Sonnet 36

Sonnet 36 is one of 154 Shakespeare's sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It's a member of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the speaker expresses his love towards a young man.

| Sonnet 36 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

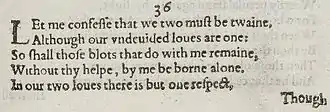

The first five lines of Sonnet 36 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

History

Sonnet 36 is just one of The Sonnets out of 154 that were written. There are 120 sonnets devoted to an unknown young man, twenty-eight sonnets are written to a young lady, and the rest are allegorical.[2] Sonnet 36 falls in the category of love and beauty along with other sonnets such as 29, 37, and many others according to Claes Schaar.[3]

Structure

Sonnet 36 is a typical English or Shakespearean sonnet, constructed from three quatrains and a final rhyming couplet. It follows the form's typical rhyme scheme, ABAB CDCD EFEF GG, and is written in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The second line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / Although our undivided loves are one: (36.2)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

Analysis of relationship between speaker and young man

Shakespeare most likely wrote the sonnets that were meant for the young man over a four- or five-year period.[4] There is speculation that the young man Shakespeare is addressing may be named William Hughs or Hews. While Butler raises the question of Shakespeare's homosexuality, other critics such as Wilde refute this claim and maintain Shakespeare had an innocent relationship with the boy. However, no reputable evidence for this theory has been found. Throughout his sonnets, Shakespeare addresses the young man's physical beauty as well as his internal beauty.[5] In this particular sonnet, Shakespeare admits his love for the young man, but he states that he is not able to publicly acknowledge his love due to the shame that might result. According to Lord Alfred Douglas, there seems to be a contradiction between Sonnet 35 and Sonnet 36, because while he rebukes the young man in the first sonnet, he admits his own guilt in the second.[6] Butler proposed that the young man in this poem was guilty of some public offense. However, Alfred Douglas believes that line 10 of the poem completely exonerates the young man of such an offense, because Shakespeare admits his own guilt.[6]

General analysis

Sonnet 36 represents the speaker's acceptance that he and his lover will no longer be able to be together. The two seem to both love each other, but due to some unknown incident (most likely caused by the speaker) they cannot be together. Because of this incident, embarrassment would be brought to both (especially the lover) if they were seen together in public. The message of the sonnet is best summed up when the speaker says, "I may not ever-more acknowledge thee, / Lest my bewailed guilt should do thee shame," (lines 9-10) implying that the young lover would be shamed if others knew he and the speaker knew each other.

Line by line analysis

Let me confess that we two must be twain, / Although our undivided loves are one:

- The speaker admits that the two of them cannot be together (twain = separate or parted) even though their loves are together and seem inseparable.[7]

So shall those blots that do with me remain, / Without thy help, by me be borne alone.

- "Blots" is a vague reference to some disgrace that the reader is unaware of. The speaker has accepted that he must be alone, because he sees no way they can be together.[7]

In our two loves there is but one respect, / Though in our lives a separable spite,

- When it comes to their compassion there is only one matter: love. But in reality, there is a "separable spite" that will keep them apart.[7]

Which, though it alter not love's sole effect, / Yet doth it steal sweet hours from love's delight.

- Although this "spite" cannot change the way the two feel about each other, It can still take away the time they can spend together, which is the most enjoyable part of love.[7]

I may not evermore acknowledge thee, / Lest my bewailed guilt should do thee shame,

- The speaker is proclaiming that he will no longer acknowledge the young lover in public. This is because he wants to avoid bringing further shame on the object of the poem via guilt by association, contrary to the reference cited.[7]

Nor thou with public kindness honour me, / Unless thou take that honour from thy name:

- The speaker is advising the young lover to not acknowledge him in public either. Unless the young lover wants to bring dishonor upon himself by further association with the speaker.[7]

But do not so; I love thee in such a sort, / As thou being mine, mine is thy good report.

