Steller's sea cow

Steller's sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas) is an extinct sirenian described by Georg Wilhelm Steller in 1741. At that time, it was found only around the Commander Islands in the Bering Sea between Alaska and Russia; its range was more extensive during the Pleistocene epoch, and it is possible that the animal and humans previously interacted. Some 18th-century adults would have reached weights of 8–10 t (8.8–11.0 short tons) and lengths up to 9 m (30 ft).

| Steller's sea cow Temporal range: Pleistocene– C. E. 1768 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton at the Finnish Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Sirenia |

| Family: | Dugongidae |

| Genus: | †Hydrodamalis |

| Species: | †H. gigas |

| Binomial name | |

| †Hydrodamalis gigas Zimmermann, 1780 | |

| |

| Map showing the position of the Commander Islands to the east of Kamchatka. The larger island to the west is Bering Island; the smaller island to the east is Copper Island. | |

| Synonyms[2][3][4][5] | |

|

List of synonyms

| |

It was a part of the order Sirenia and a member of the family Dugongidae, of which its closest living relative, the 3 m (9.8 ft) long dugong (Dugong dugon), is the sole living member. It had a thicker layer of blubber than other members of the order, an adaptation to the cold waters of its environment. Its tail was forked, like that of whales or dugongs. Lacking true teeth, it had an array of white bristles on its upper lip and two keratinous plates within its mouth for chewing. It fed mainly on kelp, and communicated with sighs and snorting sounds. Evidence suggests it was a monogamous and social animal living in small family groups and raising its young, similar to modern sirenians.

Steller's sea cow was named after Georg Wilhelm Steller, who first encountered it on Vitus Bering's Great Northern Expedition when the crew became shipwrecked on Bering Island. Much of what is known about its behavior comes from Steller's observations on the island, documented in his posthumous publication On the Beasts of the Sea. Within 27 years of its discovery by Europeans, the slow-moving and easily-caught mammal was hunted into extinction for its meat, fat, and hide.

Description

Steller's sea cows grew to be 8 to 9 m (26 to 30 ft) long as adults, much larger than extant sirenians.[6] Georg Steller's writings contain two contradictory estimates of weight: 4 and 24.3 t (4.4 and 26.8 short tons). The true value is estimated to fall between these figures, at about 8–10 t (8.8–11.0 short tons).[7] This size made the sea cow one of the largest mammals of the Holocene epoch, along with whales,[8] and was likely an adaptation to reduce its surface area-to-volume ratio and conserve heat.[9]

Unlike other sirenians, Steller's sea cow was positively buoyant, meaning that it was unable to submerge completely. It had a very thick outer skin, 2.5 cm (1 in), to prevent injury from sharp rocks and ice and possibly to prevent unsubmerged skin from drying out.[6][10] The sea cow's blubber was 8–10 cm (3–4 in) thick, another adaptation to the frigid climate of the Bering Sea.[11] Its skin was brownish-black, with white patches on some individuals. It was smooth along its back and rough on its sides, with crater-like depressions most likely caused by parasites. This rough texture led to the animal being nicknamed the "bark animal". Hair on its body was sparse, but the insides of the sea cow's flippers were covered in bristles.[5] The fore limbs were roughly 67 cm (26 in) long, and the tail fluke was forked.[5]

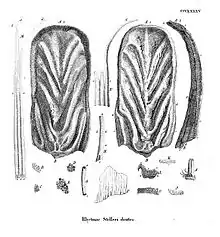

The sea cow's head was small and short in comparison to its huge body. The animal's upper lip was large and broad, extending so far beyond the lower jaw that the mouth appeared to be located underneath the skull. Unlike other sirenians, Steller's sea cow was toothless and instead had a dense array of interlacing white bristles on its upper lip. The bristles were about 3.8 cm (1.5 in) in length and were used to tear seaweed stalks and hold food.[5] The sea cow also had two keratinous plates located on its palate and mandible, used for chewing.[12] According to Steller, these plates (or "masticatory pads") were held together by interdental papillae, a part of the gums, and had many small holes containing nerves and arteries.[5]

As with all sirenians, the sea cow's snout pointed downwards, which allowed it to better grasp kelp. The sea cow's nostrils were roughly 5 cm (2 in) long and wide. In addition to those within its mouth, the sea cow also had stiff bristles 10–12.7 cm (3.9–5.0 in) long protruding from its muzzle.[9][5] Steller's sea cow had small eyes located halfway between its nostrils and ears with black irises, livid eyeballs, and canthi which were not externally visible. The animal had no eyelashes, but like other diving creatures such as sea otters, Steller's sea cow had a nictitating membrane, which covered its eyes to prevent injury while feeding. The tongue was small and remained in the back of the mouth, unable to reach the masticatory (chewing) pads.[9][5]

