The Third Alarm (1922 film)

The Third Alarm is a 1922 American silent melodrama film directed by Emory Johnson. Emilie Johnson, Emory's mother, wrote both the story and screenplay. The film's "All-Star" cast features Ralph Lewis, Johnnie Walker, and Emory Johnson's wife Ella Hall. The film was released on January 7, 1923.[1][2]

| The Third Alarm | |

|---|---|

Magazine advertisement | |

| Directed by | Emory Johnson Dick Rosson Asst dir |

| Produced by | Pat Powers Emory Johnson |

| Written by | Emilie Johnson |

| Screenplay by | Emilie Johnson |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Henry Sharp |

| Color process | Black and White |

| Distributed by | Film Booking Offices of America |

Release date |

|

Running time |

|

| Country | United States |

| Language |

|

Dan McDowell was a veteran fireman and driver of a horse-drawn Fire Engine. The department motorizes the station's equipment. Dan cannot master the driving skills needed to operate the new motorized vehicles. The fire chief retires Dan with a small pension. Johnny, Dan's son, is studying to become a doctor. Dan had supported his son's ambitions but now cannot support his family and Johnnie's schooling. He takes a job digging ditches.

Circumstances befall Dan, and he lives through various misfortunes. Johnnie, no longer able to afford medical school, takes a job as a fireman. All storylines converge as a major three-alarm fire breaks out. This Melodrama has a predictable happy ending.

Plot

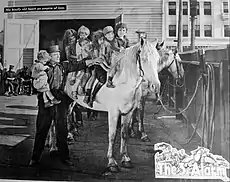

The action starts as someone trips a Fire alarm call box. Then, the fire station alarm bell clangs, a fire dispatcher utters, "We roll - Third and Western." All the firemen spring into action. We pay particular attention to engine number seven, a Steam pumper, manned by an aging fireman. The doors fling open, and the two horse-drawn fire engines barrel down the street to fight the fire. The fireman driving engine number seven is Dan McDowell, portrayed by Ralph Lewis. Dan is a twenty-year veteran of the force. Dan not only drives engine number seven but also cares for the station's five fire horses.

At the McDowell house, which stands caddy-corner from the fire station, mother McDowell, played by Virginia True Boardman, is frosting Dan's birthday cake with her daughter Alice, played by Josephine Adair. Johnny McDowell, acted by Johnnie Walker, joins the group. Johnny is studying to become a doctor and has only a year left. We meet Johnny's sweetheart, June Rutherford, played by Ella Hall.

At the fire station house, the battalion chief drives up and tells the boys they will motorize the station by the first. All the men cheer, except Dan. Dan goes home to attend his birthday party. The day of the changeover arrives. The fire crew watches the new motorized Steam pumper pull in. Later, the chief sells the five fire horses. Dan must now learn to drive the new motorized engine. He struggles to master driving skills. Unable to drive the new rig, the chief retires Dan McDowell on a small pension.

Dan's foremost concern now is Johnny's medical career. Dan tells Johnny he hasn't got enough money to support his medical studies. Johnny tells his father not to worry because his sweetheart is the daughter of a famous surgeon - Dr. Loren Rutherford.

Dan tells Johnny when he was young; his brother got sick. The boy's physician told Dan that only one man could save the boy - Dr. Loren Rutherford. Dan storms into Dr. Rutherford's office and pleads with the Dr. to save his boy. Dr. Rutherford says he can't save Dan's son because he must save another life first. Dan tells Johnny he will never forget that Dr. Rutherford let his young brother die.

To make ends meet, Dan gets a job as a ditch digger. While working one day, he notices Bullet nuzzling up against him. Bullet had been pulling a dirt wagon but visited Dan. Bullet's supervisor finds his horse and abuses the animal. Dan tries to stop him but is beat up. Johnny happens upon the altercation and beats up Bullet's handler. After threatening the supervisor, Johnny forces Dan to quit this job. Johnny decides to lifts Dan's financial burdens. He drops out of medical school and applies for a job at the fire station. The chief knows Johnny and makes him a fireman.

