Tredegar Iron Works

The Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, Virginia, was the biggest ironworks in the Confederacy during the American Civil War, and a significant factor in the decision to make Richmond its capital.

Tredegar Iron Works | |

.jpg.webp) Tredegar Iron Works, Richmond, Virginia, U.S., photograph by Alexander Gardner | |

| |

| Location | Richmond, Virginia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°32′8″N 77°26′43″W |

| Built | 1841 |

| Architect | Reev Davis |

| NRHP reference No. | 71001048[1] |

| VLR No. | 127-0186 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | July 2, 1971 |

| Designated NHLD | December 22, 1977[2] |

| Designated VLR | January 5, 1971[3] |

Tredegar supplied about half the artillery used by the Confederate States Army, as well as the iron plating for CSS Virginia, the first Confederate ironclad warship, which fought in the historic Battle of Hampton Roads in March 1862. The works avoided destruction by troops during the evacuation of the city, and continued production through the mid-20th century. Now classified as a National Historic Landmark District, the site serves as the main building of the American Civil War Museum.

The name Tredegar derives from the Welsh industrial town that supplied much of the company's early workforce.

History

Founding (1836–1841)

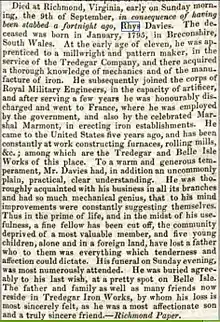

In 1836, a group of Richmond businessmen and industrialists led by Francis B. Deane, Jr. set about to capitalize on the growing railroad boom in the United States.[4] The group hired Rhys Davies, then a young engineer, to construct a new facility, brought a number of his fellow iron workers from Tredegar, Wales, to construct the furnaces and rolling mills. The foundry was named in honor of the town of Tredegar, where iron works of the same name were constructed in the early 19th century. The new works opened in 1837, yet the Panic of 1837 and accompanying downturn resulted in hardship for the new company.[4] Davies died in Richmond in September 1838 from stab wounds sustained in a fight with a workman and was buried on Belle Isle in the James River.

Management under Joseph Reid Anderson (1841 – Civil War)

In 1841, the owners turned management over to a 28-year-old civil engineer named Joseph Reid Anderson who proved to be an able manager. Anderson acquired ownership of the foundry in 1848, after two years of leasing the works, and was soon doing work for the United States government.[4] Anderson began introducing slave labor to cut production costs. By the beginning of the Civil War in 1861, half of the 900 workers were slaves, including many in skilled positions.[5] By 1860, Anderson's father-in-law Dr. Robert Archer had joined the business and Tredegar became a leading iron producer in the country.

The commissioning of 900 miles of railroad track in Virginia, largely financed by the Virginia Board of Public Works between 1846 and 1853, offered a further market in steam locomotives and rail stock. One of those attributed with starting the Tredegar Locomotive Works with John Souther was Zerah Colburn, the well-known locomotive engineer and journalist. The company produced about 70 steam locomotives between 1850 and 1860. From 1852 to 1854, John Souther also managed the locomotive shop at Tredegar. Its locomotive production work is sometimes listed with combinations of the names Anderson, Souther, Delaney, and Pickering. Tredegar also produced the steam propulsion plants for the USS Roanoke (1855) and the USS Colorado (1856).[6]

Prior to the Civil War, industry expanded at the Tredegar site under Anderson's direction to include a new flour mill on land leased to Lewis D. Crenshaw and a stove works on land leased to A.J. Bowers and Asa Snyder.[7] By 1860, Crenshaw and Co. had established the Crenshaw Woolen Mill on adjoining land they owned. This enterprise employed more than 50 people.[8] The Crenshaw Woolen Mill became "the principal source of supply for the [Confederate] Army's requirements of uniform material" during the first half of the Civil War.[9] A May 16, 1863 fire on the Tredegar/Crenshaw site damaged the mill, which was not rebuilt, and Tredegar purchased the land from Crenshaw and Co. by 1863.[10][11][12]

American Civil War

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

By 1860, the Tredegar Iron Works was the largest of its kind in the South, a fact that played a significant role in the decision to relocate the capital of the Confederacy from Montgomery, Alabama, to Richmond in May 1861.[13] Tredegar supplied high-quality munitions to the Confederacy during the war.

Its wartime production included the iron plating for the first Confederate ironclad warship, the CSS Virginia which fought in the historic Battle of Hampton Roads in March 1862; credit for approximately 1,100 artillery pieces during the war, about half of the South's total domestic production of artillery during the war years of 1861–1865, including the development of the Brooke rifle;[4] a giant rail-mounted siege cannon. The company also manufactured railroad steam locomotives in the same period.

As a result of his difficulties competing with Northern industries due to his higher labor and raw material costs,[4] Anderson was a strong supporter of southern secession and became a Brigadier General in the Confederate Army as the war broke out. He was wounded at Glendale during the Seven Days Battles of the Peninsula Campaign in 1862 and served in the Ordnance Department for the duration of the Civil War.