The sea cow's spine is believed to have had seven cervical (neck), 17 thoracic, three lumbar, and 34 caudal (tail) vertebrae. Its ribs were large, with five of 17 pairs making contact with the sternum; it had no clavicles.[5] As in all sirenians, the scapula of Steller's sea cow was fan-shaped, being larger on the posterior side and narrower towards the neck. The anterior border of the scapula was nearly straight, whereas those of modern sirenians are curved. Like other sirenians, the bones of Steller's sea cow were pachyosteosclerotic, meaning they were both bulky (pachyostotic) and dense (osteosclerotic).[9][13] In all collected skeletons of the sea cow, the manus is missing; since Dusisiren—the sister taxon of Hydrodamalis—had reduced phalanges (finger bones), Steller's sea cow possibly did not have a manus at all.[14]

The sea cow's heart was 16 kg (35 lb) in weight; its stomach measured 1.8 m (6 ft) long and 1.5 m (5 ft) wide. The full length of its intestinal tract was about 151 m (500 ft), equaling more than 20 times the animal's length. The sea cow had no gallbladder, but did have a wide common bile duct. Its anus was 10 cm (0.33 ft) in width, with its feces resembling those of horses. The male's penis was 80 cm (2.6 ft) long.[5]

Ecology and behavior

Whether Steller's sea cow had any natural predators is unknown. It may have been hunted by killer whales and sharks, though its buoyancy may have made it difficult for killer whales to drown, and the rocky kelp forests in which the sea cow lived may have deterred sharks. According to Steller, the adults guarded the young from predators.[6]

Steller described an ectoparasite on the sea cows that was similar to the whale louse (Cyamus ovalis), but the parasite remains unidentified due to the host's extinction and loss of all original specimens collected by Steller.[15] It was first formally described as Sirenocyamus rhytinae in 1846 by Johann Friedrich von Brandt. It was the only species of cyamid amphipod to be reported inhabiting a sirenian.[16] Steller also identified an endoparasite in the sea cows, which was likely an ascarid nematode.[12]

Like other sirenians, Steller's sea cow was an obligate herbivore and spent most of the day feeding, only lifting its head every 4–5 minutes for breathing.[5] Kelp was its main food source, making it an algivore. The sea cow likely fed on several species of kelp, which have been identified as Agarum spp., Alaria praelonga, Halosaccion glandiforme, Laminaria saccharina, Nereocyctis luetkeana, and Thalassiophyllum clathrus. Steller's sea cow only fed directly on the soft parts of the kelp, which caused the tougher stem and holdfast to wash up on the shore in heaps. The sea cow may have also fed on seagrass, but the plant was not common enough to support a viable population and could not have been the sea cow's primary food source. Further, the available seagrasses in the sea cow's range (Phyllospadix spp. and Zostera marina) may have grown too deep underwater or been too tough for the animal to consume. Since the sea cow floated, it likely fed on canopy kelp, as it is believed to have only had access to food no deeper than 1 m (3.3 ft) below the tide. Kelp releases a chemical deterrent to protect it from grazing, but canopy kelp releases a lower concentration of the chemical, allowing the sea cow to graze safely.[12][6][17] Steller noted that the sea cow grew thin during the frigid winters, indicating a period of fasting due to low kelp growth.[17] Fossils of Pleistocene Aleutian Island sea cow populations were larger than those from the Commander Islands, indicating that the growth of Commander Island sea cows may have been stunted due to a less favorable habitat and less food than the warmer Aleutian Islands.[9]

Steller described the sea cow as being highly social (gregarious). It lived in small family groups and helped injured members, and was also apparently monogamous. Steller's sea cow may have exhibited parental care, and the young were kept at the front of the herd for protection against predators. Steller reported that as a female was being captured, a group of other sea cows attacked the hunting boat by ramming and rocking it, and after the hunt, her mate followed the boat to shore, even after the captured animal had died. Mating season occurred in early spring and gestation took a little over a year, with calves likely delivered in autumn, as Steller observed a greater number of calves in autumn than at any other time of the year. Since female sea cows had only one set of mammary glands, they likely had one calf at a time.[5]

The sea cow used its fore limbs for swimming, feeding, walking in shallow water, defending itself, and holding on to its partner during copulation.[5] According to Steller, the fore limbs were also used to anchor the sea cow down to prevent it from being swept away by the strong nearshore waves.[6] While grazing, the sea cow progressed slowly by moving its tail (fluke) from side to side; more rapid movement was achieved by strong vertical beating of the tail. They often slept on their backs after feeding. According to Steller, the sea cow was nearly mute and made only heavy breathing sounds, raspy snorting similar to a horse, and sighs.[5]

Taxonomy

Phylogeny

| Relations within Sirenia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Based on a 2015 study by Mark Springer[18] |

| Relations within Hydrodamalinae | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Based on a 2004 study by Hitoshi Furusawa[19] |

Steller's sea cow was a member of the genus Hydrodamalis, a group of large sirenians, whose sister taxon was Dusisiren. Like those of Steller's sea cow, the ancestors of Dusisiren lived in tropical mangroves before adapting to the cold climates of the North Pacific.[20] Hydrodamalis and Dusisiren are classified together in the subfamily Hydrodamalinae,[21] which diverged from other sirenians around 4 to 8 mya.[22] Steller's sea cow is a member of the family Dugongidae, the sole surviving member of which, and thus Steller's sea cow's closest living relative, is the dugong (Dugong dugon).[23]

