Tibet-India relations

India–Tibet relations are said to have begun during the spread of Buddhism to Tibet from India during the 7th and 8th centuries AD. In 1959, the Dalai Lama fled to India after the failed 1959 Tibetan uprising. Since then, Tibetans-in-exile have been given asylum in India, with the Indian government accommodating them into 45 residential settlements across 10 states in the country. From around 150,000 Tibetan refugees in 2011, the number fell to 85,000 in 2018, according to government data. Many Tibetans are now leaving India to go back to Tibet and other countries such as United States or Germany. The Government of India, soon after India's independence in 1947, treated Tibet as a de facto independent country.[1] However, more recently India's policy on Tibet has been mindful of Chinese sensibilities.

History

Scholars like Buton Rinchen Drub (Bu-ston) have suggested that Tibetans are descendants of Rupati, a Kaurava military general from the mythological Kurukshetra War.[2] Other scholars point to the spread of Buddhism to Tibet from India through the efforts of Tibetan kings, Songtsen Gampo and Trisong-Detsen as the first significant contact.[3] The 13th Dalai Lama, Thubten Gyatso, had visited the Indian subcontinent in 1910.[4] Today, Tibetan pilgrims visit Gaya, Sarnath and Sanchi, places that are connected to the life of Buddha.[5]

British Raj (1767–1947)

In 1779, the third Panchen Lama, was well disposed to East India Company agents from British India.[6] Treaties regarding Tibet were concluded between Britain and China in the 1880s and 1890s but the Tibetan government refused to recognize their legitimacy.[7]

A British expedition to Tibet, effectively an invasion, under the command of Brigadier-General James Macdonald and Col. Francis Younghusband began in December 1903 and lasted for around ten months.[8] Following this the convention between Great Britain and Tibet was signed in 1904; essentially the treaty imposed upon the Tibetans numerous points such as payment of a large indemnity to the British. This treaty was followed by a Sino-British treaty in 1906 in which the British agreed not to annex Tibet and China agreed "not to permit any other foreign state to interfere with the territory or internal administration of Tibet".[9]

The Qing sent a military expedition to Tibet in 1910, Lhasa was occupied,[10] and the Dalai Lama had to flee to British India, where he stayed for around three years.[11] During 1904–1947, over 100 British-Indian officials lived and worked in Tibet.[12]

Independent India (1947–1956)

India had a diplomatic mission in Lhasa from 1947 onwards. However, in 1952 it was downgraded into a consulate general, and, after the 1962 Sino-Indian War, the consulate general was closed.[13] At the time, there were only three countries that had missions in Lhasa: Bhutan, Nepal and India; only Nepal's mission remains.[13] S. L. Chhibber was the Indian consul general in Lhasa from 1956 onwards followed by P. N. Kaul.[14] India has requested China over the years to allow the re-opening of a consulate in Lhasa; however, Beijing is unwilling.[15] In 2011, B. Raman wrote that India should not allow Beijing to open any more consulates in India unless India's long-standing demand of a consulate in Lhasa is accepted.[16]

Exile in India

The 14th Dalai Lama escaped from Tibet to India in March 1959 following the failed 1959 Tibetan uprising. On reaching India, the Chushi Gangdruk, who had assisted the Dalai Lama in his escape, handed over all their weapons to the Indian authorities.[17] Since 1959, for over 60 years, India has given exiled Tibetans shelter.[18] The Central Tibetan Administration (CTA), also known as the Tibetan government-in-exile, was formed in 1959 and is headquartered in Dharamshala, Himachal Pradesh, India.[19] In 1991 the CTA became a founding member of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO).[20] In 2009, a survey by the CTA recorded 94,203 Tibetan refugees in India.[21] The Indian government officially recognises Tibetans only as 'foreigners' and not as refugees.[22]

A CTA functionary said in 2019:[18]

China has occupied Tibet and we expect India has the only legitimacy and credibility to speak about Tibet [...] It is due to India's consistent generosity and kindness, we, the people in exile, have been able to preserve our ancient cultural heritage in exile

Tibetans in India have been accommodated by the Indian government in 45 residential settlements across 10 states in the country. There are 59 monasteries across India.[23] Tibetan children are provided free education, and seats are reserved for them in universities. However, they are not eligible for government jobs, and in some states they cannot get loans and are not allowed to drive.[24] Tibetans refugees in India cannot own land or property. In 2017, 60 years after coming to India, the Indian government permitted Tibetans to get passports.[25] In 2018 it was reported that many Tibetans are leaving India for better opportunities elsewhere, including Tibet.[26] From around 150,000 Tibetan refugees in 2011 the number fell to 85,000 in 2019, according to government data.[22][24] While some are going back to Tibet, other Tibetans are leaving India for countries such as United States and Switzerland.[22] In 2018, due to Chinese presence, India had shifted its stance with respect to Tibet, resulting in the Dalai Lama calling on Tibetans to stay united.[27]