- He is reinforcing the command to not acknowledge him and reminding him that he loves him since they are "one," if either is dishonored, then both are dishonored.[7]

According to Helen Vendler, author of The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets, there is a parallel of phrases in the same lines that represent unity and divisions respectively. For example, the phrase, "we two" is followed by, "must be twain", meaning must be separate. Also, "Our two loves" is followed by "separable spite".[8]

Criticism

Relationship between sonnet 36 and other sonnets

The location of where Sonnet 36 properly fits in the sequence of Shakespeare's sonnets has been widely debated. Claes Schaar groups the sonnets according to how similar they are. Sonnet 36 is grouped with Sonnet 33 through Sonnet 35. Although there is no apparent connection between Sonnet 36 and 37, there is an apparent link between the topic in 35 and the first line of 36.[9] Helen Vendler agrees with Schaar contending that Sonnets 37 and 38 seem to not fit in place between Sonnets 36 and 39. He claims Sonnet 36 and 39 are often linked because they share three sets of rhymes: me/thee, one/alone, and twain/remain. Sonnets 36 and 39 both contain the word "undivided" and concern a thematic commonality concerning the separation of lovers. Sonnets 37 and 38 are linked with Sonnet 6 in both material and the use of the phrase "ten times" thus, illustrating discontinuity among the sonnets. Sonnet 36 is also strongly linked with Sonnet 96 in that the rhyming couplet is identical, "But do not so, I love thee in such sort, As thou being mine, mine is thy good report." The theme of depriving oneself of honor for the other is also consistent between the two. These discrepancies with thematic links and common word usage have given legitimacy to the argument that the Sonnets may not be in a finalized order.[8] It is argued that Shakespeare provided room among his clearly written sonnets for some of his earlier and less refined sonnets. Therefore, the order of the sonnets may not be the polished repertoire Shakespeare had intended.[8]

Biblical references

Blackmore Evans suggested that Sonnet 36 was influenced by Ephesians 5:25-33, "Husbands, love your wives, just as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her to make her holy, cleansing her by the washing with water through the word, and to present her to himself as a radiant church, without stain or wrinkle or any other blemish, but holy and blameless. In this same way, husbands ought to love their wives as their own bodies. He who loves his wife loves himself. After all, no one ever hated his own body, but he feeds and cares for it, just as Christ does the church— for we are members of his body. 'For this reason a man will leave his father and mother and be united to his wife, and the two will become one flesh.' This is a profound mystery—but I am talking about Christ and the church. However, each one of you also must love his wife as he loves himself, and the wife must respect her husband." Most particularly, verses 31 and 32 that discuss the mystery of the two, husband and wife, becoming "one flesh" in marriage. This link is most strongly exemplified in the first two lines of Sonnet 36, "Let me confess that we two must be twain, Although our undivided loves are one:"[7] Stephen Booth adds that Ephesians 5 was a regular source of inspiration for Shakespeare. There is also evidence of Ephesians 5 in Shakespeares, Henry IV, Part 1. Booth suggests that the "blots" in line 3 of Sonnet 36 may be an allusion to Eph 5:27, "...without stain or wrinkle or any other blemish..." There is also a parallel in motivation between the speaker's self-sacrifice in accepting separation for his lover's sake and Christ's marriage to the church.[10]

Other references

Line 12 of Sonnet 36 suggests that Shakespeare may be addressing a person of nobility. The correct address of such a person was, "Right honourable". Such parallels in dedications can be found in Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece.[7]

In Music

Poeterra recorded a pop ballad version of Sonnet 36 on their album "When in Disgrace" (2014).

Notes

- Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- Douglas (1933). p. 17.

- Schaar (1962). p. 187.

- Hubler (1952). p. 78.

- Douglas (1933). pp. 16-17, 19.

- Douglas (1933). pp. 90-91.

- Evans (2006).

- Vendler (1997).

- Schaar (1962)

- Booth (1977).

References

- Atkins, Carl D. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets with Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Rosemont, Madison.

- Baldwin, T. W. (1950). On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

- Douglas, Alfred (1933). The True History of Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Kennikat Press, New York.

- Hubler, Edwin (1952). The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Knights, L. C. (1967). Shakespeare's Sonnets: Elizabethan Poetry. Paul Alpers. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Matz, Robert (2008). The World of Shakespeare's Sonnets: An Introduction. Jefferson, N.C., McFarland & Co..

- Schaar, Cales (1962). Elizabethan Sonnet Themes and the Dating of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Hakan Ohlssons Boktryckeri, Lund.

- Schoenfeldt, Michael (2007). The Sonnets: The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare's Poetry. Patrick Cheney, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

.png.webp)