Roman funerary practices

Roman funerary practices include the Ancient Romans' religious rituals concerning funerals, cremations, and burials. They were part of time-hallowed tradition (Latin: mos maiorum), the unwritten code from which Romans derived their social norms.[1]

| Religion in ancient Rome |

|---|

|

| Practices and beliefs |

| Priesthoods |

| Deities |

Deified emperors: |

| Related topics |

Funeral rites, especially processions and public eulogies, gave the family opportunity to publicly celebrate the life and deeds of the deceased, their ancestors, and their own standing in the community. Sometimes the political elite gave costly public feasts, games and popular entertainments after family funerals, to honour the departed and to maintain a high public profile and reputation for generosity among the people. Even the simplest funerals of Rome's citizen and free majority could be very costly, relative to income. A professsional class of expert undertakers and their staff was available to manage the funeral rites and disposal. Among the elite, funeral displays and expenses were constrained by sumptuary laws, designed to reduce class envy and consequent social conflict.

Roman cemeteries were located outside the sacred boundary (pomerium) of towns and cities. They were visited regularly with offerings of food and wine, and special observances during Roman festivals in honor of the dead; correct funerary observances and continuity of care ensured that the shade of the departed was well disposed towards the living.

Funeral monuments and tombs lined some of the major roads leading to and from major settlements throughout the Roman Republic and Roman Empire, and their inscriptions are an important source of information for individuals, families and significant events, often otherwise unknown, or only partly known through written historical sources. A Roman sarcophagus could be an elaborately crafted art work, decorated with relief sculpture depicting a scene that was allegorical, mythological, or historical, or a scene from everyday life. Although funerals were primarily a concern of the family, which was of paramount importance in Roman society, those who lacked the support of an extended family usually belonged to guilds or collegia which provided funeral services for members.

Romans initially inhumated their dead, but they shifted to cremation in the middle of the Republic. It remained the most common funerary practice until the middle of the Empire, when they returned to inhumation.

Care of the dead

In Greco-Roman antiquity, the bodies of the dead were regarded as polluting.[2] At the same time, loving duty toward one's ancestors (pietas) was a fundamental part of ancient Roman culture.[3] The care of the dead negotiated these two emotionally opposed attitudes. In a society with a very high mortality rate, disposal of the dead was an essential, practical and often urgent obligation for relatives, and for civic and religious authorities.[4] Treatment of the dead was regulated by custom, and by civil and religious law, administered by specialised magistrates, professional bodies of undertakers and their assistants, and the family, friends or colleagues of the deceased.[5] A Roman family's continued commitment to care of its dead was a measure of its integrity, and sense of responsibility to its community.

Funeral rites were the sole means of transition from death to the afterlife, and provided effective boundaries between the living and the dead. If properly honoured, cared for and remembered, the spirits of the dead could become ancestors and protectors of their living descendants.[6] If neglected, they were potentially hostile. Those who died without proper funeral rites could not enter the afterlife as benevolent ancestors, or as nameless di manes (gods of the underworld) but were thought to wander the earth, and haunt the living as vengeful ghosts (Lemures), to be placated annually at the Lemuria festival. In Horace's Ode 1.28, the shade of a drowned sailor, trapped through no fault of his own between the worlds of the living and the dead, implores a passer-by to "sprinkle dust three times" on his corpse and give him rest, or suffer his revenge. Cicero (Laws 2.22.57) writes that "... until turf is cast upon the bones, the place where the body is cremated does not have a sacred character...." The casting of earth or placing of turf on the cremated bones might have been the minimum requirement to make a grave a locus religiosus (a religious place, therefore protected by the gods). Burial rites, and burial itself, could be denied to certain categories of criminal after execution, a demonstration that the power of the state could extend to the perpetual condemnation of souls.[7]

Obligations of the familia

Rome's laws of inheritance determined who paid for, arranged and led funerals; usually the paterfamilias as main beneficiary, but if he was also the deceased, then his heir must take responsibility. Failing that, someone could be nominated to the task of leading the ceremonies, but the cost still fell to the heir or heirs; or as Cicero put it, the responsibility went with the money. If the deceased was a married woman, the cost should be paid by her husband, or from her dowry if she had been emancipated from her father.[8] A slave who died as a loyal member of a familia might receive a decent funeral, housing in the familia mausoleum, tomb or columbaria (shared "dovecote" style mausoleum) and commemoration in an inscription;[9] A freedman or woman might be buried and commemorated at the expense of their patron.[10] All others could apply to join officially recognised burial societies, which guaranteed a decent burial, or at least a memorial, as long as due subscriptions were kept up-to-date [11][12][13] Some persons and professions, such as gladiators, butchers and executioners were permanently polluted and dishonoured by their professional association with blood and death, and belonged to a social category known as infames, allowed a very restricted set of citizens' rights. They had their own burial clubs and segregated cemeteries, with funerals and memorials for their members.[14]

Families were under no customary or religious duty to give funeral or burial rites to infants, and were dissuaded from offering them cremation rites or cemetery burial unless the infant had cut its first teeth. Until it had been named by its father on its dies lustricus (name-day), 8 or 9 days after birth, an infant or new-born who died remained ritually pure; its death polluted no-one, and its spirit could not become a malevolent, earthbound shade.[15] It therefore needed no funeral rites, and could be buried within the pomerium if under 4 days old. Plutarch held that until a child no longer fed through its umbilical cord, it was "more like a plant than an animal", and that while sadness at its lost potential was entirely natural, mourning should be restrained.[16] The death rate among newborns and young children was very high – around 1 in 4 births, or at worst, up to 50% mortality before age 5; dietary deficiencies hindered growth and immunity among the poor, whether slave or free. Unwanted newborns were sometimes deliberately killed if patently "unfit to live". Others, perhaps of doubtful paternity or born, unwanted, to impoverished or enslaved parents, might be exposed "for the gods to take care of".[17][18] Nevertheless, some infants who died during or soon after birth were lovingly commemorated; in at least one such burial, the infant was accompanied to their afterlife with a coin to pay the ferryman. Grave goods in infant burials could include toys, pets, food and images of protective childhood or birth deities, to guard the child's soul on its journey.[19][20]

Responsibility of the State

The state intervened in several public and private aspects of burial and funeral practice; sumptuary laws were used to restrain expenditure and conspicuous display of wealth, privilege and excess at funeral feasts. "Excessive" mourning was officially frowned on, as was the use of dressed timbers (timbers "finished with the axe") for the funeral pyre. Cicero describes the provision of a funeral and rites as a "natural duty", consistent with universal notions of human care and decency.[21] Some individuals might nevertheless attempt to lawfully escape the burden and expense of a funeral obligation, through the courts, or unlawfully avoid even the most basic disposal costs for a relative or slave, and simply dump the body. Bodel (2000) calculates that around 1500 abandoned and unwanted corpses, not counting victims of epidemics, had to be removed from the streets of Rome every year.[22]

Undertakers

Undertakers supplied a broad range of services, considered demeaning or ritually unclean to most citizens.[23] Fragments of an undertaker's monopoly contract (c. 100 – 50 BC) with the town of Puteoli show that the undertaker also doubled as the town executioner. He and his 32 permanent staff lived outside the municipal boundary, and could only enter the town to carry out their trades; the public were charged for this at a given rate-per-mile, plus hire or purchase of necessary equipment and services. Funerals of decurions took precedence, followed by funerals of the young. Certain services had to be provided without additional payment, in a timely manner, and in a specific order of priority. For example, any slave's corpse left on the street must be removed "within two hours of daylight", without mourning or funeral rites, and the slave's owner must pay a 60 sestertii fine to the municipality. The corpses of suicides by hanging, being particularly offensive to the gods, must be removed within the hour of discovery, again without mourning or funeral rites. Not every city had such professionals on its public payroll; but many did, and it is assumed that the arrangements in Puteoli broadly reflected those in Rome.[24][25] The profession of undertaker was simultaneously "purifying and inherently sordid"; a necessary and ignoble trade, whose practitioners profited from blood and death. For contractors, it was almost certainly very profitable.[26]

