Saturated fat

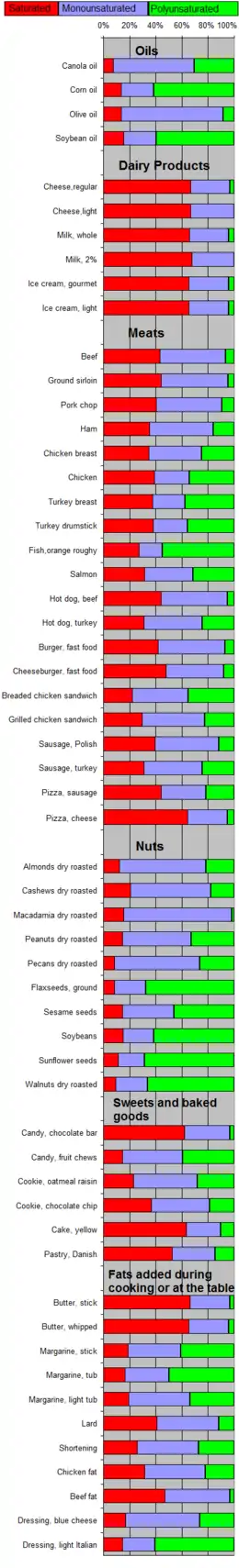

| Types of fats in food |

|---|

| See also |

A saturated fat is a type of fat in which the fatty acid chains have all or predominantly single bonds. A fat is made of two kinds of smaller molecules: glycerol and fatty acids. Fats are made of long chains of carbon (C) atoms. Some carbon atoms are linked by single bonds (-C-C-) and others are linked by double bonds (-C=C-).[1] Double bonds can react with hydrogen to form single bonds. They are called saturated because the second bond is broken and each half of the bond is attached to (saturated with) a hydrogen atom.

Saturated fats tend to have higher melting points than their corresponding unsaturated fats, leading to the popular understanding that saturated fats tend to be solids at room temperatures, while unsaturated fats tend to be liquid at room temperature with varying degrees of viscosity.

Most animal fats are saturated. The fats of plants and fish are generally unsaturated.[1] Various foods contain different proportions of saturated and unsaturated fat. Many processed foods like foods deep-fried in hydrogenated oil and sausage are high in saturated fat content. Some store-bought baked goods are as well, especially those containing partially hydrogenated oils.[2][3][4] Other examples of foods containing a high proportion of saturated fat and dietary cholesterol include animal fat products such as lard or schmaltz, fatty meats and dairy products made with whole or reduced fat milk like yogurt, ice cream, cheese and butter.[5] Certain vegetable products have high saturated fat content, such as coconut oil and palm kernel oil.[6]

Guidelines released by many medical organizations, including the World Health Organization, have advocated for reduction in the intake of saturated fat to promote health and reduce the risk from cardiovascular diseases. Many review articles also recommend a diet low in saturated fat and argue it will lower risks of cardiovascular diseases,[7] diabetes, or death.[8]

Fat profiles

While nutrition labels regularly combine them, the saturated fatty acids appear in different proportions among food groups. Lauric and myristic acids are most commonly found in "tropical" oils (e.g., palm kernel, coconut) and dairy products. The saturated fat in meat, eggs, cacao, and nuts is primarily the triglycerides of palmitic and stearic acids.

| Food | Lauric acid | Myristic acid | Palmitic acid | Stearic acid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coconut oil | 47% | 18% | 9% | 3% |

| Palm kernel oil | 48% | 1% | 44% | 5% |

| Butter | 3% | 11% | 29% | 13% |

| Ground beef | 0% | 4% | 26% | 15% |

| Salmon | 0% | 1% | 29% | 3% |

| Egg yolks | 0% | 0.3% | 27% | 10% |

| Cashews | 2% | 1% | 10% | 7% |

| Soybean oil | 0% | 0% | 11% | 4% |

| Cocoa butter[10] | 1% | 0–4% | 24.5–33.7% | 33.7–40.2% |

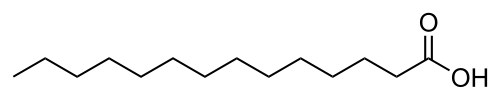

Examples of saturated fatty acids

Some common examples of fatty acids:

- Butyric acid with 4 carbon atoms (contained in butter)

- Lauric acid with 12 carbon atoms (contained in coconut oil, palm kernel oil, and breast milk)

- Myristic acid with 14 carbon atoms (contained in cow's milk and dairy products)

- Palmitic acid with 16 carbon atoms (contained in palm oil and meat)

- Stearic acid with 18 carbon atoms (also contained in meat and cocoa butter)

| Food | Saturated | Mono- unsaturated | Poly- unsaturated |

|---|---|---|---|

| As weight percent (%) of total fat | |||

| Cooking oils | |||

| Algal oil[11] | 04 | 92 | 04 |

| Canola[12] | 08 | 64 | 28 |

| Coconut oil | 87 | 13 | 00 |

| Corn oil | 13 | 24 | 59 |

| Cottonseed oil[12] | 27 | 19 | 54 |

| Olive oil[13] | 14 | 73 | 11 |

| Palm kernel oil[12] | 86 | 12 | 02 |

| Palm oil[12] | 51 | 39 | 10 |

| Peanut oil[14] | 17 | 46 | 32 |

| Rice bran oil | 25 | 38 | 37 |

| Safflower oil, high oleic[15] | 06 | 75 | 14 |

| Safflower oil, linoleic[12][16] | 06 | 14 | 75 |

| Soybean oil | 15 | 24 | 58 |

| Sunflower oil[17] | 11 | 20 | 69 |

| Mustard oil | 11 | 59 | 21 |

| Dairy products | |||

| Butterfat[12] | 66 | 30 | 04 |

| Cheese, regular | 64 | 29 | 03 |

| Cheese, light | 60 | 30 | 00 |

| Ice cream, gourmet | 62 | 29 | 04 |

| Ice cream, light | 62 | 29 | 04 |

| Milk, whole | 62 | 28 | 04 |

| Milk, 2% | 62 | 30 | 00 |

| *Whipping cream[18] | 66 | 26 | 05 |

| Meats | |||

| Beef | 33 | 38 | 05 |

| Ground sirloin | 38 | 44 | 04 |

| Pork chop | 35 | 44 | 08 |

| Ham | 35 | 49 | 16 |

| Chicken breast | 29 | 34 | 21 |

| Chicken | 34 | 23 | 30 |

| Turkey breast | 30 | 20 | 30 |

| Turkey drumstick | 32 | 22 | 30 |

| Fish, orange roughy | 23 | 15 | 46 |

| Salmon | 28 | 33 | 28 |

| Hot dog, beef | 42 | 48 | 05 |

| Hot dog, turkey | 28 | 40 | 22 |

| Burger, fast food | 36 | 44 | 06 |

| Cheeseburger, fast food | 43 | 40 | 07 |

| Breaded chicken sandwich | 20 | 39 | 32 |

| Grilled chicken sandwich | 26 | 42 | 20 |

| Sausage, Polish | 37 | 46 | 11 |

| Sausage, turkey | 28 | 40 | 22 |

| Pizza, sausage | 41 | 32 | 20 |

| Pizza, cheese | 60 | 28 | 05 |

| Nuts | |||

| Almonds dry roasted | 09 | 65 | 21 |

| Cashews dry roasted | 20 | 59 | 17 |

| Macadamia dry roasted | 15 | 79 | 02 |

| Peanut dry roasted | 14 | 50 | 31 |

| Pecans dry roasted | 08 | 62 | 25 |

| Flaxseeds, ground | 08 | 23 | 65 |

| Sesame seeds | 14 | 38 | 44 |

| Soybeans | 14 | 22 | 57 |

| Sunflower seeds | 11 | 19 | 66 |

| Walnuts dry roasted | 09 | 23 | 63 |

| Sweets and baked goods | |||

| Candy, chocolate bar | 59 | 33 | 03 |

| Candy, fruit chews | 14 | 44 | 38 |

| Cookie, oatmeal raisin | 22 | 47 | 27 |

| Cookie, chocolate chip | 35 | 42 | 18 |

| Cake, yellow | 60 | 25 | 10 |

| Pastry, Danish | 50 | 31 | 14 |

| Fats added during cooking or at the table | |||

| Butter, stick | 63 | 29 | 03 |

| Butter, whipped | 62 | 29 | 04 |

| Margarine, stick | 18 | 39 | 39 |

| Margarine, tub | 16 | 33 | 49 |

| Margarine, light tub | 19 | 46 | 33 |

| Lard | 39 | 45 | 11 |

| Shortening | 25 | 45 | 26 |

| Chicken fat | 30 | 45 | 21 |

| Beef fat | 41 | 43 | 03 |

| Goose fat[19] | 33 | 55 | 11 |

| Dressing, blue cheese | 16 | 54 | 25 |

| Dressing, light Italian | 14 | 24 | 58 |

| Other | |||

| Egg yolk fat[20] | 36 | 44 | 16 |

| Avocado[21] | 16 | 71 | 13 |

