STS-31

STS-31 was the 35th mission of the American Space Shuttle program, which launched the Hubble Space Telescope astronomical observatory into Earth orbit. The mission used the Space Shuttle Discovery (the tenth for this orbiter), which lifted off from Launch Complex 39B on 24 April 1990 from Kennedy Space Center, Florida.

Discovery deploys the Hubble Space Telescope | |

| Mission type | Satellite deployment |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 1990-037A |

| SATCAT no. | 20579 |

| Mission duration | 5 days, 1 hour, 16 minutes, 6 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 3,328,466 kilometers (2,068,213 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 80 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Discovery |

| Launch mass | 117,586 kilograms (259,233 lb) |

| Landing mass | 85,947 kilograms (189,481 lb) |

| Payload mass | 11,878 kilograms (26,187 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 5 |

| Members | |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 24 April 1990, 12:33:51 UTC |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39B |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | 29 April 1990, 13:49:57 UTC |

| Landing site | Edwards Runway 22 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee altitude | 613 kilometres (381 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 615 kilometres (382 mi) |

| Inclination | 28.45 degrees |

| Period | 96.7 minutes |

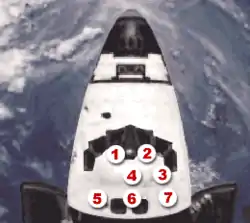

Left to right: Bolden, Hawley, Shriver, McCandless, Sullivan | |

Discovery's crew deployed the Hubble telescope on 25 April, and spent the rest of the mission tending to various scientific experiments in the Shuttle's payload bay and operating a set of IMAX cameras to record the mission. Discovery's launch marked the first time since January 1986 that two Space Shuttles had been on the launch pad at the same time – Discovery on 39B and Columbia on 39A.

Crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Loren J. Shriver Second spaceflight | |

| Pilot | Charles F. Bolden Jr. Second spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | Bruce McCandless II Second and last spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 | Steven A. Hawley Third spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 3 | Kathryn D. Sullivan Second spaceflight | |

Crew seating arrangements

| Seat[1] | Launch | Landing |  Seats 1–4 are on the Flight Deck. Seats 5–7 are on the Middeck. |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Shriver | Shriver | |

| S2 | Bolden | Bolden | |

| S3 | McCandless | Sullivan | |

| S4 | Hawley | Hawley | |

| S5 | Sullivan | McCandless | |

Crew notes

Initially, this mission was to be flown in August 1986 as STS-61-J using Atlantis, but was postponed by the Challenger disaster. John Young was originally assigned to command this mission,[2] which would have been his seventh spaceflight, but was reassigned to an administrative position and was replaced by Loren Shriver in 1988.[3]

Mission highlights

STS-31 was launched on 24 April 1990 at 8:33:51 am EDT. A launch attempt on 10 April was scrubbed at T-4 minutes for a faulty valve in auxiliary power unit (APU) number one. The APU was eventually replaced and the Hubble Space Telescope's batteries were recharged. On launch day, the countdown was briefly halted at T-31 seconds when Discovery's computers failed to shut down a fuel valve line on ground support equipment. Engineers ordered the valve closed and the countdown continued.[4]

The primary payload was the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), deployed in a 380 statute mile (612 kilometres (380 mi)) orbit. The shuttle's orbit in this mission was its highest orbit up to that date, in order for HST to be released near its operational altitude well outside the atmosphere. Discovery orbited the Earth 80 times during the mission.[5]

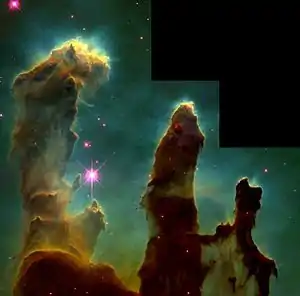

The main purpose of this mission was to deploy Hubble. It was designed to operate above the Earth's turbulent and obscuring atmosphere to observe celestial objects at ultraviolet, visible and near-infrared wavelengths. The Hubble mission was a joint NASA-ESA effort going back to the late 1970s.[6] The rest of the mission was devoted to photography and onboard experiments. To launch HST into an orbit that guaranteed longevity, Discovery soared to 600 kilometres (370 mi). The record height permitted the crew to photograph Earth's large-scale geographic features not apparent from lower orbits. Motion pictures were recorded by two IMAX cameras, and the results appeared in the 1994 IMAX film Destiny in Space.[7] Experiments included a biomedical technology study, advanced materials research, particle contamination and ionizing radiation measurements, and a student science project studying zero gravity effects on electronic arcs. Discovery's reentry from its higher than usual orbit required a deorbit burn of 4 minutes and 58 seconds, the longest in Shuttle history up to that time.[5]

During the deployment of Hubble, one of the observatory's solar arrays stopped as it unfurled. While ground controllers searched for a way to command HST to unreel the solar array, Mission Specialists McCandless and Sullivan began preparing for a contingency spacewalk in the event that the array could not be deployed through ground control. The array eventually came free and unfurled through ground control, while McCandless and Sullivan were pre-breathing inside the partially depressurized airlock.[8]

