Languages of Somalia

This page articulates the languages spoken in Somalia. The endoglossic language of Somalia has always been the Somali language, although throughout Somalia's history various exoglossic languages have also been effectuated at a national level.[1] The languages which are specifically spoken in the islands off the Somali coast include Seychellois Creole, the Soqotri language and Tikulu.

| Languages of Somalia | |

|---|---|

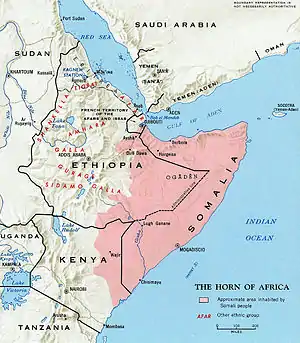

Map of Somali language distribution.af soomaali | |

| Official | Somali, Arabic |

| Regional | Maay Maay (South West) Soqotri (Puntland) |

| Immigrant | Oromo, Mushunguli |

| Foreign | English, Italian |

| Signed | Somali Sign Language |

| Keyboard layout | |

Cushitic and Horner languages

Somali language

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Somalia |

|---|

| Culture |

| People |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Politics |

|

Somali is the official language of Somalia and as the mother tongue of the Somali people, is also its endoglossic language.[2][3][4] It is a member of the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic family, and its nearest relatives are the Afar and Saho languages.[5] Somali is the best documented of the Cushitic languages,[6] with academic studies of it dating from before 1900.

As of 2006, there were approximately 16.6 million speakers of Somali, of which about 8.3 million reside in Somalia.[7] Of the six Somali federal states, all of them solely implement the Af-Maxaa-tiri dialect, except for the South West state, which officially uses it in combination with the Af-Maay-tiri, commonly known as Maay Maay.[8] The Somali language is spoken by ethnic Somalis in Greater Somalia and the Somali diaspora. It is spoken as an adoptive language by a few ethnic minority groups in these regions.

Somali dialects are divided into three main groups: Northern, Benaadir and Maay (sometimes spelled Mai or Mai Mai). Northern Somali (or Northern-Central Somali) forms the basis for Standard Somali. Benaadir (also known as Coastal Somali) is spoken on the Benadir coast from Cadaley to south of Merca, including Mogadishu, as well as in the immediate hinterland. The coastal dialects have additional phonemes which do not exist in Standard Somali. Maay is principally spoken by the Digil and Mirifle (Rahanweyn) clans in South West.[9]

The Somali language is regulated by the Regional Somali Language Academy, an intergovernmental institution established in June 2013 by the governments of Djibouti, Somalia and Ethiopia. It is officially mandated with preserving the Somali language.[10]

Somali Sign Language

The Somali Sign Language (SSL) is a sign language used by the deaf community in Somalia and Djibouti. It was originally developed by a Somali man educated in a Somali deaf school in Wajir, Kenya. In 1997, he established the first school for the deaf in the city of Borama, Somalia.

Afar

During the mid-16th century, much of the northern Horn, stretching from the hinterlands of the Gulf of Tadjoura up the northeastern coast of Somalia functioned under a single polity called the Adal Sultanate. The Adal Sultanate merged the Afar-speaking Dankali Sultanate with the Somali-speaking Ifat Sultanate. The amalgamation of this region meant that both languages were mutually spoken in one another's regions.[11]

Minorities

Other minority languages include Bravanese (also known as Chimwiini or Chimbalazi), a variant of the Bantu Swahili language that is spoken along the southern coast by the Bravanese people. Kibajuni is a Swahili dialect that is the mother tongue of the Bajuni ethnic minority group. Additionally, a number of Bantus speak Mushunguli as a mother tongue.[12]

Vulnerable Cushitic languages

- Garre Garre language (57,500 speakers as of 1992)

- Tunni[13] Tunni language (23,000 speakers as of 2006)

Endangered Cushitic languages

- Aweer Aweer language, also known as "Boni", Waata, Wata, Sanye, Wasanye, Waboni, Bon, Ogoda, or Wata-Bala (Less than 200 speakers)

- Boon Boni language, also known as Af-Boon or Boni (59 speakers as of 2000).

Endangered Atlantic-Congo languages

- Mushungulu, also known as Kimushungulu or Mushunguli language (23,000 speakers as of 2006).

