Schläfli symbol

In geometry, the Schläfli symbol is a notation of the form {p,q,r,...} that defines regular polytopes and tessellations.

The Schläfli symbol is named after the 19th-century Swiss mathematician Ludwig Schläfli,[1]:143 who generalized Euclidean geometry to more than three dimensions and discovered all their convex regular polytopes, including the six that occur in four dimensions.

Definition

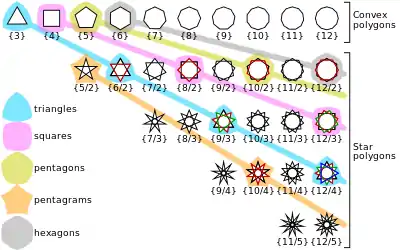

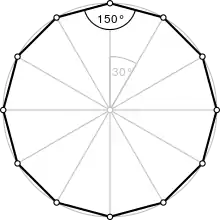

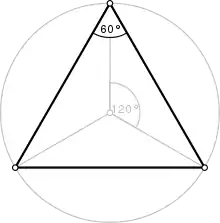

The Schläfli symbol is a recursive description,[1]:129 starting with {p} for a p-sided regular polygon that is convex. For example, {3} is an equilateral triangle, {4} is a square, {5} a convex regular pentagon and so on.

Regular star polygons are not convex, and their Schläfli symbols {p/q} contain irreducible fractions p/q, where p is the number of vertices, and q is their turning number. Equivalently, {p/q} is created from the vertices of {p}, connected every q. For example, {5⁄2} is a pentagram; {5⁄1} is a pentagon.

A regular polyhedron that has q regular p-sided polygon faces around each vertex is represented by {p,q}. For example, the cube has 3 squares around each vertex and is represented by {4,3}.

A regular 4-dimensional polytope, with r {p,q} regular polyhedral cells around each edge is represented by {p,q,r}. For example, a tesseract, {4,3,3}, has 3 cubes, {4,3}, around an edge.

In general, a regular polytope {p,q,r,...,y,z} has z {p,q,r,...,y} facets around every peak, where a peak is a vertex in a polyhedron, an edge in a 4-polytope, a face in a 5-polytope, a cell in a 6-polytope, and an (n-3)-face in an n-polytope.

Properties

A regular polytope has a regular vertex figure. The vertex figure of a regular polytope {p,q,r,...,y,z} is {q,r,...,y,z}.

Regular polytopes can have star polygon elements, like the pentagram, with symbol {5⁄2}, represented by the vertices of a pentagon but connected alternately.

The Schläfli symbol can represent a finite convex polyhedron, an infinite tessellation of Euclidean space, or an infinite tessellation of hyperbolic space, depending on the angle defect of the construction. A positive angle defect allows the vertex figure to fold into a higher dimension and loops back into itself as a polytope. A zero angle defect tessellates space of the same dimension as the facets. A negative angle defect cannot exist in ordinary space, but can be constructed in hyperbolic space.

Usually, a facet or a vertex figure is assumed to be a finite polytope, but can sometimes itself be considered a tessellation.

A regular polytope also has a dual polytope, represented by the Schläfli symbol elements in reverse order. A self-dual regular polytope will have a symmetric Schläfli symbol.

In addition to describing Euclidean polytopes, Schläfli symbols can be used to describe spherical polytopes or spherical honeycombs.[1]:138

History and variations

Schläfli's work was almost unknown in his lifetime, and his notation for describing polytopes was rediscovered independently by several others. In particular, Thorold Gosset rediscovered the Schläfli symbol which he wrote as | p | q | r | ... | z | rather than with brackets and commas as Schläfli did.[1]:144

Gosset's form has greater symmetry, so the number of dimensions is the number of vertical bars, and the symbol exactly includes the sub-symbols for facet and vertex figure. Gosset regarded | p as an operator, which can be applied to | q | ... | z | to produce a polytope with p-gonal faces whose vertex figure is | q | ... | z |.

