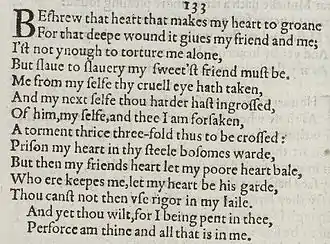

Sonnet 133

Sonnet 133 is a poem in sonnet form written by William Shakespeare, first published in 1609.

| Sonnet 133 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sonnet 133 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Overview

Critics generally agree that Sonnet 133 addresses the complex relationship between the speaker and an unidentified woman. Josephine Roberts interprets the sonnet in that the poet expresses a "fractured sense of self" [2] as a result of his toxic relationship with the dark lady. Her interpretation of the relationship as "toxic" is evident in the emotional plea that resounds throughout the sonnet. The sonnets prior to this address a young man referred to as a close friend of the speaker who is thus addressed as well in sonnet 133. According to critic A. L. Rowse, this sonnet gives the speaker's view of both his relation of the young man as his friend and the mistress.[3] Rowse's interpretation is supported by how the sonnet clearly describes the pain the unknown woman has inflicted upon both the young man and the speaker, "For that deep wound it gives my friend and me!"

Structure

Sonnet 133 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet has three quatrains, followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the typical rhyme scheme of the form ABAB CDCD EFEF GG and is composed in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The 1st line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / Beshrew that heart that makes my heart to groan (133.1)

Line 5 exhibits two common metrical variations: an initial reversal, and a final extrametrical syllable or feminine ending:

/ × × / × /× / × /(×) Me from myself thy cruel eye hath taken, (133.5)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus. (×) = extrametrical syllable.

Line 7 also (necessarily, given the rhyme scheme) has a feminine ending. An initial reversal occurs in line 9. A mid-line reversal occurs in line 8 — "thus to" — "threefold", while typically stressed on the first syllable, does not constitute a reversal because it is a double-stressed word, and in context the stress can shift to the second syllable.

Line 2 begins with the rightward movement of the first ictus (resulting in a four-position figure, × × / /, sometimes referred to as a minor ionic):

× × / / × / × / × / For that deep wound it gives my friend and me! (133.2)

Lines 4 and 6 also contain minor ionics, and line 9 potentially does.

The meter demands that line 13's "being" function as one syllable.[4]

Analysis

Helen Vendler describes the stages of the sonnet in that it begins with a listing of the conflict in Quatrain One then proceeds in Quatrain Two to show the effects and complications. Specifically the problem of this sonnet is the torture the dark lady has caused the two men to suffer. The effects and complications of this situation are pronounced throughout Quatrain Two indicating that the speaker may recover but the young man is reduced to her slave under her influence. In Quatrain Three, Vendler says that the "intolerable complication of effect" forces a request for relief and intelligibility which end in a helpless giving up reflected in the couplet.[5]

Analyzing specific words within the sonnets gives further evidence of the Quatrain transition. It begins with the first line in which the speaker declares that he is separate from her by saying "that heart (of hers) makes my heart groan".[6] Although he declares himself separate from her, her cruel eye has taken the speaker from himself and not only this, but she has taken his "next self", which refers to his friend as addressed earlier in the sonnets. Stephen Booth further explains this point arguing that the implied logic of lines 3 and 4 suggest that if the Dark Lady possesses the friend then she should release the speaker. He also addressed the cruel eye of the speaker saying that Sonnet 133 continues the theme of hearts and eyes from Sonnet 132, and Booth notes the shift from the friend's image of "mourning eyes" to the "cruel eye"(line 5) of the mistress. Booth continues his analysis with lines 10-11 of which he suggests that they, "add one more element to the verbal complexities and confusions by which the complex and confused three-way love affair is both reported and imitated".[7] Helen Vendler emphasizes his point by explaining that now the friend is enslaved by her as well as the speaker as evidenced in the final line of the couplet, "Perforce am thine, and all that is mine" (Line 14). She says that because he belongs to her he is thus forsaken.[8] Both Booth and Vendler suggest that everything that belongs to the speaker, including his friend's heart, bears the surrender to the dark lady.

