguistics and linguistic crossings in Northeast Asia: papers on the languages of Sakhalin and adjacent regions (Studia Orientalia 117).

- Tranter, Nicolas (25 June 2012). The Languages of Japan and Korea. Routledge. ISBN 9781136446580. Retrieved 29 March 2019 – via Google Books.

- Zgusta, Richard (2015-07-10). The Peoples of Northeast Asia through Time: Precolonial Ethnic and Cultural Processes along the Coast between Hokkaido and the Bering Strait. BRILL. ISBN 9789004300439.

- Refsing, edited in 5 volumes by Kirsten. "Origins of the Ainu language : the Ainu Indo-European controversy". 新潟大学OPAC. Retrieved 2019-09-17.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Tambovtsev, Yuri (2008). "The phono-typological distances between Ainu and the other world languages as a clue for closeness of languages" (PDF). Asian and African Studies. 17 (1): 40–62. Retrieved 2019-09-30.

- Yoshiko Yamada "A Preliminary Study of Language Contact around Uilta in Sakhalin." Hokkaido University 2010

- Miller 1967:239, Shibatani 1990:3, Vovin 2008

- Kudō Masaki (1989:134). Jōsaku to emishi. Kōkogaku Library #51. New Science Press.

- Tanigawa, Ken'ichi (1980:324–325). Collected works, vol. 1.

- Lee, Hasegawa, Sean, Toshikazu (April 2013). "Evolution of the Ainu Language in Space and Time".

In this paper, we reconstructed spatiotemporal evolution of 19 Ainu language varieties, and the results are in strong agreement with the hypothesis that a recent population expansion of the Okhotsk people played a critical role in shaping the Ainu people and their culture. Together with the recent archaeological, biological and cultural evidence, our phylogeographic reconstruction of the Ainu language strongly suggests that the conventional dual-structure model must be refined to explain these new bodies of evidence. The case of the Ainu language origin we report here also contributes additional detail to the global pattern of language evolution, and our language phylogeny might also provide a basis for making further inferences about the cultural dynamics of the Ainu speakers [44,45].

- Boer, Elisabeth de; Yang, Melinda A.; Kawagoe, Aileen; Barnes, Gina L. (2020/ed). "Japan considered from the hypothesis of farmer/language spread". Evolutionary Human Sciences. 2. doi:10.1017/ehs.2020.7. ISSN 2513-843X. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Joran Smale "A Peer Polity Interaction approach to the interaction, exchange and decline of a Northeast-Asian maritime culture on Hokkaido, Japan" Leiden University, Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden, June 2014 Quote: "Further analysis of the origins of Ainu language and the earliest places names of their settlements might provide some insight into the heritage of an Okhotsk language."

Bibliography

- Bugaeva, Anna (2010). "Internet applications for endangered languages: A talking dictionary of Ainu". Waseda Institute for Advanced Study Research Bulletin. 3: 73–81.

- Hattori, Shirō, ed. (1964). Bunrui Ainugo hōgen jiten [An Ainu dialect dictionary with Ainu, Japanese, and English indexes]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

- Miller, Roy Andrew (1967). The Japanese Language. Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle.

- Murasaki, Kyōko (1977). Karafuto Ainugo: Sakhalin Rayciska Ainu Dialect—Texts and Glossary. Tokyo: Kokushokankōkai.

- Murasaki, Kyōko (1978). Karafuto Ainugo: Sakhalin Rayciska Ainu Dialect—Grammar. Tokyo: Kokushokankōkai.

- Piłsudski, Bronisław (1998). Alfred F. Majewicz (ed.). The Aborigines of Sakhalin. The Collected Works of Bronisław Piłsudski. I. Berlin-New York: Walter de Gruyter. p. 792. ISBN 978-3-11-010928-3.

- Refsing, Kirsten (1986). The Ainu Language: The Morphology and Syntax of the Shizunai Dialect. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. ISBN 87-7288-020-1.

- Refsing, Kirsten (1996). Early European Writings on the Ainu Language. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7007-0400-2.

- Shibatani, Masayoshi (1990). The Languages of Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36918-5.

- Tamura, Suzuko (2000). The Ainu Language. Tokyo: Sanseido. ISBN 4-385-35976-8.