| Unless else specified in boxes, then reference is:[22] | |||

| * 3% is trans fats | |||

Association with diseases

Cardiovascular disease

The effect of saturated fat on heart disease has been extensively studied.[23] There are strong, consistent, and graded relationships between saturated fat intake, blood cholesterol levels, and the epidemic of cardiovascular disease.[8] The relationships are accepted as causal.[24][25]

Many health authorities such as the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics,[26] the British Dietetic Association,[27] American Heart Association,[8] the World Heart Federation,[28] the British National Health Service,[29] among others,[30][31] advise that saturated fat is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. The World Health Organization in May 2015 recommends switching from saturated to unsaturated fats.[32]

There is moderate-quality evidence that reducing the proportion of saturated fat in the diet, and replacing it with unsaturated fats or carbohydrates over a period of at least two years, leads to a reduction in the risk of cardiovascular disease.[23]

Dyslipidemia

The consumption of saturated fat is generally considered a risk factor for dyslipidemia, which in turn is a risk factor for some types of cardiovascular disease.[33][34][35][36][37]

Abnormal blood lipid levels, that is high total cholesterol, high levels of triglycerides, high levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL, "bad" cholesterol) or low levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL, "good" cholesterol) cholesterol are all associated with increased risk of heart disease and stroke.[28]

Meta-analyses have found a significant relationship between saturated fat and serum cholesterol levels.[8][38] High total cholesterol levels, which may be caused by many factors, are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.[39][40] However, other indicators measuring cholesterol such as high total/HDL cholesterol ratio are more predictive than total serum cholesterol.[40] In a study of myocardial infarction in 52 countries, the ApoB/ApoA1 (related to LDL and HDL, respectively) ratio was the strongest predictor of CVD among all risk factors.[41] There are other pathways involving obesity, triglyceride levels, insulin sensitivity, endothelial function, and thrombogenicity, among others, that play a role in CVD, although it seems, in the absence of an adverse blood lipid profile, the other known risk factors have only a weak atherogenic effect.[42] Different saturated fatty acids have differing effects on various lipid levels.[43]

Breast cancer

A meta-analysis published in 2003 found a significant positive relationship in both control and cohort studies between saturated fat and breast cancer.[44] However two subsequent reviews have found weak or insignificant associations of saturated fat intake and breast cancer risk,[45][46] and note the prevalence of confounding factors.[45][47]

Colorectal cancer

One review found limited evidence for a positive relationship between consuming animal fat and incidence of colorectal cancer.[48]

Ovarian cancer

Meta-analyses of clinical studies found evidence for increased risk of ovarian cancer by high consumption of saturated fat.[49]