As the war continued with more and more men conscripted into the Confederate armies, Tredegar experienced a lack of skilled laborers. Scarce supplies of metal also hurt the company's manufacturing abilities during the war and as the conflict progressed it was noticed that Tredegar's products were beginning to lose quality as well as quantity. Even in the summer of 1861, soon after the beginning of the Civil War, metal was so scarce that the iron works failed to produce a single piece of artillery for an entire month.

During the evacuation of Richmond by the Confederates on the night of April 2–3, 1865, the retreating troops were under orders to burn munitions dumps and industrial warehouses that would have been valuable to the North. Anderson reportedly paid over 50 armed guards to protect the facility from arsonists. As a result, the Tredegar Iron Works is one of few Civil War-era buildings that survived the burning of Richmond.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |||||||||||||||||

| Tredegar Ironworks and associated facilities, as it appeared shortly after the fall of Richmond in 1865 (Present-day surviving structures italicized)[14]

| |||||||||||||||||

After the Civil War

At the outset of hostilities, Anderson had wisely secured Tredegar assets overseas for the duration of the Civil War and, therefore, was able to restore his business when the Confederate currency collapsed. He petitioned U.S. President Andrew Johnson for a pardon for himself and Tredegar and was back in business before the end of 1865, regaining full ownership in 1867. That same year, Tredegar incorporated with a stock of $1,000,000.[6]

Francis Thomas Glasgow, the father of Virginia writer and suffragist Ellen Glasgow, was a manager at Tredegar Iron Works, and Joseph Reid Anderson was her maternal uncle.[15][16][17]

By 1873, Tredegar Iron Works was employing 1,200 workers and was a profitable business. However, the Panic of 1873 hit the company hard, and as a result of financing difficulties it did not transition to steel, and so faded from national prominence.[4]

The neighborhood of Oregon Hill cropped up as a company town-like development. When Joseph Anderson died on a vacation in New Hampshire in 1892, he was succeeded by his son Colonel Archer Anderson. The Tredegar company remained in business throughout the first half of the 20th century, and supplied requirements of the armed forces of the United States during World War I and World War II. In 1957, Anderson's descendants sold the land to Ethyl Corporation, who began restoration of some of the surviving structures.[4]

Preservation as a Civil War museum site and tourist attraction

In the 21st century, the buildings at the Tredegar site have been preserved through development of the site to commemorate the Civil War. The site is also used for various festivals and public events such as the Richmond Folk Festival.

The Pattern Building is used as the main visitors' center for Richmond National Battlefield Park. The American Civil War Center at Historic Tredegar is a separate museum at the former Tredegar Ironworks.

Valentine Riverside

In the 1990s, the Court End-based Valentine Museum opened a second museum site at the Tredegar Ironworks. The focus of the museum experience was industrial history. Interpretive tours to and from the site covered industrial history, African American history, and Civil War history. The venture, however, was short-lived. The "Valentine on the James" opened on Memorial Day 1994 and closed to the public on Labor Day 1995.

Civil War Visitor Center at Tredegar Iron Works

The main visitor center for Richmond National Battlefield Park opened at the Tredegar Iron Works site in June 2000. The Civil War Visitor Center at Tredegar Iron Works is located in the restored pattern building and offers three floors of exhibits, an interactive map table, a film about the Civil War battles around Richmond, a bookstore, and interpretive NPS rangers on site daily to provide programs and to aid visitors.

Lincoln statue

In 2000, the former Tredegar Iron Works facility overlooking the James River near downtown Richmond became the site of the main Visitor's Center of the Richmond National Battlefield Park. Sculptor David Frech of Newburgh, New York, was commissioned by The United States Historical Society of Richmond to commemorate the historic arrival of Abraham Lincoln and his son Tad Lincoln and their tour of the burnt-out Union-captured Richmond, Virginia, April 4, 1865, 10 days before his assassination.

Funds were raised by the Historical society through donations and the selling of miniature versions of the statue as well as bronzed resin copies.[18] The statue, much like the Arthur Ashe Monument, received a wide array of criticism for its placement. Traditionally reserved for statues of key figures of the Confederacy protests were held at the unveiling April 5, 2003, namely by the Sons of Confederate Veterans. Robert H. Kline, chairman of the historical society, the Richmond-based nonprofit company that commissioned the statue stated that the statue was for the purpose of reconciliation "He came on a mission of peace and reconciliation and I think the statue will serve that purpose for a very long time"[19]

Opponents of the statue claim that the statue commemorates Lincoln's arrival into Richmond a proud victor. Bragdon Bowling, Virginia division commander of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, was among the speakers protesting the statues unveiling stating that it represented "a slap in the face of a lot of brave men and women who went through four years of unbelievable hell fighting an invasion of Virginia led by President Lincoln."[18] and that "As a Southerner, I'm offended. You wouldn't put a statue of Winston Churchill in downtown Berlin, would you? What's next, a statue of Sherman in Atlanta?".[19] Other notable protesters include Fred Taylor, president of the Heritage Preservation Association; and Elliott Germain, chairman Virginia League of the South.