Steller's sea cow was a direct descendant of the Cuesta sea cow (H. cuestae),[6] an extinct tropical sea cow that lived off the coast of western North America, particularly California. The Cuesta sea cow is thought to have become extinct due to the onset of the Quaternary glaciation and the subsequent cooling of the oceans. Many populations died out, but the lineage of Steller's sea cow was able to adapt to the colder temperatures.[24] The Takikawa sea cow (H. spissa) of Japan is thought of by some researchers to be a taxonomic synonym of the Cuesta sea cow, but based on a comparison of endocasts, the Takikawa and Steller's sea cows are more derived than the Cuesta sea cow. This has led some to believe that the Takikawa sea cow is its own species.[19] The evolution of the genus Hydrodamalis was characterized by increased size, and a loss of teeth and phalanges, as a response to the onset of the Quaternary glaciation.[24][5]

Research history

Steller's sea cow was discovered in 1741 by Georg Wilhelm Steller, and was named after him. Steller researched the wildlife of Bering Island while he was shipwrecked there for about a year;[25] the animals on the island included relict populations of sea cows, sea otters, Steller sea lions, and northern fur seals.[26] As the crew hunted the animals to survive, Steller described them in detail. Steller's account was included in his posthumous publication De bestiis marinis, or The Beasts of the Sea, which was published in 1751 by the Russian Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg. Zoologist Eberhard von Zimmermann formally described Steller's sea cow in 1780 as Manati gigas. Biologist Anders Jahan Retzius in 1794 put the sea cow in the new genus Hydrodamalis, with the specific name of stelleri, in honor of Steller.[4] In 1811, naturalist Johann Karl Wilhelm Illiger reclassified Steller's sea cow into the genus Rytina, which many writers at the time adopted. The name Hydrodamalis gigas, the correct combinatio nova if a separate genus is recognised, was first used in 1895 by Theodore Sherman Palmer.[5]

For decades after its discovery, no skeletal remains of a Steller's sea cow were discovered.[10] This may have been due to rising and falling sea levels over the course of the Quaternary period, which could have left many sea cow bones hidden.[9] The first bones of a Steller's sea cow were unearthed in about 1840, over 70 years after it was presumed extinct. The first partial sea cow skull was discovered in 1844 by Ilya Voznesensky while on the Commander Islands, and the first skeleton was discovered in 1855 on northern Bering Island. These specimens were sent to Saint Petersburg in 1857, and another nearly complete skeleton arrived in Moscow around 1860. Until recently, all the full skeletons were found during the 19th century, being the most productive period in terms of unearthed skeletal remains, from 1878 to 1883. During this time, 12 of the 22 skeletons having known dates of collection were discovered. Some authors did not believe possible the recovery of further significant skeletal material from the Commander Islands after this period, but a skeleton was found in 1983, and two zoologists collected about 90 bones in 1991.[10] Only two to four skeletons of the sea cow exhibited in different museums of the world originate from a single individual.[27] It is known that Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld, Benedykt Dybowski, and Leonhard Hess Stejneger unearthed many skeletal remains from different individuals in the late 1800s, from which composite skeletons were assembled. As of 2006, 27 nearly complete skeletons and 62 complete skulls have been found, but most of them are assemblages of bones from two to 16 different individuals.[10]

Sea cow bones are found regularly on the Commander Islands, but to find a full skeleton of the Steller's sea cow is an extremely rare event. However, in November 2017, during regular monitoring of the coastal line Marina Shitova, researchers of the Commander Islands Nature and Biosphere Reserve found a new skeleton of this animal. The skeleton was at a depth of 70 centimeters (28 in) and consisted of 45 spinal bones, 27 ribs, a left shoulder blade, shoulder and forearm bones and several wrist bones. There was no skull, cervical spine, first and second dorsal vertebrae, several caudal vertebrae, the right part of the pectoral arch, or metacarpus and phalangeal bones of the left limb. The total length of the skeleton was 5.2 meters (17 ft). Taking into account the length of the absent part of the spine and the head it was assumed that the animal was about 6 meters (20 ft) long.[28] The last full skeleton of this animal (about 3 meters i.e. 9.8 ft long), was also found on Bering Island in 1987 and is now in the Aleutian Museum of Natural History at Nikolskoye.[29][30]

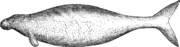

Illustrations

The Pallas Picture is the only known drawing of Steller's sea cow believed to be from an actual specimen. It was published by Peter Simon Pallas in his 1840 work Icones ad Zoographia Rosso-Asiatica. Pallas did not specify a source; Stejneger suggested it may have been one of the original illustrations produced by Friedrich Plenisner, a member of Vitus Bering's crew as a painter and surveyor who drew a figure of a female sea cow on Steller's request. Most of Plenisner's depictions were lost during transit from Siberia to Saint Petersburg.[31][32]