The next day, the police arrive at the McDowell household. They claim a fire horse is missing and blame Johnny. The police have a search warrant and find "Bullet" in Dan's shed. The police demand to know where Johnny is. Dan confesses to save his son. The police take Dan to jail. A fire breaks out in the Rutherford apartment building. June Rutherford lives on the top floor. She evacuates with the other residents when she discovers her small dog is missing. She goes back but becomes trapped by the flames.

Johnny is at the fire station when the fire bell clangs. He finds out the fire is at the new Rutherford apartments. The dispatcher says they only respond if it becomes a third alarm. Freddie is selling newspapers when he reads about Dan's arrest for a horse thief. He rushes to the fire station and tells the chief he found Bullet on the street and locked him up in Dan's woodshed. The chief says he will free Dan.

Meanwhile, at the fire, they call in a third alarm. June finds a balcony and starts screaming for help. The nearest fire truck raises a ladder to rescue her, but the ladder is too short. A fireman scrambles up the ladder–it is Johnny trying to save June. The apartment walls are collapsing, and the battalion chief orders his men to safety. The wall supporting the end of the ladder collapses, but Johnny hooks a Scaling ladder to the balcony railing and rescues June. Now they must descend to ground level. While June and the dog hang on to his back, he descends to the balcony below.

Dan has secured his release from Prison and rushes to the scene of the fire. He helps his fellow firemen handle the hoses. A large safe smashes through the apartment floors. Johnny and June survived the fall, but the safe has blocked their escape.

Meanwhile, Dr. Rutherford finds Dan and begs him to save his daughter. Dan has flashbacks about his adolescent son. He brushes the Doctor aside. Bullet, working the night shift, hears the fire alarm, breaks free of his reins, and heads towards the flames. Dan is struggling with a way to save Johnny and June when Bullet shows up.

Dan knows a way to save the couple. He mounts Bullet, rides through the flames, arrives at the spot, and starts throwing ropes around the safe. Dan then urges Bullet to pull the safe free. Bullet frees Johnny and June.

Scene switches to a farmhouse in the country. Dan finds out that Dr. Rutherford has bought a small farm with enough pasture to take care of all the fire horses; Dan will become the caretaker. It fades out with Dan holding Bullet.[3]

Cast

The cast of this film used several of the same actors who appeared in In the Name of the Law.[4]

Actor Role Ralph Lewis Dan McDowell Johnnie Walker Johnny McDowell Ella Hall June Rutherford Virginia True Boardman Mother McDowell Frankie Lee Little Jimmie Wilbur Higby Fire Chief Andrews Richard Morris Dr. Rutherford Josephine Adair Alice McDowell Bullet a Fire Horse

Production

Development

While standing on a street corner in downtown Los Angeles, Emory Johnson and his mother watched the annual Elk 's parade. Apart from the parade, the pair was struck by the appearance of the LAPD 's fire horses. This parade would be the fire horse's last appearance in public. The horses had all been replaced by motorized vehicles. All were retired from service and put out to pasture. But to the Johnson's, the fire horses represented a small part of a broader canvas.

It occurred to them; the horses symbolized a changing of the guard. The idea for a motion picture took root.[5]

Director Emory Johnson, [6]

Themes

Like the director's quote, love and devotion are constant themes interwoven throughout the fabric of the third alarm's storyline. Dan McDowell's devotion to his wife and likewise her devotion to him; the couple's everlasting love and willingness to sacrifice for their children; Johnny's love for June; Dr. Rutherford's fatherly love for his daughter; Dan devotion for the horses in his care; a crippled boy kindness. All of these were carefully blended to complement the tale of our working-class hero and create another Emory Johnson Melodrama. Moviegoers often saw another central theme.