Adjacent islands

In 2010, Somalia claimed that the island of Socotra, wherein Soqotri is spoken, should be instilled as part of its sovereignty, argueing that the archipelago is situated nearer to the African coast than to the Arabian coast.[14] With regards to other islands adjacent to the Somali coast, the Kibajuni is a Swahili dialect that is the mother tongue of the Bajuni ethnic group in the eponymously named islands off Jubalands coast.[12] In this island which is part of Jubaland, this language is spoken alongside Somali. A few hundred miles further up, outside of Somalia's jurisdiction and territorial waters, Seychellois Creole is spoken in Seychelles, which lies at a distance of about 835 mi (1,344 km) across the Somali sea from the Somali coast.[15] Seychellois Creole is a French based pidgin and creole language, whose parent language, French, is spoken at formal functions of education of administration in the Somali-majority nation of Djibouti.[16]

Semitic languages

Arabic

In addition to Somali, Arabic, which is also an Afro-Asiatic tongue, is an official language in Somalia, although as a non-indigenous language, it is considered exoglossic.[2][3] SIL estimates the total number of speakers, regardless of proficiency, at just over two million.[17] with the Yemeni and Hadhrami dialects being the most common.[18] However, other analysts have argued that Somalis are overall not adept at the language, don't speak it at all, or only a little.[19][20]

Af-Somali's main lexical borrowings come from Arabic. Soravia (1994) noted a total of 1,436 Arabic loanwords in Agostini a.o. 1985, a prominent Somali dictionary. Most of the vocabulary terms consisted of commonly used nouns and a few words that Zaborski (1967:122) observed in the older literature were absent in Agostini's later work.[21] The parallel disparity between the Arabic and Somali languages occurred despite a lengthy spell of a shared religion, as well as frequent intermingling as with through practises such as umrah. This can be attributed to each having a separate developments from the primitive Afro-Asiatic language as well as a sea separating the speakers of the two languages. Furthermore, Mr Bruce, an 18th-century voyager of the Horn of Africa, was reported by author George Annesley to have described Somalis as an Arabophobic race which had disdain for Arabs writing "an Arab, a nation whom they detest".[22]

Somalis rarely speak Arabic in their day to day lives in all regions of greater Somalia including Somalia/Somaliland/Djibouti

Soqotri

Due to the close distance between Somalia and Socotra, there has always been extensive relations between the two peoples particularly with the nearby region of Puntland which is the nearest mainland shore to Socotra. These interactions between Puntites and Soqotris include instances of aid during shipwrecks on either coasts, trade as well as the exchange of cultural facets and trade. These interactions have also meant that some inhabitants of localities of the nearest linear proximity such as Bereeda and Alula have become bilingual at both the Soqotri and Somali languages.[23]

European languages

Italian

Italian was the main official language in Italian Somaliland, although following its acquisition of Jubaland in 1924, the Jubaland region maintained English at a semi-official status for several years thereafter.[24] During the United Nations Trusteeship period from 1949 until 1960, Italian along with Somali were used at an official level internally, whilst the UN's main working language of English was the language used during diplomatic, international and occasionally for economic correspondence.[25] After 1960 independence, the Italian remained official for another nine years. Italian was later declared an official language again by the Transitional Federal Government along with English in 2004.[26] But, in 2012, they were later removed by the establishments of the Provisional Constitution by the Federal Government of Somalia[27] leaving Somali and Arabic as the only official languages.

Italian is a legacy of the Italian colonial period of Somalia when it was part of the Italian Empire. Italian was the mother tongue of the Italian settlers of Somalia.

Although it was the primary language since colonial rule, Italian continued to be used among the country's ruling elite even after 1960 independence when it continued to remain as an official language. It is estimated that more than 200,000 native Somalis (nearly 20% of the total population of former Somalia italiana) were fluent speaking Italian when independence was declared in 1960.[28]

After a military coup in 1969, all foreign entities were nationalized by Siad Barre (who spoke Italian fluently), including Mogadishu's principal university, which was renamed 'Jaamacadda Ummadda Soomaliyeed' (Somali National University). This marked the initial decline of the use of Italian in Somalia.