A likely headquarters for the City of Rome's primary official undertaker (or several such, given the size of the city, and its growth) is the Esquiline Hill. Up to the end of the Republic an area just outside the Esquiline Gate was used as a dump for the bodies of executed criminals and crucified slaves, the former often condemned to suffer a final indignity of being "dragged with the hook" for disposal by birds and beasts, and the latter usually being left to rot on their crosses. A temple in Libitina's grove on the Esquiline was dedicated to Venus Libitina as a patron goddess of funerals and undertakers, "hardly later than 300 BC."[27] Libitina herself appears to have had no independent cult, shrine or worshipers; her name is the likely source for the usual title of undertakers Libitinarii, but it also appears to have been euphemistic for virtually all that pertained to undertakers and funerals, including biers ("couches of Libitina") and death itself. The area was notoriously mephitic and malodorous, but was covered over with soil and turned into a public garden during the reign of Augustus; at more or less the same time, cremations were banned to a distance of 2 miles from the walls. Cicero thought this had to do with minimising the risk of fires. Various structures built from around this time, including extramural tumulus-like mausolea, and very large columbaria with built-in mass-crematoria, have been suggested as attempts to serve the burial needs of the very poor. [28] A fee payable for death registration at the offices of the Esquilline undertakers - a sort of "death tax" - was used to fund the states' contribution to several festivals, including the Parentalia and sacred games such as the Ludi Apollinares and Ludi Plebeii.[29]

Announcing a death

The more-or-less immediate removal and disposal recommended for slave corpses is in signal contrast to elite funerals, wherein the body of the deceased could remain in their family home for several days after death, while their funeral was arranged. If the deceased was socially prominent, the death was announced by a herald, in the forum or other part of the city centre. Doors were closed, as a sign of mourning, and cypress branches arranged at the entrance to the house; a warning to all, especially the pontifices, that from this time until the end of the funeral, those who entered risked pollution.[30] The family ceased their daily routines for the duration of the full mourning period. They should not wash or otherwise care for their own person and could not offer sacrifice to any deity.[31]

Preparation of the body

When a person died at home, family members and intimate friends gathered around the death bed. In accordance with a belief that equated the soul with the breath, the closest relative sealed the passing of spirit from the body with a last kiss, and closed the eyes. The relatives began lamentations, the women scratching their faces until they bled,[32] and calling on the deceased by name throughout the funeral ceremony. The family was assisted by an undertaker and his staff, who were allowed to touch and handle the corpse, being permanently ritually unclean by virtue of their profession (see Infamia). The male relatives did not touch the body; it was placed on the ground, washed and anointed by female relatives, then placed on a funerary bier. The placing of the body on the ground is a doublet of birth ritual, when the infant was placed on the bare earth.[33]

Mourners were expected to wear the dress appropriate to the occasion, and to their station; an elite male citizen might wear a toga pulla (a "dark" toga, reserved for funerals).[34][35] If the deceased was a male citizen, he was dressed in his toga; if he had attained a magistracy, he wore the toga appropriate to that rank; and if he had earned a wreath in life, he wore one in death.[36] Wreaths also are found in burials of initiates into mystery religions.[37] After the body was prepared, it lay in state in the atrium of the family home (domus), with the feet pointed toward the door, for up to seven days.[38] Other circumstances pertained to those who lived, as most urban Romans did, in apartment buildings (insulae) or to the rural settings where the vast majority of Romans lived and died; but little is known of them. Elite practices are better documented, though likely often retrospective, idealised, speculative and antiquarian, or poetic. Cicero writes that for most commoners, the time between death and disposal was about 24 hours. This would have allowed virtually no time for lying in or other long-drawn ceremony.[39]

Although embalming was unusual and regarded as mainly an Egyptian practice, it is mentioned in Latin literature, with several instances documented by archaeology in Rome and throughout the Empire, as far afield as Gaul. Toynbee speculates that a number of these could have been the work of Egyptian priests of Isis and Serapis, in service of clients, converts or just people who liked the idea of this form of preservation.[40] Since elite funerals required complex and time-consuming arrangements, the body had to be preserved in the meantime, whether it was destined for burial or cremation.[41] The emperor Nero promoted his dead wife Poppaea as a goddess of the Roman state, with divine honours at state expense but broke with imperial tradition and convention by having her embalmed and entombed after the Egyptian manner, rather than cremated.[42]

Charon's obol

"Charon's obol" was a coin placed in or on the mouth of the deceased.[43] The custom is recorded in literary sources and attested by archaeology, and sometimes occurs in contexts that suggest it may have been imported to Rome as were the mystery religions that promised initiates salvation or special passage in the afterlife. The custom was explained by the myth of Charon, the ferryman who conveyed the souls of the newly dead across the water — a lake, river, or swamp — that separated the world of the living from the underworld. The coin was rationalized as his payment; the satirist Lucian remarks that in order to avoid death, one should simply not pay the fee. In Apuleius's tale of "Cupid and Psyche" in his Metamorphoses, framed by Lucius's quest for salvation ending with initiation into the mysteries of Isis, Psyche ("Soul") carries two coins in her journey to the underworld, the second to enable her return or symbolic rebirth. Evidence of "Charon's obol" appears throughout the Western Roman Empire well into the Christian era, but at no time and place was it practiced consistently and by all.

Funeral procession

The funeral procession (pompa funebris) assembled and made its way

A professional guild (collegium) of musicians specialized in funeral music.[44] Horace mentions the tuba and the cornu, two bronze trumpet-like instruments, at funerals.[45]

Eulogy

The eulogy (laudatio funebris) was a formal oration or panegyric in praise of the dead. It was one of two forms of discourse at a Roman funeral, the other being the chant (nenia).[46] The practice is associated with noble families, and the conventions for words spoken at an ordinary person's funeral go unrecorded. While oratory was practiced in Rome only by men, an elite woman might also be honored with a eulogy.

For socially prominent individuals, the funeral procession stopped at the forum for the public delivery of the eulogy from the Rostra.[47] Thus a well-delivered funeral oration could be a way for a young politician to publicize himself.[48] Aunt Julia's Eulogy (Laudatio Juliae Amitae), a speech made by the young Julius Caesar in honor of his aunt, the widow of Gaius Marius, helped launch his political career as a populist.[49]

The epitaph of the deceased in effect was a digest of the eulogy made visible and permanent,[50] and might include the career (cursus honorum) of a man who had held public offices. In commemorating past deeds, the eulogy was a precursor to Roman historiography.

Disposal

The place of burial was usually located outside the city boundary to avoid the pollution of the living.[51] Some prominent statesmen and their families might even have long-established family tombs within the ritual boundary (pomerium) of the city; a rare privilege.[24]

Sacrifices

Once the funeral procession had arrived at the place of burial or cremation, a portable altar was set up and sacrifice was made in the presence of the deceased. This usually meant the offer of a sow to Ceres, Rome's principal grain, harvest and field goddess. She was a doorwarden between the realms of the upperworld and the underworld, the living and the dead; the shade of the deceased could not pass into the underworld or afterlife without her consent. The victim was consecrated by sprinkling with mola salsa, a sacred mixture of salt and grain or flour, then stunned or killed with an axe or hammer, turned on its back and gutted. The guts (exta) were placed in an earthenware pot.[52]

The exta were the divine portion, preferred by the gods. Ritual errors were presumed to cause divine dissatisfaction, expressed by the poor condition of the exta, especially the liver, in which case the sacrifice or the rites must be repeated correctly. If all seemed satisfactory, the sacrificial victim was cut up, and distributed. A small portion of flesh for the deceased was cremated on a spit with the body or, if a burial, placed alongside it. The exta were placed in an earthenware pot and burned on the portable altar. The deceased had now transitioned to the underworld. They could no longer share meals with the living, nor with their former domestic gods (the Lares and Penates), only with what was appropriate for the collective spirits of the dead, the Manes.[53] The living used "fire and water" to cleanse themselves of the pollution incurred by their contact with the dead, and left the deceased in their new "home" (the tomb).

