Smokejumper

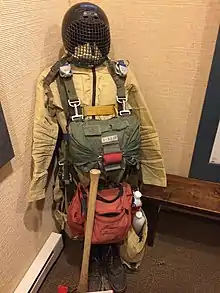

Smokejumpers are specially trained wildland firefighters who provide an initial attack response on remote wildland fires. They are inserted at the site of the fire by parachute.

In addition to performing the initial attack on wildfires, they may also provide leadership for extended attacks on wildland fires. Shortly after smokejumpers touch ground, they are supplied by parachute with food, water, and firefighting tools, making them self-sufficient for 48 hours. Smokejumpers are usually on duty from early spring through late fall.

Smokejumpers worldwide

Smokejumpers are employed by the Russian Federation, United States (namely the United States Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management), and Canada (in British Columbia).[1]

History

Prior to the full establishment of smokejumping, experiments with parachute insertion of firefighters were conducted in 1934 in Utah and in the Soviet Union. Earlier, aviation firefighting experiments had been conducted with air delivery of equipment and "water bombs". Although this first experiment was not pursued, another began in 1939 in Washington's Methow Valley, where professional parachutists jumped into a variety of timbered and mountainous terrains, proving the feasibility of the idea.

Smokejumping was first proposed in 1934 in the Intermountain Region (Region 4), by Regional Forester T.V. Pearson. By 1939, the program began as an experiment in the Pacific Northwest Region (Region 6). The first official non-fire jump was made in the Nez Perce National Forest in the Northern Region (Region 1) in 1940 by John Furgurson and Lester Gohler. The McCall smokejumper program was established in 1943; their base is on the Idaho shores of Payette Lake. The base is near six national forests: Nez Pearce/Clearwater, Sawtooth, the Boise, Payette, Salmon-Chalis, and Wallowa-Whitman. In 1947, the McCall program trained 50 jumpers and completed the construction of new buildings and training facilities. In 1941, the first women successfully completed the training program at the McCall program.[2]

In 1942, permanent jump operations were established at Winthrop, Washington, and Ninemile Camp, an abandoned Civilian Conservation Corps camp (Camp Menard) a mile north of the Forest Service's Ninemile Remount Depot (pack mule) at Huson, Montana, about 30 miles northwest of Missoula. The first fire jumps were made by Rufus Robinson and Earl Cooley at Rock Pillar near Marten Creek in the Nez Perce National Forest on July 12, 1940, out of Ninemile, followed shortly by a two-man fire jump out of Winthrop. In subsequent years, the Ninemile Camp operation moved to Missoula, where it became the Missoula Smokejumper Base. The Winthrop operation remained at its original location, as North Cascades Smokejumper Base. The "birthplace" of smokejumping continues to be debated between these two bases, the argument having persisted for about 70 years.

The first smokejumper training camp was at the Seeley Lake Ranger Station, over 60 miles northeast of Missoula. The camp relocated to Camp Menard in July 1943. Here, when not fighting fires, the men spent much time putting up hay to feed the hundreds of pack mules that carried supplies and equipment to guard stations and fire locations. To work fires, the men, organized into squads of eight to 15, were stationed at six strategic points, also known as "spike camps": Seeley Lake, Big Prairie, and Ninemile in Montana; Moose Creek and McCall in Idaho; and Redwood Ranger Station in southwestern Oregon at the edge of Cave Junction. The men worked from other spike camps, as well, including some in Washington.

Relations with the military

After observing smokejumper training methods at Seeley Lake in June 1940, then-Major William C. Lee of the U.S. Army went on to become a major general and establish the 101st Airborne Division.

In May 1978, members of the Army National Guard's 19th Special Forces Group (Airborne) and other western military units briefly began airborne training at the Missoula Smokejumper School. Although in years past, the army had conducted basic airborne training at various locations, it has since been consolidated at Fort Benning, Georgia.