However, Italian is still widely spoken by the elderly, the educated, and by the governmental officials of Somalia. Prior to the Somali civil war, Mogadishu still had an Italian-language school, but was later destroyed by the conflict.[29]

English

English is widely taught in schools. It used to be a working language in the British Somali Coast Protectorate in the north of the country. It was also increasing in usage during the British Military Administration (Somali) BMAS, whereby Britain controlled most Somali-inhabited areas from 1941 until 1949. Outside of the north, the Jubaland region has had the lengthiest period whereby English was an official language as the British empire began administering from the 1880s.[30] As such, English had been an official language in Jubaland in the five decades stretching from the 1880s to 1920s, and subsequently at a semi-official level during the BMAS (1940s), and UN Trusteeship (1950s) decades respectively.[31] The official government website is currently only available in English.

Darwiish period

The increase of Turkish in Somali multilingualism in the contemporary era dates to the late 1880s and early 1990s during Ismail Urwayni and his student Ali Nayroobi's efforts at spreading "Somali Salihism", the religious component of the Darwiish, through connections in the Ottoman Empire. Turkish is also spoken in modest numbers in Somalia. In contemporary periods, this is because the largest number of foreign students study in colleges or universities in Turkey after they received scholarships from Ankara's government. Other reasons include the presence of educational facilities built through assistance by the Turkish government and the various training programs in the Turkish language that accompanied it.[32] In more distant history, Turkish was first introduced during interaction between the mostly Turkish Ottomans and the Adal and Ajuraan sultanates respectively. The alliance between the Ottomans and the Darwiish State included Turkish translators during diplomatic negotiations or the exchange of ambassadors between the Ottomans and the Darwiish.[33][34]

Portuguese

The Portuguese empire began making inroads into the region of modern Jubaland from the 16th century. It maintained a foothold on Jubaland's coastal areas until its defeat by the Ajuran Sultanate in a naval battle and subsequently the Portuguese language ceased being used.[35]

Orthography

A number of writing systems have been used for transcribing the Somali language. Of these, the Somali Latin alphabet is the most widely used, and has been the official writing script in Somalia since 1972.[36] The script was developed by a number of leading scholars of Somali, including Musa Haji Ismail Galal, B. W. Andrzejewski and Shire Jama Ahmed specifically for transcribing the Somali language, and uses all letters of the English Latin alphabet except p, v and z.[37][38] There are no diacritics or other special characters except the use of the apostrophe for the glottal stop, which does not occur word-initially. There are three consonant digraphs: DH, KH and SH. Tone is not marked, and front and back vowels are not distinguished.

Besides Ahmed's Latin script, other orthographies that have been used for centuries for writing Somali include the long-established Arabic script and Wadaad's writing.[39] Indigenous writing systems developed in the twentieth century include the Osmanya, Borama and Kaddare scripts, which were invented by Osman Yusuf Kenadid, Sheikh Abdurahman Sheikh Nuur and Hussein Sheikh Ahmed Kaddare, respectively.[40]

Notes

- Eno, Mohamed A., Abderrazak Dammak, and Omar A. Eno. "From linguistic imperialism to language domination." Journal of Somali Studies 3.1-2 (2016): 9-52.

- Onwuegbule, Chinyere Gift, Chukwuka A. Chukwueke, and Nkama Anthony Ezeuduma. "OPTIMAL INDIGENOUS LANGUAGE USE AS STRATEGY FOR NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT." The Melting Pot 4.1 (2018).

- "The Federal Republic of Somalia - Provisional Constitution" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

The official language of the Federal Republic of Somalia is Somali (Maay and Maxaa-tiri), and Arabic is the second language.

- "Somalia". World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 2009-05-14. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- I. M. Lewis, Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho, (Red Sea Press: 1998), p.11.

- Lecarme, Jacqueline; Maury, Carole (1987). "A software tool for research in linguistics and lexicography: Application to Somali". Computers and Translation. 2: 21–36. doi:10.1007/BF01540131. S2CID 6515240.

- "Somali". SIL International. 2013. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- Taylor, Christian, Tanner Semmelrock, and Alexandra McDermott. "The Cost of Defection: The Consequences of Quitting Al-Shabaab." International Journal of Conflict and Violence (IJCV) 13 (2019): a657-a657.

- Andrew Dalby, Dictionary of languages: the definitive reference to more than 400 languages, (Columbia University Press: 1998), p.571.

- "Regional Somali Language Academy Launched in Djibouti". COMESA Regional Investment Agency. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- Wilson, Richard Trevor. "Populations and production of fat-tailed and fat-rumped sheep in the Horn of Africa." Tropical animal health and production 43.7 (2011): 1419-1425.

