Sonnet 29

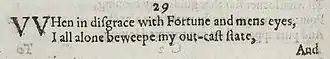

Sonnet 29 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is part of the Fair Youth sequence (which comprises sonnets 1-126 in the accepted numbering stemming from the first edition in 1609). In the sonnet, the speaker bemoans his status as an outcast and failure but feels better upon thinking of his beloved. Sonnet 29 is written in the typical Shakespearean sonnet form, having 14 lines of iambic pentameter ending in a rhymed couplet.

| Sonnet 29 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The first two lines of Sonnet 29 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Structure

Sonnet 29 follows the same basic structure as Shakespeare's other sonnets, containing fourteen lines and written in iambic pentameter, and composed of three rhyming quatrains with a rhyming couplet at the end. It follows the traditional English rhyme scheme of abab cdcd efef gg — though in this sonnet the b and f rhymes happen to be identical. As noted by Bernhard Frank, Sonnet 29 includes two distinct sections with the Speaker explaining his current depressed state of mind in the first octave and then conjuring what appears to be a happier image in the last sestet.[2]

Murdo William McRae notes two characteristics of the internal structure of Sonnet 29 he believes distinguish it from any of Shakespeare's other sonnets.[3] The first unique characteristic is the lack of a "when/then" pattern. Traditionally, the first eight lines of a sonnet produce a problem (a "when" statement) that is then resolved in the last six lines (a "then" statement). McRae points out, however, that the Speaker in this sonnet fails to produce a solution possibly because his overwhelming lack of self-worth prevents him from ever being able to state an actual argument, and instead uses his conclusion to contrast the negative feelings stated in the previous octave. McRae notes that this break from the traditional style of sonnet writing creates a feeling of the sonnet being "pulled apart". The second unique characteristic is the repetition of the b-rhyme in lines 2 and 4 ("state" and "fate") as well as 10 and 12 ("state" and "gate"). McRae says that the duplication of the b-rhyme redirects the reader's attention to the lines, and this "poem within a poem" pulls the piece back together in a way that contrasts its original pulling apart.

However, Shakespeare did not only create a pattern of line rhymes. As Frank explains in his article Shakespeare repeats the word "state" three times throughout the poem with each being a reference to something different. The first "state" referring to the Speaker's condition (line 2), the second to his mindset (line 10), and the third to "state" of a monarch or kingdom (line 14).

This issue of the duplicated b-rhyme is addressed in other sources as well. Philip McGuire states in his article that some refer to this as a "serious technical blemish", while others maintain that "the double use of 'state' as a rhyme may be justified, in order to bring out the stark contrast between the Speaker's apparently outcast state and the state of joy described in the third quatrain".[4]

Paul Ramsey points out the line three specifically as "one of the most perturbed lines in our language".[5] He specifically points out stressed syllables, "troub-", "deaf", and "heav'n", saying they are "jarringly close together" and that "the 'heav'n with' is probably the most violent example in the sonnets of a trochee without a preceding verse-pause... The heaping of stress, the harsh reversal, the rush to a vivid stress — all enforce the angry anti-religious troubled cry".[6]

It is convenient to scan the first four lines:

/ × × / × / × × / / When in disgrace with Fortune and men's eyes, × / × / × / × / × / I all alone beweep my outcast state, × / × / / × × / × / And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries, × / × / × / × / × / And look upon myself and curse my fate, (29.1-4)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

Lines two and four are metrically regular, but alternate with lines (one and three) which are more metrically complex, a tendency that continues throughout the poem[7]

The first line has an initial reversal, and concludes with the fourth ictus moving to the right (resulting in a four-position figure, × × / /, sometimes referred to as a minor ionic).

While the third line's rhythm is unusual, it is not in itself (pace Ramsey) apocalyptic; line six of Sonnet 7 exhibits precisely the same rhythm under much tamer circumstances.

Both "deaf" and "heaven" (here scanned as one syllable) have tonic stress, but that of "deaf" is normally subordinated to that of "heaven", allowing them comfortably to fill odd/even positions, but not even/odd. A reversal of the third ictus (as shown above) is normally preceded by at least a slight intonational break, which "deaf heaven" does not allow. Peter Groves calls this a "harsh mapping", and recommends that in performance "the best thing to do is to prolong the subordinated S-syllable [here, "deaf"] ... the effect of this is to throw a degree of emphasis on it".[8]

Speaker and subject

Camille Paglia states that there is nothing in the poem that would provide a clue as to whether the poem is directed towards a man or a woman, but assumes, as many do, that Sonnet 29 was written about the young man.[9] Both Paglia and Frank agree that the first octave is about the Speaker's current depression caused by his social ostracism in his "outcast state" (line 2) and personal misfortune that has "curse[d] my fate" (line 4). The Speaker proclaims his jealousy of those that are "rich in hope" (line 5) and "with friends possess'd" (line 6), once again referring to his hopelessness and low social status. Paglia refers to this section of the poem as a "list of half-imaginary grievances." Frank seems to agree with her statement of "half imaginary" since he believes the Speaker wills his own misery.

