Salt River (California)

The Salt River is a formerly navigable hanging channel of the Eel River which flowed about 9 miles (14 km) from near Fortuna and Waddington, California, to the estuary at the Pacific Ocean, until siltation from logging and agricultural practices essentially closed the channel. It was historically an important navigation route until the early 20th century. It presently intercepts and drains tributaries from the Wildcat Hills along the south side of the Eel River floodplain. Efforts to restore the river began in 1987, permits and construction began in 2012, and water first flowed in the restored channel in October 2013.

| Salt River | |

|---|---|

The Salt River restoration reopened the lower portion of the river to flow on October 9, 2013. | |

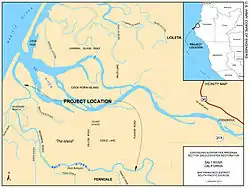

Map of the Salt River | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Humboldt |

| City | Ferndale |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Wildcat Mountains [1] |

| • location | Humboldt County, California |

| • coordinates | 40°32′32.08″N 124°16′58.21″W[1] |

| • elevation | 3 ft (0.91 m)[2] |

| Mouth | Pacific Ocean |

• location | Humboldt County, California |

• coordinates | 40°38′16.46″N 124°18′47.21″W[2] |

• elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Length | 7 mi (11 km)[1] |

| Basin size | 17.03 sq mi (44.1 km2)[3] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Pacific Ocean |

| Basin features | |

| River system | Eel River (California) |

Geology

The California Coast Ranges are relatively young mountain ranges being tectonically uplifted faster than the pace of erosion by several millimeters a year.[4] These rapidly uplifted, unstable slopes produce natural landslides which have filled the channel for tens of thousands of years.[5] Tree stump evidence from the banks near the estuary shows that the area around the mouth of the Eel dropped 11 feet (3.4 m) in the January 26, 1700, Cascadia earthquake.[5] The basin which holds both the Eel and the Salt is underlain by the Eel river syncline, crossed by the Russ and Ferndale faults and affected by the Little Salmon Fault to the north.[6] Both the San Andreas Fault system and the Cascadia Megathrust impact the geomorphology of the basin.[6]

Tributaries

There are five named tributaries which fall from the Wildcat hills and contribute water and sediment to the Salt River.

| Tributary Name | Watershed drainage | Distance of Tributary Mouth to Eel |

|---|---|---|

| Russ Creek | 2,080 acres (840 ha) | 0.8 miles (1.3 km) |

| Smith Creek | 160 acres (65 ha) | 2.1 miles (3.4 km) |

| Reas Creek | 1,210 acres (490 ha) | 3.2 miles (5.1 km) |

| Francis Creek | 1,990 acres (810 ha) | 4.9 miles (7.9 km) |

| Williams Creek | 3,660 acres (1,480 ha) | 7.4 miles (11.9 km) |

Source: United States Department of Agriculture.[3]

Ecology

Four species of anadromous salmonids, the coho salmon, chinook salmon, rainbow trout and coastal cutthroat trout are known from the estuary of the Salt River as are about two dozen estuarine fish including herring, sardine, smelt, stickleback, perch, sculpin, sole and flounder, and the freshwater invasive Sacramento pikeminnow.[6]:37

History

Prehistory

A Wiyot village named Wotwetwok was situated opposite the mouth of Francis Creek (Topochochwil in Wiyot) along the Salt River, which they called Oka't.[7] The families of this village hunted, fished and used the river and the delta for navigation for thousands of years.[7] At that time, the Salt River delta was shaded by Sitka spruce and Alder, shadowing ferns and brush.[8]

Further upstream coast redwoods became part of the canopy. Early writers described a series of prairies surrounded by fir and redwood with ferns, grasses and wildflowers. One said it was "dazzling even to remember."[7] Others pointed out that the land was prone to flooding, and that the fern prairies were not easy to convert to agricultural lands.[7] Game including California mule deer, Roosevelt elk, bear, ducks, geese, brandt, cranes, and other waterfowl were common.[7]

Salmon and other anadromous fish used the Salt River to get to tributaries in the Wildcat Hills where they spawned, and juveniles later matured before swimming downstream to the estuary and returning to the sea.[9]

Recorded history

The first westerner to enter the Eel River was Sebastián Vizcaíno, sailing on behalf of Philip III of Spain, seeking a mythical northwest passage described in secret papers as being at the latitude of Cape Mendocino. He sailed into the mouth of the Eel in January 1603 where instead of the cultured city of Quivera the papers had described, he encountered native people they described as "uncultured."[10]:170–171