Special Frontier Force

The Special Frontier Force (SFF), an elite commando unit formed in 1962 to conduct covert operations behind Chinese lines, consists of Tibetan refugees in India.[28][29] During the 2020 China–India skirmishes media reports emerged of the death of a Tibetan–Indian soldier of the SFF, Nyima Tenzin. On 8 September, images and videos appeared in the media of his public funeral and cremation with full state honors. His coffin was covered with both the Indian and Tibetan flags. However while media covered the event, the leadership in India remained silent.[30][31] Ram Madhav, who was seen at the funeral paying his respects, tweeted about the event, "Attended the funeral of SFF Coy Ldr Nyima Tenzin, a Tibetan who laid down his life protecting our borders in Ladakh, and laid a wreath as a tribute. Let the sacrifices of such valiant soldiers bring peace along the Indo-Tibetan border. That will be the real tribute to all martyrs." Ram Madhav later deleted his tweet.[32]

Tibet in India-China relations

The Government of India, soon after India's independence in 1947, made evident in its correspondence that it regarded Tibet as a de facto country.[1][lower-alpha 1] This was not unique to India, as Nepal and Mongolia also had treaties with Tibet. China had also considered Tibet an independent country.[5] A few months before India's independence, an Asian Conference was held in New Delhi. Tibet was invited and, along with the flags of other countries participating, Tibet's flag was flown. In 1949, following China's invasion of Tibet, India officially called the Chinese action "deplorable".[1] On 7 November 1950, India’s Deputy Prime Minister Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel wrote to the prime minister,[34]

The Chinese Government has tried to delude us by professions of peaceful intentions. My own feeling is that at a crucial period they managed to instil into our Ambassador a false sense of confidence in their so-called desire to settle the Tibetan problem by peaceful means. There can be no doubt that during the period covered by this correspondence, the Chinese must have been concentrating for an onslaught on Tibet. The final action of the Chinese, in my judgement, is little short of perfidy. The tragedy of it is that the Tibetans put faith in us; they chose to be guided by us; and we have been unable to get them out of the meshes of Chinese diplomacy or Chinese malevolence.

In 1954, China and India signed a trade agreement that would regulate the trade between the two countries with respect to Tibet.[35][36] This trade agreement ended India's centuries-old free trade with Tibet.[37] Bhimrao Ambedkar, India's first justice and law minister, said of the Panchsheel treaty in the Rajya Sabha, "I am indeed surprised that our Hon’ble Prime Minister is taking this Panchsheel seriously" and "by letting China take control over Lhasa (Tibet’s capital) the Prime Minister has in a way helped the Chinese to bring their armies on the Indian borders."[38] In 1962, following Chinese "betrayal" and aggression, Rajendra Prasad, the former first President of India, said at the Gandhi Maidan in October 1962,[39]

"Freedom is the most sacred boon. It has to be protected by all means — violent or non-violent. Therefore Tibet has to be liberated, from the iron grip of China and handed over to Tibetans"

.jpg.webp)

Acharya Kriplani said of Tibet in the Lok Sabha in 1959, "It was a nation which wanted to live its own life and it sought to have been allowed to live its own life. A good government is no substitute for self-government." Jaya Prakash Narayan had said "Tyrannies have come and gone and Caesars and Czars and dictators. But the spirit of man goes on forever. Tibet will be resurrected."[40] However, the Indian press commented on the silence of the government during the time and noted that the government could do little to help Tibet, even after a United Nations General Assembly resolution in 1961 that mentioned Tibet’s right to self-determination.[41] More recently, India's policy on Tibet has been based on trying not to offend China.[42]

Although Lobsang Sangay was invited to Prime Minister Modi's swearing-in ceremony in 2014 and the Chief Minister of Arunachal Pradesh declared that his state had a border with Tibet and not with China in 2017, a major shift in policy came in April 2018 after the Modi-Xi Jinping summit in Wuhan with the foreign ministry issuing a circular to dissuade government officials from going to Tibetan functions where the Dalai Lama or Tibetan government in exile were present.[43] All events marking the 60 years of the Tibetan government in exile were moved from New Delhi to Dharamshala.[32] During the 2020 border skirmishes and standoff between China and India, Shyam Sharan called "the tactical use of the Tibetan issue and of the Dalai Lama is both cynical and counter-productive"; he was referring to the use of the Special Frontier Force and the subsequent media coverage.[43] New Delhi was accused of using the Tibetans as a bargaining card only when tensions with China are high.[30]

