Sonnet 59

Sonnet 59 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It's a part of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young man.

| Sonnet 59 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

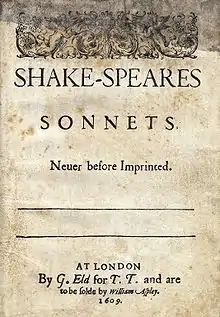

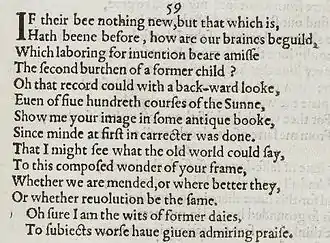

Sonnet 59 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Structure

Sonnet 59 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The Shakespearean sonnet contains three quatrains followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the form's typical rhyme scheme, ABAB CDCD EFEF GG, and is written a type of poetic metre called iambic pentameter based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The first line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / If there be nothing new, but that which is (59.1)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

The ninth line exhibits the rightward movement of the third ictus (resulting in a four-position figure, × × / /, sometimes referred to as a minor ionic):

× / × / × × / / × / That I might see what the old world could say (59.9)

The meter demands several variant pronunciations: In line three "labouring" has two syllables; in line five "recórd" although signifying the noun we pronounce "récord"; in line six "even" has one syllable; in line seven "ántique"; in line 10 "composed" has three syllables; in line 11 "whether" has one like the following "where" (which may or may not be an alternate spelling of the same word), although "whether" in the next line has the usual two syllables; in line 14 "given" has one syllable.

Themes and motifs

One story

In his book, How to Read Literature Like a Professor, Thomas Foster asserts that "pure originality is impossible".[2] Human beings are fascinated by life in space and time, so when we write about "ourselves" and "what it means to be human", we are really just writing the story of life.[3] Foster dedicates an entire chapter to Shakespeare's influence:

If you look at any literary period between the eighteenth and twenty-first centuries, you'll be amazed by the dominance of the Bard. He's everywhere, in every literary form you can think of. And he's never the same: every age and every writer reinvents its own Shakespeare.[4]

With each rewriting of this "story of life" the author is influenced by changes in attitudes and cultures between the original and current era of creation. Each author alters the message to fit their own views while the audience is a variable agency in the making of an interpretation. All of these same old factors help create a new story. The fear expressed in line 1–2, "If there be nothing new, but that which is Hath been before, how are our brains beguiled", is remedied by the strength of Shakespeare's own "invention" and its ability to influence future ages.[5]

Sonnets-body of work

In David Klein's analysis entitled Foreign Influence on Shakespeare's Sonnets, sonnet writing became a popular pastime during Shakespeare's time period:

[An] estimated … two hundred thousand sonnets were written in Europe between 1530 and 1650. The topic of most of them was love. Remembering that the subject of love was not limited to the sonnet form, we are prepared to expect a monotony of sentiment.[6]

The fear of a "second burden of a former child"[7] can be seen through Klein's analysis of sonnet writers of the period in general when compared to Shakespeare:

Their eyes were turned to the past where they saw a linguistic ideal they strove to imitate. … Such a mighty genius as Shakespeare, however, took what the Renascence had to offer him as useful material; and then, with face forward, set to work to create.[8]

Love was a conceit made petty by the sonnet writer stuck in revolution around one archetypal subject.[9] The writer's world was that subject and the world was there to profess the supremacy of her beauty. According to Klein, this takes the subject into the realm of imagination.[10] Shakespeare grounds his subject in reality using the following lines of Sonnet 59:

O, that record could with a backward look,

Even of five hundred courses of the Sun,

Show me your image in some antique book,

Since mind at first in character was done!

That I might see what the old world could say

To this composed wonder of your frame.[11]

Shakespeare uses his own education about the past to coolly reason his subject's beauty out of emotional speculation. In essence he has researched the beauty of antiquity and found:

O, sure I am, the wits of former days

To subjects worse have given admiring praise.[12]

Substantiation of beauty was a result of the Renaissance according to Klein. This accomplishment was rendered by "the revelation of man to himself, and he discovered that he had a body of which he could be as proud as of his mind, and which was just as essential to his being."[13]

Mind and body, form and feeling, flesh and thought

In the book Bodies and Selves in Early Modern England, Mike Schoenfeldt examines the concepts of physiology and inwardness as seen through the works of Shakespeare, specifically in The Sonnets. Through Schoenfeldt's literary research, he reveals the interaction between "flesh and thought" during Shakespeare's time period.[14] The dynamic that Shakespeare plays with in the "feeling" and the "form" of the sonnet portrays a "feeling in the form". He uses both the physical form and symbolic meaning of the sonnet art form.[15] "Since mind at first in character was done"[16] and "To this composed wonder of your frame."[17] According to Schoenfeldt, Shakespeare's writing is trying to "wring meaning from the matter of existence". [18] He is using both the physical "frame" and symbolic "mind" to convey his message.

