STS-9

STS-9 (also referred to as STS-41-A[1] and Spacelab 1) was the ninth NASA Space Shuttle mission and the sixth mission of the Space Shuttle Columbia. Launched on November 28, 1983, the ten-day mission carried the first Spacelab laboratory module into orbit.

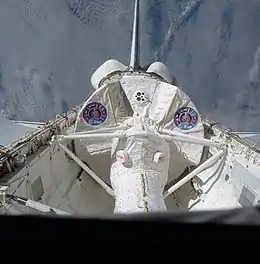

View of Columbia's payload bay, showing Spacelab. | |

| Mission type | Microgravity research |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 1983-116A |

| SATCAT no. | 14523 |

| Mission duration | 10 days, 6 hours, 47 minutes, 24 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 6,913,504 kilometres (4,295,852 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 167 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Columbia |

| Launch mass | 112,318 kilograms (247,618 lb) |

| Landing mass | 99,800 kilograms (220,021 lb) |

| Payload mass | 15,088 kilograms (33,263 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 6 |

| Members | |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | November 28, 1983, 16:00:00 UTC |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39A |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | December 8, 1983, 22:47:24 UTC |

| Landing site | Edwards Runway 17 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee altitude | 240 kilometres (149 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 253 kilometres (157 mi) |

| Inclination | 57.0 degrees |

| Period | 89.5 min |

L-R: Garriott, Lichtenberg, Shaw, Young, Merbold, Parker | |

STS-9 was also the last time the original STS numbering system was used until STS-26, which was designated in the aftermath of the 1986 Challenger disaster of STS-51-L. Under the new system, STS-9 would have been designated as STS-41-A. STS-9's originally planned successor, STS-10, was cancelled due to payload issues; it was instead followed by STS-41-B.

STS-9 sent the first non-U.S. citizen into space on the Shuttle, Ulf Merbold, becoming the first ESA and first West German citizen to go into space.[2]

Crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Sixth and last spaceflight | |

| Pilot | First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | Second and last spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 | First spaceflight | |

| Payload Specialist 1 | First spaceflight | |

| Payload Specialist 2 | First spaceflight | |

Backup crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Payload Specialist 1 | ||

| Payload Specialist 2 | ||

Support crew

- John E. Blaha (entry CAPCOM)

- Franklin R. Chang-Diaz

- Mary L. Cleave

- Anna L. Fisher

- William F. Fisher

- Guy S. Gardner (ascent CAPCOM)

- Chuck Lewis (Marshall CAPCOM)

- Bryan D. O'Connor

- Wubbo Ockels

Crew seating arrangements

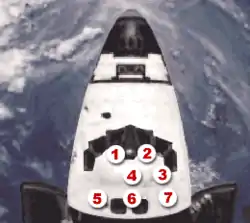

| Seat[3] | Launch | Landing |  Seats 1–4 are on the Flight Deck. Seats 5–7 are on the Middeck. |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Young | Young | |

| S2 | Shaw | Shaw | |

| S4 | Parker | Parker | |

| S5 | Garriott | Garriott | |

| S6 | Lichtenberg | Lichtenberg | |

| S7 | Merbold | Merbold | |

Mission background

STS-9's six-member crew, the largest of any human space mission at the time, included John W. Young, commander, on his second shuttle flight; Brewster H. Shaw, pilot; Owen Garriott and Robert A. Parker, both mission specialists; and Byron K. Lichtenberg and Ulf Merbold, payload specialists – the first two non-NASA astronauts to fly on the Space Shuttle. Merbold, a citizen of West Germany, was the first foreign citizen to participate in a shuttle flight. Lichtenberg was a researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Prior to STS-9, the scientist-astronaut Garriott had spent 56 days in orbit in 1973 aboard Skylab. Commanding the mission was veteran astronaut John Young, making his sixth and final flight over an 18-year career that saw him fly twice each in Gemini, Apollo, and the Shuttle, which included two journeys to the Moon and making him the most experienced space traveler to date. Young, who also commanded Columbia on its maiden voyage STS-1, was the first person to fly the same space vehicle into orbit more than once. STS-9 marked the only time that two pre-Shuttle era astronaut veterans (Garriott and Young) would fly on the same Space Shuttle mission.

The mission was devoted entirely to Spacelab 1, a joint NASA/European Space Agency (ESA) program designed to demonstrate the ability to conduct advanced scientific research in space. Both the mission specialists and payload specialists worked in the Spacelab module and coordinated their efforts with scientists at the Marshall Payload Operations Control Center (POCC), which was then located at the Johnson Space Center in Texas. Funding for Spacelab 1 was provided by the ESA.

