Sustainable consumption

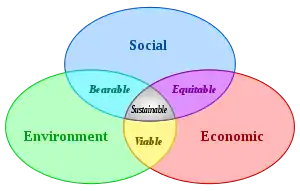

Sustainable consumption (sometimes abbreviated to "SC")[1] is the use of material products, energy and immaterial services in such a way that their use minimizes impacts on the environment, so that human needs can be met not only in the present but also for future generations.[2] Consumption refers not only to individuals and households, but also to governments, business, and other institutions. Sustainable consumption is closely related to sustainable production and sustainable lifestyles. "A sustainable lifestyle minimizes ecological impacts while enabling a flourishing life for individuals, households, communities, and beyond. It is the product of individual and collective decisions about aspirations and about satisfying needs and adopting practices, which are in turn conditioned, facilitated, and constrained by societal norms, political institutions, public policies, infrastructures, markets, and culture."[3]

| Part of series on |

| Anti-consumerism |

|---|

The United Nations includes analyses of efficiency, infrastructure, and waste, as well as access to basic services, green and decent jobs and a better quality of life for all within the concept of sustainable consumption.[4] It shares a number of common features with and is closely linked to the terms sustainable production and sustainable development. Sustainable consumption, as part of sustainable development, is a prerequisite in the worldwide struggle against sustainability challenges such as climate change, resource depletion, famines or environmental pollution.

Sustainable development as well as sustainable consumption rely on certain premises such as:

- Effective use of resources, and minimisation of waste and pollution

- Use of renewable resources within their capacity for renewal

- Fuller product life-cycles

- Intergenerational and intragenerational equity

Goal 12 of the Sustainable Development Goals seeks to "ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns".[5]

The Oslo definition

In 1994 the Oslo symposium defined sustainable consumption as the consumption of goods and services that enhance quality of life while limiting the use of natural resources and noxious materials.[6]

Strong and weak sustainable consumption

Some writers make a distinction between "strong" and "weak" sustainability.[7]

In 1992, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), also referred as the Earth Summit, recognized sustainable consumption.[8] They also recognized the difference between strong and weak sustainable consumption but set their efforts away from strong sustainable consumption.[9] Strong sustainable consumption refers to participating in viable environmental activities, such as consuming renewable and efficient goods and services (Example: electric locomotive, cycling, renewable energy).[9] Strong sustainable consumption also refers to an urgency to reduce individual living space and consumption rate. Contrarily, weak sustainable consumption is the failure to adhere to strong sustainable consumption. In other words, consumption of highly pollutant activities, such as frequent car use and consumption of non-biodegradable goods (Example: plastic items, metals, and mixed fabrics).[9]

The 1992 Earth Summit, found that sustainable consumption rather than sustainable development, was the center of political discourse.[8] Currently, strong sustainable consumption is only present in minimal precincts of discussion and research. International government organizations’ (IGOs) prerogatives have kept away from strong sustainable consumption. To avoid scrutiny, IGOs have deemed their influences as limited, often aligning its interests with consumer wants and needs.[9] In doing so, they advocate for minimal eco-efficient improvements, resulting in government skepticism and minimal commitments to strong sustainable consumption efforts.[10]

In order to achieve sustainable consumption, two developments have to take place: it requires both an increase in the efficiency of consumption as well as a change in consumption patterns and reductions in consumption levels in industrialized countries as well as rich social classes in developing countries which have also a large ecological footprint and give examples for increasing middle classes in developing countries.[11] The first prerequisite is not sufficient on its own and can be named weak sustainable consumption. Here, technological improvements and eco-efficiency support a necessary reduction in resource consumption. Once this aim has been met, the second prerequisite, the change in patterns and reduction of levels of consumption is indispensable. Strong sustainable consumption approaches also pay attention to the social dimension of well-being and assess the need for changes based on a risk-averse perspective.[12] In order to achieve what can be termed strong sustainable consumption, changes in infrastructures as well as the choices customers have are required. In the political arena, weak sustainable consumption has been discussed whereas strong sustainable consumption is missing from all debates.[13]

