Sacred prostitution

Sacred prostitution, temple prostitution, cult prostitution,[1] and religious prostitution are general terms for a rite consisting of paid intercourse performed in the context of religious worship, possibly as a form of fertility rite or divine marriage (hieros gamos). Scholars prefer the terms "sacred sex" or "sacred sexual rites" in cases where payment for services is not involved.

The historicity of literal sacred prostitution, particularly in some places and periods, is a controversial topic within the academic world.[2] Mainstream historiography has traditionally considered it a probable reality, based on the abundance of ancient sources and chroniclers detailing its practices,[1][3] although it has proved harder to differentiate between true prostitution and sacred sex without remuneration.[4] Authors have also interpreted evidence as secular prostitution administered in the temple under the patronage of fertility deities, not as an act of religious worship by itself.[5][6] In contrast, some modern gender researchers have challenged it entirely as the result of mistranslation and cultural slander.[1][3]

Outside academic debate, sacred prostitution has been adopted as a sign of distinction by sex workers, modern pagans and practitioners of sex magic.[7][8][9] Social authors have both decried it as a subproduct of patriarchy[1][3] and embraced it as a symbol of women's empowerment.[10][11]

Ancient Near East

Ancient Near Eastern societies along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers featured many shrines and temples or houses of heaven dedicated to various deities. The 5th-century BC historian Herodotus's account and some other testimony from the Hellenistic Period and Late Antiquity suggest that ancient societies encouraged the practice of sacred sexual rites not only in Babylonia and Cyprus, but throughout the Near East.

The work of gender researchers like Daniel Arnaud,[12] Julia Assante[13] and Stephanie Budin[14] has cast the whole tradition of scholarship that defined the concept of sacred prostitution into doubt. Budin regards the concept of sacred prostitution as a myth, arguing taxatively that the practices described in the sources were misunderstandings of either non-remunerated ritual sex or non-sexual religious ceremonies, possibly even mere cultural slander.[15] Although popular in modern times, this view has not gone without being criticized in its methodological approach,[16] including accusations of an ideological agenda.[7] A more nuanced view espoused by Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge, who also called for caution on Budin's categorical denial, suggests that some form of temple prostitution might have existed in the Near East, though not in the Greek or Roman worlds in classical or Hellenistic times.[17]

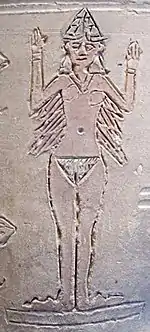

Sumer

Through the twentieth century, scholars generally believed that a form of sacred marriage rite (hieros gamos) was staged between the kings in the ancient Near Eastern region of Sumer and the high priestesses of Inanna, the Sumerian goddess of sexual love, fertility, and warfare, later called Ishtar. The king would couple with the priestess to represent the union of Dumuzid with Inanna.[18] According to the noted Assyriologist Samuel Noah Kramer, the kings would further establish their legitimacy by taking part in a ritual sexual act in the temple of the fertility goddess Ishtar every year on the tenth day of the New Year festival Akitu.[19]

However, no certain evidence has survived to prove that sexual intercourse was included, despite many popular descriptions of the habit.[20] It is possible that these unions never occurred but were embellishments to the image of the king; hymns which praise Middle Eastern kings for coupling with the goddess Ishtar often speak of him as running 320 kilometres, offering sacrifices, feasting with the sun-god Utu, and receiving a royal crown from An, all in a single day.[21] Some modern historians argue in the same direction,[15][22][23] though their posture has been disputed.[18]

Babylonia

According to Herodotus, the rites performed at these temples included sexual intercourse, or what scholars later called sacred sexual rites:

The foulest Babylonian custom is that which compels every woman of the land to sit in the temple of Aphrodite and have intercourse with some stranger at least once in her life. Many women who are rich and proud and disdain to mingle with the rest, drive to the temple in covered carriages drawn by teams, and stand there with a great retinue of attendants. But most sit down in the sacred plot of Aphrodite, with crowns of cord on their heads; there is a great multitude of women coming and going; passages marked by line run every way through the crowd, by which the men pass and make their choice. Once a woman has taken her place there, she does not go away to her home before some stranger has cast money into her lap, and had intercourse with her outside the temple; but while he casts the money, he must say, "I invite you in the name of Mylitta". It does not matter what sum the money is; the woman will never refuse, for that would be a sin, the money being by this act made sacred. So she follows the first man who casts it and rejects no one. After their intercourse, having discharged her sacred duty to the goddess, she goes away to her home; and thereafter there is no bribe however great that will get her. So then the women that are fair and tall are soon free to depart, but the uncomely have long to wait because they cannot fulfil the law; for some of them remain for three years, or four. There is a custom like this in some parts of Cyprus.[24]

The British anthropologist James Frazer accumulated citations to prove this in a chapter of his magnum opus The Golden Bough (1890–1915),[25] and this has served as a starting point for several generations of scholars. Frazer and Henriques distinguished two major forms of sacred sexual rites: temporary rite of unwed girls (with variants such as dowry-sexual rite, or as public defloration of a bride), and lifelong sexual rite.[26] However, Frazer took his sources mostly from authors of Late Antiquity (i.e. 150–500 AD), not from the Classical or Hellenistic periods.[27] This raises questions as to whether the phenomenon of temple sexual rites can be generalized to the whole of the ancient world, as earlier scholars typically did.

In Hammurabi's code of laws, the rights and good name of female sacred sexual priestesses were protected. The same legislation that protected married women from slander applied to them and their children. They could inherit property from their fathers, collect income from land worked by their brothers, and dispose of property. These rights have been described as extraordinary, taking into account the role of women at the time.[28]

Terms associated with temple prostitution in Sumeria and Babylonia

All translations are sourced from the Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary.[29] Akkadian terms were used in the Akkadian Empire, Assyria, and Babylonia. The terms themselves come from lexical profession lists on tablets dating back to the Early Dynastic period. Note that by convention Akkadian is italicized and determinatives are written as superscripts.

| English | Sumerian | Akkadian | Signs | Cuneiform |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbess | nin-diĝir | ēntu | SAL.TUG2.AN | 𒊩𒌆𒀭 |

| Priestess | lukur | nadītu | SAL.ME | 𒊩𒈨 |

| Nun | nugig | qadištu | NU.GIG | 𒉡𒍼 |

| Hierodule Priestess | nubar | kulmašītu | NU.BAR | 𒉡𒁇 |

| Cult Prostitute | amalu | ištaru | GA2×AN.LUL | 𒂼𒈜 |

| A Class of Women | sekrum | sekretu | ZI.IG.AŠ | 𒍣𒅅𒀸 |

| Prostitute | geme2karkid | harīmtu | SAL×KURTE.KID | 𒊩𒆳𒋼𒆤 |

Hittites

The Hittites practiced sacred prostitution as part of a cult of deities, including the worship of a mated pair of deities, a bull god and a lion goddess, while in later days it was the mother-goddess who became prominent, representing fertility, and (in Phoenicia) the goddess who presided over human birth.[30]

Phoenicia

At the Etruscan site of Pyrgi, a center of worship of the eastern goddess Astarte, archaeologists identified a temple consecrated to her and built with at least 17 small rooms that may have served as quarters for temple prostitutes.[31] Similarly, a temple dedicated to her equated goddess Atargatis in Dura-Europos, was found with nearly a dozen small rooms with low benches, which might have used either for sacred meals or sacred services of women jailed in the temple for adultery.[31][32]

Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible uses two different words for prostitute, zonah (זונה)[33] and kedeshah (or qedesha) (קדשה).[33] The word zonah simply meant an ordinary prostitute or loose woman.[33] But the word kedeshah literally means set apart (in feminine form), from the Semitic root Q-D-Sh (קדש) meaning holy, consecrated or set apart.[33] Nevertheless, zonah and qedeshah are not interchangeable terms: the former occurs 93 times in the Bible,[34] whereas the latter is only used in three places,[35] conveying different connotations.