As the poem moves from the octave to the sestet, Frank makes note of the Speaker's "radical movement from despair to alert". This sudden emotional jump (along with the pattern of the "state") displays the Speaker's "wild mood swings". Frank believes that the last sestet, however, is not as "happy" as some may believe. Using line 10 as his example, Frank points out that the Speaker says he simply "thinks" of his beloved while he is alone which leads one to wonder if the said "sweet love" (line 13) even knows the Speaker exists.

Paglia, however, takes several different views on the poem. For example, she does not actually come out and accuse the Speaker of causing his own suffering. Referencing line 1, she notes that Fortune (personified) has actually abandoned the poor Speaker. This abandonment is the cause of the Speaker's desire for "this man's art, and that man's scope" (line 7) and has caused the Speaker to only be "contented" (line 8) which hints at the Speaker's (and possibly Shakespeare's) lack of artistic inspiration. The final few lines, however, are where Paglia differs the most from Frank. Paglia feels that the "love" of the Speaker's has been restored and that he has received a "spiritual wealth". The once jealous and desperate Speaker has now found solace in love knowing that love "dims all material things". Elizabeth Harris Sagaser sets Sonnet 29 apart from other Elizabethan sonnets in that the speaker is the main focus, as opposed to many love sonnets of the time focused entirely on the object of the speaker's affection, or so of the poet's desire; this would seem that the poem is about the woman, not the speaker. However, Sasager says, "I do not mean to imply that... (these poems) are themselves 'about' particular beloveds. But they do pretend to be, and therein is the difference.[10] She goes on to clarify this difference, or what sets sonnet 29 apart from most love object-centered sonnets of the time. "The poet-lover in sonnet 29 admits up front that the fruits of his inward experience are primarily his own, though not his own in terms of everafter fame... Instead, the speaker of 29 is concerned first to wonder" [11] This is to say that though most poetry of the time was at least disguised to be about the object of the speaker's affection, this sonnet does not even attempt to do so. According to Sasager, it is clear that this poem is speaker-focused and about the emotions and experiences of the speaker, not that of the beloved. As discussed by other critics, Sasager addresses the lack of "when... then" structure saying "the poem shifts to representing a particular moment: not a past moment, but now." She makes a point to say this differs notably from other poems of the time.

Religious nature

Paglia and Frank have similar views on the religious references made throughout the poem. The Speaker first states that heaven is deaf to his "bootless [useless] cries" (line 3). The "lark at break of day arising" (line 11) symbolizes the Speaker's rebirth to a life where he can now sing "hymns at heaven's gate" (line 12). This creates another contrast in the poem. The once deaf heaven that caused the Speaker's prayers to be unanswered is now suddenly able to hear. Both authors note the lack of any reference to God and how the Speaker instead speaks only of heaven.

Expanding on that notion, Paul Ramsey claims: "Sonnet 29 says that God disappoints and that the young man redeems".[12] This is to say that the poem is not religious in the institutional way, but rather it is its own kind of religion. Ramsey continues, "Against that heaven, against God, is set the happy heaven where the lark sings hymns. The poem is a hymn, celebrating a truth declared superior to religion."[13] So while Sonnet 29 makes some religious references, Ramsey maintains that these are in fact anti-religious in sentiment.

In poetry and popular culture

- The "turn" at the beginning of the third quatrain occurs when the poet by chance ("haply") happens to think upon the young man to whom the poem is addressed, which makes him assume a more optimistic view of his own life. The speaker likens such a change in mood "to the lark at break of day arising, From sullen earth, sings hymns at heaven's gate". This expression was most probably the inspiration for American poet Wallace Stevens when he wrote the poem The Worms at Heaven's Gate in Harmonium.

- T.S. Eliot quotes this sonnet in his 1930 poem "Ash Wednesday": "Because I do not hope / Because I do not hope to turn / Desiring this man's gift and that man's scope / I no longer strive to strive towards such things / (Why should the agèd eagle stretch its wings?)"