As far as Cicero was concerned, a burial was not religious and a grave was not a grave unless a sow had been sacrificed.[54] But a still higher status funeral might sacrifice a more costly domestic animal, such as an ox, or several victims of different kinds; and while animal sacrifice was preferred, those who could not afford it could offer a libation of wine, and grain or other foodstuffs, less potent than animal sacrifice but Ovid says that Ceres is content with little, as long as the offering is pure [55]

Grave goods

Like their Etruscan neighbours, the Romans held a deepseated notion that the individual soul survived death, and went to great lengths to help the dead feel comfortable, and "at home" in the tomb. Several quite different beliefs and customs seem to have been held. Many epitaphs and sculptural representations suggest that the deceased rested "in the bosom of a kindly Mother Earth". While individual souls were thought to merge into an undifferentiated collective of underworld deities (dii inferii) known as Manes gods, the provision of grave goods implies that at least some personal qualities, appetites and preferences were believed to survive along with the soul, and resided in or with the body or ashes in the grave. Grave goods could include fine quality clothing, personal ornaments, perfumes, food and drink, and blood, which the deceased presumably needed, or enjoyed. Lamps were ubiquitous.[56] In some burials, grave goods appear to have been ritualistically "killed", being deliberately damaged before burial. In others, damaged goods may have been used as a matter of economy. Some graves contain one or more large nails, possibly to help "fix" the shade of the dead in the grave, and prevent their haunting of the living.[57]

In Roman Britain, many burial and cremation sites of infants who had teethed and died contained small jet bear carvings, lunulae and phallic symbols, beads, bells, coins, and pottery beakers.[58] In the Graeco-Roman world, the bear was an animal of Artemis, whose roles included the protection of childbirth, nursing, and infant girls.[59] In Brescia, Italy, bear figurines appear to have functioned as guides and companions for in the afterlife. The lunula, and the phallus with a horn invoked protection from evil and misfortune. Beads found in burial sites were made out of various materials and often used for medicinal purposes in the realm of the living. Pliny claims in his Historia Naturalis that jet can cure toothaches and other ailments.[60] Bells, epecially tintinabulli helped to drive away evil and avert the evil eye.[61] Bells were also set into the mortar of the Roman Catacombs as a protective device over children's tombs. This was especially common in the fourth century.[62]

Inhumation, cremation and os resectum

Although inhumation was practiced regularly in archaic Rome, cremation was the most common burial practice in the Mid- to Late Republic and the Empire into the 1st and 2nd centuries. During that time, crematory images appear in Latin poetry on the theme of the dead and mourning. In one of the best-known classical Latin poems of mourning, Catullus writes of his long journey to attend to the funeral rites of his brother, who died abroad, and expresses his grief at addressing only silent ash.[63] When Propertius describes his dead lover Cynthia visiting him in a dream, the revenant's dress is scorched down the side and the fire of the pyre has corroded the familiar ring she wears.[64]

Patrician members of the gens Cornelia seem to have resisted this change and continued inhumating their dead until the first century BC. In 79 BC, the dictator Sulla was the first patrician Cornelius to be cremated, perhaps because he feared his body would be defaced by his former enemies.[65] Toynbee describes the change from burial to cremation as generally starting, excepting a few noble families, by 400 BC. Bodel (2008) places the main transition as the 1st to 2nd century AD.[66]

In the late 1st century AD, cremation was such a commonplace that Tacitus could refer to it as Romanus mos ("the Roman Way").[67] According to Plutarch, king Numa Pompilius had forbidden cremation; so perhaps in at least partial obedience to this prohibition, and perhaps on the understanding that "a part implies the whole", a complete finger was sometimes cut from the corpse before cremation and buried separately, unburnt, to complete the household's purification, return the deceased to mother Earth and make the grave inviolable. The practice, known as os resectum ("cut-off bone") is attested by literary sources (Cicero, de legibus, 2.55; Varro, lingua Latina, 5.23; Pauly Festus 135 L.[7][68][69]

Over time, starting around the reign of Hadrian, inhumation once again became the norm. Eventually, cremation remained a feature of imperial deification funerals, and very few others. The reasons for this shift are not well understood. Some evidence points to Christianity, mystery religions, or influence by the wealthier class in the Roman empire. In terms of sheer practicality, digging and then filling a hole in the ground required far less skilled manpower than did the construction of a pyre, and incurred little expense other than hire or rent of cemetery space.[70]

Individual cremations would have been more costly and time-consuming than inhumations, or mass cremations. Wood for fires was expensive; a well built funeral pyre took time and skill to construct, and consumed a great deal of dry timber. The pyre was built in a shallow pit. Once alight, the pyre must be tended for many hours to ensure that the body was completely consumed; the unplanned cremations of Pompey and Caligula proved to be signal failures, as their bodies remained part-burnt for want of sufficient fuel or skill.

Once the body had been consumed by the fire, the ashes would be sprinkled with wine, placed in an urn and buried either in or next to that spot (in which case the funeral place was a bustum) or taken elsewhere, in which case the cremation place was known as ustrina.[71] The smoke of the burning could be sweetened with aromatic herbs, leaves and libations; the elite could use incense.[72][73] The family had a private meal (silicernium) at the graveside, then returned home.[74]

Novendialis

On the ninth day after the person died, the funeral feast and rites called the novendialis or novemdialis were held.[75] Another sacrifice was often made, to the Manes of the deceased (or possibly, the family Penates), and the entire body of the victim was burned on the ground, not shared with the living. A libation to the Manes was poured onto the grave.[76] This concluded the period of full mourning.[77] Mourning dress was put aside, open house was declared and a feast was given.[78]

Commemorations

The care and cultivation of the dead did not end with the funeral and formal period of mourning, but was a perpetual obligation. Cicero stated that the main and overriding function of the priesthood with respect to the dead accorded with universal, natural law: to keep alive the memory of the deceased, by holding the traditional rites.[79] Libations were brought to the grave, and some tombs were even equipped with "feeding tubes" to facilitate delivery.

Funeral games (ludi funebres)

Roman and Greek literature offers dramatic accounts of games to honour or propitiate the spirits of the dead.[80] Very similar episodes are depicted on the walls of elite tombs in Etruria, and Campania; some appear to show combats to the death. The first such ludi funebres in Rome were given in 264 BC, during the war against Carthage; three pairs of gladiators fought to the death at the pyre of Brutus Pera, in what was described as a munus (pl. munera), a duty owed to an ancestor by his descendants – in this case, his son, Decimus Junius Brutus Scaeva. A feast was provided for friends and family. Thereafter, similar gladiatora munera became a core event at elite Roman funeral games. In the late Republic, a munus held for the funeral of the ex-consul and Pontifex Maximus Publius Licinius in 183 BC involved 120 gladiators fighting over 3 days, public distribution of meat (visceratio data) and the crowding of the forum with dining couches and tents as venue for the feast.[81]

Attitudes to gladiator munera varied; they were very popular, and thus politically useful. But they were also thought luxurious, self-indulgent and contrary to Roman morality – Publius Sempronius Sophus divorced his wife because she had attended a munus without his knowledge.[82] Sulla showed his usual political acumen during his stint as praetor, when he broke his own sumptuary laws to honour his dead wife, Metella, with an exceptionally lavish gladiator munus.[83] The host (editor) of a munus stood to gain votes in his political career, for even a promise of funeral games. The gladiators themselves could be admired for their courage, and despised for the bloodiness of their profession, which sometimes approximated that of excecutioner. The insulting term bustuarius ("tomb-man") was sometimes used for the lower class of gladiator, who might thus be perceived as provider of fodder for the spirits of the dead.[84] Julius Caesar broke any strict link between funerals and munera when he dedicated his ludi of 65 BC, with its 320 pairs of gladiators, to his father, who had been dead for 20 years.[85]

In the Imperial era, the state took over the organisation and subsidy of the most lavish munera, incorporating them into the existing, long-standing roster of public, state-sponsored events (ludi).[86] Any originally religious elements in munera tended to be subsumed by their entertainment value. In the mid-to-late Empire, Christian spectators who commented on the gladiator games thought them a particularly savage and perverse form of human sacrifice.