WWII-era

The 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion gained fame as the only entirely black airborne unit in United States Army history. The 555th was allegedly not sent to combat because of segregation in the military during World War II. In May 1945, the unit was sent to the West Coast of the United States to combat forest fires ignited by Japanese incendiary balloons, an operation named "Operation Firefly". Although this threat did not fully materialize, the 555th fought numerous other forest fires while there. Stationed at Pendleton Field, Oregon, with a detachment in Chico, California, 300 unit members participated in firefighting missions throughout the Pacific Northwest during the summer and fall of 1945, earning the nickname "Smoke Jumpers". The 555th made a total of 1,200 jumps to 36 fires, 19 from Pendleton and 17 from Chico. Only one member, PFC Malvin L. Brown, was killed on August 6, 1945, after falling during a let-down from a tree in the Umpqua National Forest near Roseburg, Oregon. His death is the first recorded smokejumper fatality during a fire jump.

Around 240 workers from Civilian Public Service (CPS) camps worked as smokejumpers during World War II. An initial group of 15 men began training in parachute rigging in May 1943 at Seeley Lake, and a total of 33 completed jump training in the middle of June, followed by two weeks of training in fire ground control and first aid. About 500 training jumps were made by the first 70 CPS smokejumpers in 1943, who went on to fight 31 fires that first season. Their number increased to 110 in 1944, and to 220 in 1945, as more equipment became available from the War Department. Twenty-nine jumpers battled the remote Bell Lake fire in September 1944, among 70 fires suppressed that year, and 179 were fought in the Missoula Region alone by September 1945, with other jumpers assigned to McCall and Cave Junction. The last CPS smokejumper left the service in January 1946.

The Smokejumper Project had become a permanent establishment of the USFS in 1944. In 1946, the Missoula Region had 164 smokejumpers, many of them recent military veterans, college students, or recent college graduates. New bases were opened in Grangeville, Idaho, and West Yellowstone, Montana.

Most smokejumpers of the era were not career professionals, but seasonal employees lured by the prospect of earning as much as $1,000 over a summer. They tended to be well-behaved, self-motivated, and responsible. Squad-sized and larger crews were supervised by foremen who were career wildland firefighters and experts in all types of wildfires.

Mann Gulch Fire

The fire with the greatest toll of smokejumper deaths was the Mann Gulch fire in 1949, which occurred north of Helena, Montana, at the Gates of the Mountains area along the Missouri River. Thirteen firefighters died during the blowup, 12 of them smokejumpers. This disaster directly led to the establishment of modern safety standards used by all wildland firefighters. Author Norman MacLean described the incident in his book Young Men and Fire (1992).

Safety record

Despite the seemingly dangerous nature of the job, fatalities from jumping are infrequent, the best-known fatalities in the United States being those that occurred at the Mann Gulch fire in 1949 and the South Canyon Fire in 1994.

Jump injuries are infrequent, and smokejumper personnel take deliberate precautions before deciding whether to jump a particular fire. Multiple factors are analyzed, and then a decision is made as to whether jumping the fire is safe. Bases tend to look for highly motivated individuals who are in superior shape and have the ability to think independently and react to changing environments rapidly. Many smokejumpers have previous experience as hotshots, who provide a strong foundation of wildland firefighting experience and physical conditioning.

Smokejumper crews

Today, nine smokejumper crews operate in the United States. Seven are operated by the United States Forest Service (USFS), and two are operated by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

Operated by the United States Forest Service:

- Northwest - the Redmond Smokejumpers in Redmond, Oregon. the North Cascades Smokejumpers in Winthrop, Washington.

- Northern California -the Region 5 Smokejumpers in Redding, California.

- Northern Rockies - the Missoula Smokejumpers in Missoula, Montana. the Grangeville Smokejumpers in Grangeville, Idaho. the West Yellowstone Smokejumpers in West Yellowstone, Montana.

- Great Basin - the McCall Smokejumpers in McCall, Idaho.

Operated by the Bureau of Land Management:

- Great Basin - the Boise Smokejumpers in Boise, Idaho.

- Alaska - the Alaska Smokejumpers in Fort Wainwright, Alaska.

The British Columbia Wildfire Service Parattack program operates the only smokejumper crews in Canada. There are two crews located in the northeast of the province.[3]

- The North Peace Smokejumpers in Fort Saint John, British Columbia.

