Transthoracic echocardiogram

A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) is the most common type of echocardiogram, which is a still or moving image of the internal parts of the heart using ultrasound. In this case, the probe (or ultrasonic transducer) is placed on the chest or abdomen of the subject to get various views of the heart. It is used as a non-invasive assessment of the overall health of the heart, including a patient's heart valves and degree of heart muscle contraction (an indicator of the ejection fraction). The images are displayed on a monitor for real-time viewing and then recorded.

| Transthoracic echocardiogram | |

|---|---|

| Purpose | still/moving image of internal parts of heart |

Details

A TTE is a clinical tool to evaluate the structure and function of the heart. All four chambers and all four valves can be assessed by TTE, but the quality and visibility of these structures varies from person to person. Other structures visible on TTE include the aorta, the pericardium, pleural effusions, ascites, and inferior vena cava. It can be used to detect a heart attack, enlargement/hypertrophy of the heart and infiltration of the heart from an abnormal substance (e.g. amyloidosis). Weakness of the heart, cardiac tumors and a variety of other findings can be diagnosed with a TTE. With advanced measurements of the movement of the tissue with time (Tissue Doppler), it can measure diastolic function, fluid status,[1] and ventricular dyssynchrony.

TTE in adults is also of limited use for the structures at the back of the heart, such as the left atrial appendage. Transesophageal echocardiography may be more accurate than TTE because it excludes the variables previously mentioned and allows closer visualization of common sites for vegetations and other abnormalities. Transesophageal Echocardiography also affords better visualization of prosthetic heart valves and clots within the four chambers of the heart. This type of Echocardiogram may be a better option for patients with thick chests, abnormal chest walls, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the obese.

"Bubble contrast TTE" involves the injection of agitated saline into a vein, followed by an Echocardiographic study. The bubbles are initially detected in the right atrium and right ventricle. If bubbles appear in the left heart, this may indicate a shunt, such as a patent foramen ovale, atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect or arteriovenous malformations in the lungs.[2]

If your doctor deems it necessary, a stress TTE may be performed. This can be accomplished by either exercising on a bike or treadmill, or by medicine given through an IV along with a contrast agent to make your bodily fluids show up brighter. This allows a comparison between your heart at rest and your heart when it is beating at a faster rate. (Transthoracic Echocardiogram, n.d.)

There are some risks associated when having an echocardiogram performed. It is possible that the images will not show up clearly enough, which can cause a misdiagnosis.

Indications

There are numerous indications for a TTE:

- Non-specific symptoms if cardiac etiology is suspected:

- Heart failure

- Heart murmur or known valve disease

- Chemotherapy (cardiotoxic)

- Chest pain for evaluation of wall motion abnormalities

- Congenital heart disease

- Endocarditis

- Hypoxemia for shunt evaluation

Examination

A typical TTE examination is done by either a cardiologist or a cardiac sonographer. It is a non-invasive test that can be done in many settings that include clinic exam room, inpatient rooms, and exam rooms dedicated to echo imaging. Examination involves using an echo probe at various windows to obtain views of the heart and capturing images/videos for later playback while formally "reading" the study to come up with findings of the study. Examination is usually done while laying flat and tilted onto the left side to bring the heart into better view. Ultrasound gel is used to improve the acoustic windows and increase quality of the captured images. Overall, an uncomplicated TTE exam takes less than 30 minutes.

Limited studies (ie, looking at only specific structures) can be done as a follow up exam to a full study, or can be done as "point of care" to answer specific questions in the appropriate setting. For example, critically ill patients often have "bedside ultrasounds" performed to assess particular questions the treating team has about their status. This could be looking for cardiac tamponade and acute valve regurgitation. Often, this may include examination of other organ systems such as lungs for effusions or the focused assessment with sonography for trauma.

Interpretation of the exam can be done by anyone trained in reading echocardiograms. However, this is often limited to cardiologists for "formal reading" of these studies. Anesthesiologists can perform intra-operative TEE's during surgical cases and they interpret their own studies. Anyone performing a bedside or "point of care" echocardiogram is expected to interpret their own study as it is performed. Pocket-sized TTE devices are growing in popularity.