Festivals and cults of the dead

In February, the last month of the original Roman calendar when March 1 was New Year's Day, the dead were honored at a nine-day festival called the Parentalia, followed by the Feralia on February 21, when the potentially malign spirits of the dead were propitiated. During the Parentalia, families gathered at cemeteries to offer meals to the ancestors, and then shared wine and cakes among themselves (compare veneration of the dead in other cultures). Other events, such as the Rosalia (festival of Roses), the Violaria (a festival of Attis) but especially the dies natalis (birthday) of the deceased featured tombside dining. The Parentalia, being an official festival, would have entailed a simultaneous mass movement of families, making their various ways to the extramural cemeteries where their deceased had been laid to rest; just as importantly, they could be seen doing so by other families; behaviour at these festivals followed a fine line between ostentatious self-display and unaffected (sometimes drunken) joie de vivre. "House tombs" for wealthy, prominent though perhaps not elite families were constructed with a low-walled exterior precinct and a decorated room for banqueting, complete with shelving, cooking facilities and stone-built banqueting couches or with space for couches to be brought in. The participants in the tombside banquets could see their neighbours, and in turn, be seen; guests could be invited to the proceedings.[87]

A slab mounted near the tomb's entrance listed its past and present incumbents, and who was entitled to be imurred there in the future. This monumental function was of particular relevance to freedmen, who might not currently qualify for citizenship but could expect their children to do so at some time in the future. They had no lineage or familia of their own (or none recognised in law); but took on the name of the owner who had freed them. With each family death, a burial, name and epitaph would be added to those already on the tomb frontage, thus providing the beginnings of a personal and family history to be read by any passer-by, transforming the deceased from "polluted body to sanctified ancestor". Each tombside banquet reiterated and reinforced the message. Most tomb owners commissioned extravagant architectural and decorative features to solicit attention and admiration, and made provision in their wills for the cost of family banquets and festivals. Families had space within and outside to dine comfortably together, perhaps with the deceased as host, and be seen doing so by their friends, alies and rivals.[88]

Epitaphs

Epitaphs are one of the major classes of inscriptions. An epitaph usually noted the person's day of birth and lifespan.[51] Information varies, but collectively they offer information on family relationships, political offices,[89] and Roman values, in choosing what aspects of the deceased's life to praise. In a funeral culture that sought to perpetuate remembrance of the dead beyond the power of individual memory, epitaphs and markers counted for a lot.

Philosophical beliefs may also be in evidence. The epitaphs of Epicureans often expressed some form of the sentiment non fui, fui, non sum, non desidero, "I did not exist, I have existed, I do not exist, I feel no desire,"[90] or non fui, non sum, non curo, "I did not exist, I do not exist, I'm not concerned about it."[91]

For those families who could not afford a durable inscription, the passage of time would have brought considerable anxiety, as such grave markers as they could provide gradually eroded, shifted or were displaced, with the grave's exact location, and the identity of the deceased, lost as the cemetery gradually filled.[92] Most Roman slaves were servi rustici, used for agricultural labour, with few (if any) opportunities to buy their freedom with money or the promise of future favours. Almost all would have been enslaved for the whole of their lives, "and it is thought that they practically never appear in the epigraphic (or any other) record."[93]

Funerary art

Imagines ("images")

Noble Roman families often displayed a series of "images" (sing. imago, pl. imagines) in the atrium of their family home. [97] There is some uncertainty about whether these "images" were funeral masks, busts, or both together. The "images" could be arranged in a family tree, with a title (titulus) summarizing the individual's offices held (honores) and accomplishments (res gestae),[98] a practice that might be facilitated by hanging masks.[99] In any case, portrait busts of family members in stone or bronze were displayed in the home as well.[100]

Funeral masks were most likely made of wax and possibly molded as death masks directly from the deceased. They were worn in the funeral procession either by actors who were professional mourners, or by appropriate members of the family. Practice may have varied by period or by family, since sources give no consistent account.[101]

The display of ancestral images in aristocratic houses of the Republic and the public funerals are described by Pliny, Natural History 35, 4–11.[102]

Since references to "images" often fail to distinguish between commemorative portrait busts, extant examples of which are abundant, or funeral masks made of more perishable materials, none can be identified with certainty as having survived. The veristic tradition of funerary likenesses, however, contributed to the development of realistic Roman portraiture. In Roman Egypt, the Fayum mummy portraits reflect traditions of Egyptian and Roman funerary portraiture and the techniques of Hellenistic painting.

Graves, tombs, and cemeteries

Urban and suburban

In Rome, burial places were "always limited and frequently contested."[103] Legislation forbidding almost all burials within the ritual boundaries of cities led to the development of necropolises alongside extramural roads, veritable "cities of the dead", with their own main and access roads, water supplies and prime development sites where the rich could erect grand monuments or mausolea. Amenities for visitors included rooms for family dining, kitchens and kitchen gardens. Plots could be rented or bought, with or without ready-made tombs, with those nearest the roadway generally offering the easiest access and greatest visibility. The great cemetery of Isola Sacra and the tombs that line both sides of the Via Appia Antica offer notable examples of roadside cemeteries[104]

Cemeteries, tombs and their dead were protected by religious and civil laws. Disturbance of a burial, through whatever means or reason, was thought to cause pain and discomfort to the dead.[105] A place used for burial was a locus religiosus; it belonged to the gods because a body had been buried there. Any place not belonging to the gods was profane, and could be used for any non-religious purpose; but the discovery of any previously unknown interment on profane (public or private) land created an immediate encumbrance to its further use; it now belonged to the gods as a logus religiosus, and could not be sold or otherwise disposed unless the pontifs agreed to revoke its status and remove the body or bones.[106] Most disputes over burials and graves were settled by the citizens involved, in civil courts, under advice from the pontiffs;[107] But Cicero records a major pontifical decision that graves in publicly owned land were not lawful, which paved the way for a mass exhumation just outside Rome's Colline Gate, and the land's eventual use as a public garden.

As cities and towns expanded beyond their original legal and ritual boundaries, formerly intramural cemeteries had to be redefined as "outside the city" with deeds and markers, or their burials moved, releasing much-needed land for public or private use. Some developers seem to have simply removed or ignored burial markers. Burial plots could be divided, subdivided and sold on, in parts or as a whole, or let out to help cover the cost; "guest burials" were sometimes explicitly forbidden, for fear that they set a precedent of habitual usage in claiming rights to the tomb.[108] Profits could be made from sacred land (containing graves or other loci religiosi), through donations or the sale of produce, such as flowers grown in a tomb's garden, but in theory (and in law) any resulting profit should be used only to improve that land or its facilities; for example, an improvement to the water supply for the walled gardens surrounding the tombs.[109]

Disturbance or damage to human remains, tombs and memorials carried substantial penalties – in some provinces it was a capital offence – but detection and punishment or compensation rather depended on whose remains, tombs, memorials were involved. Memorial stones have been found incorporated into houses, used to create monuments to completely unrelated persons, and reused in official buildings.In Puteoli, a fine of 20,000 sestercii was payable for damage to the tomb of a particular decurion (a local, junior magistrate).[110] Some burial places list the family names of those entitled to be placed there; some also list particular persons not entitled to be there, presumably in consequence of some family squabble or severance. There is also evidence of severe near-contemporary encroachments, theft of stones and unrepaired damage to tombs, grave markers and epitaphs. Tombs could be lawfully moved, after exemption by the pontifices, or decay along with the remains within.[111] In Pompeii, a legible memorial stone was discovered face-down, reshaped to make seating for a public latrine [112]

Rural villas and estates

A likely majority of Romans (Hopkins, 1981, calculates 80-90%) spent their entire lives in rural poverty, working on farms and villa estates as tenants, free labourers or slaves. Absentee landowners used the income from their farms to support town houses, military and political careers, and a lifestyle of cultured leisure. While some affected to despise money, farming was represented as an entirely appropriate, intrinsically noble occupation for retirement.[113] By the 2nd century BC, aristocratic villas with monumental tombs had become a part of the rural landscape, surrounded by the humbler tombs of commoner-tenants and bailiffs. Far from the main roads between towns and cities, the graves of free or enslaved field-workers dotted the fields, or occupied the middle areas of settlements on poor ground not worth the planting or grazing. In his capacity as a land surveyor, Siculus Flaccus found that the grave markers at the edge of estates were easily mistaken for boundary markers (cippi). Many of the elite chose retirement and burial among their ancestors at the farm and villa, from where they could keep a critical but benevolent eye on their descendants. The entire villa complex became a monument to the achievement of its founder; its heirs might not be permitted, under the terms of their inheritance, to sell the property as a whole, or piecemeal and were at least morally obliged to keep it in the family name. For this reason, some villas were passed to freedmen (who took the name of whoever had freed them). Whoever inherited or bought a property automatically acquired its graves, monuments and resident or household deities, including its dii Manes and Lares, who were closely associated - at least in popular opinion - with ancestor cult. In cases where the villa had to be sold, it was not unusual for the contract to include the former owner's rights of access, in order to continue their ancestral and commemorative rites.[114]

Common graves

Funerals were costly affairs, even where the rites could be tailored down to meet a low income. A ceremony that would have been recognised as acceptable to the Roman elite might represent several times the annual income of the average citizen, and an impossibility to the very poor, who might depend on an unpredictable day-wage, unable to afford or maintain a burial-club subscription. Some were doubtless unlawfully dumped by their relatives, or by the aediles or rather, by their assistants.[115]

