STS-37

STS-37, the eighth flight of the Space Shuttle Atlantis, was a six-day mission with the primary objective of launching the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory (CGRO), the second of the Great Observatories program which included the visible-spectrum Hubble Space Telescope, the Chandra X-ray Observatory and the infrared Spitzer Space Telescope.[1] The mission also featured two spacewalks, the first since 1985.

The Compton Gamma Ray Observatory after deployment, photographed from Atlantis's flight deck | |

| Mission type | Satellite deployment |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 1991-027A |

| SATCAT no. | 21224 |

| Mission duration | 5 days, 23 hours, 32 minutes, 44 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 4,002,559 kilometres (2,487,075 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 93 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Atlantis |

| Landing mass | 86,651 kilograms (191,033 lb) |

| Payload mass | 17,204 kilograms (37,928 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 5 |

| Members | |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 5 April 1991, 14:22:45 UTC |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39B |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | 11 April 1991, 13:55:29 UTC |

| Landing site | Edwards Runway 33 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee altitude | 450 kilometres (280 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 462 kilometres (287 mi) |

| Inclination | 28.45 degrees |

| Period | 93.7 minutes |

Left to right: Cameron, Apt, Nagel, Ross, Godwin | |

Crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Steven R. Nagel Third spaceflight | |

| Pilot | Kenneth D. Cameron First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | Linda M. Godwin First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 | Jerry L. Ross Third spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 3 | Jay Apt First spaceflight | |

Spacewalks

- Ross and Apt – EVA 1

- EVA 1 Start: 7 April 1991

- EVA 1 End: 7 April 1991

- Duration: 4 hours, 26 minutes

- Ross and Apt – EVA 2

- EVA 2 Start: 8 April 1991

- EVA 2 End: 8 April 1991

- Duration: 5 hours, 47 minutes

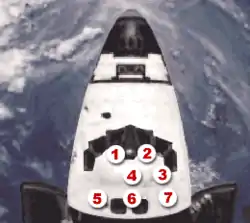

Crew seating arrangements

| Seat[2] | Launch | Landing |  Seats 1–4 are on the Flight Deck. Seats 5–7 are on the Middeck. |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Nagel | Nagel | |

| S2 | Cameron | Cameron | |

| S3 | Apt | Godwin | |

| S4 | Ross | Ross | |

| S5 | Godwin | Apt | |

Preparations and Launch

The STS-37 mission was successfully launched from launch pad 39B at 9:22:44AM EST on 5 April 1991 from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Resumption of the countdown after the T-9-minute hold was delayed about 4 minutes 45 seconds because of two possible weather-condition violations of the launch commit criteria (LCC). The first concerned the cloud ceiling being 500 feet less than the minimum of 8000 feet for a return-to-launch-site (RTLS) abort, and the second concerned the possible weather-condition (wind) effects on blast propagation. Both conditions were found acceptable and the launch countdown proceeded to a satisfactory launch to an inclination of 28.45 degrees.[3] Launch weight: 116,040 kilograms (255,820 lb).

Compton Gamma Ray Observatory

The primary payload, the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory (CGRO), was deployed on flight day 3. CGRO's high-gain antenna failed to deploy on command; it was finally freed and manually deployed by Ross and Apt during an unscheduled contingency space walk, the first since April 1985. The following day, the two astronauts performed the first scheduled space walk since November 1985 to test means for astronauts to move themselves and equipment about while maintaining the then-planned Space Station Freedom. CGRO science instruments were Burst and Transient Source Experiment (BATSE), Imaging Compton Telescope (COMPTEL), Energetic Gamma Ray Experiment Telescope (EGRET) and Oriented Scintillation Spectrometer Experiment (OSSE). CGRO was the second of NASA's four Great Observatories. The Hubble Space Telescope, deployed during Mission STS-31 in April 1990, was the first. CGRO was launched on a two-year mission to search for the high-energy celestial gamma ray emissions, which cannot penetrate Earth's atmosphere. At about 35,000 pounds, CGRO was the heaviest satellite to be deployed into low-Earth orbit from the Shuttle. It was also designed to be the first satellite that could be refueled in orbit by Shuttle crews. Five months after deployment, NASA renamed the satellite the Arthur Holly Compton Gamma Ray Observatory, or Compton Observatory, after the Nobel Prize-winning physicist who did important work in gamma ray astronomy.

Spacewalks

The first U.S. extravehicular activity (EVA) or spacewalk since 1985 was performed by Mission Specialists Jerry L. Ross and Jay Apt after six failed attempts to deploy the satellite's high-gain antenna. Repeated commands by ground controllers at the Payload Operations Control Center, Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD, and maneuvering of Atlantis and its Remote Manipulator System (RMS) robot arm, as well as CGRO's antenna dish, were to no avail in dislodging the boom. Ross and Apt were prepared for such a contingency, and Ross freed the antenna boom within 17 minutes after beginning the spacewalk. It was the first unscheduled contingency EVA since STS-51-D in April 1985. Deployment occurred about 18:35 EST, approximately 41⁄2 hours after it was scheduled.