Dan McDowell's plight when he is caught between one of life's passages - too old to be young yet not old enough to be old. Mechanization had taken away the job he loved and changed the way he lived. This theme was something so many working class individuals could relate to in the industrial age.

First, he paid homage to the police officers, and now he would honor the firefighters. Like the Patrick O'Hara character in "In the Name of the Law," this movie portrays firemen as family men trying to balance raising a family with the dangerous profession of firefighting. Johnson felt both these working-class heroes did not get the recognition they so richly deserved for the work they did. Emory Johnson's glorification of public servants would become the perfect subject material for all of his F.B.O. Special productions.

Screenplay

Writer Emilie Johnson, [7]

Emilie Johnson was Emory Johnson 's mother. She was born on June 3, 1867, in Gothenburg, Västra Götaland, Sweden. Her only son was born in 1894 - Alfred Emory Johnson.[8]

In the 1920s, Emilie and Emory Johnson would develop one of the unique relationships in the annuals of Hollywood. The decade saw the mother-son team develop into the most financially successful directing and writing team in motion picture history. Their unique collaboration would persist through the decade only fading in the early 30s. Such collaborations in Hollywood have been few and far between. She wrote most of the stories and screenplays her son used for his prosperous career in directing melodramas.

Emilie discussed The Third Alarm with the newspaper - "When creating The Third Alarm, I took every possible opportunity to visit the engine houses of the fire department, watching the actions of the firemen and observing the procedure in answering an alarm. Emory is always with me on these occasions, and we are in consultation daily in regard to angles of the story that present themselves as a result of our observations. Together we attend the fire chiefs convention and San Francisco." [9]

Pre production

A real estate dealer misfortune allowed Emory Johnson's to purchase a five-story apartment building on the outskirts of Los Angeles for a reasonable price. The city had condemned the building as a fire trap. To film the burning-building sequences in The Third Alarm, the building was set ablaze. The fire was under the Los Angeles fire department's supervision and used a dozen companies of professional firefighters and scores of equipment.[10]

Emory Johnson would shoot this movie on location in Los Angeles, California. The studio location, coupled with the fact that LAFD was the largest fire department globally, had a sizable contingent of retired fire horses and would allow the use of scrapped steam fire engines in the movie lent itself to a symbiotic relationship. In 1911, the LAFD had 25 horse-drawn steam fire engines and 163 horses. 1911 was the last year they remained in service and the first year of motorized apparatus on the LAFD. The phase-in of motorized equipment would continue until the last fire horse was retired in 1921.[11]

To make his production as accurate and authentic as possible, Emory Johnson pointed out - "I lived for several weeks among the firemen of Los Angeles to get the color and atmosphere for my production."[12]

Filming

This movie was filmed on location entirely in Los Angeles, California and had the complete cooperation of the Los Angeles Fire Department. The LAFD furnished equipment, old-style firefighting apparatus, and large firefighting workforce to assist Emory Johnson in making this movie.[13]

Schedule

The Shooting Schedule according to Camera! "Pulse of the Studios" section:

- Principal photography on the The Discard begins the first week of July 1922.[14]

- Film editing on the "The Discard" was started in late August 1922.

- The Discard was listed as "Complete" in September 1922.

- The title of the film was changed between September and October.

- The Third Alarm returned to Film editing in October 1922.

- The Third Alarm drops out of "Pulse of the Studios" on October 16, 1922.[15]

Alternate title

Based on the Camera! shooting schedule, the title of the film "The Discard" was changed to The Third Alarm between September and October 1922.[14][15]

The title "The Discard" is sometimes confused with its companion film In the Name of the Law. An alternate title for In the Name of the Law is incorrectly listed on some websites as "The Discard" or "Discard". The mix-up occurred because filming started on "The Discard" in July 1922. This date would coincide with the July 9 premiere of "In the Name of the Law".