The so-called attitude-behaviour or values-action gap describes a significant obstacle to changes in individual customer behavior. Many consumers are well aware of the importance of their consumption choices and care about environmental issues, however, most of them do not translate their concerns into their consumption patterns as the purchase-decision making process is highly complicated and relies on e.g. social, political and psychological factors. Young et al. identified a lack of time for research, high prices, a lack of information and the cognitive effort needed as the main barriers when it comes to green consumption choices.[14]

Ecological Awareness

The recognition that human well-being is interwoven with the natural environment, as ell as an interest to change human activities that cause environmental harm.[15]

Historical Behaviors Related to Sustainable Consumption

The early twentieth century, especially during the interwar period, founded an influx of families turning to sustainable consumption.[6] When unemployment began to stretch resources, American working-class families increasingly became dependent on secondhand goods, such as clothing, tools, and furniture.[6] Used items offered entry into consumer culture, as comforts were not always available. Not only were secondhand products an entry to consumer culture, they also provided investment value, and enhancements to wage-earning capabilities.[6] The Great Depression saw increases in the number of families forced to turn to cast off clothing as attires became unsuitable. When wages became desperate, employers offered clothing replacements as a substitute for earnings. In response, fashion trends decelerated as high end clothing became a luxury.

During the rapid expansion of post-war suburbia, families turned to new levels of mass consumption. Following the SPI conference of 1956, plastic corporations were quick to enter the mass consumption market of post-war America.[16] During this period companies like Dixie began to replace reusable products with disposable containers (plastic items and metals). Unaware of how to dispose of containers, consumers began to throw waste across public spaces and national parks.[16] Following a Vermont State Legislature ban on disposable glass products, plastic corporations banded together to form the Keep America Beautiful organization in order to encourage individual actions and discourage regulation.[16] Upon the organization's adoption, the organization teamed with schools and government agencies to spread the anti-litter message. Running public service announcements like Susan Spotless, the organization encouraged consumers to dispose waste in designated areas. Proceeding mass media campaigns, trash disposal became a social phenomenon for consumption.

Recent Culture Shifts

More recently, surveys ranking consumer values such as environmental, social, and sustainability, showed sustainable consumption values to be particularly low.[17] Additionally, surveys studying environmental awareness saw an increase in perceived “eco-friendly” behavior. When tasked to reduce energy consumption, empirical research found that individuals are only willing to make minimal sacrifices and fail to reach the strong sustainable consumption requirements.[18] From a policy perspective, IGOs are not motivated to adopt sustainable policy decisions, since consumer demands may not meet the requirements of sustainable consumption.

Ethnographic research across Europe concluded that post Financial Crisis of 2007-2008 Ireland, saw an increase in secondhand shopping and communal gardening.[19] Following a series of financial scandals, Anti-Austerity became a cultural movement. Irish consumer confidence fell, sparking a culture shift in second-hand markets and charities, thereby stressing sustainability and drawing on a narrative surrounding economic recovery.[17]

Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals were established by the United Nations in 2015. SDG 12 is described as to "ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns".[20] Specifically, targets 12.1 and 12.A of SDG 12 aim to implement frameworks and support developing countries in order to "move towards more sustainable patterns of consumption and production".[20]

Notable conferences and programs

- 1992 - At the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) the concept of sustainable consumption was established in chapter 4 of the Agenda 21.[21]

- 1995 – Sustainable consumption was requested to be incorporated by UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) into the UN Guidelines on Consumer Protection.

- 1997 – A major report on SC was produced by the OECD.[22]

- 1998 – United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) started a SC program and SC is discussed in the Human Development Report of the UN Development Program (UNDP).[23]

- 2002 – A ten-year program on sustainable consumption and production (SCP) was created in the Plan of Implementation at the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) in Johannesburg.[24]

- 2003 - The "Marrakesh Process" was developed by co-ordination of a series of meetings and other "multi-stakeholder" processes by UNEP and UNDESA following the WSSD.[25]

- 2018 - Third International Conference of the Sustainable Consumption Research and Action Initiative (SCORAI) in collaboration with the Copenhagen Business School.[26]

See also

References

- Consumer Council (Hong Kong), Sustainable Consumption for a Better Future – A Study on Consumer Behaviour and Business Reporting, published 22 February 2016, accessed 13 September 2020

- Our common future. World Commission on Environment and Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1987. ISBN 978-0192820808. OCLC 15489268.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Vergragt, P.J. et al (2016) Fostering and Communicating Sustainable Lifestyles: Principles and Emerging Practices, UNEP– Sustainable Lifestyles, Cities and Industry Branch, http://www.oneearthweb.org/communicating-sustainable-lifestyles-report.html , page 6.