Gallery

The 14th Dalai Lama in ceremonial dress enters India through a high mountain pass, Sikkim, 1956

The 14th Dalai Lama in ceremonial dress enters India through a high mountain pass, Sikkim, 1956 Prime Minister Nehru pointing out a landmark to the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama, 1956

Prime Minister Nehru pointing out a landmark to the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama, 1956 Dalai Lama visits the Kashmir Art Emporium at Calcutta, during his visit to the city, on January 21, 1957

Dalai Lama visits the Kashmir Art Emporium at Calcutta, during his visit to the city, on January 21, 1957 The Dalai Lama with President Rajendra Prasad and Vice President S Radhakrishnan

The Dalai Lama with President Rajendra Prasad and Vice President S Radhakrishnan The Dalai Lama, Nehru and Zhou Enlai in 1956 in India, at the UNESCO Buddhist Conference in Ashok Hotel, New Delhi.

The Dalai Lama, Nehru and Zhou Enlai in 1956 in India, at the UNESCO Buddhist Conference in Ashok Hotel, New Delhi. The Dalai Lama at Chou En-Lai’s side in 1956; Nehru is on the left

The Dalai Lama at Chou En-Lai’s side in 1956; Nehru is on the left Protest against China in India, 19 April 2008. Visible on left is Tibetan activist Tenzin Tsundue.

Protest against China in India, 19 April 2008. Visible on left is Tibetan activist Tenzin Tsundue. The 14th Dalai Lama in Dharamsala, 2012

The 14th Dalai Lama in Dharamsala, 2012 Mindrolling stupa at Dehradun

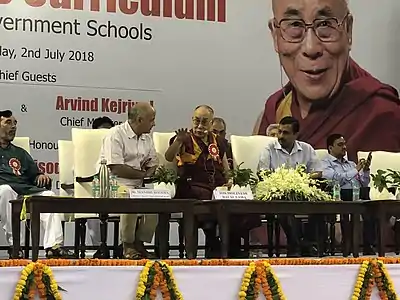

Mindrolling stupa at Dehradun Dalai Lama, Manish Sisodia and Arvind Kejriwala at the launch of the Happiness Curriculum, 2018

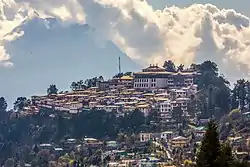

Dalai Lama, Manish Sisodia and Arvind Kejriwala at the launch of the Happiness Curriculum, 2018 Tawang Monastery located in Tawang, Arunachal Pradesh. It the largest monastery in India and second largest in the world.

Tawang Monastery located in Tawang, Arunachal Pradesh. It the largest monastery in India and second largest in the world. Cham dance during Dosmoche festival in Leh Palace

Cham dance during Dosmoche festival in Leh Palace

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Relations of India and Tibet. |

Notes

- In this, independent India followed the British India's policy, e.g., "an informal memorandum from Foreign Secretary Eden which stated that since 1911 Tibet had enjoyed de facto independence and opposed Chinese attempts to reassert control".[33]

References

- Mehrotra 2000, p. 7.

- Mehrotra 2000, p. 1.

- Mehrotra 2000, p. 2.

- Mehrotra 2000, p. 14.

- Mehrotra 2000, p. 8.

- Frederick W. Mote, Imperial China 900–1800, Harvard University Press, 2003 p.938.

- "Tibet Justice Center – Legal Materials on Tibet – Treaties & Conventions Relating to Tibet". www.tibetjustice.org. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- McKay, Alex (2012). "The British Invasion of Tibet, 1903–04". Inner Asia. 14 (1): 5–25. doi:10.1163/22105018-990123777. ISSN 1464-8172. JSTOR 24572145 – via JSTOR.

- "Convention Between Great Britain and China Respecting Tibet (1906) [389]". www.tibetjustice.org. Archived from the original on 12 September 2009. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- Melvyn C. Goldstein. A History of Modern Tibet, 1913–1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State.

- Melvyn C. Goldstein. A History of Modern Tibet, 1913–1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State.

- McKay, Alex; McKay, Professor Alex (1997). Tibet and the British Raj: The Frontier Cadre, 1904–1947. Psychology Press. pp. xi. ISBN 978-0-7007-0627-3.