Another drawing of Steller's sea cow similar to the Pallas Picture appeared on a 1744 map drawn by Sven Waxell and Sofron Chitrow. The picture may have also been based upon a specimen, and was published in 1893 by Pekarski. The map depicted Vitus Bering's route during the Great Northern Expedition, and featured illustrations of Steller's sea cow and Steller's sea lion in the upper-left corner. The drawing contains some inaccurate features such as the inclusion of eyelids and fingers, leading to doubt that it was drawn from a specimen.[31][32]

Johann Friedrich von Brandt, director of the Russian Academy of Sciences, had the "Ideal Image" drawn in 1846 based upon the Pallas Picture, and then the "Ideal Picture" in 1868 based upon collected skeletons. Two other possible drawings of Steller's sea cow were found in 1891 in Waxell's manuscript diary. There was a map depicting a sea cow, as well as a Steller sea lion and a northern fur seal. The sea cow was depicted with large eyes, a large head, claw-like hands, exaggerated folds on the body, and a tail fluke in perspective lying horizontally rather than vertically. The drawing may have been a distorted depiction of a juvenile, as the figure bears a resemblance to a manatee calf. Another similar image was found by Alexander von Middendorff in 1867 in the library of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and is probably a copy of the Tsarskoye Selo Picture.[31][32]

The Pallas Picture: the only surviving drawing of Steller's sea cow by Friedrich Plenisner, and possibly the only one drawn from a specimen (1840)

The Pallas Picture: the only surviving drawing of Steller's sea cow by Friedrich Plenisner, and possibly the only one drawn from a specimen (1840).jpg.webp) The Pekarski Picture: a map of the Commander Islands including illustrations of Steller's sea cow and the Steller sea lion by a crew member of Vitus Bering's Great Northern Expedition (1893)

The Pekarski Picture: a map of the Commander Islands including illustrations of Steller's sea cow and the Steller sea lion by a crew member of Vitus Bering's Great Northern Expedition (1893) The Ideal Image by Johann Friedrich von Brandt based on the Pallas Picture (1846)

The Ideal Image by Johann Friedrich von Brandt based on the Pallas Picture (1846) The Ideal Picture by Johann Friedrich von Brandt based on the Pallas Picture and skeletons (1868)

The Ideal Picture by Johann Friedrich von Brandt based on the Pallas Picture and skeletons (1868) The Tsarskoye Selo Picture: a map of the Commander Islands, including illustrations of Steller's sea cow, the Steller sea lion, and the northern fur seal, by Sven Waxell (1891); the tail is lying flat on the ground in perspective.

The Tsarskoye Selo Picture: a map of the Commander Islands, including illustrations of Steller's sea cow, the Steller sea lion, and the northern fur seal, by Sven Waxell (1891); the tail is lying flat on the ground in perspective. The second Tsarskoye Selo Picture by Sven Waxell (1891)

The second Tsarskoye Selo Picture by Sven Waxell (1891)

Range

| Locations of confirmed sightings and subfossil remains of Steller's sea cow[33][34] |

The range of Steller's sea cow at the time of its discovery was apparently restricted to the shallow seas around the Commander Islands, which include Bering and Copper Islands.[34][10][5] The Commander Islands remained uninhabited until 1825, when the Russian-American Company relocated Aleuts from Attu Island and Atka Island there.[35] The first fossils discovered outside the Commander Islands were found in interglacial Pleistocene deposits in Amchitka,[9] and further fossils dating to the late Pleistocene were found in Monterey Bay, California, and Honshu, Japan. This suggests that the sea cow had a far more extensive range in prehistoric times. It cannot be excluded that these fossils belong to other Hydrodamalis species.[10][36][37] The southernmost find is a Middle Pleistocene rib bone from the Bōsō Peninsula of Japan.[38] The remains of three individuals were found preserved in the South Bight Formation of Amchitka; as late Pleistocene interglacial deposits are rare in the Aleutians, the discovery suggests that sea cows were abundant in that era. According to Steller, the sea cow often resided in the shallow, sandy shorelines and in the mouths of freshwater rivers.[9]

Bone fragments and accounts by native Aleut people suggest that sea cows also historically inhabited the Near Islands,[39] potentially with viable populations that were in contact with humans in the western Aleutian Islands prior to Steller's discovery in 1741. A sea cow rib discovered in 1998 on Kiska Island was dated to around 1,000 years old, and is now in the possession of the Burke Museum in Seattle. The dating may be skewed due to the marine reservoir effect which causes radiocarbon-dated marine specimens to appear several hundred years older than they are. Marine reservoir effect is caused by the large reserves of C14 in the ocean, and it is more likely that the animal died between 1710 and 1785.[33]

A 2004 study reported that sea cow bones discovered on Adak Island were around 1,700 years old, and sea cow bones discovered on Buldir Island were found to be around 1,600 years old.[40] It is possible the bones were from cetaceans and were misclassified.[33] Rib bones of a Steller's sea cow have also been found on St. Lawrence Island, and the specimen is thought to have lived between 800 and 920 CE.[34]

