STS-43

STS-43, the ninth mission for Space Shuttle Atlantis, was a nine-day mission whose primary goal was launching the fourth Tracking and Data Relay Satellite, TDRS-E. The flight also tested an advanced heatpipe radiator for potential use on the then-future space station and conducted a variety of medical and materials science investigations.

Atlantis deploying TDRS-E | |

| Mission type | Satellite deployment Technology |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | 1991-054A |

| SATCAT no. | 21638 |

| Mission duration | 8 days, 21 hours, 21 minutes, 25 seconds |

| Distance travelled | 5,955,217 kilometers (3,700,400 mi) |

| Orbits completed | 142 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Atlantis |

| Landing mass | 89,239 kilograms (196,738 lb) |

| Payload mass | 21,067 kilograms (46,445 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 5 |

| Members | |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 2 August 1991, 15:01:59 UTC |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39A |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | 11 August 1991, 12:23:25 UTC |

| Landing site | Kennedy SLF Runway 15 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee altitude | 301 kilometres (187 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 306 kilometres (190 mi) |

| Inclination | 28.45 degrees |

| Period | 90.6 min |

Left to right: Lucid, Adamson, Blaha, Low, Baker | |

Crew

| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | John E. Blaha Third spaceflight | |

| Pilot | Michael A. Baker First spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | Shannon W. Lucid Third spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 2 | G. David Low Second spaceflight | |

| Mission Specialist 3 | James C. Adamson Second and last spaceflight | |

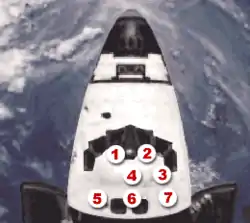

Crew seating arrangements

| Seat[1] | Launch | Landing |  Seats 1–4 are on the Flight Deck. Seats 5–7 are on the Middeck. |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Blaha | Blaha | |

| S2 | Baker | Baker | |

| S3 | Lucid | Adamson | |

| S4 | Low | Low | |

| S5 | Adamson | Lucid | |

Preparations and Launch

The launch took place on 2 August 1991, 11:01:59 am EDT. Launch was originally set for 23 July but was moved to 24 July to allow time to replace a faulty integrated electronics assembly that controls orbiter/external tank separation. The mission was postponed again about five hours before liftoff on 24 July due to a faulty main engine controller on the number three main engine. The controller was replaced and retested; launch was reset for 1 August. Liftoff set for 11:01 am delayed due to cabin pressure vent valve reading and postponed at 12:28 pm due to unacceptable return-to-launch site weather conditions. Launch finally occurred on 2 August 1991 without further delays. Launch weight: 117,650 kilograms (259,370 lb).

Mission Highlights

The primary payload, Tracking and Data Relay Satellite-5 (TDRS-5 or TDRS-E), attached to an Inertial Upper Stage (IUS), was deployed about six hours into flight, and the IUS propelled the satellite into geosynchronous orbit. TDRS-5 became the fourth member of the orbiting TDRS cluster. Secondary payloads were Space Station Heat Pipe Advanced Radiator Element II (SHARE II); Shuttle Solar Backscatter Ultra-Violet (SSBUV) instrument; Tank Pressure Control Equipment (TPCE) and Optical Communications Through Windows (OCTW). Other experiments included Auroral Photography Experiment (APE-B) Protein Crystal Growth Ill (PCG Ill); Bioserve / Instrumentation Technology Associates Materials Dispersion Apparatus (BIMDA); Investigations into Polymer Membrane Processing (IPMP); Space Acceleration Measurement System (SAMS); Solid Surface Combustion Experiment (SSCE); Ultraviolet Plume imager (UVPI); and the Air Force Maui Optical Site (AMOS) experiment.[2]

TDRS E, which became TDRS-5 on orbit, was successfully boosted to geosynchronous orbit at more than 22,000 miles (35,400 kilometres (22,000 mi)) above Earth by two firings of the Inertial Upper Stage (IUS) booster, the last of which occurred approximately 12½ hours into the mission. TDRS then deployed its antennas and solar panels, and separation from the IUS took place less than 45 minutes later.

The TDRS network of satellites provides the vital communication link between Earth and low-orbiting spacecraft such as the Space Shuttle. Until the STS-43 deployment, there were three TDRS spacecraft on orbit above the equator: two were in the west position over the Pacific Ocean, southwest of Hawaii. TDRS-4 was in the east position over the northeast corner of Brazil. TDRS-B was lost in the Challenger accident in 1986. After STS-43, the two satellites in the west became on-orbit spares; TDRS-5, after activation, checkout and calibration, officially became the primary provider of services in the west location on 7 October 1991. It was stationed at 175 degrees west longitude.