Post production

Actor Ralph Lewis[16]

F.B.O. rewarded Ralph Lewis for his work in In the Name of the Law, The Third Alarm (1922 film) and The West~Bound Limited by placing him under a long-term contract in April 1923.[17]

This film is the second production under Emory Johnson's F.B.O. Contract. Johnson would claim in May 1932, he made "that picture for $40,000 (equivalent to $610,974 in 2019) and it grossed one million two hundred thousand (equivalent to $18,329,225 in 2019)."[18] The film would become the most financially successful movie ever produced in Emory Johnson's career. The movie earned Johnson an estimated $275,000 (equivalent to $4,200,447 in 2019).[19]

Emory Johnson would move on to start working on his next film - The West~Bound Limited released in April 1923. This film would feature a train engineer and once again star Ralph Lewis. In the years to come, Johnson would glorify mail carriers, newspaper press operators, more train engineers, police officers, Army aviators, and members of the US Navy.

Music

In January 1923, a new Fireman's song by Johnnie Tucker was copyrighted.[20] In April 1923, Okeh Records cut a recording by the Fire Department of New York and Rega Dance Orchestra. The song was composed by Johnnie Tucker with lyrics by Bartley Costello and featured John Stewart, a boy soprano singing "A fire laddie (just like my daddy)."[21][22] The composer, John Tucker, had been an officer of the New York Fire Department for several years. He played both trombone and piano for the Fireman's Quartet, and due to his background, he composed the song for the motion picture The Third Alarm.[23]

Advertising

In August 1922, a convention of the International Association of Fire Engineers was held in San Francisco. During the convention, the fire chiefs were introduced to director Emory Johnson and his wife, Ella Hall. Emory and Ella were promoting a new film titled The Third Alarm. The film was still being edited, but Emory Johnson was able to show two reels of the film to assembled chiefs. The chiefs were impressed with the film's accuracy in depicting firefighting techniques. This was the first promotion of the film four months before the actual release date.[24] F.B.O. implemented the same advertising strategy they used in promoting In the Name of the Law. Before this film was released, FBO stated it had 100 letters from fire chiefs around the country. The chiefs stated they would fully support the showing of this film in their cities.

In the world of film, the word exploitation has devious connotations. However, there is a vast difference between an Exploitation film and exploiting a film. In the 1920s, the F.B.O. concept of film exploitation meant creating local tie-ins with the particular working-class or public servants portrayed in the film. In the case of The Third Alarm, it meant establishing contact with the fire department in the local venue before the film was even scheduled to arrive in the city. An F.B.O. agent, if available, and the theater owner would work hand-in-hand in developing an exploitation strategy for the film. This usually meant developing a relationship with the local fire chief. In turn, the chief would realize the benefits of promoting the movie and go on record with his endorsement. This support could include the chief's speaking to local newspapers and providing fire equipment to attract paying patrons to the movie theater.[25]

Many local Fire departments gave the movie free advertising by staging various displays. A typical example of this promotion is dusting off old firefighting apparatuses, hitching up horses and clamoring down the street, bells clanging, and ending at the local theater. Small crowds might follow the equipment to the theater, hoping to catch a glimpse of the fire. [26] Other stunts might include parking old museum pieces in front of the theater, appreciation parades, and women jumping off buildings. Anything thing was fair game if it drew potential movie ticket purchasers to the work of local firefighters and built up a need to see them in action on the silver screen. Another strategy to get the firefighters on board with the advertising was to donate a portion of each ticket price to the fireman's pension fund. This was the same scheme used in In The Name of the Law.

If the theater owners had questions on exploiting this movie, FBO would provide a 22-page newspaper size campaign book. (See Campaign book pictured above)[27] As the article stated, hundreds of these were mailed out while the movie was still premiering at the Astor Theatre.