Interactions with humans

Interactions with Europeans

Steller's sea cow was quickly wiped out by fur traders, seal hunters, and others who followed Vitus Bering's route past its habitat to Alaska.[41] It was also hunted to collect its valuable subcutaneous fat. The animal was hunted and used by Ivan Krassilnikov in 1754 and Ivan Korovin 1762, but Dimitri Bragin, in 1772, and others later, did not see it. Brandt thus concluded that by 1768, twenty-seven years after it had been discovered by Europeans, the species was extinct.[1][36][42] In 1887, Stejneger estimated that there had been fewer than 1,500 individuals remaining at the time of Steller's discovery, and argued there was already an immediate danger of the sea cow's extinction.[1]

The first attempt to hunt the animal by Steller and the other crew members was unsuccessful due to its strength and thick hide. They had attempted to impale it and haul it to shore using a large hook and heavy cable, but the crew could not pierce its skin. In a second attempt a month later, a harpooner speared an animal, and men on shore hauled it in while others repeatedly stabbed it with bayonets. It was dragged into shallow waters, and the crew waited until the tide receded and it was beached to butcher it.[26] After this, they were hunted with relative ease, the challenge being in hauling the animal back to shore. This bounty inspired maritime fur traders to detour to the Commander Islands and restock their food supplies during North Pacific expeditions.[9]

Interaction with aboriginals

The presence of Steller's sea cows in the Aleutian Islands may have caused the Aleut people to migrate westward to hunt them. This possibly led to the sea cow's extinction in that area, assuming the animals survived in that region into the Holocene epoch, but there is no archaeological evidence.[9]

It has also been argued that the decline of Steller's sea cow may have been an indirect effect of the harvesting of sea otters by the area's aboriginal people. With the otter population reduced, sea urchin population would have increased, in turn reducing the stock of kelp, its principal food.[17][36] In historic times, though, aboriginal hunting had depleted sea otter populations only in localized areas,[36] and as the sea cow would have been easy prey for aboriginal hunters, accessible populations may have been exterminated with or without simultaneous otter hunting. In any event, the range of the sea cow was limited to coastal areas off uninhabited islands by the time Bering arrived, and the animal was already endangered.[43][8]

One factor potentially leading to extinction of Steller's sea cow, specifically off the coast of St. Lawrence Island, was the Siberian Yupik people who have inhabited St. Lawrence island for 2,000 years. They may have hunted the sea cows into extinction, as the natives have a dietary culture heavily dependent upon marine mammals. The onset of the Medieval Warm Period which reduced the availability of kelp may have also been the cause for their local extinction in that area.[34]

Later reported sightings

Sea cow sightings have been reported after Brandt's official 1768 date of extinction. Lucien Turner, an American ethnologist and naturalist, said the natives of Attu Island reported that the sea cows survived into the 1800s, and were sometimes hunted.[33]

In 1963, the official journal of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR published an article announcing a possible sighting. The previous year, the whaling ship Buran had reported a group of large marine mammals grazing on seaweed in shallow water off Kamchatka,[44] in the Gulf of Anadyr. The crew reported seeing six of these animals ranging from 6 to 8 meters (20 to 26 ft), with trunks and split lips. There have also been alleged sightings by local fishermen in the northern Kuril Islands, and around the Kamchatka and Chukchi peninsulas.[45][46]

Uses

Steller's sea cow was described as being "tasty" by Steller; the meat was said to have a taste similar to corned beef, though it was tougher, redder, and needed to be cooked longer. The meat was abundant on the animal, and slow to spoil, perhaps due to the high amount of salt in the animal's diet effectively curing it. The fat could be used for cooking and as an odorless lamp oil. The crew of the St. Peter drank the fat in cups and Steller described it as having a taste like almond oil.[47] The thick, sweet milk of female sea cows could be drunk or made into butter,[5] and the thick, leathery hide could be used to make clothing, such as shoes and belts, and large skin boats sometimes called baidarkas or umiaks.[12]

Towards the end of the 19th century, bones and fossils from the extinct animal were valuable and often sold to museums at high prices. Most were collected during this time, limiting trade after 1900.[10] Some are still sold commercially, as the highly dense cortical bone is well-suited for making items such as knife handles and decorative carvings.[10] Because the sea cow is extinct, native artisan products made in Alaska from this "mermaid ivory" are legal to sell in the United States and do not fall under the jurisdiction of the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) or the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which restrict the trade of marine mammal products. Although the distribution is legal, the sale of unfossilized bones is generally prohibited and trade in products made of the bones is regulated because some of the material is unlikely to be authentic and probably comes from arctic cetaceans.[10][48]

The ethnographer Elizabeth Porfirevna Orlova, from the Russian Museum of Ethnography, was working on the Commander Island Aleuts from August to September 1961. Her research includes notes about a game of accuracy, called "kakan"–meaning "stones"–played with the bones of the Steller's sea cow. Kakan was usually played at home between adults during bad weather, at least during Orlova's fieldwork.[49]