Some modern scholars have assumed that the bodies of the poorest, whether slave or free, could be consigned to the same dishonourable places as executed criminals deemed obnoxious to the state (noxii), who are presumed to have been disposed of in pits (puticuli, s.puticulus) outside the town or city boundary, at best, or at worst dumped into sewers or rivers. For the truly impoverished, and during times of exceptionally high mortality such as famine or epidemic, mass-burials or mass-cremations with minimal or no rites might have been the only realistic option, and as much as the authorities and undertakers could cope with. It is extremely doubtful that any could have chosen such a fate.[115]

Basic pit graves

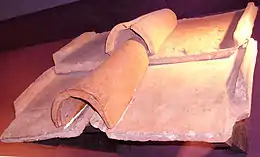

The least costly form of individual inhumation was the simple pit-grave, which could barely cover the remains, or enclose them with tile or stone slabs.[116] They were almost universal, in various forms, throughout the Republic and Empire, especially where there was little of no pressure for burial space. Orientation of the grave was generally east–west, with the head to the east.[117] Flanged tiles (or tegulae) were sometimes used to create a box-like "coffin". In some, a funnel or tube projected from the interior, and was used to offer libations during ceremonies honouring the dead. Grave goods were often deposited along with the body; a pillow of tufa or wood might be provided for the comfort of the deceased. Amphorae with crudely inscribed names or brief epitaphs were sometimes sunk into the centre of the grave, as markers and in some cases as feeding tubes. Roofed pit graves known as Alla cappuccina ("like a Capuchin monk's hood)" were common throughout Rome and its provinces, from the Roman Republic to Late Empire and beyond. Construction was cheap and versatile. The corpse was usually laid in a shallow pit, or directly on the ground, or within a wooden coffin. The whole was enclosed using large, flanged roof tiles, leaning together to form an apex or gable, protecting the body beneath.[116] This structure was then reinforced with either curved tiles (or imbrices), or stones and mortar. Pit graves were commonly used for single bodies; adults, children and infants, the last being inhumed, rather than cremated, even when the use of cremation was at its height.[118]

House tombs, Columbaria and mausoleums

The smallest "house tombs" were rectilinear, box-like structures with a plain roof and entrance. Some were just a little larger than the body within. Their structure afforded opportunities for decoration, including small wall-paintings, reliefs and mosaic walls and floors; extra floors could be added at need, above or below ground-level, to contain additional cremation urns, or inhumation burials. In some cases, mosaic floors within house tombs were carefully removed, an additional corpse interred, then the mosaic repaired and the whole resealed, with a "feeding tube" set into the mosaic to provide for the new interrment.[119] The larger "house tombs" had a broad doorway, but also a lobby and several large rooms within. One chamber was used to host the dead's family memorial ceremony and feast. Other chambers housed anything thought necessary for the deceased and their family, including family portraits and other valued possessions, along with any paraphernalia required for memorial ceremonies.[120]

Wealthy, prominent families built large, sometimes enormous, mausoleums. The Castel Sant'Angelo by the Vatican, originally the mausoleum of Hadrian, is the best preserved, as it was converted to a fortress.[121] The family Tomb of the Scipios was in an aristocratic cemetery, and in use from the 3rd century BC to the 1st century AD. A grand mausoleum might include bedrooms and kitchens for family visits, which would include feasts. Where space allowed, walled gardens were created around tombs, for family use during festivals. Some had small cottages built to house permanent gardeners and caretakers, employed to maintain the tomb complex, prevent thefts (especially of food and drink left there for the deceased) and evict any indigent homeless. Theft of food and possessions from tombs and graveyards denied the dead their due rights and support.[120] The bodies of the deceased were usually inhumed within sarcophagi, but some mausolea include cremation urns. Some late examples combine Christian and traditional "pagan" styles of burial.

The roads from cities were lined with smaller mausolea, such as the Tombs of Via Latina, along the Appian Way. The Tomb of Eurysaces the Baker is a famous and originally very ostentatious tomb in a prime spot just outside Rome's Porta Maggiore, erected for a rich freedman baker around 50–20 BC.[122] The tombs at Petra, in the far east of the Empire are cut into cliffs, some with elaborate facades in the "baroque" style of the Imperial period.

.jpg.webp)

Cheaper still were the Catacombs of Rome, famously used by Christians, but also by all religions, with some specialization, such as special Jewish sections. These were large systems of narrow tunnels in the soft rock below Rome, where niches were sold to the families of the deceased in a very profitable, if rather smelly, trade. Decoration included paintings, many of which have survived.[123]

In the Christian period, burial near the grave of a famous martyr became desirable, and large funeral halls were opened over such graves, which were often in a catacomb underneath. These contained rows of tombs, but also space for meals for the family, now probably to be seen as agape feasts. Many of the large Roman churches began as funeral halls, which were originally private enterprises; the family of Constantine owned the one over the grave of Saint Agnes of Rome, whose ruins are next to Santa Costanza, originally a Constantinian family mausoleum forming an apse to the hall.[124][125]

Sarcophagi

The funerary urns in which the ashes of the cremated were placed were gradually overtaken in popularity by the sarcophagus as inhumation became more common. Particularly in the 2nd–4th centuries, these were often decorated with reliefs that became an important vehicle for Late Roman sculpture. The scenes depicted were drawn from mythology, religious beliefs pertaining to the mysteries, allegories, history, or scenes of hunting or feasting. Many sarcophagi depict Nereids, fantastical sea creatures, and other marine imagery that may allude to the location of the Isles of the Blessed across the sea, with a portrait of the deceased on a seashell.[126] The sarcophagus of a child may show tender representations of family life, Cupids, or children playing.

Some sarcophagi may have been ordered during the person's life and custom-made to express their beliefs or aesthetics. Most were mass-produced, and if they contained a portrait of the deceased, as many did, with the face of the figure left unfinished until purchase.[128] The carved sarcophagus survived the transition to Christianity, and became the first common location for Christian sculpture, in works like the mid-4th-century Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus.[129]

Military funerals and burial

"The cult of the dead," it has been noted,[130] "was particularly important to men whose profession exposed them to a premature demise." The Roman value of pietas encompassed the desire of soldiers to honor their fallen comrades, though the conditions of war might interfere with the timely performance of traditional rites.[131] Soldiers killed in battle on foreign soil with ongoing hostilities were probably given a mass cremation or burial.[132] Under less urgent circumstances, they might be cremated individually, and their ashes placed in a vessel for transport to a permanent burial site.[133] When the Roman army under the command of Publius Quinctilius Varus suffered their disastrous defeat at the Battle of Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD, they remained uncommemorated until Germanicus and his troops located the battlefield a few years later and made a funeral mound for their remains.[134]

In the permanent garrisons of the Empire, a portion of each soldier's pay was set aside and pooled for funeral expenses, including the ritual meal, the burial, and commemoration.[135] Soldiers who died of illness or an accident during the normal routines of life would have been given the same rites as in civilian life.[136] The first burial clubs for soldiers were formed under Augustus; burial societies had existed for civilians long before. Veterans might pay into a fund upon leaving the service, insuring a decent burial by membership in an association for that purpose.[137]

Tombstones and monuments throughout the Empire document military personnel and units stationed at particular camps (castra). If the body could not be recovered, the death could be commemorated with a cenotaph.[131] Epitaphs on Roman military tombstones usually give the soldier's name, his birthplace, rank and unit, age and years of service, and sometimes other information such as the names of his heirs. Some more elaborate monuments depict the deceased, either in his parade regalia[139] or in civilian dress to emphasize his citizenship.[140] Cavalrymen are often shown riding over the body of a downtrodden foe, an image interpreted as a symbolic victory over death.[141] Military funeral monuments from Roman Africa take progressively more substantial forms: steles in the 1st century, altars in the 2nd, and cupulas (mounds) in the 3rd. Tombs were often grouped in military cemeteries along the roads that led out of the camp. A centurion might be well-off enough to have a mausoleum built.[142]

If a commander was killed in action, the men rode or marched around his pyre, or in some circumstances a cenotaph.[132]

Afterlife

Religion

Standard accounts of Roman mythology describe the soul as immortal[143] and judged at death before a tribunal in the underworld,[144] with those who had done good being sent to the Elysian Fields and those who had done ill sent to Tartarus.[145] It is unclear how ancient such beliefs were, as they seem influenced by Greek mythology and mystery cults.