This double meaning has led to the belief that kedeshah were not ordinary prostitutes, but sacred harlots who worked out of fertility temples.[36] However, the lack of solid evidence[23][37][38] has indicated that the word might refer to prostitutes who offered their services in the vicinity of temples, where they could attract a larger number of clients.[36] The term might have originated as consecrated maidens employed in Canaanite and Phoenician temples, which became synonymous with harlotry for Biblical writers.[32]

In any case, the translation of sacred prostitute has continued, however, because it explains how the word can mean such disparate concepts as sacred and prostitute.[39] As put by DeGrado, "neither the interpretation of the קדשה as a "priestess-not-prostitute" (so Westenholz) nor as a "prostitute-not-priestess" (so Gruber) adequately represents the semantic range of Hebrew word in biblical and post-biblical Hebrew."[39]

Male prostitutes were called kadesh or qadesh (literally: male who is set apart).[40] The Hebrew word kelev (dog) below may also signify a male dancer or prostitute.[41]

The Law of Moses (Deuteronomy) was not universally observed in Hebrew culture under the rule of King David's dynasty, as recorded in Kings. In fact Judah had lost "the Book of the Law". During the reign of King Josiah, the high priest Hilkiah discovers it in "the House of the Lord" and realizes that the people have disobeyed, particularly regarding prostitution.[42][43] Examples of male prostitution ("sodomites" in KJV, GNV: see Bible translations into English) being banned under King Josiah are recorded to have been commonplace since the reign of King Rehoboam of Judah (King Solomon's son).[44]

Most Bible translations do not reflect the latest scholarship and modern translations refer to King Josiah's bans on "male temple prostitutes" [NRSV] or similarly "male shrine prostitutes" [NIV], whereas older translations refer to the ban of "Sodomites" and "the Houses of the Sodomites" [KJV, GNV]. Under the uncentralised religious practices that were commonplace, homosexual prostitution experienced a degree of cultural acceptance along with heterosexual prostitution among the Hebrew tribes, but under the religious reforms prostitution was not allowed in conjunction with the worship of Yahweh, where these had been expressly forbidden in Deuteronomy, their sacred Book of Law under King Josiah.[45]

None of the daughters of Israel shall be a kedeshah, nor shall any of the sons of Israel be a kadesh. You shall not bring the hire of a prostitute (zonah) or the wages of a dog (kelev) into the house of the Lord your God to pay a vow, for both of these are an abomination to the Lord your God.

In the Book of Ezekiel, Oholah and Oholibah appear as the allegorical brides of God who represent Samaria and Jerusalem. They became prostitutes in Egypt, engaging in prostitution from their youth. The prophet Ezekiel condemns both as guilty of religious and political alliance with heathen nations.[46]

Ancient Greece and Hellenistic world

Ancient Greece

In ancient Greece, sacred prostitution was known in the city of Corinth where the Temple of Aphrodite employed a significant number of female servants, hetairai, during classical antiquity.[47]

The Greek term hierodoulos or hierodule has sometimes been taken to mean sacred holy woman, but it is more likely to refer to a former slave freed from slavery in order to be dedicated to a god.[15]

In the temple of Apollo at Bulla Regia, a woman was found buried with an inscription reading: "Adulteress. Prostitute. Seize (me), because I fled from Bulla Regia." It has been speculated she might be a woman forced into sacred prostitution as a punishment for adultery.[31]

Hellenistic world

In the Greek-influenced and colonized world, "sacred prostitution" was known in Cyprus[48] (Greek-settled since 1100 BC), Sicily[49] (Hellenized since 750 BC), in the Kingdom of Pontus[50] (8th century BC) and in Cappadocia (c. 330 BC hellenized).[51] 2 Maccabees 6:4–5 describes sacred prostitution in the Hebrew temple under the reign of the Hellenistic ruler Antiochus IV Epiphanes.