Prostate cancer

Some researchers have indicated that serum myristic acid[50][51] and palmitic acid[51] and dietary myristic[52] and palmitic[52] saturated fatty acids and serum palmitic combined with alpha-tocopherol supplementation[50] are associated with increased risk of prostate cancer in a dose-dependent manner. These associations may, however, reflect differences in intake or metabolism of these fatty acids between the precancer cases and controls, rather than being an actual cause.[51]

Bones

Mounting evidence indicates that the amount and type of fat in the diet can have important effects on bone health. Most of this evidence is derived from animal studies. The data from one study indicated that bone mineral density is negatively associated with saturated fat intake and that men may be particularly vulnerable.[53]

Dietary recommendations

Recommendations to reduce or limit dietary intake of saturated fats are made by the World Health Organization,[54] American Heart Association,[8] Health Canada,[55] the US Department of Health and Human Services,[56] the UK National Health Service,[57] the Australian Department of Health and Aging,[58] the Singapore Ministry of Health,[59] the Indian Ministry of Health and Family Welfare,[60] the New Zealand Ministry of Health,[61] and Hong Kong's Department of Health.[62]

In 2003, the World Health Organization (WHO) and Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) expert consultation report concluded that "intake of saturated fatty acids is directly related to cardiovascular risk.[63] The traditional target is to restrict the intake of saturated fatty acids to less than 10% of daily energy intake and less than 7% for high-risk groups. If populations are consuming less than 10%, they should not increase that level of intake. Within these limits, the intake of foods rich in myristic and palmitic acids should be replaced by fats with a lower content of these particular fatty acids. In developing countries, however, where energy intake for some population groups may be inadequate, energy expenditure is high and body fat stores are low (BMI <18.5 kg/m2). The amount and quality of fat supply have to be considered keeping in mind the need to meet energy requirements. Specific sources of saturated fat, such as coconut and palm oil, provide low-cost energy and may be an important source of energy for the poor."[63]

A 2004 statement released by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) determined that "Americans need to continue working to reduce saturated fat intake…"[64] In addition, reviews by the American Heart Association led the Association to recommend reducing saturated fat intake to less than 7% of total calories according to its 2006 recommendations.[65][66] This concurs with similar conclusions made by the US Department of Health and Human Services, which determined that reduction in saturated fat consumption would positively affect health and reduce the prevalence of heart disease.[67]

The United Kingdom, National Health Service claims the majority of British people eat too much saturated fat. The British Heart Foundation also advises people to cut down on saturated fat. People are advised to cut down on saturated fat and read labels on the food they buy.[68][69]

A 2004 review stated that "no lower safe limit of specific saturated fatty acid intakes has been identified" and recommended that the influence of varying saturated fatty acid intakes against a background of different individual lifestyles and genetic backgrounds should be the focus in future studies.[70]

Blanket recommendations to lower saturated fat were criticized at a 2010 conference debate of the American Dietetic Association for focusing too narrowly on reducing saturated fats rather than emphasizing increased consumption of healthy fats and unrefined carbohydrates. Concern was expressed over the health risks of replacing saturated fats in the diet with refined carbohydrates, which carry a high risk of obesity and heart disease, particularly at the expense of polyunsaturated fats which may have health benefits. None of the panelists recommended heavy consumption of saturated fats, emphasizing instead the importance of overall dietary quality to cardiovascular health.[71]

In a 2017 comprehensive review of the literature and clinical trials, the American Heart Association published a recommendation that saturated fat intake be reduced or replaced by products containing monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, a dietary adjustment that could reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases by 30%.[8]

Molecular description

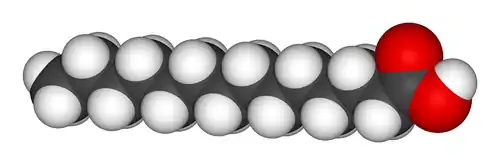

The two-dimensional illustration has implicit hydrogen atoms bonded to each of the carbon atoms in the polycarbon tail of the myristic acid molecule (there are 13 carbon atoms in the tail; 14 carbon atoms in the entire molecule).