Secondary payloads included the IMAX Cargo Bay Camera (ICBC) to document operations outside the crew cabin and a handheld IMAX camera for use inside the orbiter. Also included were the Ascent Particle Monitor (APM) to detect particulate matter in the payload bay; a Protein Crystal Growth (PCG) experiment to provide data on growing protein crystals in microgravity, Radiation Monitoring Equipment III (RME III) to measure gamma ray levels in the crew cabin; Investigations into Polymer Membrane Processing (IPMP) to determine porosity control in the microgravity environment, and an Air Force Maui Optical Site (AMOS) experiment.[5]

The mission marked the flight of an 11-pound human skull, which served as the primary element of "Detailed Secondary Objective 469", also known as the In-flight Radiation Dose Distribution (IDRD) experiment. This joint NASA/DoD experiment was designed to examine the penetration of radiation into the human cranium during spaceflight. The female skull was seated in a plastic matrix, representative of tissue, and sliced into ten layers. Hundreds of thermo-luminescent dosimeters were mounted in the skull's layers to record radiation levels at multiple depths. This experiment, which also flew on STS-28 and STS-36, was located in the shuttle's mid-deck lockers on all three flights, recording radiation levels at different orbital inclinations.[9]

Discovery landed on 29 April 1990 at 6:49:57 am PDT, landing on Runway 22 at Edwards Air Force Base in California. The rollout distance was 2,705 metres (8,875 ft) and took 61 seconds. This also marked the first use of carbon brakes. Discovery returned to KSC on 7 May 1990.[10]

| Attempt | Planned | Result | Turnaround | Reason | Decision point | Weather go (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 Apr 1990, 12:00:00 am | scrubbed | — | technical | (TT-4) | faulty valve in Auxiliary Power Unit (APU) Number One.[4] | |

| 2 | 24 Apr 1990, 12:33:51 pm | delayed, successful | 14 days, 12 hours, 34 minutes | technical | (TT-31 seconds) | countdown was held at T-31 seconds when a fuel valve line on ground support equipment failed to shut automatically. The valve was shut manually and the countdown was resumed.[4] |

Wake-up calls

NASA began a tradition of playing music to astronauts during the Gemini program, which was first used to wake up a flight crew during Apollo 15. Each track is specially chosen, often by their families, and usually has a special meaning to an individual member of the crew, or is applicable to their daily activities.[11]

| Flight Day | Song | Artist/Composer |

|---|---|---|

| Day 2 | "Space is Our World" | Private Numbers |

| Day 3 | "Shout" | Otis Day and the Knights |

| Day 4 | "Kokomo" | Beach Boys |

| Day 5 | "Cosmos" | Frank Hayes |

| Day 6 | "Rise and Shine" | Raffi |

Gallery

Hubble at the pad.

Hubble at the pad. Liftoff of Discovery with the Hubble Space Telescope on board.

Liftoff of Discovery with the Hubble Space Telescope on board. Low hover position.

Low hover position. High over Cuba.

High over Cuba. Solar array deployment.

Solar array deployment. Hubble drifts away over Peru.

Hubble drifts away over Peru. Florida and the Bahamas.

Florida and the Bahamas. Discovery returns home.

Discovery returns home.

See also

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- Becker, Joachim. "Spaceflight mission report: STS-31". SPACEFACTS. Archived from the original on 7 January 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- Janson, Bette R.; NASA; Scientific and Technical Information Division (1 March 1988). Ritchie, Eleanor H.; Saegesser, Lee D. (eds.). Astronautics and Aeronautics, 1985: A Chronology (PDF). Washington, DC.: United States Government Printing Office. p. 282. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 January 2021.

- Carr, Jeffry (17 March 1988). "JSC News Release Log 1988" (PDF). Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. Houston, Texas: NASA. p. 88-008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2017.

- Office of Safety, Reliability, Maintainability and Quality Assurance (15 October 1990). "Misson Safety Evaluation Report for STS-31 - Postflight Edition" (PDF). Washington, DC: NASA. p. 7-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 January 2021.

- Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center (May 1990). "STS-31 Space Shuttle Mission Report" (PDF). Houston, Texas: NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 January 2021.

- Gavaghan, Helen (7 July 1990). "Design flaw cripples Hubble telescope". New Scientist (1724). Archived from the original on 7 January 2021.

- "Camera, ICBC, 70mm, IMAX". National Air and Space Museum. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 7 January 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- Goodman, John L.; Walker, Stephen R. (31 January 2009). Hubble Servicing Challenges Drive Innovation of Shuttle Rendezvous Technique (PDF). 32nd Annual AAS Guidance and Control Conference. Breckenridge, Colorado: AAS Publications Office. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 January 2021.

- MacKnight, Nigel (31 December 1991). Space Year 1991: The Complete Record of the Year's Space Events. Osceola, Wis.: Motorbooks International. p. 41. ISBN 978-0879384821.

- Ryba, Jeanne (23 November 2007). "STS-31". Mission Archives. NASA. Archived from the original on 7 January 2021.

- Fries, Colin (13 March 2015). "Chronology of Wakeup Calls" (PDF). History Division. NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

.jpg.webp)