Ancient Rome and late antiquity

Ancient Rome

Late antiquity

The Roman emperor Constantine closed down a number of temples to Venus or similar deities in the 4th century AD, as the Christian church historian Eusebius proudly noted.[52] Eusebius also claimed that the Phoenician cities of Aphaca and Heliopolis (Baalbek) continued to practise temple prostitution until the emperor Constantine put an end to the rite in the 4th century AD.[52]

Asia

India

In Southern India and the eastern Indian state of Odisha, devadasi is the practice of hierodulic prostitution, with similar customary forms such as basavi,[53] and involves dedicating pre-pubescent and young adolescent girls from villages in a ritual marriage to a deity or a temple, who then work in the temple and function as spiritual guides, dancers, and prostitutes servicing male devotees in the temple. The devadasis were originally seen as intercessors who allowed upper-caste men to have contact with the gods. Though they did develop sexual relations with other men, they were not looked upon with lust. Before Muslim rule in the 14th century, they could live an existence apart from the men, with inheritance rights, wealth and influence, as well as living outside of the dangers of Indian marriage.[54]

The system was criticised by British rulers, leading to decline in support for the system and the devadasis were forced into entering prostitution for survival.[55] Many scholars have stated that the Hindu scriptures do not mention the system.[56] Human Rights Watch also reports claim that devadasis are forced into this service and, at least in some cases, to practice prostitution for upper-caste members.[57] Various state governments in India enacted laws to ban this practice both prior to India's independence and more recently. They include Bombay Devdasi Act, 1934, Devdasi (Prevention of dedication) Madras Act, 1947, Karnataka Devdasi (Prohibition of dedication) Act, 1982, and Andhra Pradesh Devdasi (Prohibition of dedication) Act, 1988.[58] However, the tradition continues in certain regions of India, particularly the states of Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh.[59]

Japan

Sacred prostitution was once practised by the miko within traditional Shinto in Japan. There were once Shinto beliefs that prostitution was sacred, and there used to be lodgings for the temple prostitutes on the shrine grounds. This traditional practise came to an end during the beginning of the Meiji era, due to the encroachment of Western Christian morality, and the government implementing the Shinbutsu bunri; which, among other things, drastically decreased the roles of the miko, and modified Shinto beliefs until it became what is now colloquially referred to as State Shinto.[60][61]

Indonesia

Mesoamerica and South America

.jpg.webp)

Maya

The Maya maintained several phallic religious cults, possibly involving homosexual temple prostitution.[62]

Aztec

Much evidence for the religious practices of the Aztec culture was destroyed during the Spanish Conquest, and almost the only evidence we have for the practices of their religion is from hostile Spanish accounts. The Franciscan Spanish Friar Bernardino de Sahagún learned their language and spent more than 50 years studying the culture. He wrote that they participated in religious festivals and rituals, as well as performing sexual acts as part of religious practice. This may be evidence for the existence of sacred prostitution in Mesoamerica, or it may be either confusion, or accusational polemic. He also speaks of kind of prostitutes named ahuianime ("pleasure girls"), whom he described as "an evil woman who finds pleasure in her body... [A] dissolute woman of debauched life."[63]

It is agreed that the Aztec god Xochipili (taken from both Toltec and Maya cultures) was both the patron of homosexuals and homosexual prostitutes.[64][65][66][67] Xochiquetzal was worshiped as goddess of sexual power, patroness of prostitutes and artisans involved in the manufacture of luxury items.[68][69][70]

Recent Western occurrences

In the 1970s and early 1980s, some religious cults practised sacred prostitution as an instrument to recruit new converts. Among them was the cult Children of God, also known as The Family, who called this practice "Flirty Fishing". They later abolished the practice due to the growing AIDS epidemic.[73]

In Ventura County, California, Wilbur and Mary Ellen Tracy established their own temple, the Church Of The Most High Goddess, in the wake of what they described as a divine revelation. Sexual acts played a fundamental role in the church's sacred rites, which were performed by Mary Ellen Tracy herself in her assumed role of High Priestess.[74] Local newspaper articles about the Neopagan church quickly got the attention of local law enforcement officials, and in April 1989, the Tracys' house was searched and the couple arrested on charges of pimping, pandering and prostitution. They were subsequently convicted in a trial in state court and sentenced to jail terms: Wilbur Tracy for 180 days plus a $1,000.00 fine; Mary Ellen Tracy for 90 days plus mandatory screening for STDs.[75][76]