Cases

Symmetry groups

Schläfli symbols are closely related to (finite) reflection symmetry groups, which correspond precisely to the finite Coxeter groups and are specified with the same indices, but square brackets instead [p,q,r,...]. Such groups are often named by the regular polytopes they generate. For example, [3,3] is the Coxeter group for reflective tetrahedral symmetry, [3,4] is reflective octahedral symmetry, and [3,5] is reflective icosahedral symmetry.

Regular polygons (plane)

The Schläfli symbol of a (convex) regular polygon with p edges is {p}. For example, a regular pentagon is represented by {5}.

For (nonconvex) star polygons, the constructive notation {p⁄q} is used, where p is the number of vertices and q - 1 is the number of vertices skipped when drawing each edge of the star. For example, {5⁄2} represents the pentagram.

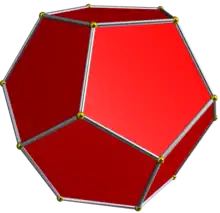

Regular polyhedra (3 dimensions)

The Schläfli symbol of a regular polyhedron is {p,q} if its faces are p-gons, and each vertex is surrounded by q faces (the vertex figure is a q-gon).

For example, {5,3} is the regular dodecahedron. It has pentagonal (5 edges) faces, and 3 pentagons around each vertex.

See the 5 convex Platonic solids, the 4 nonconvex Kepler-Poinsot polyhedra.

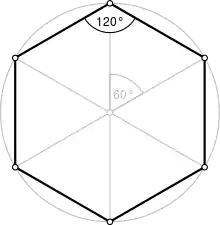

Topologically, a regular 2-dimensional tessellation may be regarded as similar to a (3-dimensional) polyhedron, but such that the angular defect is zero. Thus, Schläfli symbols may also be defined for regular tessellations of Euclidean or hyperbolic space in a similar way as for polyhedra. The analogy holds for higher dimensions.

For example, the hexagonal tiling is represented by {6,3}.

Regular 4-polytopes (4 dimensions)

The Schläfli symbol of a regular 4-polytope is of the form {p,q,r}. Its (two-dimensional) faces are regular p-gons ({p}), the cells are regular polyhedra of type {p,q}, the vertex figures are regular polyhedra of type {q,r}, and the edge figures are regular r-gons (type {r}).

See the six convex regular and 10 regular star 4-polytopes.

For example, the 120-cell is represented by {5,3,3}. It is made of dodecahedron cells {5,3}, and has 3 cells around each edge.

There is one regular tessellation of Euclidean 3-space: the cubic honeycomb, with a Schläfli symbol of {4,3,4}, made of cubic cells and 4 cubes around each edge.

There are also 4 regular compact hyperbolic tessellations including {5,3,4}, the hyperbolic small dodecahedral honeycomb, which fills space with dodecahedron cells.

Regular n-polytopes (higher dimensions)

For higher-dimensional regular polytopes, the Schläfli symbol is defined recursively as {p1, p2,...,pn − 1} if the facets have Schläfli symbol {p1,p2,...,pn − 2} and the vertex figures have Schläfli symbol {p2,p3,...,pn − 1}.

A vertex figure of a facet of a polytope and a facet of a vertex figure of the same polytope are the same: {p2,p3,...,pn − 2}.

There are only 3 regular polytopes in 5 dimensions and above: the simplex, {3,3,3,...,3}; the cross-polytope, {3,3, ..., 3,4}; and the hypercube, {4,3,3,...,3}. There are no non-convex regular polytopes above 4 dimensions.

Dual polytopes

If a polytope of dimension n ≥ 2 has Schläfli symbol {p1,p2, ..., pn − 1} then its dual has Schläfli symbol {pn − 1, ..., p2,p1}.

If the sequence is palindromic, i.e. the same forwards and backwards, the polytope is self-dual. Every regular polytope in 2 dimensions (polygon) is self-dual.

Prismatic polytopes

Uniform prismatic polytopes can be defined and named as a Cartesian product (with operator "×") of lower-dimensional regular polytopes.

- In 0D, a point is represented by ( ). Its Coxeter diagram is empty. Its Coxeter notation symmetry is ][.