The mysteries continued under Rome and seem to have promised immortality only for the initiated. Known forms of esoteric religion combined Roman, Egyptian, and Middle Eastern mythology and astrology, describing the progress of its initiates through the regions of the moon, sun, and stars. The uninitiated or virtueless were then left behind, the underworld becoming solely a place of torment. Common depictions of the afterlife of the bless include rest, a celestial banquet, and the vision of God (Deus or Jupiter).[145]

Philosophy

The mainstream of Roman philosophy, such as the Stoics, advocated contemplation and acceptance of the inevitability of death of all mortals. "It is necessary for some to stay and for others to go, all the while rejoicing with those who are with us, yet not grieving for those departing."[146] To grieve bitterly is to fail to perceive and accept the nature of things. Famously, Epictetus encouraged contemplation of one's loved ones as a "jar" or "crystal cup" which might break and be remembered without troubling the spirit, since "you love a mortal, something not your own. It has been given to you for the present, not inseparably nor forever, but like a fig... at a fixed season of the year. If you yearn for it in the winter, you are a fool."[147] There was no real consensus, at least among surviving Roman texts and epitaphs, of what happened to a person after death or the existence of an afterlife. Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia claims that most people are of the opinion that after death one returns to the non-sensing state that occurred before birth but admits, however scornfully, that there are people who believe in the immortality of the soul.[148] Seneca the Younger seems to be less consistent, arguing both sides, indicating that death brings about utter annihilation while also talking about some survival of the spirit after it escapes from the prison of the body.[149] Tacitus at the end of Agricola takes the opposite opinion to Pliny, and claims that the wise believe the spirit does not die with the body, although he may be specifically referring to the pious [150] – which harkens to the mythological idea of Elysium.

See also

- Rosalia, a festival of rose-adornment reflecting the practice decorating tombs and cemeteries with flowers

- Ancient Greek funeral and burial practices

- Roman funerary art

- Sit tibi terra levis

References

- Literally, the "way of the greater ones" but understood as "the way of the ancestors".

- Michele Renee Salzman, "Religious koine and Religious Dissent," in A Companion to Roman Religion (Blackwell, 2007), p. 116.

- Stefan Heid, "The Romanness of Roman Christianity," in A Companion to Roman Religion, p. 408.

- Average life expectancy (for all) ranged from approximately 20 to 30. Bodel provides a conservatively estimated average of 80 deaths daily in the city of Rome (or 30,000 per annum), not counting deaths from epidemics, plagues and executions; see Bodel, John, "Dealing with the Dead: Undertakers, Executions And Potters' Fields", in: Death and Disease in the Ancient City, eds: Hope, Valerie M., and Marshall, Eirean, Routledge Classical Monographs, 2000, pp. 128–130.

- Bodel, John, "The Organization of the Funerary Trade at Puteoli and Cumae," in S. Panciera, ed. Libitina e dintorni (Libitina 3) Rome, 2004 pp. 149–150.

- Erker, Darja Šterbenc, "Gender and Roman funeral ritual", pp. 41–42

- Graham, Emma-Jayne in Maureen, and Rempel, Jane, (Editors), "Living through the dead", Burial and commemoration in the Classical world, Oxbow Books, 2014, pp. 94–95.

- Toynbee, 1996, p.54

- Hasegawa, K., The ‘Familia Urbana’ during the Early Empire, Oxford, 2005: BAR International Series 1440, cited in Graham, 2006, p.4 ff.

- Toynbee, 1996, pp. 54, 113–116.

- These were among the very few privately funded organisations encouraged by Rome's civil authorities, who otherwise tended to suspect any lower-class organisation of conspiracy against the status quo.

- Graham, E-J, The burial of the urban poor in Italy in the late Roman Republic and early Empire. BAR Int. Series 1565. Oxford, Archaeopress, 2006, pp. 4

- Maureen Carroll, Spirits of the dead: Roman funerary commemoration in Western Europe (Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 45–46.

- For some reason, from the late Republic onwards other infames, including undertakers, auctioneers and heralds, excluded from an active political life while they practised their profession, reverted to full citizenship if they abandoned it, and thereafter could stand for political office: see Bodel, John, "The Organization of the Funerary Trade at Puteoli and Cumae," in S. Panciera, ed. Libitina e dintorni (Libitina 3) Rome, 2004 pp. 149–150. Other professions suffering infamia, though for very different reasons, included actors and entertainers.

- Dasen, Veronique, "Childbirth and Infancy in Greek and Roman Antiquity", in: Rawson, Beryl, (editor), A Companion to Families in the Greek and Roman Worlds, Blackwell, 2011, pp. 292–307. The dies lustricus was held 9 days after birth for a boy, 8 for girls (Plutarch, Roman Questions, 288-B, and Macrobius, Saturnalia, 1, 16, 36.)

- Dasen, Childbirth and Infancy, 2011, pp. 307–308

- Harris, W, "Child-Exposure in the Roman Empire", in: Journal of Roman Studies, 84, (1994). Published by: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies, pp. 9, 12–14, 22, 93–95, 115.

- Pilkington, Nathan, "Growing Up Roman: Infant Mortality and Reproductive Development", in: The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, MIT, 44:1 (2013), pp. 5–21

- Toynbee, Death and Burial, pp. 53–54,

- This is discussed, with examples, in: Carroll, Maureen, "Infant Death and Burial in Roman Italy", Journal of Roman Archaeology 24, 2011 99–120

- Robinson, 1975, p. 176, citing Cicero, de legibus, 2.21.53–55.

- Bodel, John, "Dealing with the Dead: Undertakers, Executions And Potters' Fields", in: Death and Disease in the Ancient City, eds: Hope, Valerie M., and Marshall, Eirean, Routledge Classical Monographs, 2000, pp. 128–129.

- Besides their central, specialised roles in funerals, which included moving, dressing and applying cosmetics to the deceased, and organising the procession and burial, some could be privately hired to torture, flog or crucify slaves, to perform executions, and to carry or drag corpses from their pace of execution to a place of disposal.

- Erker, Darja Šterbenc, "Gender and Roman funeral ritual", pp. 41–42 in Hope, V., Huskinson, J,. (Editors), Memory and Mourning in Ancient Rome, Oxbow, 2011, pp. 40–60.

- Bodel, John, "The Organization of the Funerary Trade at Puteoli and Cumae," in S. Panciera, ed. Libitina e dintorni (Libitina 3) Rome, 2004 pp. 149–70, especially p. 166, note 43: Suicide by hanging was thought particularly abhorrent to the gods because it suspended a corpse "with rope and nail" above the ground; in this, it strongly resembled crucifixion, a humiliating form of capital punishment reserved for slaves and outlaws, and unlawful for citizens.

- Bodel, John, "Dealing with the Dead: Undertakers, Executions And Potters' Fields", in: Death and Disease in the Ancient City, eds: Hope, Valerie M., and Marshall, Eirean, Routledge Classical Monographs, 2000, pp. 135, 139–140.

- See Eden, P.T., "Venus and the Cabbage," Hermes, 91, (1963) p. 457. Varro rationalises the connections as "lubendo libido, libidinosus ac Venus Libentina et Libitina" (Lingua Latina, 6, 47).

- Bodel, John, "Dealing with the Dead: Undertakers, Executions And Potters' Fields", in: Death and Disease in the Ancient City, eds: Hope, Valerie M., and Marshall, Eirean, Routledge Classical Monographs, 2000, pp. 136, 144–145.

- Bodel, John, "Graveyards and Groves: a study of the Lex Lucerina", American Journal of Ancient History, 11 (1986) [1994]), Cambridge University Press, 2015, pp. 20-29

- Flower, Harriet, Ancestor Masks and Aristocratic Power in Roman Culture, Clarendon, Oxford University Press, reprint 2006, p. 92.

- Evidently this was a religious prohibition, not an ancient equivalent to modern notions of public health and disease prevention. See Erker, Darja Šterbenc, "Gender and Roman funeral ritual", pp. 41–42 in Hope, V., Huskinson, J,. (Editors), Memory and Mourning in Ancient Rome, Oxbow, 2011, pp. 40–60.