Some modern sacred prostitutes act as sexual surrogates as a form of therapy. In places where prostitution is illegal, sacred prostitutes may be paid as therapists, escorts, or performers.[77]

Modern views

According to Avaren Ipsen, from Berkeley University's Commission on the Status of Women, the myth of sacred prostitution works as "an enormous source of self-esteem and as a model of sex positivity" to many sex workers.[7] She compared this situation to the figure of Mary Magdalene, whose status as a prostitute, though short-lived according to Christian texts and disputed among academics, has been celebrated by sex working collectives (among them Sex Workers Outreach Project USA) in an effort to de-stigmatize their job.[7] Ipsen speculated that academic currents trying to deny sacred prostitution are ideologically motivated, attributing them to the "desires of feminists, including myself, to be 'decent.'"[7]

In her book The Sacred Prostitute: Eternal Aspect of the Feminine, psychoanalyst Nancy Qualls-Corbett praised sacred prostitution as an expression of female sexuality and a bridge between the latter and the divine, as well as a rupture from mundane sexual degradation. "[The sacred prostitute] did not make love in order to obtain admiration or devotion from the man who came to her... She did not require a man to give her a sense of her own identity; rather this was rooted in her own womanliness."[78] Qualls also equated censuring sacred prostitution to demonize female sexuality and vitality. "In her temple, men and women came to find life and all that it had to offer in sensual pleasure and delight. But with the change in cultural values and the institutionalization of monotheism and patriarchy, the individual came to the House of God to prepare for death."[79]

This opinion is shared by several schools of modern Paganism.[7][9] among them Wicca,[80] for whom sacred prostitution, independently from its historical backing, embodies the sacralization of sex and a celebration of the communion between female and male sexuality.[9] This practice is associated to spiritual healing and sex magic.[80] Within secular thinking, philosopher Antonio Escohotado is a popular adept of this current, favoring particularly the role of ancient sacred prostitutes and priestesses of Ishtar. In his seminal work Rameras y esposas, he extols them and their cult as symbols of female empowerment and sexual freedom.[10]

Actress Susie Lamb approached sacred prostitution in her 2014 performance Horae: Fragments of a Sacred History of Prostitution, in which she points out its value to challenge gender roles. "The idea of sacred prostitution is almost entirely incomprehensible to the modern imagination. It involved women having sex as an act of worship... The relationship between men and women in this ancient tradition is based on respect for the woman. She was seen as a powerful person."[11]

See also

References

- Schulz, Matthias (26 March 2010). "Sex in the Service of Aphrodite: Did Prostitution Really Exist in the Temples of Antiquity?". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- Cooper 1971, pp. 18–19.

- Stol 2016, pp. 419–435.

- Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Tamar, Qedesha, Qadishtu, and Sacred Prostitution in Mesopotamia, The Harvard Theological Review 82, 198

- Martin Gruber, Hebrew Qedesha and her Canaanite and Akkadian Cognates, Ugarit-Forschungen 18, 1986

- Gerda Lerner, The Origin of Prostitution in Ancient Mesopotamia, Signs 11, 1986

- Ipsen 2014

- Qualls-Corbett 1988, pp. 14,24.

- Pike 2004, pp. 122, 126–127

- Escohotado 2018.

- Keating, Sara (20 February 2017). "'Sacred Prostitution': An ancient tradition based on respect for the woman". The Irish Times. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Arnaud 1973, pp. 111–115.

- Assante 2003.

- Budin 2008.

- Budin 2008; more briefly the case that there was no sacred prostitution in Greco-Roman Ephesus Baugh 1999; see also the book review by Vinciane Pirenne-Delforge, Bryn Mawr Classical Review, April 28, 2009.

- Rickard 2015.

- Pirenne-Delforge, Vinciane (April 2009). "Review of: The Myth of Sacred Prostitution in Antiquity". Bryn Mawr Classical Review. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- Day 2004, pp. 2–21

- Kramer 1969.