The following day, on 8 April 1991, Ross and Apt made the first scheduled EVA since Mission STS-61-B in November 1985. The spacewalk was to test methods of moving crew members and equipment around the future Space Station Freedom. One of the experiments was to evaluate manual, mechanical and electrical power methods of moving carts around the outside of large structures in space. Although all three methods worked, the astronauts reported that propelling the cart manually or hand-over-hand worked best. With both EVAs, Ross and Apt logged 10 hours and 49 minutes walking in space during STS-37. Crew members also reported success with secondary experiments.

During the second EVA, a stainless steel palm restraint bar punctured the pressure bladder of Apt's right glove. However, the astronaut's hand and silk comfort glove partially sealed the hole, resulting in no detectable depressurization. In fact, the puncture was not noticed until postflight examination.[4]

Additional Payloads and Experiments

Secondary payloads included Crew and Equipment Translation Aids (CETA), which involved scheduled six-hour space walk by astronauts Ross and Apt (see above); Ascent Particle Monitor (APM); Shuttle Amateur Radio Experiment II (SAREX II); Protein Crystal Growth (PCG); Bioserve/Instrumentation Technology Associates Materials Dispersion Apparatus (BIMDA); Radiation Monitoring Equipment III (RME Ill); and Air Force Maui Optical Site (AMOS) experiment. Among the other payloads flown was the first flight of the Bioserve/Instrumentation Technology Associates Materials Dispersion Apparatus (BIMDA) to explore the commercial potential of experiments in the biomedical, manufacturing processes and fluid sciences fields, and the Protein Crystal Growth experiment, which has flown eight times before in various forms. Astronaut Pilot Kenneth Cameron was the primary operator of the Shuttle Amateur Radio Experiment (SAREX), although all five crew members participated as amateur radio operators. It was arguably the first time that the astronauts received fast scan amateur television video from the ham radio club station (W5RRR) at JSC.

Landing

11 April 1991, 06:55:29 PDT, Runway 33, Edwards Air Force Base, CA. Rollout distance: 6,364 feet (1,940 metres). Rollout time: 56 seconds. Landing originally scheduled for 10 April 1991, but delayed one day due to weather conditions at Edwards and Kennedy Space Center (KSC). Orbiter returned to KSC 18 April 1991. Landing weight: 86,227 kilograms (190,098 lb).

Due to an incorrect call on winds aloft, Atlantis landed 623 feet (190 metres) short of the lakebed runway's threshold marking. This did not present a problem, since the orbiter landed on the dry lake bed of Edwards, and a problem was not obvious to most viewers. Had the landing been attempted at the Kennedy Space Center, the result would have been a touchdown on the paved underrun preceding the runway and would have been much more obvious. Landing speed was 168 KEAS, 13 knots faster than the slowest landing of the Shuttle program, STS-28's 155 KEAS.[5]

Mission insignia

The three stars on the top and seven stars on the bottom of the insignia symbolize the flight's numerical designation in the Space Transportation System's mission sequence. The stars also represented the Amateur Radio term "73" or "Best regards", consistent with the fact that the entire crew had become licensed and operated the SAREX experiment while on orbit.

Wake-up calls

NASA began its longstanding tradition of waking up astronauts with music during Apollo 15.[6] Each track is specially chosen, often by the astronauts' families, and usually has a special meaning to an individual member of the crew, or is applicable to their daily activities.

| Day | Song | Artist/Composer | Played for |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 2 | Music by Marching Illini Band | University of Illinois | Steve Nagel |

| Day 3 | "The Marine Corp Hymn" | U. S. Naval Academy band | Ken Cameron |

| Day 4 | "Hail Purdue" | Purdue University Band | Jerry Ross |

| Day 5 | "10,000 Men of Harvard Want Victory Today" | Harvard University Glee Club | Jay Apt |

| Day 6 | "La Bamba" | Brass Rhythm and Reeds | Linda Goodwin |

| Day 7 | "Magnum PI" Theme with a greeting by Tom Selleck | Linda Goodiwn, a "big Selleck fan"[6] |

See also

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to STS-37. |

Notes

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- NASA (April 1991). "SPACE SHUTTLE MISSION STS-37 PRESS KIT" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- "STS-37". Spacefacts. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- STS-37 Mission Report,p.1,Robert W. Fricke,1991

- Robert W. Fricke (1 May 1991). "STS-37 Mission Report NASA-CR-193062, NAS 1.26:193062, JSC-08249". Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- NASA TM-2011-216142, Space Shuttle Missions Summary

- Fries, Colin. "Chronology of wakeup calls" (PDF).

.jpg.webp)