Carbon atoms are also implicitly drawn, as they are portrayed as intersections between two straight lines. "Saturated," in general, refers to a maximum number of hydrogen atoms bonded to each carbon of the polycarbon tail as allowed by the Octet Rule. This also means that only single bonds (sigma bonds) will be present between adjacent carbon atoms of the tail.

See also

References

- Reece, Jane; Campbell, Neil (2002). Biology. San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-0-8053-6624-2.

- "Saturated fats". American Heart Association. 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- "Top food sources of saturated fat in the US". Harvard University School of Public Health. 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- "Saturated, Unsaturated, and Trans Fats". choosemyplate.gov. 2020.

- "Saturated Fat". American Heart Association. 2020.

- "What are "oils"?". ChooseMyPlate.gov, US Department of Agriculture. 2015. Archived from the original on 9 June 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- Hooper L, Martin N, Abdelhamid A, Davey Smith G (June 2015). "Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD011737. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011737. PMID 26068959.

- Sacks FM, Lichtenstein AH, Wu JH, Appel LJ, Creager MA, Kris-Etherton PM, Miller M, Rimm EB, Rudel LL, Robinson JG, Stone NJ, Van Horn LV (July 2017). "Dietary Fats and Cardiovascular Disease: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 136 (3): e1–e23. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000510. PMID 28620111. S2CID 367602.

- "USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 20". United States Department of Agriculture. 2007. Archived from the original on 2016-04-14.

- Kumar, Vijay (Jan 2014). "Cocoa Butter and its Alternatives". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Thrive Culinary Algae Oil". Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- Anderson D. "Fatty acid composition of fats and oils" (PDF). Colorado Springs: University of Colorado, Department of Chemistry. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- "NDL/FNIC Food Composition Database Home Page". United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- "Basic Report: 04042, Oil, peanut, salad or cooking". USDA. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- "Oil, vegetable safflower, oleic". nutritiondata.com. Condé Nast. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- "Oil, vegetable safflower, linoleic". nutritiondata.com. Condé Nast. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- "Oil, vegetable, sunflower". nutritiondata.com. Condé Nast. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- USDA Basic Report Cream, fluid, heavy whipping

- "Nutrition And Health". The Goose Fat Information Service.

- "Egg, yolk, raw, fresh". nutritiondata.com. Condé Nast. Retrieved 24 August 2009.

- "09038, Avocados, raw, California". National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 26. United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- "Feinberg School > Nutrition > Nutrition Fact Sheet: Lipids". Northwestern University. Archived from the original on 2011-07-20.

- Hooper, Lee; Martin, Nicole; Jimoh, Oluseyi F.; Kirk, Christian; Foster, Eve; Abdelhamid, Asmaa S. (21 August 2020). "Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8: CD011737. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011737.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 32827219.

- Graham I, Atar D, Borch-Johnsen K, Boysen G, Burell G, Cifkova R, et al. (2007). "European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: executive summary". European Heart Journal. 28 (19): 2375–2414. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehm316. PMID 17726041.

- Labarthe D (2011). "Chapter 17 What Causes Cardiovascular Diseases?". Epidemiology and prevention of cardiovascular disease: a global challenge (2nd ed.). Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7637-4689-6.

- Kris-Etherton PM, Innis S (September 2007). "Position of the American Dietetic Association and Dietitians of Canada: Dietary Fatty Acids". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 107 (9): 1599–1611 [1603]. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.024. PMID 17936958.

- "Food Fact Sheet - Cholesterol" (PDF). British Dietetic Association. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- "Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors". World Heart Federation. 30 May 2017. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- "Lower your cholesterol". National Health Service. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- "Nutrition Facts at a Glance - Nutrients: Saturated Fat". Food and Drug Administration. 2009-12-22. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- "Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for fats, including saturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, trans fatty acids, and cholesterol". European Food Safety Authority. 2010-03-25. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- "Healthy diet Fact sheet N°394". May 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- Faculty of Public Health of the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the United Kingdom. Position Statement on Fat [Retrieved 2011-01-25].

- Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation (2003). "Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- "Cholesterol". Irish Heart Foundation. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (December 2010). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010 (PDF) (7th ed.). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Cannon C, O'Gara P (2007). Critical Pathways in Cardiovascular Medicine (2nd ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 243.

- Clarke R, Frost C, Collins R, Appleby P, Peto R (1997). "Dietary lipids and blood cholesterol: quantitative meta-analysis of metabolic ward studies". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 314 (7074): 112–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.314.7074.112. PMC 2125600. PMID 9006469.

- Bucher HC, Griffith LE, Guyatt GH (February 1999). "Systematic review on the risk and benefit of different cholesterol-lowering interventions". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 19 (2): 187–195. doi:10.1161/01.atv.19.2.187. PMID 9974397.

- Lewington S, Whitlock G, Clarke R, Sherliker P, Emberson J, Halsey J, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R (December 2007). "Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths". Lancet. 370 (9602): 1829–39. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61778-4. PMID 18061058. S2CID 54293528.

- Labarthe D (2011). "Chapter 11 Adverse Blood Lipid Profile". Epidemiology and prevention of cardiovascular disease: a global challenge (2 ed.). Jones and Bartlett Publishers. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-7637-4689-6.

- Labarthe D (2011). "Chapter 11 Adverse Blood Lipid Profile". Epidemiology and prevention of cardiovascular disease: a global challenge (2nd ed.). Jones and Bartlett Publishers. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-7637-4689-6.

- Thijssen MA, Mensink RP (2005). "Fatty acids and atherosclerotic risk". Atherosclerosis: Diet and Drugs. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 170. Springer. pp. 165–94. doi:10.1007/3-540-27661-0_5. ISBN 978-3-540-22569-0. PMID 16596799.

- Boyd NF, Stone J, Vogt KN, Connelly BS, Martin LJ, Minkin S (November 2003). "Dietary fat and breast cancer risk revisited: a meta-analysis of the published literature". British Journal of Cancer. 89 (9): 1672–1685. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601314. PMC 2394401. PMID 14583769.

- Hanf V, Gonder U (2005-12-01). "Nutrition and primary prevention of breast cancer: foods, nutrients and breast cancer risk". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 123 (2): 139–149. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.05.011. PMID 16316809.

- Lof M, Weiderpass E (February 2009). "Impact of diet on breast cancer risk". Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 21 (1): 80–85. doi:10.1097/GCO.0b013e32831d7f22. PMID 19125007. S2CID 9513690.

- Freedman LS, Kipnis V, Schatzkin A, Potischman N (Mar–Apr 2008). "Methods of Epidemiology: Evaluating the Fat–Breast Cancer Hypothesis – Comparing Dietary Instruments and Other Developments". Cancer Journal (Sudbury, Mass.). 14 (2): 69–74. doi:10.1097/PPO.0b013e31816a5e02. PMC 2496993. PMID 18391610.

- Lin OS (2009). "Acquired risk factors for colorectal cancer". Cancer Epidemiology. Methods in Molecular Biology. 472. pp. 361–72. doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-492-0_16. ISBN 978-1-60327-491-3. PMID 19107442.

- Huncharek M, Kupelnick B (2001). "Dietary fat intake and risk of epithelial ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis of 6,689 subjects from 8 observational studies". Nutrition and Cancer. 40 (2): 87–91. doi:10.1207/S15327914NC402_2. PMID 11962260. S2CID 24890525.

- Männistö S, Pietinen P, Virtanen MJ, Salminen I, Albanes D, Giovannucci E, Virtamo J (December 2003). "Fatty acids and risk of prostate cancer in a nested case-control study in male smokers". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 12 (12): 1422–8. PMID 14693732.