- Frazer 1922, Chapter 31: Adonis in Cyprus.

- Sweet 1994, pp. 85–104.

- Assante 2003, pp. 13–47.

- Yamauchi1973, pp. 213–222.

- Herodotus, vol.1 p.199.

- Frazer 1922, abridged ed. Chapter 31: Adonis in Cyprus; see also the more extensive treatment Frazer 1914, 3rd ed. volumes 5 and 6. Frazer's argument and citations are reproduced in slightly clearer fashion by Henriques 1961, vol. I, ch. 1

- Henriques 1961, vol. I, ch. 1.

- Herodotus and Strabo are the only sources mentioned by Frazer that were active prior to the 2nd century AD; his other sources include Athenaeus, pseudo-Lucian, Aelian, and the Christian church historians Sozomen and Socrates of Constantinople.

- Qualls-Corbett 1988, p. 37.

- University of Pennsylvania. "Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary". Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Singh 1997, p. 6.

- Biblical Archaeology Society Staff, Sacred Prostitution in the Story of Judah and Tamar?, 7 August 2018

- Lipiński 2013, pp. 9–27

- Associated with the corresponding verb zanah."Genesis 1:1 (KJV)". Blue Letter Bible. Retrieved 5 April 2018. incorporating Strong's concordance (1890) and Gesenius's Lexicon (1857). Also transliterated qĕdeshah, qedeshah, qědēšā ,qedashah, kadeshah, kadesha, qedesha, kdesha. A modern liturgical pronunciation would be k'deysha.

- "Lexicon results for zanah (Strong's H2181)". Blue Letter Bible. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- "Lexicon results for qĕdeshah (Strong's H6948)". Blue Letter Bible. Retrieved 5 April 2018. incorporating Strong's concordance (1890) and Gesenius's Lexicon (1857).

- Grossman et al 2011, p. 596

- Kamionkowski 2003, pp. 21–22.

- Westenholz 1989, pp. 245–265.

- DeGrado 2018

- Gruber 1986, pp. 133–148.

- Lexicon results for kelev (Strong's H3611), incorporating Strong's Concordance (1890) and Gesenius's Lexicon (1857).

- 2 Kings 22:8

- Sweeney 2001, p. 137.

- 1 Kings 14:24, 1 Kings 15:12 and 2 Kings 23:7

- Deuteronomy 23:17–18

- "NETBible: Oholibah". Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- Strabo. "Geographica". VIII.6.20.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Watson, Andrea (18 October 2016). "It was an ancient form of sex tourism". BBC. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- Stupia, Tiziana. "Salome re-awakens: Beltane at the Temple of Venus in Sicily – Goddess Pages". goddess-pages.co.uk. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- Debord 1982, p. 97.

- Yarshater 1983, p. 107.

- Eusebius, Life of Constantine, 3.55 and 3.58

- "What is child hierodulic servitude?". Anti-Slavery Society. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Melissa Hope Ditmore (2006). Encyclopedia of Prostitution and Sex Work, Volumen 1. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-03-133296-8-5.

- Dunbar 2015.

- Ruspini & Bonifacio 2018.

- Human Rights Watch. Caste: Asia's Hidden Apartheid

- United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. Thirty-seventh session: 15 January – 2 February 2007

- "'Project Combat' launched to eradicate 'Devadasi' system". The Hindu. 30 January 2006. Retrieved 31 January 2007.

- Ways of thinking that connect religion and prostitution

- Kuly 2003, p. 198.

- Greenberg 1988, p. 164.

- Sahagun & Anderson 1982, pp. 55–56.

- Trexler 1995, pp. 132–133.

- Keen1990, p. 97.

- Estrada 2003, pp. 10–14.

- Taylor 1987, p. 87.

- Clendinnen 1991, p. 163.

- Miller & Taube 1993, p. 190.

- Smith 2003, p. 203.

- Guerra 1971, p. 91.

- Flornoy1958, pp. 191–192.

- Williams 1998, p. 320.