Again, in the book The Body Emblazoned, by Jonathon Sawday, Shakespeare's sonnets are used to exhibit the idea of confrontation between the physical and the psychological human being. The conflict for early Renaissance writers involved the interaction between the "material reality" and the "abstract idea" of the body.[19] The conceptual framework of the period was starting to dissect the material from the immaterial; the subject from the object.[20] This idea is commonly referred to as the body and soul or mind and body conflict. Shakespeare is not exempt from this cultural ideology. In fact, his writing reflects a bodily interiority that was changing with new discoveries in science and art. According to Schoenfeldt:

By urging a particular organic account of inwardness and individuality, Galenic medical theory gave poets a language of inner emotion… composed of the very stuff of being. The texts we will be examining [including Shakespeare's sonnets] emerge from a historical moment when the "scientific" language of analysis had not yet been separated from the sensory language of experience… the Galenic regime of the humoral self that supplies these writers with much of their vocabulary of inwardness demanded invasion of social and psychological realms by biological and environmental processes.[21]

The outside world of the physical body is a part of the language in use by Shakespeare and his peers to portray the inward world of emotion and thought. Characters are the "vehicles" for meaning much as the body is the "vehicle" for the mind. "Since mind at first in character was done."[22] Yet, Shakespeare blurs the threshold between the two concepts of body and mind. "Which, labouring for invention, bear amiss The second burden of a former child!"[23]

The process of creation in the mind becomes the physical process of labor. Shakespeare's work takes on a life of its own literally, but here the reference is based on the cultural concept of psychological inwardness. "Shakespeare turns so frequently to physiological terminology because the job of the doctor, like that of the playwright and poet, is to intuit inner reality via external demeanor."[24] The fields of medicine and art merge in expression to create a common language of the self.

Birth and pregnancy

Pauline Kieman argues that the first quatrain in Sonnet 59 deals primarily with the theme of biological birth and pregnancy. She makes many claims supporting this idea, but the main points are as follows: 1. Invention becomes an image of pregnancy, and imaginative creation is now the dominating sense of invention so that we are made to imagine an embryo growing in the womb. 2. At line 4 the sense of the pain of a heavily pregnant womb is doubled by the word "second." 3. The poet tries to bring something into being for the first time, but before it can get born it is crushed under the weight of previous creations ("which for labouring invention bear amiss").[25]

Joel Fineman also subscribes to the theory of pregnancy and birth being a theme of the Sonnet, particularly the first quatrain, but he takes a different approach in his final analysis of this theme. He suggests that this rebirth is not a biological rebirth, but rather a rebirth of subjectivity, particularly within the Late Renaissance. So, in other words, the rebirth is not literal, as stated by Kieman, but rather the rebirth is symbolic of the sentiments and intellectual themes of the Late Renaissance. There is still a theme of birth, pregnancy, or rebirth, it is just concluded in different terms.[26]

Reflexivity

Alfred Harbage analyzes Shakespeare's "sense of history" as he puts it. This definitely centers itself on the idea of reflexivity, especially at the beginning of the poem, where Shakespeare shows the "baggage" that he enters his writing with.[27]

Murray Krieger affirms this idea that Shakespeare has a sense of history when he writes his sonnets, as though he believes that there is "nothing new" and everything, no matter how striking or unique, has happened before. He also states about the final line – "Or revolution be the same" – that,"a change that transforms history is always threatened with the grudging concession that it has happened before, with as much ardor, and in just this way."[28]

The young man

Russell Fraser suggests that Shakespeare's "if" clause which occurs in "if there be nothing new..." actually is referring to something new beneath the sun, namely, the young man. He also states that Shakespeare reverses his claim, but his main purpose is inclusiveness, wherein lies power.[29]

Blazon, competition

The popular aspect of the Petrarchan-style sonnet is called the blazon. The blazon divides the unobtainable female object of desire into parts that can be compared to the outside world. According to Sawday, "the free-flow of language within the blazon form over the female body was not a celebration of 'beauty' (the ostensible subject), but of male competition."[30] "O, sure I am the wits of former days / To subjects worse have given admiring praise."[31] Shakespeare uses the blazon for the evaluation of the sonnet itself, drawing attention to this competition.

Difference and violence

The idea of identity commands a differentiation between the self and society. According to René Girard, in his book Violence and the Sacred:

It is not the differences but the loss of them that gives rise to violence and chaos... The loss forces men into a perpetual confrontation, one that strips them of all their distinctive characteristics – in short, of their "identities." Language itself is put in jeopardy. 'Each thing meets/ In mere oppugnancy:' the adversaries are reduced to indefinite objects, "things" that wantonly collide with each other like loose cargo on the decks of a storm-tossed ship. The metaphor of the floodtide that transforms the earth's surface to a muddy mass is frequently employed by Shakespeare to designate the undifferentiated state of the world that is also portrayed in Genesis.[32]

Girard goes on to say that "equilibrium invariably leads to violence," while justice is really the imbalance that shows the difference between "good" and "evil" or "pure" and "impure." When the past is not differentiable from the present, a violence called sacrificial crises occurs. There will always be differences despite the seeming similarities; otherwise, violence will ensue to "correct" the situation.[32] This experience in poetry is also referred to as a "force, as it were, 'behind' the representative surface of the poetry."[33] The physical is again seen as part of the psychology used by Shakespeare in the language of his sonnets.