In media and folklore

In the story The White Seal from The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling, which takes place in the Bering Sea, Kotick the rare white seal consults Sea Cow during his journey to find a new home.[50][51]

Tales of a Sea Cow is a 2012 docufiction film by Icelandic-French artist Etienne de France about a fictional 2006 discovery of Steller's sea cows off the coast of Greenland.[52] The film has been exhibited in art museums and universities in Europe.[53][54]

Steller's sea cows appear in two books of poetry: Nach der Natur (1995) by Winfried Georg Sebald, and Species Evanescens (2009) by Russian poet Andrei Bronnikov. Bronnikov's book depicts the events of the Great Northern Expedition through the eyes of Steller;[55] Sebald's book looks at the conflict between man and nature, including the extinction of Steller's sea cow.[56]

See also

- Holocene extinction

- List of extinct animals of North America

- List of Asian animals extinct in the Holocene

- List of recently extinct mammals

- Evolution of sirenians

- Cuesta sea cow

- Takikawa sea cow

References

- Domning, D. (2016). "Hydrodamalis gigas". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T10303A43792683. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T10303A43792683.en.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Shoshani, J. (2005). "Hydrodamalis". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M., eds. (2005). "Hydrodamalis gigas". Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Palmer, Theodore S. (1895). "The Earliest Name for Steller's sea cow and Dugong". Science. 2 (40): 449–450. doi:10.1126/science.2.40.449-a. PMID 17759916.

- Forsten, Ann; Youngman, Phillip M. (1982). "Hydrodamalis gigas" (PDF). Mammalian Species (165): 1–3. doi:10.2307/3503855. JSTOR 3503855. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-20.

- Marsh, Helene; O'Shea, Thomas J.; Reynolds III, John E. (2011). "Steller's sea cow: discovery, biology and exploitation of a relict giant sirenian". Ecology and Conservation of the Sirenia: Dugongs and Manatees. New York, New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 18–35. ISBN 978-0-521-88828-8. OCLC 778803577.

- Scheffer, Victor B. (November 1972). "The Weight of the Steller Sea Cow". Journal of Mammalogy. 53 (4): 912–914. doi:10.2307/1379236. JSTOR 1379236.

- Turvey, S. T.; Risley, C. L. (2006). "Modelling the extinction of Steller's sea cow". Biology Letters. 2 (1): 94–97. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0415. PMC 1617197. PMID 17148336.

- Whitmore Jr., Frank C.; Gard Jr., L. M. (1977). "Steller's Sea Cow (Hydrodamalis gigas) of Late Pleistocene Age from Amchitka, Aleutian Islands, Alaska" (PDF). Geological Survey Professional Paper. Professional Paper. 1036. doi:10.3133/pp1036.

- Mattioli, Stefano; Domning, Daryl P. (2006). "An Annotated List of Extant Skeletal Material of Steller's Sea Cow (Hydrodamalis gigas) (Sirenia: Dugongidae) from the Commander Islands". Aquatic Mammals. 32 (3): 273–288. doi:10.1578/AM.32.3.2006.273.

- Berta, Annalisa (2012). Return to the Sea: The Life and Evolutionary Times of Marine Mammals. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-520-27057-2. OCLC 757476446.

Steller described the sea cow's blubber, 8–10 centimeters (3.1–3.9 in) thick, as...

- Anderson, P. K.; Domning, D. P. (2008). Perrin, William F.; Wursig, Bernd; Thewissen, J. G. M. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals (2nd ed.). San Diego, California: Academic Press. pp. 1104–1106. ISBN 978-0-12-373553-9. OCLC 262718627.

- Berta, A.; Sumich, J. L.; Kovacs, K. M. (2015). "Sirenians". Marine Mammals: Evolutionary Biology (3rd ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Academic Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-12-397002-2. OCLC 953575838.

The skeleton of sirenians displays both pachyostosis and osteosclerosis...

- Takahashi, S.; Domning, D. P.; Saito, T. (1986). "Dusisiren dewana, n. sp. (Mammalia: Sirenia), a new ancestor of Steller's sea cow from the upper Miocene of Yamagata Prefecture, northeastern Japan" (PDF). Transactions and Proceedings of the Paleontological Society of Japan, New Series (141): 296–321.

...the phalanges were even more reduced, and possibly even completely lost, in Steller's sea cow.

- Loker, Eric; Hofkin, Bruce (2015). Parasitology: A Conceptual Approach. New York, New York: Taylor and Francis Group. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-8153-4473-5. OCLC 929783662.

- Carlton, J. T.; Geller, J. B.; Reaka-Kudla, M. L.; Norse, E. A. (1999). "Historical Extinctions in the Sea" (PDF). Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 30: 523. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.30.1.515. JSTOR 221694.

Syrenocyamus rhytinae was recorded from the Steller's Sea Cow...cyamid amphipods are known only from whales and dolphins, and have never (since Steller) been recorded in sirenians.