- "Mushungulu". Ethnologue.

- "Did you know Tunni is vulnerable?". Endangered Languages. Retrieved 2019-12-17.

- "For First Time in History, Somalia Claims Socotra as Its Own hiv and aids statistics treatment of hiv aids hiv statisticsbest free text spy app spy text app 100 free spy apps for androidchlamydia test kits stdstory.com early signs of chlamydia- Yemen Post English Newspaper Online". www.yemenpost.net. Retrieved 2020-12-12.

- Werema, Gilbert. "Safeguarding Tourism and Tuna: Seychelles’ Fight against the Somali Piracy Problem." (2012).

- Alwan, Daoud Aboubaker, Daoud Alwan Aboubaker, and Yohanis Mibrathu. Historical dictionary of Djibouti. No. 82. Scarecrow Press, 2000.

- "Somalia". Ethnologue.

- Dalby, Andrew (1999). Dictionary of Languages: The Definitive Reference to More Than 400 Languages. Bloomsbury Pub Ltd. p. 25. ISBN 0231115687.

- "Arabic, Standard". Ethnologue.

- Ekblad, Solvig, Andrea Linander, and Maria Asplund. "An exploration of the connection between two meaning perspectives: an evidence-based approach to health information delivery to vulnerable groups of Arabic-and Somali-speaking asylum seekers in a Swedish context." Global health promotion 19.3 (2012): 21-31.

- Versteegh (2008:273)

- Annesley, George (1809). Voyages and travels to India, Ceylon, the Red Sea, Abyssinia, and Egypt. p. 377.

- Zajonz, Uwe, et al. "The coastal fishes and fisheries of the Socotra Archipelago, Yemen." Marine pollution bulletin 105.2 (2016): 660-675

- Blaha, David Ryan. Pushing Marginalization: British Colonial Policy, Somali Identity, and the Gosha'Other'in Jubaland Province, 1895 to 1925. Diss. Virginia Tech, 2011.

- Strangio, Donatella. "The Somali People: Between Trusteeship and Independence." The Reasons for Underdevelopment. Physica, Heidelberg, 2012. 1-37.

- According to article 7 of Transitional Federal Charter for the Somali Republic: The official languages of the Somali Republic shall be Somali (Maay and Maxaatiri) and Arabic. The second languages of the Transitional Federal Government shall be English and Italian.

- According to article 5 of Provisional Constitution: The official language of the Federal Republic of Somalia is Somali (Maay and Maxaa-tiri), and Arabic is the second language.

- "Somalia Dieci Anni dopo" – via www.youtube.com.

- Scuola media di Mogadiscio (Picture)

- Oliver, Roland Anthony (1976). History of East Africa, Volume 2. Clarendon Press. p. 7.

- Hadden, Robert L. The geology of Somalia: A selected bibliography of Somalian geology, geography and earth science. ARMY TOPOGRAPHIC ENGINEERING CENTER ALEXANDRIA VA, 2007.

- Ozkan, Mehmet, and Serhat Orakci. "Turkey as a “political” actor in Africa–an assessment of Turkish involvement in Somalia." Journal of Eastern African Studies 9.2 (2015): 343-352

- Abdullahi, Abdurahman. Making Sense of Somali History: Volume 1. Vol. 1. Adonis and Abbey Publishers, 2017

- Xasuus qor: timelines of Somali history, 1400-2000 - Page 29, Faarax Maxamuud Maxamed - 2004

- Pouwels, Randall L. (2006). Horn and Crescent: Cultural Change and Traditional Islam on the East African Coast, 800–1900. African Studies. 53. Cambridge University Press. p. 15.

- Economist Intelligence Unit (Great Britain), Middle East annual review, (1975), p.229

- Abdullahi, Mohamed Diriye (2001). Culture and Customs of Somalia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-313-31333-2.

- Lewis, I. M. (1999). A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. James Currey Publishers. ISBN 978-0-85255-280-3.

- "Somali alphabets, pronunciation and language". www.omniglot.com.

- Laitin (1977:86–87)

References

- Diriye Abdullahi, Mohamed. 2000. Le Somali, dialectes et histoire. Ph.D. dissertation, Université de Montréal.

- Saeed, John Ibrahim. 1987. Somali Reference Grammar. Springfield, VA: Dunwoody Press.

- Saeed, John Ibrahim. 1999. Somali. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.