- Vovin, Alexander (2008). "Man'yōshū to Fudoki ni Mirareru Fushigina Kotoba to Jōdai Nihon Retto ni Okeru Ainugo no Bunpu" [Strange Words in the Man'yoshū and the Fudoki and the Distribution of the Ainu Language in the Japanese Islands in Prehistory] (PDF). Kokusai Nihon Bunka Kenkyū Sentā. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-11. Retrieved 2011-01-17. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Vovin, Alexander (1992). "The origins of the Ainu language" (PDF). The Third International Symposium on Language and Linguistics: 672–686.

- Vovin, Alexander (1993). A Reconstruction of Proto-Ainu. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09905-0.

- Proposed classifications

- Bengtson, John D. (2006). "A Multilateral Look at Greater Austric". Mother Tongue. 11: 219–258.

- Georg, Stefan; Michalove, Peter A.; Ramer, Alexis Manaster; Sidwell, Paul J. (1999). "Telling general linguists about Altaic". Journal of Linguistics. 35: 65–98. doi:10.1017/s0022226798007312.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. (2000–2002). Indo-European and Its Closest Relatives. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3812-5.

- Patrie, James (1982). The Genetic Relationship of the Ainu Language. Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii. ISBN 978-0-8248-0724-5.

- Shafer, R. (1965). "Studies in Austroasian II". Studia Orientalia. 30 (5).

- Street, John C. (1962). "Review of N. Poppe, Vergleichende Grammatik der altaischen Sprachen, Teil I (1960)". Language. 38 (1): 92–98. doi:10.2307/411195. JSTOR 411195.

Further reading

- John Batchelor (1905). An Ainu–English–Japanese Dictionary, including A Grammar of the Ainu Language (2, reprint ed.). Tokyo: Methodist Publishing House; London, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. 525. Retrieved March 1, 2012. (Digitized by the University of Michigan December 8, 2006)

- Basil Hall Chamberlain; John Batchelor (1887). Ainu grammar. Tokyo: Imperial University. p. 174. Retrieved March 1, 2012. (Digitized by Harvard University November 30, 2007)

- Batchelor, John (1897). Chikoro Utarapa Ne Yesu Kiristo Ashiri Aeuitaknup (in Ainu). Yokohama Bunsha. p. 706. Retrieved March 1, 2012. (Harvard University) (Digitized October 8, 2008)

- Batchelor, John (1896). Chikoro Utarapa ne Yesu Kiristo Ashiri Aeuitaknup (in Ainu). Printed for the Bible Societies' Committee for Japan by the Yokohama Bunsha. p. 313. Retrieved March 1, 2012. (Harvard University) (Digitized October 8, 2008 )

- British and Foreign Bible Society (1891). Chikoro utarapa ne Yesu Kiristo ashiri ekambakte-i Markos, Roukos, Newa Yoanne: orowa no asange ashkanne pirika shongo/St Mark, St Luke and St John in Ainu (in Ainu). London: British and Foreign Bible Society. p. 348. Retrieved March 1, 2012. (Harvard University) (Digitized June 9, 2008)

- Kyōsuke Kindaichi (1936). アイヌ語法概說. 岩波書店. p. 230. Retrieved March 1, 2012. (Compiled by Mashiho Chiri) (University of Michigan) (Digitized August 15, 2006)

- Miyake, Marc. 2010. Is the itak an isolate?

See also

External links

| Wiktionary has a list of reconstructed forms at Appendix:Proto-Ainu reconstructions |

| Ainu languages test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Ainu phrasebook. |

- Literature and materials for learning Ainu

- The Book of Common Prayer in Ainu, translated by John Batchelor, digitized by Richard Mammana and Charles Wohlers

- Institute for the Study of Languages and Cultures of Ainu in Samani, Hokkaido

- A Grammar of the Ainu Language by John Batchelor

- An Ainu-English-Japanese Dictionary, including A Grammar of the Ainu Language by John Batchelor

- "The 'Greater Austric' hypothesis" by John Bengtson (undated)

- Ainu for Beginners by Kane Kumagai, translated by Yongdeok Cho

- (in Japanese) Radio lessons on Ainu language presented by Sapporo TV

- A talking dictionary of Ainu: a new version of Kanazawa's Ainu conversational dictionary, with recordings of Mrs. Setsu Kurokawa

.svg.png.webp)