- Padilla, Steve (31 August 1989). "Woman Tells Court She Performed Sex Acts for Religious Reasons". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Religion Based On Sex Gets A Judicial Review". The New York Times. 2 May 1990. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- "Star-News – Google News Archive Search". Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- Hunter 2006, p. 419-420.

- Qualls-Corbett 1988, p. 40.

- Qualls-Corbett 1988, p. 43.

- Holland 2008

Bibliography

- Arnaud, Daniel (1973). "La prostitution sacrée en Mésopotamie, un mythe historiographique?". Revue de l'Histoire des Religions (183): 111–115.

- Assante, Julia (2003). "From Whores to Hierodules: the Historiographic Invention of Mesopotamian Female Sex Professionals". In Donohue, A. A.; Fullerton, Mark D. (eds.). Ancient Art and its Historiography. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521815673.

- Baugh, S. M. (September 1999). "Cult Prostitution In New Testament Ephesus: A Reappraisal". Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society. 42 (3): 443–460.

- Budin, Stephanie Lynn (2008). The Myth of Sacred Prostitution in Antiquity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521880909.

- Clendinnen, Inga (1991). Aztecs: An Interpretation. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-40093-7. OCLC 22451031.

- Cooper, Jerrold S. (1971). "Prostitution" (PDF). Reallexikon der Assyriologie. de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110195453.

- Day, John (2004). "Does the Old Testament Refer to Sacred Prostitution and Did it Actually Exist in Ancient Israel?". In McCarthy, Carmel; Healey, John F. (eds.). Biblical & Near Eastern Essays. A&C Black. pp. 2–21. ISBN 9780826466907.

- Debord, Pierre (1982). Aspects Sociaux et économiques de la Vie Religieuse Dans L'Anatolie Gréco-Romaine (in French). BRILL. ISBN 9789004064690.

- DeGrado, Jessie (12 January 2018). "The qdesha in Hosea 4:14: Putting the (Myth of the) Sacred Prostitute to Bed". Vetus Testamentum. 68 (1): 8–40. doi:10.1163/15685330-12341300.

- Dunbar, Julie C. (2015). Women, Music, Culture: An Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 9781351857451.

- Escohotado, Antonio (2018). Rameras y Esposas: Cuatro Mitos Sobre Sexo y Deber (in Spanish). Independently Published. ISBN 9781729289563.

- Estrada, Gabriel S. (2003). "An Aztec Two-Spirit Cosmology: Re-Sounding Nahuatl Masculinities, Elders, Femininities, and Youth". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 24 (2/3): 10–14. doi:10.1353/fro.2004.0008. ISSN 0160-9009. JSTOR 3347344. S2CID 144868230.

- Flornoy, Bertrand (1958). The World of the Inca. Translated by Winifred Bradford. Doubleday.

- Frazer, James George (1914). The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion (3rd ed.). Published in 12 volumes

- Frazer, James George (1922). The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion (abridged ed.).

- Greenberg, David F. (1988). The Construction of Homosexuality. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226306278.

- Grossman, Maxine; et al. (2011). The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199730049.

- Gruber, Mayer (1986). "Hebrew Qedesha and her Canaanite and Akkadian Cognates". Ugarit-Forschungen (18).

- Guerra, Francisco (1971). The Pre-Columbian Mind: A Study Into the Aberrant Nature of Sexual Drives, Drugs Affecting Behaviour and the Attitude Towards Life and Death, with a Survey of Psychotherapy in Pre-Columbian America. Seminar Press Limited. ISBN 9780128410509.

- Herodotus (1920) [c.440 BC]. The Histories of Herodotus. Translated by A. D. Godley. Harvard University Press.

- Henriques, Fernando (1961). Prostitution and society: a survey. MacGibbon & Kee.

- Holland, Eileen (2008). The Wicca Handbook. Weiser Books. ISBN 9781609254520.

isbn:9781609254520.

- Hunter, Jennifer Tibe (2006). "Sacred Prostitution, Contemporary". In Ditmore, Melissa Hope (ed.). Encyclopedia of Prostitution and Sex Work, Volume 2. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-32970-2.