- Arpi, Claude (25 April 2014). "When India had a consulate general in Lhasa". Rediff. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- Atwill, David G. (2018), "The Tibetan Muslim Incident of 1960", Islamic Shangri-La, Inter-Asian Relations and Lhasa's Muslim Communities, 1600 to 1960 (1 ed.), University of California Press, pp. 92–122, ISBN 978-0-520-29973-3, JSTOR j.ctv941r61.9, retrieved 21 September 2020

- Samanta, Pranab Dhal (2 December 2006). "India wants consulate in Lhasa, Beijing says sorry". archive.indianexpress.com. Retrieved 21 September 2020.; Varma, K. J. M. (31 March 2015). "India to set up consulate in Chengdu as China says no to Lhasa". mint. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- Raman, B (8 August 2011). "A Consulate In Lhasa". Outlook India. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- Kunga Samten Dewatshang (1997). Flight at the Cuckoo's Behest, The Life and Times of a Tibetan Freedom Fighter. New Delhi: Paljor Publications. p. 149.; Gompo Tashi Andrugtsang (1973). Four Rivers, Six Ranges: Reminiscences of the Resistance Movement in Tibet. Dharamsala: Information and Publicity Office of H.H. The Dalai Lama. pp. 105–106.

- "60 Years Into Exile, Tibetans Say India Has Done A Lot For Them". Outlook India. 16 July 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "Central Tibetan Administration". Central Tibetan Administration. Archived from the original on 3 August 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- Ben Cahoon. "International Organizations N–W". Worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved 27 November 2011.; "UNPO: Tibet". unpo.org. 23 May 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- "127935 Tibetans living outside Tibet: Tibetan survey". Press Trust of India. 12 April 2010. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- Purohit, Kunal (21 March 2019). "After 60 years in India, why are Tibetans leaving?". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- Kalbag, Chaitanya (3 July 2019). "The Merry Monk and His Floundering Flock". Economic Times Blog. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- "60 years after fleeing Tibet, refugees in India get passports, not property". India Today. Reuters. 22 June 2017. Retrieved 24 September 2020.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Madhukar, Abhishek; Chandran, Rina (22 June 2017). "Sixty years after fleeing Tibet, refugees in India get passports, not property". Reuters. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- Purohit, Kunal (31 March 2018). "The search for home: Why Tibetans are leaving India". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- Madhukar, Abhishek (31 March 2018). "Dalai Lama calls on Tibetans to remain united as India drifts towards China". Reuters. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "Explained: What is the Special Frontier Force, referred to as Vikas Battalion?". The Indian Express. 2 September 2020. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- "Establishment-22 draws its strength from Karnataka". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- Mukhopadhyay, Ankita (14 September 2020). "India-China tension: Soldier's death puts spotlight on Tibetans in India | DW | 14.09.2020". DW. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- Shukla, Ajai (2 September 2020). "Ladakh intrusions: Special Frontier Force takes first casualties". Business Standard India. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- Mohan, Geeta (8 September 2020). "Ram Madhav attends Tibetan soldier's funeral, deletes tweet; experts debate if India has new Tibet policy". India Today. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- Van Eekelen, Willem Frederik (1967), Indian Foreign Policy and the Border Dispute with China, Springer, p. 19, ISBN 978-94-017-6555-8

- "'China Doesn't See Us as Friends': Patel's Letter to Nehru in 1950". TheQuint. 27 May 2020. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- Mehrotra 2000, p. 17.

- "Agreement on Trade and Intercourse with Tibet Region". www.mea.gov.in. 29 April 1954. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- Mehrotra 2000, p. 12.

- Mehrotra 2000, p. 25.

- Mehrotra 2000, p. 26.

- Mehrotra 2000, p. 27.

- Mehrotra 2000, p. 28, 46.

- Pai, Nitin (13 September 2020). "It is time India gave its policy on Tibet some strategic coherence". mint. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- Saran, Shyam (14 September 2020). "India waving SFF and Tibet cards won't scare China. Can't pull levers you don't have". ThePrint. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

Bibliography

- Mehrotra, LL (2000). India's Tibet Policy: An Appraisal and Options (PDF) (Third ed.). New Delhi: Tibetan Parliamentary and Policy Research Centre, New Delhi.

Further reading

- C. H. Alexandrowicz (April 1953). India and the Tibetan Tragedy. Foreign Affairs.

- Claude Arpi (2004). Cultural Relations between India and Tibet : An overview of the light from India. Dialogue. October–December 2004, Volume 6 No. 2.

- Arpi, Claude (2019). Tibet: When the Gods Spoke. India Tibet Relations (1947–1962), Part 3. New Delhi: Vij Books. ISBN 9789388161572.

- Arpi, Claude (2018). Will Tibet Ever Find Her Soul Again? India Tibet Relations (1947-1962), Part 2. New Delhi: Vij Books. ISBN 9788193759189.

- Arpi, Claude (2017). Tibet, the Last Months of a Free Nation: India Tibet Relations (1947-1962), Part 1. New Delhi: Vij Books. ISBN 9789386457226.