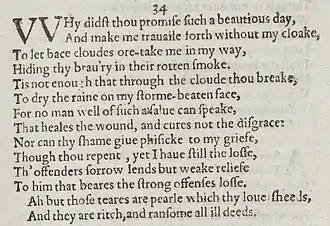

Sonnet 34

Shakespeare's Sonnet 34 is included in what is referred to as the Fair Youth sequence, and it is the second of a briefer sequence (Sonnet 33 through Sonnet 36) concerned with a betrayal of the poet committed by the young man, who is addressed as a personification of the sun.[1]

| Sonnet 34 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sonnet 34 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Structure

Sonnet 34 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet, composed of three quatrains and a final couplet. It follows the form's typical rhyme scheme: ABAB CDCD EFEF GG. It is written in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. Line 12 exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / To him that bears the strong offence's loss.

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

It is possible that for Shakespeare the couplet embodied a true rhyme (as indicated by the Quarto spelling: sheeds/deeds) even though seemingly the singular shed would not have made a true rhyme with deed.[2]

Source and analysis

Following Horace Davis, Stephen Booth notes the similarity of this poem in theme and imagery to Sonnet 120. Gerald Massey finds an analogue to lines 7–8 in The Faerie Queene, 2.1.20.

In 1768, Edward Capell altered line ten by replacing the word "loss" with the word "cross". This alteration was followed by Edmond Malone in 1783, and was generally accepted in the 19th and 20th Centuries. More recent editors do not favor this as a speculation that introduces a metaphor of the young man as a Christ figure, something that Shakespeare did not do here or elsewhere; the idea, as it would be portrayed by the young man in the context of this sonnet, does not fit well with Gospel accounts.[3] Stephen Booth considers that the repetition of the word suggests the persistence of "loss".[4][5]

Interpretations

- Robert Lindsay, for the 2002 compilation album, When Love Speaks (EMI Classics)

Notes

- Shakespeare, William. Duncan-Jones, Katherine. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Bloomsbury Arden 2010. p. 178 ISBN 9781408017975.

- Booth, Stephen (2000) [1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. New Haven: Yale Nota Bene [Yale University Press]. p. 189. ISBN 0-300-08506-0.

- Shakespeare, William. Duncan-Jones, Katherine. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Bloomsbury Arden 2010. p. 178 ISBN 9781408017975.

- Booth, Stephen. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Yale University Press. 1977. p. 189 ISBN 0-300-01959-9

- Hammond. The Reader and the Young Man Sonnets. Barnes & Noble. 1981. p. 44 & 229 ISBN 9781349054435

References

- Baldwin, T. W. (1950). On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

- Fineman, Joel (1984). Shakespeare's Perjur'd Eye: Representations. pp. 59–86.

- Hubler, Edwin (1952). The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Schoenfeldt, Michael (2007). The Sonnets: The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare's Poetry. Patrick Cheney, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

External links

Works related to Sonnet 34 at Wikisource

Works related to Sonnet 34 at Wikisource- Paraphrase and analysis (Shakespeare-online)

- Analysis

.png.webp)