Release and reception

Several websites assert the first showing of the film was in Cleveland, Ohio, on December 25, 1922.[28] These references are based on American Film Institute listing[29] and confirmed by a movie advertisement in the Cleveland's The Plain Dealer.[30] Other references state the promotional materials for the film wouldn't be ready until the first week in January 1923.

On December 31, 1922, the film was copyrighted to R-C (Robertson-Cole) Pictures Corp with a registration number of LP18553. The copyrights for FBO Films were registered with their original British owners. FBO was the official name of the film distributing operation for Robertson-Cole Pictures Corp. Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. would clear this up later[31]

Official release

The film was officially released on January 7, 1923, by Film Booking Offices of America.[32]

New York premiere

Film Booking Offices of America booked The Third Alarm into prestigious 1,131 seats Astor Theatre in New York City for a four-week run starting on Sunday, January 7, 1923. This was a huge investment for F.B.O. This "Theatrical Rental Arrangement" cost F.B.O. $6,000 (equivalent to $91,646 in 2019) a week to rent the theatre.

According to Variety, ticket prices for the Astor performances ranged from $1.00 for matinee and $1.50 for evenings (Normal prices for the Astor). The magazine also observed the four-week run was generally a success. The first week generated $7,800, "including a tie-up with the fire department for the pension fund." [33] For the third week, Variety stated - "Not pulling, but being run for the advertising that it gets." [34] The last week, the magazine stated "Forth, and final week, the picture just got by, doing something less than the general expense of the house and advertising. little under $5,000.[35] F.B.O. presented a more nuanced view of the New York run touting the run as a resounding success.[36]

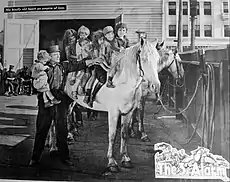

Grauman Los Angeles

On Monday, January 29, 1923, a Los Angeles Fire Department engine clanged up and down the thoroughfares, finally stopping at Sid Grauman Million Dollar Theater on Broadway. The theater had a capacity of 2,345 seats. The people following the engine soon discovered the advertising ploy was directing people to watch the movie house's latest feature – The Third Alarm. Sid Grauman had rented the blockbuster film for two weeks. The fire engine stunt would be used effectively across the country to advertise the film, always with the local fire department's full cooperation. The promotional photograph on the right shows Emory Johnson supporting his film showing at the Sid Grauman Million Dollar Theater in Los Angeles.[37]

The film then continued to be shown in theaters across the country. Of the hundreds of moviehouse reviews published in the film magazines of the time, hardly a negative review can be found.

Reviews

In the Film Year Book 1922-23 (The 1922-23 Film Daily Year Book of Motion Pictures) The Third Alarm is named one of the "The Forty Best Pictures of the Year" as "Selected by the National Board of Review of Motion Pictures, from productions reviewed from December 1921 to December 1922." [38]

Critical response

The movie received positive reviews. Most small-town and large city venues enjoyed the movie. After all, played at the Astor for over four weeks.

In the January 14, 1923 issue of the The Film Daily, the reviewer points out[39]

An almost inexhaustible supply of fine thrills in a picture dedicated to firefighters; sure-fire box office picture of its kind.

There is a very definite box office value in the picture because it supplies a new line of thrills and the sort of action and atmosphere that will certainly make it a popular number with the big majority of picture goers throughout the country

In the January 20, 1923 issue of the Exhibitors Trade Review, the reviewer states[40]

A stirring melodrama, replete with heart interest, whirling action, and stark realism, "The Third Alarm" registers as a unique attraction destined to win widespread popularity. That photography is immense, goes without saying. The shots of fighting the flames are of quality that entitles the cameraman to unstinted credit, better stuff of its kind has never been screened.

The picture fairly throbs with spectacular views, the brigade swinging with frantic, Furious speed through the streets, fire laddies battling desperately against the devouring elements, the red blaze bursting across surging banks of smoke, walls tottering and crashing. . .