The Dark Lady and the "Friend"

Because sonnet 133 is the first to directly refer to the "friend",[9] there is some controversy concerning the subject of that word. Joel Fineman argues that in this sonnet, the poet feels trapped by the Dark Lady, who represents the constraints of a heteronormative society. She has taken the "friend", or the poet's homosexual side, from him, preventing the poet from living in his self-created utopia of homosexuality with the Young Man.[10] Unlike the young man sequence, in which the poet "defines his own identity [. . .] as poet and lover", in the Dark Lady sequence, particularly sonnet 133, "the poet-lover of the [D]ark [L]ady will discover both himself and his poetry in the loss produced by the fracture of [his ideal identification as homosexual]".[11] Other critics argue that the Dark Lady has enslaved a literal friend, the Young Man,[12] creating a love triangle between the poet, the Young Man and the Dark Lady.[13] "The suggestion is that the friend had gone to woo the lady for the poet and, according to friendship convention [. . .] the lady fell in love with the messenger".[14] Leishman also calls her a "bad angel who has tempted away that good angel his friend".[15]

Slave imagery

Critics note that throughout Sonnet 133, Shakespeare uses slave imagery as a metaphor for the relationship between the speaker and the Dark Lady. The implication of the speaker as subservient to the dark lady is quite prevalent in the themes of traditional courtly love. The relationship is expressed throughout the sonnet with the use of words like "torture", "slave", "torment", "prison", and "jail". Critic Stephen Booth holds that the metaphor within this sonnet is "so complete, so urgent, so detailed… that the lovers and their situation, and their behavior becomes grotesque".[16] Booth proceeds to note that, although the slave imagery is a commonly used metaphor, the wording of the speaker's metaphors creates a witty and unconventional depiction of his relationship with the unknown woman. Through phrases such as "pent in thee" found in line 13, the reader is exposed to the image of the speaker imprisoned in the Dark Lady. Furthermore, in line 4 ("But slave to slavery my sweet'st friend must be?") we see the speaker playing on the hyperbole "by which lovers swore themselves their ladies' willing slave".[17] Essentially, Booth points out that although the speaker conforms with the traditional "slave" metaphor, he appears to almost resent his place in a relationship that is ultimately debilitating.

Scholarly critic Gertrude Garrigues argues that Shakespeare's use of slave imagery is simply symbolic of man as a "slave of the senses".[18] Garrigues counters Booth's argument in her assertion that the speaker is simply a slave to his own feelings and not a slave to the dark lady. Despite the speaker's great affliction over his relationship with the dark lady, he has willingly subjected himself to such unbearable torment. In relationship to this argument, it can be argued that the "friend" within Shakespeare's Sonnet 133 is in fact representative of the speaker's inner self. This strengthens Garrigues' argument, most notably in the line 4 where the speaker states, "But slavery to slavery my sweet'st friend must be?" When read in light of Garrigues' assertions, the reader can see that the speaker is referring to being enslaved by himself, or his senses.

References

- Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- Roberts, Josephine. ""Thou Maist Have Thy Will": The Sonnets of Shakespeare and His Stepsisters." Shakespeare Quarterly. Jan. 1996. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/pss/2870954 . Oct. 2010.

- Rowse, A.L. Shakespeare's Sonnets: The Problems Solved. New York: Harper and Row, 1973

- Booth 2000, p. 463.

- Vendler, Helen. The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1997

- Vendler, Helen. The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. Shakespeare Sonnets. New Haven: Yale UP, 1977.

- Vendler, Helen. The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. Shakespeare's Sonnets With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Cranbury, NJ: Rosemont Publishing & Printing Corp., 2007

- Fineman, Joel. Shakespeare's Perjured Eye: the Invention of Poetic Subjectivity in the Sonnets. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986

- Fineman, Joel. Shakespeare's Perjured Eye: the Invention of Poetic Subjectivity in the Sonnets. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986

- Leishman, J. B. Themes and Variations in Shakespeare's Sonnets. New York: Hutchinson & Co., 1961.

- Pequigney, Joseph. Such is My Love: A Study of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1985

- Mills, Laurens J. One Soul in Bodies Twain: Friendship in Tutor Literature and Stuart Drama. Bloomington: Principia Press, 1937

- Leishman, J. B. Themes and Variations in Shakespeare's Sonnets. New York: Hutchinson & Co., 1961

- Booth, Stephen, ed. Shakespeare Sonnets. New Haven: Yale UP, 1977.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. Shakespeare Sonnets. New Haven: Yale UP, 1977.

- Garrigues, Gertrude. "Shakespeare's "Sonnets" The Journal of Speculative Philosophy, July 1887. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/pss/25668140 Oct. 2010.

Further reading

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.