Senate bean soup

U.S. Senate Bean Soup or simply Senate bean soup is a soup made with navy beans, ham hocks, and onion. It is served in the dining room of the United States Senate every day, in a tradition that dates back to the early 20th century. The original version included celery, garlic, parsley, and possibly mashed potatoes as well.

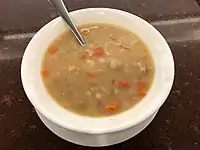

Senate bean soup at the Capitol Visitor Center | |

| Alternative names | U.S. Senate Bean Soup |

|---|---|

| Course | Soup |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Region or state | United States Senate |

| Main ingredients | Navy beans, ham hocks, sometimes mashed potatoes |

Tradition

According to the Senate website, "Bean soup is on the menu in the Senate's restaurant every day. There are several stories about the origin of that mandate, but none has been corroborated."[1][2]

On September 14, 1943, rationing due to World War II left the Senate kitchen without enough navy beans to serve the soup. The Washington Times-Herald reported on its absence the following day. In a speech on the Senate floor in 1988, Bob Dole recounted the response to the crisis: "Somehow, by the next day, more beans were found and bowls of bean soup have been ladled up without interruption ever since."[3]

Recipes

Senate versions

A 1967 memo from the Architect of the Capitol to the Librarian of the Senate describes the modern recipe, calling for "two pounds of small Michigan Navy Beans".[4]

John Egerton writes in Southern Food that the use of ham hocks suggests an origin in Southern cuisine. Although the legislators credited with institutionalizing the soup did not represent Southern states, most of the cooks at the time were black Southerners who would prepare bean soup in their own style.[5] There was a period when the Senate dining services omitted the ham and instead used a soup base. In 1984, a new manager discovered this practice; he reflects, "we went back to the ham hocks, and there was a real difference."[6]

There are two Senate soup recipes:

The Famous Senate Restaurant Bean Soup Recipe

2 pounds [0.91 kg] dried navy beans

four US quarts [3.8 l] hot water

1 1⁄2 pounds [0.68 kg] smoked ham hocks

1 onion, chopped

2 tablespoons butter

salt and pepper to taste

Wash the navy beans and run hot water through them until they are slightly whitened. Place beans into pot with hot water. Add ham hocks and simmer approximately three hours in a covered pot, stirring occasionally. Remove ham hocks and set aside to cool. Dice meat and return to soup. Lightly brown the onion in butter. Add to soup. Before serving, bring to a boil and season with salt and pepper. Serves 8.[2]

Bean Soup Recipe (for five gallons)

3 pounds dried navy beans

2 pounds of ham and a ham bone

1 quart mashed potatoes

5 onions, chopped

2 stalks of celery, chopped

four cloves garlic, chopped

half a bunch of parsley, chopped

Clean the beans, then cook them dry. Add ham, bone and water and bring to a boil. Add potatoes and mix thoroughly. Add chopped vegetables and bring to a boil. Simmer for one hour before serving.[2]

Reviews and variants

According to The Best Soups in the World, "most reports ... suggest that it unfortunately leaves a lot to be desired."[7]

Availability

As of 2010, members of the public can try the soup between 11:30am and 3pm in the Senate dining room. There is a dress code, and entry requires a "request letter" from a senator. The soup is also available to the general public at the Capitol Visitor Center restaurant on a rotating basis, between 7:30am and 4pm,[8] and in the Longworth Cafeteria, between 7:30am and 2:30pm.[9]

The Project Greek Island bunker, a Cold War-era emergency relocation center for Congress, included a cafeteria that would have served Senate bean soup.[10]

Past prices for a bowl include:

See also

- List of bean soups

- List of ham dishes – also includes ham hock dishes

- List of legume dishes

- Traditions of the United States Senate

Notes

- Senate 2003.

- "Official recipe, Senate Bean Soup". United States Senate. Retrieved March 26, 2014.

- Frey 2003.

- Kessler 1998, p. 257.

- Egerton 1993, p. 274.

- Kessler 1998, p. 74.

- Wright 2009, pp. 131–132.

- Salwa 2010, p. 159.

- Salwa 2009, p. 141.

- Leebaert 2003, p. 241.

- Pearson & Allen 1940, p. 7.

- Carlson 2003, pp. 218–219.

- Kessler 1997, p. 48.

- Rubin 2004, pp. 8, 84.

- Rubin 2008, p. 94.

- Rubin 2010, p. 81.

References

- Associated Press (18 February 1927), "Senators differ on their menus, bean soup liked", The Helena Daily Independent, p. 9

- Carlson, Margaret (2003), "Good-bye to Whatever Man", Anyone can grow up: how George Bush and I made it to the White House, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-684-80890-0

- Egerton, John (1993), Southern food: at home, on the road, in history, University of North Carolina Press, p. 274, ISBN 0-8078-4417-9

- Frey, Jennifer (7 July 2003), "Hill of Beans; In the Capitol's Senate Dining Room, A Bipartisan Favorite Served 100 Years", The Washington Post, p. C01, Factiva WP00000020030707dz770002t

- Kessler, Marsha E. (30 October 1997), "Statement of Marsha E. Kessler, Vice President, Copyright Royalty Distribution, Motion Picture Association of America", in Coble, Howard (ed.), Copyright Licensing Regimes Covering Retransmission of Broadcast Signals: Hearing Before the Committee on the Judiciary, U.S. House of Representatives, Diane Publishing

- Kessler, Ronald (August 1998), Inside Congress: The Shocking Scandals, Corruption, and Abuse of Power Behind the Scenes on Capitol Hill, Pocket Books, ISBN 0-671-00386-0

- Leebaert, Derek (May 2003), The fifty-year wound: how America's Cold War victory shapes our world (1st paperback ed.), Back Bay, ISBN 0-316-16496-8

- Pearson, Drew; Allen, Robert S. (12 April 1940), "The Washington Merry-Go-Round: Bean Soup", Olean Times Herald, p. 7

- Rubin, Beth (2004), Washington D.C. with Kids (7th ed.), Frommer's, ISBN 0-7645-4302-4

- Rubin, Beth (2008), Washington D.C. with Kids (9th ed.), Frommer's, ISBN 978-0-470-18196-6

- Rubin, Beth (2010), Washington D.C. with Kids (10th ed.), Frommer's, ISBN 978-0-470-55612-2

- Jabado, Salwa, ed. (2009), Washington, D.C. 2009: With Mount Vernon, Alexandria & Annapolis, Fodor's, ISBN 978-1-4000-1963-2

- Jabado, Salwa, ed. (2010), Washington, D.C. 2010: With Mount Vernon, Alexandria & Annapolis, Fodor's, ISBN 978-1-4000-0855-1

- Secretary of the Senate, ed. (2003), "Senate Bean Soup", senate.gov, retrieved 13 September 2010

- Wright, Clifford A. (2009), The Best Soups in the World, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-470-18052-5

External links

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

- Senate Bean Soup Recipe - from the official website of the United States Senate, accessed 27 October 2013.

.jpg.webp)