In the February 1, 1923 issue of the San Antonio Evening News, Mary Carter observes[41]

The Third Alarm is the most thrilling motion picture the writer ever saw. It glorifies and immortalizes the noble instincts of the American firemen; shows the fine traditions of the American fire department, the dangers of a fireman's life, and bestows in everlasting benediction upon the wives and the daughters of firefighters. The faithful fire horses are not forgotten in this amazing and gripping photoplay.

Audience response

FBO focused on producing and distributing films for small-town venues. They served this market melodramas, non-Western action pictures, and comedic shorts. These moviehouse reviews were critical for a distributor like FBO. Unlike many of the major Hollywood studios, FBO did not own their own set of theaters. Like most independents, FBO was dependent on the moviehouse owners to rent their films for the company to show a profit.

These are brief published observations from moviehouse owners. Theater owners would subscribe to the various movie magazines, read the movie critic's reviews, then read the theater owner's reports. These reviews would assist them in deciding if the film was a potential moneymaker in their venue.

J.S. Rex, Princess Theatre Wauseon, Ohio population 8,000[42]

THE THIRD ALARM, with a special cast. - This is the best picture I have ever shown. Could not handle all the people. Ran two days to the largest crowd in the history of theatre.

George K. Zimsz, Harbor Theatre Corpus Christi, Texas population 10,000[43]

Star, cast. Darn good picture. Patrons went out, saying, "That's what I call a picture." Rotten print, but made it do. Used Fire department Run, usual paper, and lobby. Had fair attendance. Draw all classes. Admission 10-20-30

Harold Frank Mgr, Majestic Colonial Theatre Jackson, Michigan population 50,000[44]

The Third Alarm opened here today to the biggest weekday business this house has ever known, and we've played all the big ones. The crowd standing out till after 9:30 PM Greatest exploitation picture I have ever seen

Preservation status

Martin Scorsese

filmmaker, director NFPF Board

A report created by film historian and archivist David Pierce for the Library of Congress claims:

- 75% of original silent-era films have perished.

- 14% of the 10,919 silent films released by major studios exist in their original 35mm or other formats.

- 11% survive in full-length foreign versions or on film formats of lesser image quality.[45][46] Many silent-era films did not survive for reasons as explained on this Wikipedia page.

Emory Johnson directed a total of 13 films, of which 11 were silent, and 2 were talkies. The Third Alarm was the second film in Emory Johnson's eight-picture contract with FBO. According to the Library of Congress website, this film has a status of - "incomplete copies of this film exist in Gosfilmofond Of Russia Moscow, UCLA Film and Television Archive Los Angeles."[47] Other web sites claim complete copies exist at the UCLA Film and Television Archive in Los Angeles.[48]

Author John Reid in his book, states, "By cobbling together the best footage from multiple 16mm prints", a restoration service was able to assemble a tinted presentation of the film. He also claims "sources differ as to whether the original theatrical version had six or seven reels." He further went on to observe, "the five-reel Kodascope cutdown was one of the library's most popular movies. This five-reel version is now available on DVD . . . "[49]

Reid also discusses the controversy regarding the length of the original theatrical release of the film. The Library of Congress's publication - Catalog of Copyright Entries shows two entries:[31]

- THE THIRD ALARM. Released thru Film Booking Offices of America 1922 6 reels copyright R-C Pictures Corp.; December 31, 1922 LP18553

- THE THIRD ALARM. 1930 7 reels, copyrighted Tiffany Productions, Inc.; November 28, 1930 LP1775

The entry in the Performing Arts Database of the Library of Congress states - 7 reels; 6.700 ft.[47] as does the "AFI CATALOG OF FEATURE FILMS." [1] The restored versions available on YouTube run between 57 – 59 minutes i.e. approximately 5 reels (11 minutes per reel). Thus, the restored versions are missing minutes present in the film's original theatrical release. The exact time difference between the original release and the restored version is lost to time, but the main story points have survived.