- In 1D, a line segment is represented by { }. Its Coxeter diagram is

. Its symmetry is [ ].

. Its symmetry is [ ]. - In 2D, a rectangle is represented as { } × { }. Its Coxeter diagram is

. Its symmetry is [2].

. Its symmetry is [2]. - In 3D, a p-gonal prism is represented as { } × {p}. Its Coxeter diagram is

. Its symmetry is [2,p].

. Its symmetry is [2,p]. - In 4D, a uniform {p,q}-hedral prism is represented as { } × {p,q}. Its Coxeter diagram is

. Its symmetry is [2,p,q].

. Its symmetry is [2,p,q]. - In 4D, a uniform p-q duoprism is represented as {p} × {q}. Its Coxeter diagram is

. Its symmetry is [p,2,q].

. Its symmetry is [p,2,q].

The prismatic duals, or bipyramids can be represented as composite symbols, but with the addition operator, "+".

- In 2D, a rhombus is represented as { } + { }. Its Coxeter diagram is

. Its symmetry is [2].

. Its symmetry is [2]. - In 3D, a p-gonal bipyramid, is represented as { } + {p}. Its Coxeter diagram is

. Its symmetry is [2,p].

. Its symmetry is [2,p]. - In 4D, a {p,q}-hedral bipyramid is represented as { } + {p,q}. Its Coxeter diagram is

. Its symmetry is [p,q].

. Its symmetry is [p,q]. - In 4D, a p-q duopyramid is represented as {p} + {q}. Its Coxeter diagram is

. Its symmetry is [p,2,q].

. Its symmetry is [p,2,q].

Pyramidal polytopes containing vertices orthogonally offset can be represented using a join operator, "∨". Every pair of vertices between joined figures are connected by edges.

In 2D, an isosceles triangle can be represented as ( ) ∨ { } = ( ) ∨ [( ) ∨ ( )].

In 3D:

- A digonal disphenoid can be represented as { } ∨ { } = [( ) ∨ ( )] ∨ [( ) ∨ ( )].

- A p-gonal pyramid is represented as ( ) ∨ {p}.

In 4D:

- A p-q-hedral pyramid is represented as ( ) ∨ {p,q}.

- A 5-cell is represented as ( ) ∨ [( ) ∨ {3}] or [( ) ∨ ( )] ∨ {3} = { } ∨ {3}.

- A square pyramidal pyramid is represented as ( ) ∨ [( ) ∨ {4}] or [( ) ∨ ( )] ∨ {4} = { } ∨ {4}.

When mixing operators, the order of operations from highest to lowest is ×, +, ∨.

Axial polytopes containing vertices on parallel offset hyperplanes can be represented by the || operator. A uniform prism is {n}||{n} and antiprism {n}||r{n}.

Extension of Schläfli symbols

Polygons and circle tilings

A truncated regular polygon doubles in sides. A regular polygon with even sides can be halved. An altered even-sided regular 2n-gon generates a star figure compound, 2{n}.

| Form | Schläfli symbol | Symmetry | Coxeter diagram | Example, {6} | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular | {p} | [p] |  | Hexagon | |||

| Truncated | t{p} = {2p} | [[p]] = [2p] |  | Truncated hexagon (Dodecagon) | |||

| Altered and Holosnubbed |

a{2p} = β{p} | [2p] |  | Altered hexagon (Hexagram) | |||

| Half and Snubbed |

h{2p} = s{p} = {p} | [1+,2p] = [p] |  | Half hexagon (Triangle) | |||

Polyhedra and tilings

Coxeter expanded his usage of the Schläfli symbol to quasiregular polyhedra by adding a vertical dimension to the symbol. It was a starting point toward the more general Coxeter diagram. Norman Johnson simplified the notation for vertical symbols with an r prefix. The t-notation is the most general, and directly corresponds to the rings of the Coxeter diagram. Symbols have a corresponding alternation, replacing rings with holes in a Coxeter diagram and h prefix standing for half, construction limited by the requirement that neighboring branches must be even-ordered and cuts the symmetry order in half. A related operator, a for altered, is shown with two nested holes, represents a compound polyhedra with both alternated halves, retaining the original full symmetry. A snub is a half form of a truncation, and a holosnub is both halves of an alternated truncation.

