Sonnet 77

Shakespeare's 77th sonnet is the half-way point of the book of 154 sonnets. The poet here presents the idea of the young man taking on the role of poet and writing about himself. This sonnet makes use of the rhetorical device termed correlatio, which involves a listing and correlating of significant objects, and which was perhaps overused in English sonnets. The objects here are a mirror, a time piece and a notebook, each representing a way towards self-improvement for the young man as poet.[2][3]

| Sonnet 77 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

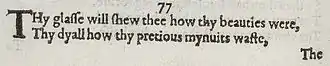

The first two lines of Sonnet 77 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Paraphrase

When you look in your mirror, you will see how you are aging. Your timepiece will show you how your minutes are being wasted. This book will allow you to record the impressions of your mind, and these impressions will themselves teach you. The lines in your face that your mirror shows you will remind you of the open mouths of fresh graves. The hands of the dial will truly teach you how time thievishly keeps leading towards eternity. What your memory cannot keep, you should write down, and when you return to them you will find that they are like well-nursed children born of your brain, and you will meet them again afresh—like new friends. The oftener you do these duties – observing, contemplating, writing − the more "your book" will profit.

Structure

Sonnet 77 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet contains three quatrains, followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the rhyme scheme ABAB CDCD EFEF GG, and is composed in iambic pentameter lines, a type of poetic metre in which each line as five feet, each foot has two syllables, and each syllable is accented weak/strong. Most of the lines are regular iambic pentameter including the first:

× / × / × / × / × / Thy glass will show thee how thy beauties wear

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

Source and analysis

The poem begins with the act of looking in a mirror, and the act of noticing the passage of time – which operate exactly as a memento mori: the medieval tradition of contemplating one's own mortality. The poem turns from that and ends with a model of creative productivity through observation, contemplation and writing — in a collaboration of the poet's offices and the mind's imprint on the young man.[4]

George Steevens and Edmond Malone consider the poem may be referring to the gift of a blank-book or book of tablets, perhaps given to the young man. Edward Dowden hypothesized that the poem relates to the Rival Poet: knowing that he has lost favor, the speaker makes a present of this blank book to the youth, who will now have to fill it himself, since the speaker has fallen silent.

It has been suggested that the mirror and dial referred to may be devices represented on the cover of the book – assuming the book is an actual object. Alternately, as Rolfe hypothesized, they might have been gifts enclosed with the book. Henry Charles Beeching discounts any clear biographical clue in the poem, arguing that it is so unrelated to those next it in the sequence that it must be read apart.

Sonnet 77, together with the sonnet that precedes it, and the sonnet that follows it form a group, in which the poet's thoughts turn to the act of writing. In sonnet 76 the poet fears his writing may be old-fashioned; in sonnet 77 he demonstrates both the problem and his fears by having sonnet 77 take the form of the much maligned rhetorical device correlatio, which was perhaps over-used by Philip Sidney in the 1590s, then later in that decade mocked by Sir John Davies in his Gullinge Sonnets. Finally in sonnet 78 the poet has found a solution to the problem and the right way forward.[5]

The quarto's first line uses a common variant spelling for wear: were. This spelling may suggest: how thy beauties “used to be”. But Booth considers that potential second meaning to be not useful or meaningful here.[6]

The three objects – the glass, the dial, and the book – may be purely metaphorical, not references to actual objects, but metaphors for observation, time and the act of writing.

Sonnet 77 is the midpoint in the sequence of 154 sonnets. The fact that it is about a mirror may be relevant to its placing. Edmund Spenser mentions mirrors at the midpoint of his sequence, Amoretti, Sonnet 45 of 89: "Leaue lady in your glasse of christall clene, / Your goodly selfe for euermore to vew".[7]

The original quarto's "blacks" in line 10 is usually emended to "blanks", following Alexander Dyce. Some critics have defended "blacks" as referring to printer's type, or to slate notebooks. If it refers to printers type it allows the reference to the quarto itself as a gift to the young man.

References

- Shakespeare, William. Duncan-Jones, Katherine. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Bloomsbury Arden 2010. p. 265 ISBN 9781408017975.

- Kalax, Rayna. Frame, Glass, Verse: The Technology of Poetic Invention in the English Renaissance. Cornell University Press, 2007. ISBN 9780801445415 p. 128

- Shakespeare, William. Duncan-Jones, Katherine. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Bloomsbury Arden 2010. p. 264 ISBN 9781408017975.

- Kalas, Rayna. Frame, Glass, Verse: The Technology of Poetic Invention in the English Renaissance. Cornell University Press, 2007. p. 128 ISBN 9780801445415

- Kalas, Rayna. Frame, Glass, Verse: The Technology of Poetic Invention in the English Renaissance. Cornell University Press, 2007. p. 128 ISBN 9780801445415

- Booth, Stephen. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Yale University Press. 2000. ISBN 9780300085068 p. 266

- Larsen, Kenneth J. "Structure" in Essays on Shakespeare's Sonnets.

Further reading

- First edition and facsimile

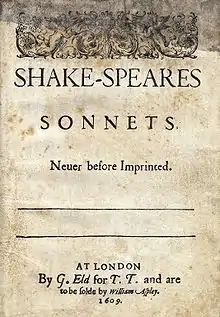

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

.png.webp)