- This evidently happened often enough, and was sufficiently frowned upon by the elite, to be included in a list of forbidden funeral practises, based on a ban in the Laws of Twelve Tables and in Sumptuary Laws. Some, or most of the women mourners doing this might have been hired professionals. See Erker, Darja Šterbenc, "Gender and Roman funeral ritual", pp. 41–42

- Anthony Corbeill, Nature Embodied: Gesture in Ancient Rome (Princeton University Press, 2004), p. 90, with a table of other parallels between birth and death rituals on p. 91.

- A plain white toga was also acceptable; those with a toga praetexta could turn it inside out, to conceal its purple stripe; see Flower, Harriet F., Ancestor Masks and Aristocratic Power in Roman Culture, Oxford University Press, 1996, p. 102

- Heskel, J., in Sebesta, Judith Lynn, and Bonfante, Larissa (Editors) The World of Roman Costume: Wisconsin Studies in Classics, The University of Wisconsin Press, 1994, pp. 141–142, citing Cicero, In P. Vatinium testem oratio for the etiquette associated with the toga pulla.

- J.M.C. Toynbee, Death and Burial in the Roman World (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1971, 1996), pp. 43–44.

- Minucius Felix, Octavius 28.3–4; Mark J. Johnson, "Pagan-Christian Burial Practices of the Fourth Century: Shared Tombs?" Journal of Early Christian Studies 5 (1997), p. 45.

- Toynbee, Death and Burial, p. 44.

- Flower, Ancestor Masks, 2006, p. 93.

- Toynbee, Death and Burial, pp. 39, 41–42.

- Heller, L. John, Burial Customs of the Romans, (Washington: Classical Association of the Atlantic States, 1932), 194.

- Counts, Derek B. (1996). "Regum Externorum Consuetudine: The Nature and Function of Embalming in Rome". Classical Antiquity. 15 (2): 189–90, 196 (note 37, citing Pliny the elder, Natural History, 12.83). doi:10.2307/25011039. JSTOR 25011039.

- No ancient Greek or Latin source says that coins were placed on the eyes; the archaeological evidence points overwhelmingly to placement in or on the mouth, in or near the hand, or loosely in the grave. Coins that could be interpreted as placement on the eyes is relatively rare.

- Friederike Fless and Katja Moede, "Music and Dance: Forms of Representation in Pictorial and Written Sources," in A Companion to Roman Religion, p. 252.

- Horace Satire 1.6.45.

- Ann Suter, Lament: Studies in the Ancient Mediterranean and Beyond (Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 258.

- Geoffrey S. Sumi, "Power and Ritual: The Crowd at Clodius' Funeral," Historia 46.1 (1997), p. 96.

- Brendon Reay, "Agriculture, Writing, and Cato's Aristocratic Self-Fashioning," Classical Antiquity 24.2 (2005), p. 354.

- Gerard B. Lavery, "Cicero's Philarchia and Marius," Greece & Rome 18.2 (1971), p. 139.

- R.G. Lewis, Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt (1993), p. 658.

- Salzman, "Religious koine and Religious Dissent," p. 116.

- John Scheid, "Sacrifices to Gods and Ancestors," in A Companion to Roman Religion, pp. 264, 270.

- Scheid, "Sacrifices to Gods and Ancestors," pp. 264, 270–271.

- Cicero, De Legibus, 2. 22. 55–57.

- Linderski, J., in Wolfgang Haase, Hildegard Temporini (eds), Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt, Volume 16, Part 3, de Gruyter, 1986, p. 1947, citing Ovid, Fasti, 4.411–416.

- Toynbee, 1996, pp. 34–39

- Small, A., Small, C., Abdy, R., De Stefano, A., Giuliani, R., Henig, M., Johnson, K., Kenrick, P., Prowse, Small, A., and Vanderleest, H., "Excavation in the Roman Cemetery at Vagnari, in the Territory of Gravina in Puglia," 2002,Papers of the British School at Rome, Vol. 75 (2007), pp. 133–146

- CRUMMY, NINA (2010). "Bears and Coins: The Iconography of Protection in Late Roman Infant Burials". Britannia. 41: 37–93. ISSN 0068-113X.

- Price, T.H. 1978: Kourotrophos: Cults and Representations of the Greek Nursing Deities, Leiden.

- Pliny: Gaius Plinius Secundus, Historia Naturalis, Loeb Classical Library edition, vol. 3 trans. H. Rackham (1947), vols 7 and 8 by W.H.S. Jones (1956, 1963), vol. 10 by D.E. Eichholz (1971), Cambridge, Mass./London

- Ovid: Publius Ovidius Naso, Fasti, Loeb Classical Library edition, trans. J.G. Frazer, rev. G.P. Goold (1931), Cambridge, Mass.

- Nuzzo, D. 2000: 'Amulet and burial in late antiquity: some examples from Roman cemeteries', in J. Pearce, M. Millett and M. Struck (eds), Burial , Society and Context in the Roman World, Oxford, 249–255

- Catullus, Carmen 101, line 4 (mutam ... cinerem).

- Propertius 4.7.8–9.

- Henri Etcheto, Les Scipions. Famille et pouvoir à Rome à l’époque républicaine, Bordeaux, Ausonius Éditions, 2012, pp. 15, 16, 407 (note 4).

- Bodel, John, "From Columbaria to Catacombs: Collective Burial in Pagan and Christian Rome" in Brink, L., and Green, D., (Editors), Commemorating the Dead, Texts and Artefact in Context, de Gruyter, 2008, pp. 183–185.

- Toynbee, 1996, p. 40, citing Tacitus, Annals, 16.6

- Siebert, Anne Viola, "Os resectum", 2006 in: Brill’s New Pauly, Antiquity volumes edited by: Hubert Cancik and Helmuth Schneider, English Edition by: Christine F. Salazar, Classical Tradition volumes edited by: Manfred Landfester, English Edition by: Francis G. Gentry. Consulted online on 26 December 2020 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1574-9347_bnp_e901840>

- Roncoroni, Patricia, "Interpreting Deposits: Linking Ritual with Economy, Papers on Mediterranean Archaeology, ed: Nijboer, A., J., Caeculus IV, 2001, pp. 118–121.

- Darby Nock, Arthur (October 1932). "Cremation and Burial in the Roman Empire". The Harvard Theological Review. 25: 321–359 – via JSTOR.

- Noy, David. "Building a Roman Funeral Pyre". Antichthon. 34: 30–45. ISSN 0066-4774.

- Angelucci, Diego E. (1 September 2008). "Geoarchaeological insights from a Roman age incineration feature (ustrinum) at Enconsta de Sant'Ana (Lisbon, Portugal)". Journal of Archaeological Science. 35 (9): 2624–2633. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2008.04.020. ISSN 0305-4403.

- "LacusCurtius • The Roman Funeral (Smith's Dictionary, 1875)". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- Flower, Ancestor Masks, p. 94.

- Salzman, "Religious koine and Religious Dissent," p. 115.

- Scheid, John, "Sacrifices for Gods and Ancestors", in A Companion to Roman Religion, Wiley Blackwell, 2011, pp. 270–271.

- Toynbee, Death and Burial in the Roman World, p. 51.

- To wear mourning dress at the feast was considered an insult to the host, suggesting that he had somehow vitiated the funeral rites; see Heskel, J., in Sebesta, Judith Lynn, and Bonfante, Larissa (Editors) The World of Roman Costume: Wisconsin Studies in Classics, The University of Wisconsin Press, 1994, pp. 141–142

- Robinson, p. 177.

- In Homer's Iliad, Book 23, funeral games are held by Achilles to honour Patroclus. In Virgil's Aeneid, Book 5, Aeneas holds games on the anniversary of his father's death.

- Livy, 39.46.2.

- Plutarch, Roman Questions, 267 B, Valerius Maximus, 6.3–12.

- Kyle, Donald G. (2007), Sp ort and Spectacle in the Ancient World. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Publishing. p.285. ISBN 978-0-631-22970-4.

- Bagnani, Gilbert (January 1956). "Encolpius Gladiator Obscenus". Classical Philology. 51 (1): 24–27. doi:10.1086/363980.

- Wiedemann, Thomas (1992). Emperors and Gladiators. London, United Kingdom: Routledge. pp. 8–10. ISBN 0-415-12164-7.

- These included festival-based events at the Circus Maximus, such as chariot races, beast hunts and particular religious rites in the form of ludi scaenici – theatrical performances with a religious character, usually dedicated to a deity, particularly Jupiter, and the Roman people as a whole. See Bernstein, Frank, "Complex Rituals: Games and Processions in Republican Rome", in: Rüpke, Jörg, ed. A Companion to Roman Religion. Wiley Blackwell, 2011. pp. 222–232.