Limitations

TTE is inherently limited in what it is capable of doing. Notably, it must be used through the skin, and ultrasound waves must go through skin and soft tissue before reaching the heart. This is in contrast to transesophageal echo (TEE) in which the probe is directly behind the left atrium in the esophagus and has far less tissue to penetrate, which means images from TEE are far superior in quality. Extremes in body sizes (obesity and cachexia) limit the acoustic windows and degrade the image quality of TTE's.

TTE is also limited in its views of structures. Being a surface modality, the structures closest to the skin are better visualized than those deeper to the skin. A common example that demonstrates this is the visibility of the left atrial appendage. This structure is known to form clots in atrial fibrillation and the LAA is rarely seen on TTE but readily seen on TEE. Cardioversion of atrial fibrillation in someone not on anticoagulation would require TEE to best visualize the LAA to rule out a thrombus. (If a thrombus is present, there is a much higher risk of stroke if returned to a sinus rhythm.)

Like all of the kinds of echocardiography, TTE is limited to structure and function. It is not, for example, able to determine perfusion of the myocardium, which would require a metabolic imaging modality such as PET or SPECT stress testing. Perfusion can be inferred based on wall motion, however.

Modalities

2D echo

This is the most common modality used today. A two-dimensional plane is formed by sweeping the ultrasound waves to obtain an image that varies with angle and depth. Evaluation of the structures is done in this view.

M-mode

This modality is obtained at a single angle and then plotted against time to obtain an image. It can be used to watch the movement of structures with time

Doppler

Color doppler

Color doppler is a form of 2D echo in which the doppler shift of the structures is shown as color. Typically, this is shown as red and blue with red indicating movement toward the transducer and blue indicating movement away from the transducer. This can be used to show blood flow through the valves to visually indicate the direction of blood flow. Abnormal blood flow can reflect stenosis and regurgitation of the valve. Color doppler can also show blood flow in abnormal locations such as with septal defects (ASD or VSD).

Color doppler can also be applied to M-mode. Using color doppler in this way gives better visualization of the changes in flow with time due to the higher frame rate with M-mode.

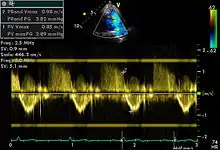

Spectral doppler

Spectral doppler is presented similarly to M-mode in which the doppler information is plotted as a spectrogram. This can be both "continuous" and "pulse" wave where the former shows the spectrum along a specific line and the latter shows within a small window along that line. Continuous wave is better at showing maximal velocities and pulse wave is better for showing flow through a small volume.

Spectral doppler is often used for quantification of flow. For example, the aortic valve area can be estimated using the continuity equation by measuring the velocity time integral (VTI) of the aortic valve & LV outflow tract; the VTI is calculated by tracing the flow on the spectral doppler curve. Spectral doppler is also useful for calculating the maximum flow and mean flow through a valve (used to grade valve stenosis).

Tissue doppler

Tissue doppler can be used to determine motion of myocardial tissue. This can be used to measure motion of the septal and lateral mitral annulus to suggest diastolic heart failure.

Axes

The images obtained with echocardiography are in reference to the heart itself. Two key axes of the heart are the long axis and short axis. The long axis is an imaginary line from the apex of the heart through the center of the mitral valve. The short axis is perpendicular to the long axis and shows the heart in cross section.

Windows

Evaluation of the heart with echocardiography requires having "acoustic windows" of the heart. Bone reflects the ultrasound waves and so all structures directly behind bone are not visible with ultrasound. This requires that the heart be viewed between bones and, in particular, between ribs. The most common views are the parasternal, apical, subcostal, and suprasternal windows..

- Parasternal: adjacent to the sternum. Without qualification, this means the left side of the heart but right parasternal views can be attempted.

- Apical: at the apex of the heart.

- Subcostal: below the sternum at the top of the abdomen

- Suprasternal: above the sternal at the base of the neck.

Views

There are several typical views obtained during a routine TTE. Views outside of the typical views can be considered "off axis" and may be obtained for specific purposes.

Parasternal long axis (PLAX)

This view is obtained to the left of the sternum and views the heart in its long axis. In this view, the mitral valve, aortic valve, right ventricular outflow tract, base of the left ventricle, and the left atrium can be visible. Angulation in this view can bring the right ventricular inflow tract and tricuspid valve into view, and angulation the opposite way can bring the pulmonary valve into view.

In this view, it is possible to appreciate the long-axis cross section of the mitral and aortic valves. The classic "hockey stick" shape of rheumatic mitral stenosis can be appreciated in this view. However, the angle of the probe with these valves can lead to under-appreciation of valve dysfunction.