| Form | Schläfli symbols | Symmetry | Coxeter diagram | Example, {4,3} | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular | {p,q} | t0{p,q} | [p,q] or [(p,q,2)] |

Cube | |||||

| Truncated | t{p,q} | t0,1{p,q} | Truncated cube | ||||||

| Bitruncation (Truncated dual) |

2t{p,q} | t1,2{p,q} | Truncated octahedron | ||||||

| Rectified (Quasiregular) |

r{p,q} | t1{p,q} | Cuboctahedron | ||||||

| Birectification (Regular dual) |

2r{p,q} | t2{p,q} | Octahedron | ||||||

| Cantellated (Rectified rectified) |

rr{p,q} | t0,2{p,q} | Rhombicuboctahedron | ||||||

| Cantitruncated (Truncated rectified) |

tr{p,q} | t0,1,2{p,q} | Truncated cuboctahedron | ||||||

Alternations, quarters and snubs

Alternations have half the symmetry of the Coxeter groups and are represented by unfilled rings. There are two choices possible on which half of vertices are taken, but the symbol doesn't imply which one. Quarter forms are shown here with a + inside a hollow ring to imply they are two independent alternations.

| Form | Schläfli symbols | Symmetry | Coxeter diagram | Example, {4,3} | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternated (half) regular | h{2p,q} | ht0{2p,q} | [1+,2p,q] | Demicube (Tetrahedron) | |||||

| Snub regular | s{p,2q} | ht0,1{p,2q} | [p+,2q] | ||||||

| Snub dual regular | s{q,2p} | ht1,2{2p,q} | [2p,q+] | Snub octahedron (Icosahedron) | |||||

| Alternated rectified (p and q are even) |

hr{p,q} | ht1{p,q} | [p,1+,q] | ||||||

| Alternated rectified rectified (p and q are even) |

hrr{p,q} | ht0,2{p,q} | [(p,q,2+)] | ||||||

| Quartered (p and q are even) |

q{p,q} | ht0ht2{p,q} | [1+,p,q,1+] | ||||||

| Snub rectified Snub quasiregular |

sr{p,q} | ht0,1,2{p,q} | [p,q]+ | Snub cuboctahedron (Snub cube) | |||||

Altered and holosnubbed

Altered and holosnubbed forms have the full symmetry of the Coxeter group, and are represented by double unfilled rings, but may be represented as compounds.

| Form | Schläfli symbols | Symmetry | Coxeter diagram | Example, {4,3} | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altered regular | a{p,q} | at0{p,q} | [p,q] | Stellated octahedron | |||||

| Holosnub dual regular | ß{q, p} | ß{q,p} | at0,1{q,p} | [p,q] | Compound of two icosahedra | ||||

Polychora and honeycombs

| Form | Schläfli symbol | Coxeter diagram | Example, {4,3,3} | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular | {p,q,r} | t0{p,q,r} | Tesseract | |||||