The restored film is in the public domain and available on YouTube. The film is also available on DVD and is widely available from multiple vendors.

Gallery

- Principal Players and Directer

Virginia True Boardman

Virginia True Boardman

Mother McDowell Ralph Lewis

Ralph Lewis

Dan McDowell Johnnie Walker

Johnnie Walker

Johnny McDowell Ella Hall

Ella Hall

June Rutherford Richard Morris

Richard Morris

Dr. Rutherford Josephine Adair

Josephine Adair

Alice McDowell Frankie Lee

Frankie Lee

Little Jimmie Wilbur Higby

Wilbur Higby

Fire Chief Andrews Bullet

Bullet

The fire horse Emory Johnson

Emory Johnson

Director

- Movie Stills and Lobby Cards

_lobby_card_2.jpg.webp) The Third Alarm

The Third Alarm

Lobby Card The Third Alarm

The Third Alarm

Lobby Card The Third Alarm

The Third Alarm

Motion Picture News

See also

References

- The Third Alarm at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Progressive Silent Film List: The Third Alarm at silentera.com

- "The Third Alarm: F.O.B. Photoplay in Seven Parts". Exhibitor's Trade Review. East Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania: Exhibitor's Trade Review, Inc. 13 (8): 423. January 20, 1923.

- "Fireman Picture Presented by F.B.O." Motion Picture News. October 21, 1922. p. 2013.

- "Find Idea in Horses' Last Run". The Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles, California). February 4, 1923 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Love best theme for films, Emery Johnson Says". Detroit Free Press (Detroit, Michigan). July 15, 1923. p. 73 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Plays and Players". Stamford Daily Advocate. October 18, 1924. p. 16 – via GenealogyBank.com.

- "This Writer has Produced 19 Scenarios". Riverside Independent Enterprise. May 14, 1922. p. 5. Retrieved February 2, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Visit railroad shops in search of local color". The Butte Miner (Butte, Montana). June 17, 1923. p. 10 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Nero fiddled? No, crank turned in apartment fire". Daily News (New York, New York). January 6, 1923. p. 17 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Los Angeles Firemen's Relief Association - LAFD History - Fire Horses". April 30, 2014. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "Screen - Firemen Have Slang". Medford Mail Tribune (Medford, Oregon). January 23, 1923. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Real Estate Tragedy is Great Film Opportunity". Times-Advocate (Escondido, California). September 7, 1923. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Pulse of the Studios". Camera!. July 15, 1922. p. 10.

- "Pulse of the Studios". Camera!. October 14, 1922. p. 13.

- "At Dixie No. 1". The Galveston Daily News (Galveston, Texas). April 7, 1923. p. 2. Retrieved May 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Film Mart - F.B.O." Exhibitors Herald. April 28, 1923. p. 475.

- "Producer Says Best Films are Full of Hokum". The Rock Island Argus (Rock Island, Illinois). May 2, 1932. p. 15. Retrieved May 2, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Famed Movie Producer Lives Quietly in S.M. He Loves". The Times (San Mateo, California). July 25, 1959. p. 21 – via GenealogyBank.com.

- "Renewal Registrations". U.S. Govt. Print. Off. 1950.

- "Discography of American Historical Recordings, s.v. "OKeh matrix S-71459. A fire laddie (Just like my daddy) / Fire Department of New York Quartet ; Rega Dance Orchestra,"". 1923. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- Ross Laird; Brian A. L. Rust; Brian Rust (2004). Discography of OKeh Records, 1918-1934. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-313-31142-0.

- Ken Wlaschin (2009). The Silent Cinema in Song, 1896-1929: An Illustrated History and Catalog of Songs Inspired by the Movies and Stars, with a List of Recordings. McFarland & Company. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-7864-3804-4.