Previously, orbiting spacecraft could communicate with Earth only when in sight of a ground tracking station – about 15 percent of each orbit. The TDRS network allows communication from 85 to 100 percent of an orbit, depending on the spacecraft's altitude.

The crew was kept busy with the operation of varied experiments during the nine-day flight. The Space Station Heat Pipe Advanced Radiator Element II (SHARE-II) experiment tested a natural cooling process for transferring thermal energy that could serve as a cooling system for Space Station Freedom. The Solid Surface Combustion Experiment provided some answers about how fire behaves in microgravity. The crew also activated other previously flown materials science experiments and participated in medical experiments in support of long-duration flights. One test showed that optical fibers could provide video and audio links between the flight deck and the payload bay.

Crew members in space and flight controllers on the ground demonstrated their ingenuity when they adapted a camera part to replace one that had not been packed for the mission.

The mission was also notable for being the first one to send an e-mail from space. On 9 August 1991, astronauts Lucid and Adamson used AppleLink to write an e-mail from a Macintosh Portable addressed to Marsha Ivins at Johnson Space Center.[3] The message read:

Hello Earth! Greetings from the STS-43 Crew. This is the first AppleLink from space. Having a GREAT time, wish you were here,...send cryo and RCS! Hasta la vista, baby,...we'll be back!

The crew experienced some minor problems, none of them critical to the safety or success of the mission. A cooling system for Auxiliary Power Unit (APU) 2 failed to activate during an on-orbit test. APU 2 is one of three redundant systems which provide hydraulic pressurization to orbiter steering systems during entry and landing. APU 2 was still available for use in landing.

Landing: 11 August 1991, 8:23:25 am EDT, Runway 15, Kennedy Space Center, FL. Rollout distance: 9,890 feet. Rollout time: 60 seconds. First landing scheduled at KSC since 61-C in January 1986 (which was diverted to Edwards). Landing weight: 88,944 kilograms (196,088 lb).

Mission insignia

According to the mission's official Press Kit, the STS-43 insignia portrays the evolution and continuity of the U.S. space program by highlighting thirty years of American crewed spaceflight experience, from Project Mercury to the Space Shuttle. The emergence of the shuttle Atlantis from the outlined configuration of the Mercury space capsule commemorates this special relationship. The energy and momentum of launch are conveyed by the gradations of blue which mark the shuttle's ascent from Earth to space. Once in Earth orbit, Atlantis' cargo bay opens to reveal the Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS) which appears in gold emphasis against the white wings of Atlantis and the stark blackness of space. A primary mission objective, the Tracking and Data Relay Satellite System (TDRSS) will enable almost continuous communication from Earth to space for future space shuttle missions. The stars on the insignia are arranged to suggest this mission's numerical designation, with four stars left of Atlantis and three to the right.[4]

Wake-up calls

NASA began its longstanding tradition of waking up astronauts with music during Apollo 15. Each track is specially chosen, often by the astronauts' families, and usually has a special meaning to an individual member of the crew, or is applicable to their daily activities.

| Day | Song | Artist/Composer | Played for |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 2 | Back in the High Life | Steve Winwood | |

| Day 3 | Excerpts from "Dances with the Wolves" soundtrack | James Adamson | |

| Day 4 | Custom music medley sung by friends of the STS-43 crew from Rockwell-Downey, in

California. |

||

| Day 5 | Music of the Clear Lake High School Orchestra playing selections from "Phantom of the

Opera". Commander John Blaha's daughter, Caroline, plays in the orchestra. |

Andrew Lloyd Webber | John Blaha |

| Day 6 | What a Wonderful World | Louis Armstrong | |

| Day 7 | Cowboy in the Continental Suit | Chris LeDoux | James Adamson |

| Day 8 | Washington and Lee University fight song | G. David Low | |

| Day 9 | Sounds from Shannon Lucid's backyard |

See also

References

- "STS-43". Spacefacts. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/shuttle/shuttlemissions/archives/sts-43.html

- "Macintosh Portable: Used in Space Shuttle". support.apple.com. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- https://www.jsc.nasa.gov/history/shuttle_pk/pk/Flight_042_STS-043_Press_Kit.pdf

External links

- NASA mission summary

- STS-43 Video Highlights

- STS-43 crew in Werner Herzog's film The Wild Blue Yonder

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

.jpg.webp)