- Estes, James A.; Burdin, Alexander; Doak, Daniel F. (2016). "Sea otters, kelp forests, and the extinction of Steller's sea cow". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (4): 880–885. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113..880E. doi:10.1073/pnas.1502552112. PMC 4743786. PMID 26504217.

- Springer, M.; Signore, A. V.; Paijmans, J. L. A.; Vélez-Juarbe, J.; Domning, D. P.; Bauer, C. E.; He, K.; Crerar, L.; Campos, P. F.; Murphy, W. J.; Meredith, R. W.; Gatesy, J.; Willerslev, E.; MacPhee, R. D.; Hofreiter, M.; Campbell, K. L. (2015). "Interordinal gene capture, the phylogenetic position of Steller's sea cow based on molecular and morphological data, and the macroevolutionary history of Sirenia". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 91 (10): 178–193. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2015.05.022. PMID 26050523.

- Furusawa, Hitoshi (2004). "A phylogeny of the North Pacific Sirenia (Dugongidae: Hydrodamalinae) based on a comparative study of endocranial casts". Paleontological Research. 8 (2): 91–98. doi:10.2517/prpsj.8.91. S2CID 83992432.

- Domning, D. P. (1978). Sirenian evolution in the North Pacific Ocean. 118. Berkeley, California: University of California Publications in Geological Sciences. pp. 1–176. ISBN 978-0-520-09581-6. OCLC 895212825.

- Hydrodamalinae at fossilworks.org (retrieved 12 March 2017)

- Rainey, W. E.; Lowenstein, J. M.; Sarich, V. M.; Magor, D. M. (1984). "Sirenian molecular systematics—including the extinct Steller's sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas)". Naturwissenschaften. 71 (11): 586–588. Bibcode:1984NW.....71..586R. doi:10.1007/BF01189187. PMID 6521758. S2CID 28213762.

- Marsh, Helene (1989). "Chapter 57: Dugongidae" (PDF). Fauna of Australia. 1B. Canberra, Australia: CSIRO. ISBN 978-0-644-06056-1. OCLC 27492815. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-11.

- Domning, Daryl P. (1978). "An Ecological Model for Late Tertiary Sirenian Evolution in the North Pacific Ocean". Systematic Zoology. 25 (4): 352–362. doi:10.2307/2412510. JSTOR 2412510.

- Steller, G. W. (1988). Frost, O. W. (ed.). Journal of a Voyage with Bering, 1741–1742. Translated by Engel, M. A.; Frost, O. W. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2181-3. OCLC 877954975.

- Frost, Orcutt William (2003). "Shipwreck and Survival". Bering: The Russian Discovery of America. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. pp. 262–264. ISBN 978-0-300-10059-4. OCLC 851981991.

- "Look, no hands: Steller's sea cow". The Guardian – Science Animal magic. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- "Skeleton of Ancient Sea Cow Found on Bering Island". The Commander Islands Nature and Biosphere Reserve Named Marakov S.V. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- "Found: The Massive Skeleton of a Steller's Sea Cow". Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- "Steller's sea cow – Sunken flagship of the Bering Sea... – The AMIQ Institute". Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- Stejneger, L. H. (1936). Georg Wilhelm Steller, the Pioneer of Alaskan Natural History. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 1–623. ISBN 978-0-576-29124-8. OCLC 836920902.

- Buechner, E. (1891). "Nordischen Seekuh". Memoirs of the Imperial Academy of St. Petersburg Science (in German). 38 (7): 1–24.

- Domning, Daryl P.; Thomason, James; Corbett, Debra G. (2007). "Steller's sea cow in the Aleutian Islands". Marine Mammal Science. 23 (4): 976–983. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2007.00153.x.

- Crerar, Lorelei D.; Crerar, Andrew P.; Domning, Daryl P.; Parsons, E. C. M. (2014). "Rewriting the history of an extinction—was a population of Steller's sea cows (Hydrodamalis gigas) at St Lawrence Island also driven to extinction?". Biology Letters. 10 (11): 20140878. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2014.0878. PMC 4261872. PMID 25428930.

- Derbeneva, Olga A.; Sukernik, Rem I.; Volodko, Natalia V.; Hosseini, Seyed H.; Lott, Marie T.; Wallace, Douglas C. (2002). "Analysis of Mitochondrial DNA Diversity in the Aleuts of the Commander Islands and Its Implications for the Genetic History of Beringia". American Journal of Human Genetics. 71 (2): 415–421. doi:10.1086/341720. PMC 379174. PMID 12082644.

In 1825–1826, the Russian-American company transferred Aleut families from Attu Island, the westernmost of the Aleutian chain, as well as from Atka/Andreyanov Islands, to the Commanders

- Anderson, Paul K. (July 1995). "Competition, Predation, and the Evolution and Extinction of Steller's Sea Cow, Hydrodamalis gigas". Marine Mammal Science. 11 (3): 391–394. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1995.tb00294.x.