- Ipsen, Avaren (2014). Sex Working and the Bible. Routledge. ISBN 9781317490661.

- Kamionkowski, S. Tamar (2003). Gender Reversal and Cosmic Chaos: A Study in the Book of Ezekiel. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9780567137876.

- Keen, Benjamin (1990). The Aztec Image in Western Thought. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813515724.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1969). The sacred marriage rite; aspects of faith, myth, and ritual in ancient Sumer. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253350350.

- Kuly, Lisa (2003). "Locating Transcendence in Japanese Minzoku Geinô: Yamabushi and Miko Kagura". Ethnologies. 25 (1): 191–208. doi:10.7202/007130ar. ISSN 1481-5974.

- Lipiński, Edward (April 2013). "Cult Prostitution and Passage Rites in the Biblical World" (PDF). The Biblical Annals. 60 (1): 9–27.

- Miller, Mary; Taube, Karl (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya: An Illustrated Dictionary of Mesoamerican Religion. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05068-6. OCLC 27667317.

- Pike, Sarah M. (2004). New Age and Neopagan Religions in America. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231124034.

- Qualls-Corbett, Nancy (1988). The Sacred Prostitute: Eternal Aspect of the Feminine. Inner City Books. ISBN 9780919123311.

pagan.

- Rickard, Kelley (2015). "A Brief Study into Sacred Prostitution in Antiquity". ResearchGate.

- Ruspini, Elisabetta; Bonifacio, Glenda Tibe, eds. (2018). Women and Religion: Contemporary and Future Challenges in the Global Era. Policy Press. ISBN 9781447336372.

- Sahagun, Bernardino De; Anderson, Arthur J. O. (1982). Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain : Introductions and Indices (in Spanish). University of Utah Press. ISBN 9780874801651.

- Singh, Nagendra Kr (1997). Divine Prostitution. APH Publishing. ISBN 9788170248217.

- Smith, Michael E. (2003). The Aztecs (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-23015-7. OCLC 48579073.

- Stol, Marten (2016). "Temple Prostitution". Women in the Ancient Near East. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 9781614512639.

- Sweeney, Marvin Alan (2001). King Josiah of Judah: The Lost Messiah of Israel. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195133240.

- Sweet, R. (1994). "A New Look at the 'Sacred Marriage' in Ancient Mesopotamia". In Robbins, Emmet; Sandahl, Stella (eds.). Corolla Torontonensis : studies in honour of Ronald Morton Smith. TSAR. ISBN 9780920661222.

- Taylor, Clark L (1987). "Legends, Syncretism, and Continuing Echoes of Homosexuality from Pre-Columbian and Colonial Mexico". In Murray, Stephen O. (ed.). Male homosexuality in Central and South America. Instituto Obregón. ISBN 9780942777581.

- Trexler, Richard C. (1995). Sex and conquest: gendered violence, political order, and the European conquest of the Americas. Cornell University Press.

- Westenholz, Joan Goodnick (1989). "Tamar, Qědēšā, Qadištu, and Sacred Prostitution in Mesopotamia". The Harvard Theological Review. 82 (3): 245–265. doi:10.1017/S0017816000016199. ISSN 0017-8160. JSTOR 1510077.

- Williams, Miriam (1998). Heaven's Harlots: My Fifteen Years as a Sacred Prostitute in the Children of God Cult. Eagle Brook. ISBN 9780688155049.

- Yamauchi, Edwin M. (1973). "Cultic Prostitution: a Case Study in Cultural Diffusion". In Hoffner, Harry A. (ed.). Orient and Occident: Essays Presented to Cyrus H. Gordon on the Occasion of His Sixty-fifth Birthday. Butzon & Bercker. ISBN 9783766688057.

- Yarshater, Ehsan (1983). The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521200929.

External links

- Stuckey, H. Johanna. "Sacred Prostitutes". MatriFocus. 2005 vol 5–1.

- Deuteronomy 23:18–19, and a discussion

- Jenin Younes (2008), Sacred Prostitution in Ancient Israel