- Featured in the 1950 film In a Lonely Place when Charlie Watterman, portrayed by Robert Warwick recites the sonnet to an exhausted Dixon Steele, played by Humphrey Bogart.

- The sonnet's first line was the inspiration for the title of John Herbert's 1967 play Fortune and Men's Eyes. The play was adapted into a film of the same name in 1971.

- In episode 3 ("Siege") from season 1 of Beauty and the Beast, Vincent (portrayed by Ron Perlman) reads this sonnet to Catherine (played by Linda Hamilton)

- In season 2 ("The Measure of a Man") of Star Trek: The Next Generation, Cmdr. Bruce Maddox reads the first two lines of the sonnet out of Lt. Cmdr. Data's Shakespeare book

- Edward Lewis, portrayed by Richard Gere, reads this sonnet to Vivian Ward, played by Julia Roberts, during their scene at the park in Pretty Woman

- Featured in the 2002 film Conviction where Omar Epps, portraying an imprisoned Carl Upchurch, reads the first half of the sonnet aloud to other prisoners from his cell.

- The black metal group Deafheaven derived its name from this sonnet.[14]

- In the Netflix show Dear White People, the character Lionel uses the password "Sonnet 29" to gain entry to a house party hosted by theater students.

- Canadian singer and composer Rufus Wainwright musicalized the poem in the song of the same name (Sonnet 29). The song appears on his 2016 album "Take All My Loves: 9 Shakespeare Sonnets" and features British singer Florence Welch on leading vocals. The track before that is a reading of the Sonnet done by Carrie Fisher.

- In 2014 Poeterra released a pop rock version of this poem on their album "When in Disgrace" (2014).[15]

- The X-Files' Cigarette Smoking Man (played by William B. Davis) first line in the second episode of the seventh season ("The Sixth Extinction II: Amor Fati") is the first line of this sonnet

- The Netflix Coen Brothers anthology western The Ballad of Buster Scruggs features this sonnet in its third instalment ("Meal Ticket").

- In Big City Greens ("Wishing Well"), when Cricket's shoulder angel and shoulder devil fight inside his brain, Cricket suddenly bursts into the first two lines of the sonnet in a regal voice.

Notes

- Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- Bernhard Frank, "Shakespeare's 'SONNET 29'", The Explicator Volume 64 No. 3 (2006): p. 136-137.

- Murdo William McRae, "Shakespeare's Sonnet 29", The Explicator Volume 46 (1987): p. 6-8

- McGuire, Philip C., "Shakespeare's Non-Shakespearean Sonnets." Shakespeare Quarterly 38.3 (1987): 304-19. JSTOR. Web.

- Ramsey, Paul. The Fickle Glass: A Study of Shakespeare's Sonnets. New York: AMS, 1979. Print. pg: 152-153

- Ramsey, p. 153

- Wright, George T. (1988). Shakespeare's Metrical Art. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 80. ISBN 0-520-07642-7.

- Groves, Peter (2013). Rhythm and Meaning in Shakespeare: A Guide for Readers and Actors. Melbourne: Monash University Publishing. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-1-921867-81-1.

- Camille Paglia, Break Blow Burn. New York: Pantheon Books, 2005, p. 8-11 ISBN 0375420843.

- Sasager, Elizabeth H. "Shakespeare's Sweet Leaves: Mourning, Pleasure, and the Triumph of Thought in the Renaissance Love Lyric," English Literary History, The Johns Hopkins University Press 61.1 (1994): 1-26. JSTOR. Web. 27 Oct. 2009.<https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/2873429.pdf>, page 8

- Sasager, page 9.

- Ramsey, Paul. The Fickle Glass: A Study of Shakespeare's Sonnets. New York: AMS, 1979. Print. pg. 152

- Ramsey, page 153

- Miller, Robert (19 March 2012). "On the Record with Deafheaven". the dropp. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- "Poeterra - Shakespeare Sonnet 29 Song - Lyric Music Video".

References

- Baldwin, T. W. (1950). On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

- Hubler, Edwin (1952). The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Schoenfeldt, Michael (2007). "The Sonnets," The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare's Poetry. Patrick Cheney, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

External links

Works related to Sonnet 29 (Shakespeare) at Wikisource

Works related to Sonnet 29 (Shakespeare) at Wikisource- Paraphrase and analysis (Shakespeare-online)

.png.webp)