| Truncated | t{p,q,r} | t0,1{p,q,r} | Truncated tesseract | |||||

| Rectified | r{p,q,r} | t1{p,q,r} | Rectified tesseract | |||||

| Bitruncated | 2t{p,q,r} | t1,2{p,q,r} | Bitruncated tesseract | |||||

| Birectified (Rectified dual) |

2r{p,q,r} = r{r,q,p} | t2{p,q,r} | Rectified 16-cell | |||||

| Tritruncated (Truncated dual) |

3t{p,q,r} = t{r,q,p} | t2,3{p,q,r} | Bitruncated tesseract | |||||

| Trirectified (Dual) |

3r{p,q,r} = {r,q,p} | t3{p,q,r} = {r,q,p} | 16-cell | |||||

| Cantellated | rr{p,q,r} | t0,2{p,q,r} | Cantellated tesseract | |||||

| Cantitruncated | tr{p,q,r} | t0,1,2{p,q,r} | Cantitruncated tesseract | |||||

| Runcinated (Expanded) |

e3{p,q,r} | t0,3{p,q,r} | Runcinated tesseract | |||||

| Runcitruncated | t0,1,3{p,q,r} | Runcitruncated tesseract | ||||||

| Omnitruncated | t0,1,2,3{p,q,r} | Omnitruncated tesseract | ||||||

Alternations, quarters and snubs

| Form | Schläfli symbol | Coxeter diagram | Example, {4,3,3} | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternations | |||||||||

| Half p even |

h{p,q,r} | ht0{p,q,r} | 16-cell | ||||||

| Quarter p and r even |

q{p,q,r} | ht0ht3{p,q,r} | |||||||

| Snub q even |

s{p,q,r} | ht0,1{p,q,r} | Snub 24-cell | ||||||

| Snub rectified r even |

sr{p,q,r} | ht0,1,2{p,q,r} | Snub 24-cell | ||||||

| Alternated duoprism | s{p}s{q} | ht0,1,2,3{p,2,q} | Great duoantiprism | ||||||

Bifurcating families

| Form | Extended Schläfli symbol | Coxeter diagram | Examples | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quasiregular | {p,q1,1} | t0{p,q1,1} | 16-cell | |||||

| Truncated | t{p,q1,1} | t0,1{p,q1,1} | Truncated 16-cell | |||||

| Rectified | r{p,q1,1} | t1{p,q1,1} | 24-cell | |||||

| Cantellated | rr{p,q1,1} | t0,2,3{p,q1,1} | Cantellated 16-cell | |||||

| Cantitruncated | tr{p,q1,1} | t0,1,2,3{p,q1,1} | Cantitruncated 16-cell | |||||

| Snub rectified | sr{p,q1,1} | ht0,1,2,3{p,q1,1} | Snub 24-cell | |||||

| Quasiregular | {r,/q\,p} | t0{r,/q\,p} | ||||||

| Truncated | t{r,/q\,p} | t0,1{r,/q\,p} | ||||||

| Rectified | r{r,/q\,p} | t1{r,/q\,p} | ||||||

| Cantellated | rr{r,/q\,p} | t0,2,3{r,/q\,p} | ||||||

| Cantitruncated | tr{r,/q\,p} | t0,1,2,3{r,/q\,p} | ||||||

| Snub rectified | sr{p,/q,\r} | ht0,1,2,3{p,/q\,r} | ||||||

Tessellations

Regular

Semi-regular

References

- Coxeter, H.S.M. (1973). Regular Polytopes (3rd ed.). New York: Dover.

Sources

- Coxeter, Harold Scott MacDonald (1973) [1948]. Regular Polytopes (3rd ed.). Dover Publications. pp. 14, 69, 149. ISBN 0-486-61480-8. OCLC 798003.

Regular Polytopes.

- Sherk, F. Arthur; McMullen, Peter; Thompson, Anthony C.; Weiss, Asia Ivic, eds. (1995). Kaleidoscopes: Selected Writings of H.S.M. Coxeter. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-01003-6.

- (Paper 22) pp. 251–278 Coxeter, H.S.M. (1940). "Regular and Semi Regular Polytopes I". Math. Zeit. 46: 380–407. doi:10.1007/BF01181449. Zbl 0022.38305. MR 2,10

- (Paper 23) pp. 279–312 — (1985). "Regular and Semi-Regular Polytopes II". Math. Zeit. 188 (4): 559–591. doi:10.1007/BF01161657. Zbl 0547.52005.

- (Paper 24) pp. 313–358 — (1988). "Regular and Semi-Regular Polytopes III". Math. Zeit. 200 (1): 3–45. doi:10.1007/BF01161745. Zbl 0633.52006.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Schläfli Symbol". MathWorld. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- Starck, Maurice (April 13, 2012). "Polyhedral Names and Notations". A Ride Through the Polyhedra World. Retrieved December 28, 2019.