Biblical allusions

Much of the sonnet seems to be focused on a debate as to whether the old style or the new is superior. In fact, the opening lines stating that "If there be nothing new, but that which is Hath been before…" call to mind a similar passage from the Bible's Book of Ecclesiastes, chapter 1, verse 9: "The thing that hath been is that which shall be; and that which hath been done is that which shall be done; and there is no new thing under the sun."

The speaker asks whether the Fair Youth has surpassed his ancient equivalents, or whether he has fallen short of their legacy. This is summarized in lines 11 and 12:

Whether we are mended, or whe'er better they,

Or whether revolution be the same

Ultimately, the speaker decides that even if the Youth has not out-shined his predecessors, he is still certainly more beautiful than at least some who came before him, as the speaker states in lines 13 and 14: "O, sure I am, the wits of former days / To subjects worse have given admiring praise."

Notes and references

Notes

- Pooler 1918, p. 61.

- Foster 2003, p. 187.

- Foster 2003, p. 186.

- Foster 2003, p. 38.

- Foster 2003, p. 44.

- Klein 1905, p. 457.

- Sonnet 59, Line 4

- Klein 1905, p. 472.

- Klein 1905, p. 470.

- Klein 1905, p. 471.

- Sonnet 59, Lines 5-10

- Sonnet 59, Lines 13-14

- Klein 1905, p. 463.

- Schoenfeldt 2000, p. 77.

- Schoenfeldt 2000, p. 76.

- Sonnet 59, Line 8

- Sonnet 59, Line 10

- Schoenfeldt 2000, p. 172.

- Sawday 1996, p. 3.

- Sawday 1996, p. 20.

- Schoenfeldt 2000, p. 8.

- Sonnet 59, Line 8

- Sonnet 59, Lines 2-4

- Schoenfeldt 2000, p. 75.

- Kiernan 1995.

- Fineman 1984.

- Harbage 1961.

- Krieger 1986.

- Fraser 1989.

- Sawday 1996, p. 199.

- Sonnet 59, Lines 13-14

- Girard 1977, p. 51.

- Clody 2008.

References

- Clody, Michael (2008). "Shakespeare's "Alien Pen": Self-Substantial Poetics in the Young Man Sonnets". Criticism. Wayne State University Press. 50 (3): 471–99. eISSN 1536-0342. ISSN 0011-1589. JSTOR 23130889 – via JSTOR.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fineman, Joel (1984). "Shakespeare's "Perjur'd Eye"". Representations. University of California Press (7): 59–86. doi:10.2307/2928456. eISSN 1533-855X. ISSN 0734-6018. JSTOR 2928456 – via JSTOR.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Foster, Thomas C. (2003). How to Read Literature Like a Professor. New York: Harper. ISBN 0-06-000942-X. OCLC 50511079.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fraser, Russell (1989). "Shakespeare at Sonnets". The Sewanee Review. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 97 (3): 408–27. eISSN 1934-421X. ISSN 0037-3052. JSTOR 27546084 – via JSTOR.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Girard, René (1977) [1972 (French)]. La violence et le sacré [Violence and the Sacred] (in French). Translated by Gregory, Patrick. Editions Bernard Grasset / Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1472520814.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harbage, Alfred (1961). "The Sense of History in Greek and Shakespearean Drama by Tom F. Driver". Renaissance News. Renaissance Society of America. 14 (1): 32–3. doi:10.2307/2857232. hdl:2027/mdp.39015024853965. ISSN 0277-903X. JSTOR 2857232 – via JSTOR.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kiernan, Pauline (1995). "Death by Rhetorical Trope: Poetry Metamorphosed in Venus and Adonis and the Sonnets". The Review of English Studies. Oxford University Press. 46 (184): 475–501. doi:10.1093/res/XLVI.184.475. eISSN 1471-6968. ISSN 0034-6551. JSTOR 519060 – via JSTOR.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Klein, David (1905). "Foreign Influence on Shakespeare's Sonnets". The Sewanee Review. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 13 (4): 454–74. eISSN 1934-421X. ISSN 0037-3052. JSTOR 27530718 – via JSTOR.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Krieger, Murray (1986). "Literary Invention and the Impulse to Theoretical Change: 'Or Whether Revolution Be the Same'". New Literary History. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 18 (1, Studies in Historical Change): 191–208. doi:10.2307/468662. eISSN 1080-661X. ISSN 0028-6087. JSTOR 468662 – via JSTOR.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pooler, C. Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, 1st series. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sawday, Jonathan (1996). The Body Emblazoned: Dissection and the Human Body in Renaissance Culture. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415157193.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schoenfeldt, Michael C. (2000). Bodies and Selves in Early Modern England: Physiology and Inwardness in Spenser, Shakespeare, Herbert, and Milton. Cambridge Studies in Renaissance Literature and Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521630733.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

.png.webp)