- "Sustainable consumption and production". United Nations Sustainable Development. Retrieved 2018-08-15.

- "Goal 12: Responsible consumption, production". UNDP. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- Source: Norwegian Ministry of the Environment (1994) Oslo Roundtable on Sustainable Production and Consumption.

- Ross, A., Modern Interpretations of Sustainable Development, Journal of Law and Society , Mar., 2009, Vol. 36, No. 1, Economic Globalization and Ecological Localization: Socio-legal Perspectives (Mar., 2009), pp. 32-54

- "United Nations Conference on Environment & Development" (PDF). Sustainable Development.

- "Sustainable Consumption Governance: A History of - ProQuest". www.proquest.com. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- Perrels, Adriaan (2008-07-01). "Wavering between radical and realistic sustainable consumption policies: in search for the best feasible trajectories". Journal of Cleaner Production. The Governance and Practice of Change of Sustainable Consumption and Production. 16 (11): 1203–1217. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2007.08.008. ISSN 0959-6526.

- Meier, Lars; Lange, Hellmuth, eds. (2009). The New Middle Classes. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9938-0. ISBN 978-1-4020-9937-3.

- Lorek, Sylvia; Fuchs, Doris (2013). "Strong Sustainable Consumption Governance - Precondition for a Degrowth Path?". Journal of Cleaner Production. 38: 36–43. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.08.008.

- Fuchs, Doris; Lorek, Sylvia (2005). "Sustainable Consumption Governance: A History of Promises and Failures". Journal of Consumer Policy. 28 (3): 261–288. doi:10.1007/s10603-005-8490-z. S2CID 154853001.

- Young, William (2010). "Sustainable Consumption: Green Consumer Behaviour when Purchasing Products" (PDF). Sustainable Development (18): 20–31.

- Ruby, Matthew B.; Walker, Iain; Watkins, Hanne M. (2020). "Sustainable Consumption: The Psychology of Individual Choice, Identity, and Behavior". Journal of Social Issues. 76 (1): 8–18. doi:10.1111/josi.12376. ISSN 1540-4560.

- "Reframing History: The Litter Myth : Throughline". NPR.org. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- https://www.ucd.ie/quinn/media/businessschool/rankingsampaccreditations/profileimages/docs/consumermarketmonitor/CMM_Q1_2016.pdf "Consumer Market Monitor | UCD Quinn School" Check

|url=value (help) (PDF). www.ucd.ie. Retrieved 2020-12-08. - "Measurement and Determinants of Environmentally Significant Consumer Behavior". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- Murphy, Fiona (2017-10-15). "Austerity Ireland, the New Thrift Culture and Sustainable Consumption". Journal of Business Anthropology. 6 (2): 158–174. doi:10.22439/jba.v6i2.5410. ISSN 2245-4217.

- UN Goal 12: Ensure Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns

- United Nations. "Agenda 21" (PDF).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (1997) Sustainable Consumption and Production, Paris: OECD.

- United Nations Development Program (UNDP) (1998) Human Development Report, New York: UNDP.

- United Nations (UN) (2002) Plan of Implementation of the World Summit on Sustainable Development. In Report of the World Summit on Sustainable Development, UN Document A/CONF.199/20*, New York: UN.

- United Nations Department of Social and Economic Affairs (2010) Paving the Way to Sustainable Consumption and Production. In Marrakech Process Progress Report including Elements for a 10-Year Framework of Programmes on Sustainable Consumption and Production (SCP). [online] Available at: http://www.unep.fr/scp/marrakech/pdf/Marrakech%20Process%20Progress%20Report%20-%20Paving%20the%20Road%20to%20SCP.pdf [Accessed: 6/11/2011].

- "Third International Conference of the Sustainable Consumption Research and Action Initiative (SCORAI)". CBS - Copenhagen Business School. 2018-03-07. Retrieved 2020-02-21.