- The Omenica Smokejumpers in Mackenzie, British Columbia.

Physical fitness

The minimum required physical fitness standards for smokejumpers set by the National Wildfire Coordinating Group are: packout 110 pounds for three miles within 90 minutes; run 1.5 miles in 11 or fewer minutes; 25 push-ups in 60 seconds; 45 sit-ups in 60 seconds; and seven pull-ups.[4]

In popular culture

- The 1952 film Red Skies of Montana is based in part on the 1949 Mann Gulch disaster.

- In the television show Entourage, Vincent Chase lands a lead role in an action film called Smokejumpers.

- Author Nora Roberts's April 2011 novel Chasing Fire is set among the "Zulies" of the Missoula Smokejumper Base.

- Author M. L. Buchman's Smokejumper trilogy in his Firehawks series follows a team of fictitious Oregon-based smokejumpers.

- Smokejumpers are featured in the 1985 novel Wildfire by Richard Martin Stern, the 1989 Steven Spielberg film Always, the 2002 made-for-television movie SuperFire, and the 1998 film Firestorm, the latter two of which were critically panned for their wild inaccuracies in depicting the profession. Smokejumpers are described in Philip Connor's 2011 book Fire Season.[5] Author Nora Roberts's 2011 novel Chasing Fire also details the lives and loves of a group of smokejumpers.

- The 1996 film Smoke Jumpers is loosely based on Don Mackey's life. Mackey was a smokejumper and one of the 14 fatalities on the 1994 South Canyon fire. In the movie, he pursues job-related accolades while his marriage disintegrates.

- In the 2008 TV movie Trial By Fire, Kristin Scott attempts to join the smokejumpers after her father's death in a house fire a day before he retired from duty.

- The Disney film Planes: Fire and Rescue, includes Regina King, Corri English, Bryan Callen, Danny Pardo, and Matt L. Jones, who play smokejumpers based out of Piston Peak Air Attack Base.

- Alaska smokejumpers were featured in the 2015 Weather Channel documentary Alaska: State of Emergency, hosted by Dave Malkoff.

- The lead character in Marlow Briggs and the Mask of Death, a video game developed by ZootFly and Microsoft Studios, is a smokejumper.

- The 2019 American family comedy film Playing with Fire follows a group of smokejumpers who must watch over three children who have been separated from their parents following an accident. The film stars John Cena, Keegan-Michael Key, John Leguizamo, Brianna Hildebrand, Dennis Haysbert, and Judy Greer.[6]

See also

References

- "The Canadian Smokejumper". smokejumper.ca. Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- "History of Smokejumping | US Forest Service". www.fs.fed.us. Retrieved 2019-05-03.

- "Location | The Canadian Smokejumper". smokejumper.ca. Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- Brian J. Sharkey, Ph.D.; Steven E. Gaskill, Ph.D. "Ch. 6". Fitness and Work Capacity (PDF) (2009 ed.). National Interagency Fire Center, Boise, I D.: National Wildfire Coordinating Group. p. 27.

Smokejumpers: Pack Test: Req.; 3-Mile Packout Weight: Rec-110; 1.5-Mile Run time: Rec-11:00; 10 RM Leg Press: 2.5xBW; 10 RM Bench Press: 1.0xBW; Pullups: 7; Pushups: 25; Situps 45

- BBC Radio 4 - Book of the Week, Fire Season, Episode 1

- Playing with Fire, retrieved 2020-02-06

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Smokejumpers. |

- California Smokejumpers Official Site.

- National Smokejumper Association (USA), including history

- US Forest Service - National Interagency Smokejumper Training Guide, including history (in PDF format)

- CPS Unit Number 103-01, World War II Smokejumpers

- Smokejumpers and Smokejumping: Information and Photos

- Spotfire Images: Quality Smokejumper and Fire Photos.

- Earl Cooley - Daily Telegraph obituary

- US Forest Service list of smokejumper bases

- Nick Sundt Smokejumpers Oral History Project (University of Montana Archives)

- Civilian Public Service Smokejumpers Oral History Project (University of Montana Archives)