The first American vessel to arrive in the Salt River was the Jacob M. Ryerson, which crossed the offshore bar on April 3, 1850, and moved up the Salt River the following day, recording a draft of 11 feet (3.4 m).[7] In 1851, the tide turnaround point was 14 miles (23 km) upstream of the mouth of the Eel with brackish water rising to 4 miles (6.4 km) from the mouth of the Eel River which was about 120 feet (37 m) wide.[7] By the middle 1870s, 175-foot-long (53 m) steamships sailed 2.5 miles (4.0 km) up the Salt River to the town of Port Kenyon, where the channel was approximately 200 feet (61 m) wide.[6]:28 The low water depth was 13 feet (4.0 m),[5] and mean high tide was 18 feet (5.5 m).[6]:28 The island formed between the Salt River and the main course of the Eel, shown on old maps of Port Kenyon and the Eel River bottoms, was variously named "the Eel River Island" or "The Island."[7] Even with the wide and deep channel, siltation and annual flooding soon resulted in the loss of business and residents from Port Kenyon to Ferndale and Arlynda Corners.[11]

Shipping

In December 1877, the steamer Continental, which had been making regular trips in and out of Port Kenyon, suffered a steam explosion, wrecked and beached 2 miles (3.2 km) from the entrance of the Eel.[7][12] After the Continental wrecked, two other steamers, the George Harley and the Alexander Duncan[13] began shipping from Port Kenyon to San Francisco and Eureka.[7] In June 1878, the Alexander Duncan wrecked on the south spit in the Eel River estuary.[12] From 1878 to 1880, the 136-foot-long (41 m) Thomas A. Whitelaw, which was built specifically for Eel River trade, carried 400 tons of cargo with a draft of 13 feet (4.0 m)[12] as well as 46 passengers.[7] By 1881, a locally constructed vessel, the Ferndale, had taken up the Port Kenyon to San Francisco route, and the 65 feet (20 m) paddle-wheel steamer Edith provided transport to the upper reaches of the Eel and Port Kenyon.[7] Shifting sand bars at the mouth of the Eel stopped the Port Kenyon to San Francisco run in 1884 when both the Ferndale and the Edith were lost, leaving the sawmill at Port Kenyon with no transportation for its product.[7] In 1885, the steamer Mary D. Hume was put on the route; even with steam power she had to wait for two weeks to cross the Eel River bar, which resulted in a movement to dredge the mouth of the river. In eleven months of service without an assisting tug, the Mary D. Hume moved 900 passengers and $500,000 worth of goods.[7] In summer 1887, the tugboat Robarts was added to assist ships at the bar, but within two years the Robarts was at work in San Francisco instead.[7] In 1890, despite yet another steamer on the route, the mouth of the Salt River began to shoal.[7] In 1893, the steamer Weeott,[14] with electric lights and substantial passenger amenities, began service carrying butter, eggs, lumber, shakes, shingles, apples, salmon, potatoes, oats, peas, lentils, barley, wool, and other products.[7] The Weeott wrecked on the south jetty of Humboldt Bay on December 1, 1899 with two fatalities.[15] In 1902 the Argo was placed in service; she carried passengers and produce until 1908 when shipping on the Salt River effectively ended.[7] The need for Port Kenyon for shipping declined even before construction of Fernbridge in 1911 and the Eel River Railroad in 1914 rendered it unnecessary.[7] Part of the reason for this decline was that human efforts were recognizably silting in the Salt River. In 1866, Uri Williams one of the 1852 pioneer settlers noted that the overall water depth was less than it had been in the earliest days, and he attributed this to the clearing of the country, constant cultivation and stock ranging, all of which had created wash and sediment which was ending up in the rivers.[7]

Commercial fishing

Commercial fish canning began in 1877 and used the Salt River to ship out ten to twelve thousand 1 pound (0.45 kg)-pound cans of salmon a day, each prepared by controversial Chinese workers.[7] By 1892, the cannery closed due to a lack of fish.[7] By 1892 production at the Port Kenyon sawmill had increased tenfold in five years, with more than 300,000 feet (91,000 m) of locally cut spruce logs.[7] In 1897, a fish hatchery on Price Creek was hatching 4,000,000 salmon eggs from Sacramento stock, and was the second largest hatchery in the state; it operated until 1916.[7] In 1906 the Tallant-Grant Company built a new cannery in the Port Kenyon Cold Storage Company building and imported 20 Chinese laborers, several Japanese and a few Russian women from Astoria, Oregon to whom the Ferndale Chamber of Commerce had no objection prior to or after their arrival.[7] Residents from other towns threatened mob action, and the Chinese were protected by law enforcement and moved to an old cookhouse on Indian Island until they could be removed by boat.[7]

Reclamation

The Salt River Reclamation District was formed in 1884 to convert the sloughs and salt marshes to agricultural land.[6]:13 Four years later a U.S. Coast and Geodetic surveyor pointed out that the dikes and blocked sloughs were silting up and reducing the tidal area of the Salt River delta.[6]:13