- "THE THIRD ALARM - Manager Salzwedel Offers a First Class Picture for Benefit of Firemen's Fund". The Chicago Heights Star (Chicago Heights, Illinois). January 11, 1923. p. 1. Retrieved May 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Demonstration is Given by Firemen - Chief Fred Martin Recommends Picture; "The Third Alarm" to Butte's Public". The Butte Miner(Butte, Montana). February 25, 1923. p. 1. Retrieved May 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "THE THEATRE - A Department of practical showmanship". Exhibitors Herald. March 3, 1923. p. 1155.

- "Cover of the striking campaign book". Exhibitors Herald. February 3, 1923. p. 40.

- The-Third-Alarm Film about firemen at the TCM Movie Database

- Kenneth White Munden; American Film Institute (1997). The American Film Institute Catalog of Motion Pictures Produced in the United States. University of California Press. p. 799. ISBN 978-0-520-20969-5.

- "Plays and Players". Plain Dealer (Cleveland, OH). December 25, 1922. p. 19 – via GenealogyBank.com.

- "Catalog of Copyright Entries Cumulative Series Motion Pictures 1912 - 1939". Internet Archive. Copyright Office * Library of Congress. 1951. p. 868. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

Motion Pictures, 1912-1939, is a cumulative catalog listing works registered in the Copyright Office in Classes L and M between August 24, 1912 and December 31, 1939

- "Silent Era: Progressive Silent Film List". www.silentera.com.

- "Good Nights-Lights Mats on Broadway Last Week". Variety. January 19, 1923. p. 139.

- "Nothing Startled Broadway in Pictures Last Week". Variety. January 25, 1923. p. 187.

- "Broadway House Last Week Set New Gross Record". Variety. February 8, 1923. p. 91.

- "The Film Mart". Exhibitors Herald. February 17, 1923. p. 960.

- "How Pictures are Exploited". Picture-Play Magazine. August 1923. p. 683.

- "The Forty Best Pictures of the Year". The 1922-23 Film Daily Year Book of Motion Pictures. 1923. p. 350.

- "Fire climax offers a thrill with a real wallop". Film Daily. January 14, 1923. p. 2.

- "F.B.O. photoplay in seven parts". Exhibitor's Trade Review. January 20, 1923. p. 423.

- "Great photoplay immortalizes noble instinct of American fireman". San Antonio Evening News San Antonio, Texas. February 1, 1923. p. 11. Retrieved May 1, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- "What the Picture Did For Me". Exhibitors Herald. February 10, 1923. p. 75.

- "Straight From The Shoulder Reports". The Moving picture world. May 19, 1923. p. 189.

- "F.B.O. movie advertisement". Exhibitors Herald. March 3, 1923. p. 1191.

- Pierce, David. "The Survival of American Silent Films: 1912-1929" (PDF). Library Of Congress. Council on Library and Information Resources and the Library of Congress. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- Slide, Anthony (2000). Nitrate Won't Wait: History of Film Preservation in the United States. McFarland. p. 5. ISBN 978-0786408368. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

It is often claimed that 75 percent of all American silent films are gone and 50 percent of all films made prior to 1950 are lost, but such figures, as archivists admit in private, were thought up on the spur of the moment, without statistical information to back them up.

- The Library of Congress American Silent Feature Film Survival Catalog: The Third Alarm

- The Third Alarm at IMDb

- John Howard Reid (August 14, 2015). Silent Movies Plus! More Silent Films & Early Talkies on DVD. Lulu.com. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-329-41424-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Third Alarm (1922 film). |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lobby cards of the United States, 1922. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Emory Johnson. |

- Synopsis at AllMovie

- "The Third Alarm (1922)" on YouTube

- Sherwood, Robert (January 1, 1974). The best moving pictures of 1922-23, also Who's who in the movies and the Yearbook of the American screen. Revisionist Press. ISBN 978-0877001362.

- "Los Angeles Firemen's Relief Association - LAFD History - Fire Horses". April 30, 2014.