The parasternal long view of the pulmonary valve is the only view of the posterior leaflet.

Structures visible:

- Anterior septal and inferior lateral walls of the left ventricle

- Left atrium

- Mitral valve in long-axis with chordae

- Aortic valve in long-axis

- Tricuspid valve in long-axis (angulated) and right ventricular inflow tract

- Pulmonary valve in long-axis (angulated) and right ventricular outflow tract

Measurements in this view can be used to quantify the heart:

- Left ventricular size and wall thickness

- Left atrial linear dimension (as opposed to area)

- Left ventricular outflow tract diameter (used to calculate aortic valve area by the continuity equation)

- Aortic annulus, sinus of Valsalva, and aortic root sizes

- Color doppler of all four valves

- Spectral doppler of tricuspid and pulmonary valves

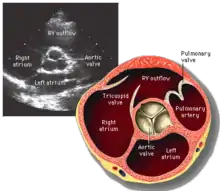

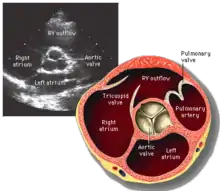

Parasternal short axis (PSAX)

This view is obtained in the same window as the parasternal long, but with the probe rotated 90°. In this view, the aortic valve is seen in cross-section with the right ventricular inflow & outflow tracts visible with the tricuspid valve as well. Pulmonary valve is not visible in this view. Both the right and left atria are visible.

The standard PSAX view is at the level of the aortic valve, but moving the probe along the long-axis can review the LV outflow tract, LV at the base, and LV at the midsection.

Structures visible:

- Aortic valve in short-axis

- Aortic valve dysfunction, aortic sclerosis/stenosis

- Tricuspid valve in long-axis

- Pulmonary valve in long-axis

- Right ventricle, including inflow and outflow tracts

- Left ventricle in short-axis

- Closer to the base can reveal the left ventricular outflow tract

- At the level of the base can show the movement of the mitral valve leaflets in short-axis

- At the level of mid-LV can show papillary muscles

Measurements in this view can be used to quantify the heart:

- Aortic valve area by planimetry

- Color doppler of all four valves

- Spectral doppler of tricuspid and pulmonary valves

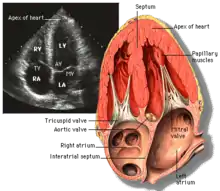

Apical four chamber (A4C)

This view is obtained at the apex of the heart and looking toward the base of the heart (where the valves are). In this view, the mitral valve, tricuspid valve, and all four chambers are visible. This view shows the right ventricle from base to apex and is a useful view to estimate RV systolic function. TAPSE (= tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion) is also measured in this view with M-mode through the lateral tricuspid annulus.

Structures:

- Inferior septum and anterior lateral segments of the left ventricle

- Right ventricle

- Left atrium

- Right atrium

- Mitral valve

- Tricuspid valve

Measurements in this view can be used to quantify the heart:

- RV size and function; TAPSE

- Left atrial size

- Right atrial size

- Mitral valve flow is best seen in this view and has the best angle with probe to estimate flows

- Tricuspid valve flow

- Tissue doppler at the mitral valve annulus (septum and lateral wall) for diastolic function

- Agitated saline bubble study for right to left shunting (PFO, ASD, VSD)

- With contrast, apical and mural LV thrombi can be easily seen

Apical three chamber (A3C)

This view is obtained at the same window as the apical four chamber and then rotation of the probe. In this view, the mitral valve and aortic valve are in view and is roughly similar to the parasternal long axis. In this view, the LV outflow tract is best in alignment with the probe and so gives the best estimate of flow through the LVOT, which is commonly used to estimate aortic stenosis.

Structures:

- Aortic valve

- Mitral valve

- Left ventricle

- Left atrium

Measurements in this view can be used to quantify the heart:

- Left ventricular outflow tract volume-time integral (LVOT VTI) to be used in conjunction with aortic valve VTI for aortic valve area and stenosis

- Mitral valve flow

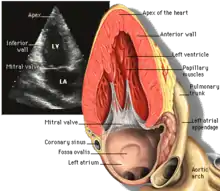

Apical two chamber (A2C)

This view is obtained at the same window as the apical four chamber and then rotation of the probe. In this view, the mitral valve is visible with the left atrium and left ventricle.