In 1897 a lawsuit was filed between the owner of the Port Kenyon lumber mill and the owner of acreage in the tidelands near what is now Riverside Ranch because reclamation work had caused the delta to fill with sediment and reduce the draft available for shipping at Port Kenyon.[7] In 1898, a judge ruled in favor of the ranchers of the Russ Company, stating that the sloughs they had closed were never navigable and that the state had granted the right of reclamation regardless of the problems it might cause for the Eel River.[7] The case was ultimately ruled on by the California Supreme Court in 1901.[6]

Salt River bridge

During the 1880s, people and materials crossed the Salt River on a log pontoon bridge located at the site of the current Dillon Road bridge.40°35′42.02″N 124°16′29.09″W During floods, one end would be let loose while one end remained tethered. The bridge would be tied back up when the flood was over. Even so, the bridge needed constant rebuilding. In 1886, the first bridge intended to be permanent was built by the American Bridge Company, but it was destroyed in 1890, and replaced in 1893. That second "permanent" bridge was destroyed in the flood of 1894. The third bridge was built in 1894 with extra clearance, and was of a style called Howe pony truss timber bridge. It survived both a flood and the 1906 San Francisco earthquake[8]:1 when Port Kenyon subsided several feet.[6]

The Valley Flower Creamery was built in 1914 north of the Salt River on Dillon Road, expanded operations over the next several years, and continued in business for 45 years.[8]:3 In its earliest days, the creamery was producing about 75,000 pounds (34,000 kg) pounds of butter and 37,000 pounds (17,000 kg) pounds of casein every month, and during World War I they had a contract with the U.S. Navy for 150,000 pounds (68,000 kg) of butter.[8]:3

_1994bridge.jpg.webp)

Because all their produce had to cross Salt River on the aging timber bridge, the county replaced it in 1919 with a 142 feet (43 m) reinforced concrete girder bridge, which when built was the world's longest bridge of that type, with spans nearly double the length of the prior record holder.[8]:1–3[16] The bridge became eligible for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places in 1987,[8]:2 but was torn down and replaced by a concrete beam bridge in 1994.[17]

Siltation

Historical land reclamation activities for agriculture, including tide gates and levees as well as siltation from uphill landslides and erosion, slowly filled in the river over time, reducing the watershed by 42 percent.[9] Most of the original vegetation and trees were gone by 1900, leading to an increase in siltation and a shallowing of the river. In the ten years spanning 1889 to 1899, the river depth changed from 20 feet (6.1 m) to 2 feet (0.61 m).[8]:1 Logging in the Wildcat hills continued and intensified following World War II, leading to construction of logging roads and exposed slopes, producing additional siltation.[6] Siltation continued; by 1949, the Salt River had become so shallow that "at low tide... parts of it can be waded across by a man with hip boots."[7] After the catastrophic 1964 flood, nearly 13,000 acres (5,300 ha) had been covered by sand or silt.[6] In 1967, residents built a levee cutting off the flow of water from the Eel into the Salt,[6]:17 which prevents the Eel River from spilling over into the Salt channel during high water, and facilitating sediment removal.[5] Without the occasional overflow from the Eel, plus the 1964 sediments, and the addition of landslide sediments from the 1992 Cape Mendocino earthquakes,[6] by 2008 the river had become mostly dry land.[7] During the 1970s, the California Department of Fish and Game stopped farmers from clearing out local channels; willows and brush quickly filled in the riverbed,[6] and caught sediment, stopping nearly all the flow in the lower half of the Salt, leading to flooding, problems with dilution ratios at the Ferndale Water Treatment Plant, and water quality in general.[9]

Besides all the other changes, the Eel itself carries less water than in years past, due to the construction of the Pillsbury Dam and the Potter Valley Project, which divert 95 percent of the summer flow to Sonoma County, reducing the length of the stream by 120 miles (190 km) above the dams.[5]

Restoration

Following the near-total siltation of the river and annual winter flooding, the Eel River Conservation District was formed in 1987 with the goal of reopening the Salt River.[6]:32 Working with the United States Department of Agriculture, they applied for and were denied United States Army Corps of Engineers funding in 1989.[6]:32 The Eel River Conservation District was expanded to become the Humboldt County Resource Conservation District in 1993. Vegetation was cleared from the Salt River channel by the California Conservation Corps in 1996. The following year the Federal Endangered Species Act listed the coho salmon as endangered, chinook salmon were listed as threatened in 1999, and in 2000 steelhead were added to the Federal threatened species list, which made habitat restoration of the Salt a priority.[6]:33