Shuttle processing

After Columbia's return from STS-5 in November 1982, it received several modifications and changes in preparation for STS-9. Most of these changes were intended to support the Spacelab module and crew, such as the addition of a tunnel connecting the Spacelab to the orbiter's airlock, and additional provisions for the mission's six crew members, such as a galley and sleeping bunks. Columbia also received the more powerful Space Shuttle Main Engines introduced with Challenger, which were rated for 104% maximum thrust; its original main engines were later refurbished for use with Atlantis, which was still under construction at the time. Also added to the shuttle were higher capacity fuel cells and a Ku-band antenna for use with the Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS).[4]

The mission's original launch date of October 29, 1983 was scrubbed due to concerns with the exhaust nozzle on the right solid rocket booster (SRB). For the first time in the history of the shuttle program, the shuttle stack was rolled back to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB), where it was destacked and the orbiter returned to the Orbiter Processing Facility, while the suspect booster underwent repairs. The shuttle was restacked and returned to the launch pad on November 8, 1983.[4][5][6]

Mission summary

STS-9 launched successfully from Kennedy Space Center at 11 am EST on November 28, 1983.

The shuttle's crew was divided into two teams, each working 12-hour shifts for the duration of the mission. Young, Parker and Merbold formed the Red Team, while Shaw, Garriott and Lichtenberg made up the Blue Team. Usually, Young and Shaw were assigned to the flight deck, while the mission and payload specialists worked inside the Spacelab.

Over the course of the mission, 72 scientific experiments were carried out, spanning the fields of atmospheric and plasma physics, astronomy, solar physics, material sciences, technology, astrobiology and Earth observations. The Spacelab effort went so well that the mission was extended an additional day to 10 days, making it the longest-duration shuttle flight at that time. In addition, Garriott made the first ham radio transmissions by an amateur radio operator in space during the flight. This led to many further space flights incorporating amateur radio as an educational and back-up communications tool.

The Spacelab 1 mission was highly successful, proving the feasibility of the concept of carrying out complex experiments in space using non-NASA persons trained as payload specialists in collaboration with a POCC. Moreover, the TDRS-1 satellite, now fully operational, was able to relay significant amounts of data through its ground terminal to the POCC.

During orbiter orientation, four hours before re-entry, one of the flight control computers crashed when the RCS thrusters were fired. A few minutes later, a second crashed in a similar fashion, but was successfully rebooted. Young delayed the landing, letting the orbiter drift. He later testified: "Had we then activated the Backup Flight Software, loss of vehicle and crew would have resulted." Post-flight analysis revealed the GPCs (General Purpose Computers)[7] failed when the RCS thruster motion knocked a piece of solder loose and shorted out the CPU board. A GPC running BFS may or may not have the same soldering defect as the rest of the GPCs. Switching the vehicle to the BFS from normal flight control can happen relatively instantaneously, and that particular GPC running the BFS could also be affected by the same failure due to the soldering defect. If such a failure occurred, switching the vehicle back to normal flight control software on multiple GPCs from a single GPC running BFS takes a lot longer, in essence leaving the vehicle without any control at all during the change.

Columbia landed on Runway 17 at Edwards Air Force Base on December 8, 1983, at 3:47 pm PST, having completed 166 orbits and travelled 4.3 million miles (6.9×106 km) over the course of its mission. Right before landing, two of the orbiter's three auxiliary power units caught fire due to a hydrazine leak, but the orbiter nonetheless landed successfully. Columbia was ferried back to KSC on December 15. The leak was later discovered after it had burned itself out and caused major damage to the compartment. The shuttle was then sent off for an extensive renovation and upgrade program to bring it up to date with the newer Challenger orbiter as well as the upcoming Discovery and Atlantis. As a result, Columbia would not fly at all during 1984–85.

Launch attempts

| Attempt | Planned | Result | Turnaround | Reason | Decision point | Weather go (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 29 Oct 1983, 12:00:00 pm | scrubbed | — | technical | 19 Oct 1983, 12:00 am (T-43) | SRB nozzle issues. Launch and decision point times are approximate, dates are accurate. | |

| 2 | 28 Nov 1983, 11:00:00 am | success | 29 days, 22 hours, 60 minutes |

Mission insignia

The mission's main payload, Spacelab 1, is depicted in the payload bay of the Columbia. The nine stars and the path of the orbiter indicate the flight's numerical designation, STS-9.

See also

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- "Fun facts about STS numbering" Archived 2010-05-27 at the Wayback Machine. NASA/KSC. October 29, 2004. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- "STS-9". Spacefacts. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- "STS-9 Press Kit" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- Lewis, Richard (1984). The voyages of Columbia: the first true spaceship. Columbia University Press. pp. 204. ISBN 978-0-231-05924-4.

- "Shuttle Rollbacks". NASA. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- http://www.spaceshuttleguide.com/system/data_processing_system.htm

Further reading

- Long, Michael E. (September 1983). "Spacelab 1". National Geographic. Vol. 164 no. 3. pp. 301–307. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

External links

- STS-9 mission summary. NASA.

- STS-9 video highlights. NSS.

- "Space shuttle computer problems, 1981–1985". Risks Digest. January 20, 1989. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

.jpg.webp)