Dignitaries at the installation ceremony included former governors Douglas Wilder and Gerald L. Baliles, former Mayor of Richmond, then-Lt. Governor, and future Governor Tim Kaine, and then-Mayor of Richmond Rudy McCollum. The dedication ceremony was buzzed by a plane trailing a banner proclaiming Sic semper tyrannis, which is not only Virginia's motto (meaning "Thus always to tyrants"), but also what John Wilkes Booth, according to his diary, called out while assassinating Lincoln.[20]

The statue is made of a bronze cast depicting Lincoln and his son Tad on a bench with Lincoln's arm around his son. The bench was deliberately made long enough so that viewers may sit next to either statue on the bench to take photographs. The words "To Bind Up The Nation's Wounds" from Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address are carved into granite behind them.[21]

American Civil War Center at Historic Tredegar

The idea of another museum on the site was later realized on Saturday, October 7, 2006, The American Civil War Center at Historic Tredegar opened to the public. James M. McPherson described the museum as "a truly comprehensive exhibit and education center weaving together Union, Confederate, and African-American threads ... much needed for future generations to understand how the Civil War shaped the nation." The Center contains interactive theaters, plasma-screen maps, and artifacts. The museum's exhibits were put together by a team of historians that included James M. McPherson of Princeton, Bill Cooper of Louisiana State University, John Fleming of the Cincinnati Museum Center, Charles Dew of Williams College, David W. Blight of Yale and Emory Thomas at the University of Georgia. In November 2013 the Civil War Center was merged with the Museum of the Confederacy[22] and became the American Civil War Museum in January 2014.[23]

In Harry Turtledove's Southern Victory Series of alternate history novels, in which the South wins the Civil War, the Confederate Army's standard rifle is called the Tredegar, produced by what is by then called the Tredegar Steel Works.

See also

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- "Tredegar Iron Works". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2009-01-14. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- "Tredegar Iron Works National Historic Landmark nomination" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- Bumgardner, Sarah (November 29, 1995). "Tredegar Iron Works: A Synecdoche for Industrialized Antebellum Richmond". Antebellum Richmond. Archived from the original on September 8, 2008.

- Wood, James P. (1886). The Industries of Richmond: Her Trade, Commerce, Manufactures and Representative Establishments. Richmond, Virginia: The Metropolitan Publishing Co. pp. 53–54.

- "A Guide to the Tredegar Iron Works Records, 1801-1957"

- The Richmond Dispatch, October 31, 1860, p. 1, c. 6.

- "Captain William G[raves] Crenshaw, C.S.A., The War Years," William G. Crenshaw III, Virginia State Library, Richmond, VA, Archives #25261.

- Richmond Dispatch, Saturday Morning, May 16, 1863 Archived April 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, p. 1.

- "Richmond Examiner, 7/4/1863". Mdgorman.com. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- The Richmond Sentinel, December 17, 1863, p. 1, c. 2.

- "Richmond During the Civil War". Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- Dew, Charles B. (1999). Ironmaker to the Confederacy (2nd ed.). Library of Virginia.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-02-06. Retrieved 2017-02-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Summary of The Voice of the People". Docsouth.unc.edu. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- "Summary of The Battle-Ground". Docsouth.unc.edu. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- Lincoln Statue To Be Put Up In Richmond Archived 2011-06-14 at the Wayback Machine

- "Lincoln Statue Is Unveiled, And Protesters Come Out". The New York Times. April 6, 2003.

- Rothstein, Edward (September 2, 2008). "Away Down South, 2 Museums Grapple With the Civil War Story". New York Times. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- . 20 July 2011 https://web.archive.org/web/20110720120318/http://niahd.wm.edu/attachments/8475.jpg. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 3 October 2018. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Calos, Katherine (November 17, 2013). "Civil War center, Confederacy museum join forces". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- Boyd, Scott C. (February–March 2014). "'American Civil War Museum' Is The Name For Richmond Civil War Entity". Civil War News. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tredegar Iron Works. |

- The American Civil War Center at Historic Tredegar

- Teachinghistory.org Review of American Civil War Center: Educational Web Companion

- National Park Service, Richmond National Battlefield Park

- National Park Service, Introduction to Tredegar Iron Works

- Richmond Enquirer newspaper article (28 September 1861) about the foundry

- Detailed history of the foundry by B. Gardner

- Confederate Railroads website

- Photos

- Tredegar Iron Works: Rebuilding Yankee/Rebel History Commonwealth Times April 4, 1978

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. VA-32, "Tredegar Iron Works, U.S. Route 1, along James River, Richmond, Independent City, VA", 5 photos, 6 data pages, 1 photo caption page