- MacDonald, Stephen O.; Cook, Joseph A. (2009). Recent Mammals of Alaska. Fairbanks, Alaska: University of Alaska Press. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-1-60223-047-7. OCLC 488523994.

- Furusawa, H.; Kohno, N. (1994). "Steller's sea-cow (Sirenia: Hydrodamalis gigas) from the Middle Pleistocene Mandano Formation of the Boso Peninsula, central Japan". Japanese Paleontological Society (in Japanese). 56. doi:10.14825/kaseki.56.0_26.

- Corbett, D. G.; Causey, D.; Clemente, M.; Koch, P. L.; Doroff, A.; Lefavre, C.; West, D. (2008). "Aleut Hunters, Sea Otters, and Sea Cows". Human Impacts on Ancient Marine Ecosystems. University of California Press. pp. 43–76. ISBN 978-0-520-93429-0. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt1pphh3. OCLC 929645577.

- Savinetsky, A. B.; Kiseleva, N. K.; Khassanov, B. F. (2004). "Dynamics of sea mammaland bird populations of the Bering Sea region over the last several millennia". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 209 (1–4): 335–352. Bibcode:2004PPP...209..335S. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2004.02.009.

- Haycox, Stephen W. (2002). Alaska: An American Colony. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press. pp. 55, 144. ISBN 978-0-295-98249-6. OCLC 49225731.

Each year, one or more vessels left Okhotsk or Petropavlosk on Kamchatka for hunting trips to the [Aleutian] islands. Typically, the ships would sail to the Commander Islands, where they would spend some time slaughtering and preserving the mat of Steller's rhytina (a sea cow)...

- Jones, Ryan T. (September 2011). "A 'Havock Made among Them': Animals, Empire, and Extinction in the Russian North Pacific, 1741–1810". Environmental History. 16 (4): 585–609. doi:10.1093/envhis/emr091. JSTOR 23049853.

- Ellis, Richard (2004). No Turning Back: The Life and Death of Animal Species. New York, New York: Harper Perennial. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-06-055804-8. OCLC 961898476.

- Silverberg, R. (1973). The Dodo, the Auk and the Oryx. London, United Kingdom: Puffin Books. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-14-030619-4. OCLC 473809649.

- Berzin, A. A.; Tikhomirov, E. A.; Troinin, V. I. (2007) [1963]. Translated by Ricker, W. E. "Ischezla li Stellerova korova?" [Was Steller's sea cow exterminated?] (PDF). Priroda. 52 (8): 73–75.

- Bertram, C.; Bertram, K. (1964). "Does the 'extinct' sea cow survive?". New Scientist. 24 (415): 313.

- Littlepage, Dean. Steller's Island: Adventures of a Pioneer Naturalist in Alaska.

- Crerar, L. D.; Freeman, E. W.; Domning, D. P.; Parsons, E. C. M. (2017). "Illegal Trade of Marine Mammal Bone Exposed: Simple Test Identifies Bones of 'Mermaid Ivory' or Steller's Sea Cow (Hydrodamalis gigas)". Frontiers in Marine Science. 3 (272). doi:10.3389/fmars.2016.00272. S2CID 35462508.

- Korsun, S. A. (2013). "Fieldwork on the Commander Islands Aleuts" (PDF). Alaska Journal of Anthropology. 11 (1–2): 169–181.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Kipling, Rudyard (1894). "The White Seal". The Jungle Books. ISBN 978-0-585-00499-0. OCLC 883570362.

- Kipling, Rudyard (2013) [1894]. Nagai, Kaori (ed.). The Jungle Books. Penguin UK. p. 405. ISBN 978-0-14-196839-1. OCLC 851153394.

- "Tales of a Sea Cow (2012)". IMDb. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- "Etienne de France, 'Tales of a Sea Cow' — Exhibition at Parco Arte Vivente, Torino, Italy". alan-shapiro.com. Archived from the original on 2014-05-02. Retrieved 2014-05-01.

- Bureaud, Annick. "Tales of a Sea Cow: A Fabulatory Science Story" (PDF). Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- Bronnikov, Andrei (2009). Species Evanescens (in Russian). Reflections. ISBN 978-90-79625-02-4. OCLC 676724013.

- Sebald, W. G. "Nach der Natur Sebald" (in German). Hanser Literaturverlage. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

Further reading

- Steller, Georg W. (2011) [1751]. "The Manatee". In Miller, Walter (ed.). De Bestiis Marinis. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska. pp. 13–43. ISBN 978-1-295-08525-5. OCLC 867637409.

- Steller, G. W. (1925). "Appendix A: Topographical and Physical Description of Bering Island which Lies in the Eastern Sea off the Coast of Kamchatka" (PDF). In Golder, F. A. (ed.). Steller's Journal of the Sea Voyage from Kamchatka to America and Return on the Second Expedition, 1741–1742. Bering's Voyages: An Account of the Efforts of the Russians to Determine the Relation of Asia and America. II. Translated by Stejneger, Leonhard. New York, New York: American Geographical Society. p. 207.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hydrodamalis gigas. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Hydrodamalis gigas. |