- Crowe FL, Allen NE, Appleby PN, Overvad K, Aardestrup IV, Johnsen NF, Tjønneland A, Linseisen J, Kaaks R, Boeing H, Kröger J, Trichopoulou A, Zavitsanou A, Trichopoulos D, Sacerdote C, Palli D, Tumino R, Agnoli C, Kiemeney LA, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Chirlaque MD, Ardanaz E, Larrañaga N, Quirós JR, Sánchez MJ, González CA, Stattin P, Hallmans G, Bingham S, Khaw KT, Rinaldi S, Slimani N, Jenab M, Riboli E, Key TJ (November 2008). "Fatty acid composition of plasma phospholipids and risk of prostate cancer in a case-control analysis nested within the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 88 (5): 1353–63. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.26369. PMID 18996872.

- Kurahashi N, Inoue M, Iwasaki M, Sasazuki S, Tsugane AS (April 2008). "Dairy product, saturated fatty acid, and calcium intake and prostate cancer in a prospective cohort of Japanese men". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 17 (4): 930–7. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2681. PMID 18398033. S2CID 551427.

- Corwin RL, Hartman TJ, Maczuga SA, Graubard BI (2006). "Dietary saturated fat intake is inversely associated with bone density in humans: Analysis of NHANES III". The Journal of Nutrition. 136 (1): 159–165. doi:10.1093/jn/136.1.159. PMID 16365076. S2CID 4443420.

- see the article Food pyramid (nutrition) for more information.

- "Choosing foods with healthy fats". Health Canada. 2018-10-10. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- "Cut Down on Saturated Fats" (PDF). United States Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- "Fat: the facts". United Kingdom's National Health Service. 2018-04-27. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- "Fat". Australia's National Health and Medical Research Council and Department of Health and Ageing. 2012-09-24. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- "Getting the Fats Right!". Singapore's Ministry of Health. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- "Health Diet". India's Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- "Eating and Activity Guidelines for New Zealand Adults" (PDF). New Zealand's Ministry of Health. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- "Know More about Fat". Hong Kong's Department of Health. Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation (2003). Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases (WHO technical report series 916) (PDF). World Health Organization. pp. 81–94. ISBN 978-92-4-120916-8. Retrieved 2016-04-04.

- "Trends in Intake of Energy, Protein, Carbohydrate, Fat, and Saturated Fat — United States, 1971–2000". Centers for Disease Control. 2004. Archived from the original on 2008-12-01.

- Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Brands M, Carnethon M, Daniels S, Franch HA, Franklin B, Kris-Etherton P, Harris WS, Howard B, Karanja N, Lefevre M, Rudel L, Sacks F, Van Horn L, Winston M, Wylie-Rosett J (July 2006). "Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee". Circulation. 114 (1): 82–96. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176158. PMID 16785338. S2CID 647269.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Smith SC, Jackson R, Pearson TA, Fuster V, Yusuf S, Faergeman O, Wood DA, Alderman M, Horgan J, Home P, Hunn M, Grundy SM (June 2004). "Principles for national and regional guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention: a scientific statement from the World Heart and Stroke Forum" (PDF). Circulation. 109 (25): 3112–21. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000133427.35111.67. PMID 15226228.

- "Dietary Guidelines for Americans" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. 2005.

- Eat less saturated fat

- Fats explained

- German JB, Dillard CJ (September 2004). "Saturated fats: what dietary intake?". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 80 (3): 550–559. doi:10.1093/ajcn/80.3.550. PMID 15321792.

- Zelman K (2011). "The Great Fat Debate: A Closer Look at the Controversy—Questioning the Validity of Age-Old Dietary Guidance". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 111 (5): 655–658. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2011.03.026. PMID 21515106.

Further reading

- Feinman RD (October 2010). "Saturated fat and health: recent advances in research". Lipids. 45 (10): 891–2. doi:10.1007/s11745-010-3446-8. PMC 2974200. PMID 20827513.

- Howard BV, Van Horn L, Hsia J, Manson JE, Stefanick ML, Wassertheil-Smoller S, et al. (2006). "Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Women's Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial". Journal of the American Medical Association. 295 (6): 655–66. doi:10.1001/jama.295.6.655. PMID 16467234.

- Zelman K (May 2011). "The great fat debate: a closer look at the controversy-questioning the validity of age-old dietary guidance". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 111 (5): 655–8. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2011.03.026. PMID 21515106.