- Gee, Regina, "From Corpse to Ancestor: The Role of Tombside Dining in the Transformation of the Body in Ancient Rome", in: Fahlander, Fredrik, and Oestigaard, Oesti (editors), The Materiality of Death. Bodies, burials, beliefs, BAR International Series, 1768, Archaeopress, Oxford, 2008, pp. 59 ff, 62–65.

- Gee, Regina, From Corpse to Ancestor, pp. 59 ff, 61–63.

- Jack N. Lightstone, "Roman Diaspora Judaism," in A Companion to Roman Religion, p. 350.

- CIL 8.3463; Attilio Mastrocinque, "Creating One's Own Religion: Intellectual Choice," in A Companion to Roman Religion, p. 379.

- These became such standard sentiments that abbreviations came into inscriptional usage, for this last example NF NS NC.

- Graham, E-J, The burial of the urban poor in Italy in the late Roman Republic and early Empire. BAR Int. Series 1565. Oxford, Archaeopress, 2006, pp. 110–113.

- Bruun, Christer, "Slaves and freed slaves", in: Bruun, Christer and Edmondson, Johnathan, (Editors), The Oxford Handbook of Roman Epigraphy, Oxford University Press, 2014, p. 611

- Walker, Susan & al. The Image of Augustus, p. 9. British Museum Publications, 1981. ISBN 0714112704.

- Hopkins, Keith (27 June 1985). "Death and Renewal: Volume 2: Sociological Studies in Roman History". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 23 January 2017 – via Google Books.

- Fejfer, Jane (1 January 2008). "Roman Portraits in Context". Walter de Gruyter. Retrieved 23 January 2017 – via Google Books.

- A supposed ius imaginis ("right of the image") has sometimes been thought to restrict this privilege to the nobiles based on a single passage by Cicero, but scholars now are more likely to see the display of ancestral images as a social convention or product of affluence. See, for instance, Walker and Burnett.[94] and others.[95][96]

- R.G. Lewis, "Imperial Autobiography, Augustus to Hadrian," Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II.34.1 (1993), p. 658.

- Rabun Taylor, "Roman Oscilla: An Assessment," RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 48 (2005) 83–105.

- Lewis, "Imperial Autobiography," p. 658.

- Walker & Burnett, pp. 9–10

- Winkes, Rolf: Imago Clipeata, Studien zu einer römischen Bildnisform, Bonn 1969. Winkes, Rolf: Pliny's chapter on Roman funeral customs (American Journal of Archaeology 83, 1979, 481–484)

- Bodel, "From Columbaria to Catacombs" 2008, pp. 178–179

- Toynbee, Death and Burial, pp. 73-74, 93-95

- Toynbee, Death and Burial, pp. 75-76

- A death by lightning strike was thought a clear statement by Jupiter that the place and the victim belonged to him.

- Robinson, pp. 176–178.

- Toynbee, Death and Burial, pp. 76-78

- Robinson, pp. 176–179.

- Bodel, John, "The Organization of the Funerary Trade at Puteoli and Cumae," in S. Panciera, ed. Libitina e dintorni (Libitina 3) Rome, 2004 pp. 149–170.

- Lawful moving of graves was a not uncommon result of frequent flooding of cemeteries

- Robinson, Olivia, "The Roman Law on Burials and Burial Grounds", Irish Jurist, new series, Vol. 10, No. 1, (Summer 1975), pp. 175–186. Retrieved December 7, 2020, from Jstor

- The competitive acquisition of rural and suburban villas by the urban elite had been in process since the 6th century BC; the first known, named aristocratic owner of both a country villa (in this case, a coastal property) and suburban residence in Rome was Scipio Africanus. See Bodel, John, "Monumental Villas & Villa Monuments", Journal of Roman Archaeology, 10, 1997, pp. 1 - 7

- "The house is a tangible symbol of the man..." Demolition of a house could be employed as a form of Damnatio memoriae when this happened, the building plot was left empty, or its use was changed. The house was not replaced. See Bodel, John, "Monumental Villas & Villa Monuments", Journal of Roman Archaeology, 10, 1997, pp. 8, 20 - 24

- Graham, E-J, The burial of the urban poor in Italy in the late Roman Republic and early Empire. BAR Int. Series 1565. Oxford, Archaeopress, 2006, pp. 28–31.

- Nock, Arthur Darby (1932). "Cremation and Burial in the Roman Empire". The Harvard Theological Review. 25 (4): 321–359. ISSN 0017-8160.

- Small, A., Small, C., Abdy, R., De Stefano, A., Giuliani, R., Henig, M., Johnson, K., Kenrick, P., Prowse, Small, A., and Vanderleest, H., "Excavation in the Roman Cemetery at Vagnari, in the Territory of Gravina in Puglia," 2002, Papers of the British School at Rome, Vol. 75 (2007), pp. 134–135.

- Small, A., Small, C., Abdy, R., De Stefano, A., Giuliani, R., Henig, M., Johnson, K., Kenrick, P., Prowse, Small, A., and Vanderleest, H., "Excavation in the Roman Cemetery at Vagnari, in the Territory of Gravina in Puglia," 2002, Papers of the British School at Rome, Vol. 75 (2007), pp. 126, 132, 134–135

- Graham, E-J, The burial of the urban poor in Italy in the late Roman Republic and early Empire. BAR Int. Series 1565. Oxford, Archaeopress, 2006, pp. 87-88.

- Heller, L. John, Burial Customs of the Romans, (Washington: Classical Association of the Atlantic States, 1932), 197.

- Blagg, Thomas, in Henig, Martin (ed), A Handbook of Roman Art, pp. 64–65, Phaidon, 1983, ISBN 0714822140

- Strong, Roman Art, p. 125

- Strong, Roman Art, pp. 291–296

- Webb, Matilda. The churches and catacombs of early Christian Rome: a comprehensive guide, pp. 249–252.

- Blagg, Handbook, p. 65

- Donald Strong, Roman Art (Yale University Press, 1995, 3rd edition, originally published 1976), pp. 125-126, 231.

- Melissa Barden Dowling, "A Time to Regender: The Transformation of Roman Time," in Time and Uncertainty (Brill, 2004), p. 184.

- Strong, Roman Art, p. 231.

- Strong, Roman Art, pp. 287–291

- Yann Le Bohec, The Imperial Roman Army (Routledge, 2001, originally published 1989 in French), p. 251.

- Bohec, The Imperial Roman Army, p. 251.

- Toynbee, Death and Burial, p. 55.

- Graham Webster, The Roman Imperial Army of the First and Second Centuries A.D. (University of Oklahoma Press, 1985, 1998, 3rd edition), pp. 280–281.

- Pat Southern, The Roman Army: A Social and Institutional History (Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 296.

- Webster, The Roman Imperial Army, pp. 267, 280.

- Le Bohec, The Imperial Roman Army, p. 251.

- Le Bohec, The Imperial Roman Army, p. 192.

- translation and background at Livius.org: CIL XIII 8648 = AE 1952, 181 = AE 1953, 222 = AE 1955, 34

- Webster, The Roman Imperial Army, p.280.

- Le Bohec, The Imperial Roman Army, p. 125.

- Webster, The Roman Imperial Army, p. 280.

- Bohec, The Imperial Roman Army, p.251.

- "Final Farewell: The Culture of Death and the Afterlife". Museum of Art and Archaeology | College of Arts and Science | University of Missouri. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- Claudia, Flavia (9 January 2007). "Roman Beliefs about the Afterlife". Nova Roma. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- Foutz, Scott David. "Death and the Afterlife in Greco-Roman Religion". Theology WebSite. Archived from the original on 19 August 2000.

- Epictetus, Disc., III.xxiv.11.

- Epictetus, Disc., III.xxiv.84–87.

- Post sepulturam vanae manium ambages, omnibus a supremo die eadem quae ante primum, nec magis a morte sensus ullus aut corpori aut animae quam ante natalem. eadem enim vanitas in futurum etiam se propagat et in mortis quoque tempora ipsa sibi vitam mentitur, alias inmortalitatem animae, alias transfigurationem – VII.188

- Motto, A. L. (1995, January). Seneca on Death and Immortality. The Classical Journal, 50(4), 187–189.

- Si quis piorum minibus locus, si, ut sapientibus placet, non cum corpore extiguuntur magnae animae – XLVI