Structures:

- Anterior and inferior segments of the left ventricle

- Mitral valve in long-axis

- Left atrium

Measurements in this view can be used to quantify the heart:

- Mitral valve flow

- Spectral doppler of the mitral valve

Subcostal

This view is obtained below the sternum and at the top part of the abdomen. In this view, the junction of the inferior vena cava with the right atrium is best seen. From this window, it is possible in some people to see roughly equivalent views of the apical four chamber and parasternal short views. In some people, this may afford these common views but at a subcostal window that may not be obtained through the parasternal and/or apical windows because of various reasons such as chest wall trauma, open wounds, or poor acoustic windows. However, the subcostal window is the only window to view the inferior vena cava that can help support an estimation of the central venous pressure based on size and collapsibility during respiration.

Other non-cardiac structures are visible in this view and some pathologies — such as ascites — can be observed.

Suprasternal (SSN)

This view is obtained above the sternum in the suprasternal notch. In this view, the aortic arch and portion of the descending aorta can be seen. Color and spectral doppler through the descending aorta can show signs of coarctation of the aorta.

Structures

Examples of TTE views of various structures of the heart.

Aortic valve

PSAX

PSAX

Measurements

.svg.png.webp)

Routine TTE exams can provide a significant wealth of information about the heart's structure and function:

- Left ventricular size, thickness, systolic function, and diastolic function

- Right ventricular size and systolic function

- Aortic valve

- Aortic valve sclerosis & stenosis

- Aortic valve insufficiency

- Mitral valve

- Mitral stenosis

- Mitral regurgitation

- Tricuspid valve

- Tricuspid regurgitation (stenosis is possible, but rare)

- Pulmonary valve

- Pulmonary regurgitation (stenosis is possible, but rare)

- Inferior vena cava size as estimate of central venous pressure

- Aortic root size for thoracic ascending aortic aneurysm

- Pericardial effusion size

All function dysfunction is graded on a scale (normal, trace, mild, moderate, or severe) based on various criteria. Grading of valve function is used for prognosis and helps determine management as valve dysfunction progresses.

Echo societies have published normal ranges for various features of the heart on various views to promote TTE as a quantifiable assessment of the heart.

Equations

Quantitative echo utilizes a number of equations to calculate aspects of the heart structure and function. Simplified Bernoulli equation and continuity equation are two common equations used. Others are used in grading valve function (e.g., EROA, PISA).

Diseases

TTE can be useful for diagnosing many cardiac diseases.

- Cardiomyopathy: dilated, restrictive, and hypertrophic

- Pulmonary hypertension (requires some degree of tricuspid regurgitation)

- Septal defects including ASD & VSD

- Stenosis and regurgitation/insufficiency of valves

- Structure and function of prosthetic valves

- Thoracic ascending aortic aneurysm

- Infiltrative diseases such as amyloidosis

- Cardiac tamponade (although a clinical diagnosis, it can suggest subclinical diagnosis)

- Evaluation of congenital diseases (e.g., Tetralogy of Fallot, transposition)

- Pulmonary embolism

- Endocarditis (sensitivity is higher with TEE)

Notes

- Ommen SR, Nishimura RA, Appleton CP, Miller FA, Oh JK, Redfield MM, Tajik AJ (2000). "Clinical utility of Doppler echocardiography and tissue Doppler imaging in the estimation of left ventricular filling pressures: A comparative simultaneous Doppler-catheterization study" (PDF). Circulation. 102 (15): 1788–94. doi:10.1161/01.cir.102.15.1788. PMID 11023933.

- Soliman OI, Geleijnse ML, Meijboom FJ, Nemes A, Kamp O, Nihoyannopoulos P, Masani N, Feinstein SB, Ten Cate FJ (June 2007). "The use of contrast echocardiography for the detection of cardiac shunts". European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Imaging. 8 (3): s2–s12. doi:10.1016/j.euje.2007.03.006. PMID 17462958. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

External links

- Echocardiography online free education platform (TECHmED)

- Virtual Transthoracic Echocardiography - online learning resource

- Basic ultrasound, echocardiography and Doppler for clinicians

- https://www.drugs.com/cg/transthoracic-echocardiogram.html

- [Transthoracic Echocardiogram - What You Need to Know. (n.d.). Retrieved December 10, 2017, from https://www.drugs.com/cg/transthoracic-echocardiogram.html]