Tributary Francis Creek was rebuilt in 2002, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began work on Salt River studies under the aquatic ecosystem restoration program. In 2004 a stakeholders' group was formed, and all U.S. Army Corps funding was eliminated.[6]:33 Over the next two years, stakeholders obtained $6,169,502 in Proposition 50 funds to begin implementation of the Salt River Ecosystem Restoration Project.[18] The Salt River Watershed Council was formed in 2007 and incorporated as a non-profit the following year to maintain the long-term aspects of the project.[18][19]

The Salt River restoration project received its final permit in September 2012[18] to restore the Salt to hydraulic function by means of channel restoration, restoration of the 444 acres (180 ha) Riverside Ranch, upstream sediment reduction efforts, and long-term management.[9] Agencies involved in the 26-year process of Salt River restoration include the City of Ferndale, County of Humboldt, North Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board, California Coastal Conservancy, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, California State Lands Commission, California Coastal Commission, California State Historic Preservation Office, National Marine Fisheries Service, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.[20] Construction on Phase I of the project began May 2013,[18] and the estuary was connected to the newly excavated channel by removal of a cofferdam on October 9, 2013.[21]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Salt River (California). |

References

- Salt River Restoration, Sec 206 , U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, May 1, 2013, accessed October 20, 2013

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Salt River

- United States. Soil Conservation Service; Eel River Resource Conservation District (Calif.) (1993). Salt River Watershed Local Implementation Plan, Humboldt County, California. USDA Soil Conservation Service.

- Gendaszek, Andrew S.; Greg Balco; David R. Montgomery; John O. H. Stone; Nathaniel Thompson (2006). Long-term Erosion Rates and Styles of Erosion in the Coastal Ranges of the Pacific Northwest (PDF). Seattle, Washington: Quaternary Research Center and Department of Earth & Space Sciences, University of Washington.

- Hight, Jim (16 September 2004). "Lost Rivers and Ghost Towns". North Coast Journal. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- "Salt River Basin Assessment Report". Coastal Watershed Planning and Assessment Program. California Department of Fish and Game. May 2005. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- Roscoe, James; Erik Whiteman; Jennifer Burns; William Rich; Jerry Rohde; Suzie Van Kirk (March 2008). A Cultural Resources Investigation of the Salt River Ecosystem Restoration Project Located near Ferndale, Humboldt County, California (PDF). Bayside, California: Roscoe and Associates Cultural Resources Consultants. p. 89.

- :1"Salt River Bridge, Number CA-126" (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record. Library of Congress. 1992. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 21, 2013. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- Grassetti Environmental Consulting; California State Coastal Conservancy; Kamman Hydrology and Engineering, Inc (February 2011). Final environmental impact report: Salt River Ecosystem Restoration Project SCH# SD2007-05-6 (PDF). Eureka, California: Humboldt County Resource Conservation District.

- Philip L. Fradkin (1995). The Seven States of California: A Natural and Human History. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20942-8.

- Carlson, Beverly, editor; Ferndale Union High School; class of 1977 (1977). Where the ferns grew tall: An early history of Ferndale. Ferndale, California: Ferndale Union High School. p. 379. 0-7385-2890-0.

- Dennis M. Powers (January 7, 2009). Taking the Sea: Perilous Waters, Sunken Ships, and the True Story of the Legendary Wrecker Captains. AMACOM Div American Mgmt Assn. pp. 46–. ISBN 978-0-8144-1354-8.

- Blethen Levy, D.A. (2013). "Steamer Alexander Duncan". World Seaport History. The Maritime Heritage Project. Archived from the original on October 23, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- Gleanings in Bee Culture. A. I. Root Co. 1895. pp. 554–.

- Life-saving Service (1901). Annual Report of the Operations of the United States Life-saving Service. pp. 31–.

- "Salt River Bridge, Spanning Salt River at Dillon Road, Ferndale, Humboldt County, CA". Online Catalog of Prints and Photographs. Library of Congress. 2013. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

1920 photo at http://lcweb2.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/ca/ca1700/ca1725/photos/011189pr.jpg

- "Dillon Road at Salt River". California, FIPS 023, NBI# 04C0012. National Bridge Inventory Database Search. 2013. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- Salt River Ecosystem Restoration Project: A Short History (PDF). Humboldt County Resource Conservation District. 2012.

- "Homepage". Salt River Watershed Council (SRWC). 2013. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- Bowen, Michael (May 24, 2007). Riverside Ranch Acquisition, Coastal Conservancy Staff Recommendation, File No. 07-006 (PDF). California Coastal Conservancy. pp. 1–8.

- "Information and Updates" (PDF). Salt River Restoration Ecosystem Project. Humboldt County Resource Conservation District. October 16, 2013. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

Further reading

- Burdette Adrian Ogle (January 2010). Geology of Eel River Valley Area, Humboldt County, California. General Books LLC. ISBN 978-1-153-48183-0.

- Salt River Watershed Review Report, November 1987, USDA Soil Conservation Service. 1987. Pages 1–9.