Turkish phonology

The phonology of Turkish is the pronunciation of the Turkish language. It deals with current phonology and phonetics, particularly of Istanbul Turkish. A notable feature of the phonology of Turkish is a system of vowel harmony that causes vowels in most words to be either front or back and either rounded or unrounded. Velar stop consonants have palatal allophones before front vowels.

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | |||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | t͡ʃ | (c)1 | k4 | |

| voiced | b | d | d͡ʒ | (ɟ)1 | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | f3 | s | ʃ | h | ||

| voiced | v | z | ʒ3 | ||||

| Approximant | (ɫ)1 | l | j | (ɰ)2 | |||

| Flap | ɾ | ||||||

- In native Turkic words, the velar consonants /k, ɡ/ are palatalized to [c, ɟ] (similar to Russian) when adjacent to the front vowels /e, i, ø, y/. Similarly, the consonant /l/ is realized as a clear or light [l] next to front vowels (including word finally), and as a velarized [ɫ] next to the central and back vowels /a, ɯ, o, u/. These alternations are not indicated orthographically: the same letters ⟨k⟩, ⟨g⟩, and ⟨l⟩ are used for both pronunciations. In foreign borrowings and proper nouns, however, these distinct realizations of /k, ɡ, l/ are contrastive. In particular, [c, ɟ] and clear [l] are sometimes found in conjunction with the vowels [a] and [u]. This pronunciation can be indicated by adding a circumflex accent over the vowel: e.g. gâvur ('infidel'), mahkûm ('condemned'), lâzım ('necessary'), although the use of this diacritic has become increasingly archaic.[2] An example of a minimal pair is kar ('snow') vs. kâr (with palatalized [c]) ('profit').[3]

- In addition, there is a debatable phoneme, called yumuşak g ('soft g') and written ⟨ğ⟩, which only occurs after a vowel. It is sometimes transcribed /ɰ/ or /ɣ/. Between back vowels, it may be silent or sound like a bilabial glide. Between front vowels, it is either silent or realized as [j], depending on the preceding and following vowels. When not between vowels (that is, word finally and before a consonant), it is generally realized as vowel length, lengthening the preceding vowel, or as a slight [j] if preceded by a front vowel.[4] According to Zimmer & Orgun (1999), who transcribe this sound as /ɣ/:

- Word-finally and preconsonantally, it lengthens the preceding vowel.[3]

- Between front vowels it is an approximant, either front-velar [ɰ̟] or palatal [j].[3]

- Otherwise, intervocalic /ɣ/ is phonetically zero (deleted).[3] Before the loss of this sound, Turkish did not allow vowel sequences in native words, and today the letter ⟨ğ⟩ serves largely to indicate vowel length and vowel sequences where /ɰ/ once occurred.[5]

- The phonemes /ʒ/ and /f/ only occur in loanwords and interjections.

- [q] is an allophone of /k/ before back vowels /a, ɯ, o, u/ in many dialects in eastern and southeastern Turkey, including Hatay dialect.

Phonetic notes:

- /m, p, b/ are bilabial, whereas /f, v/ vary between bilabial and labiodental.[6][7]

- Some speakers realize /f/ as bilabial [ɸ] when it occurs before the rounded vowels /y, u, ø, o/ as well as (although to a lesser extent) word-finally after those rounded vowels. In other environments, it is labiodental [f].[7]

- The main allophone of /v/ is a voiced labiodental fricative [v]. Between two vowels (with at least one of them, usually the following one, being rounded), it is realized as a voiced bilabial approximant [β̞], whereas before or after a rounded vowel (but not between vowels), it is realized as a voiced bilabial fricative [β]. Some speakers have only one bilabial allophone.[7]

- /n, t, d, s, z/ are dental [n̪, t̪, d̪, s̪, z̪], /ɫ/ is velarized dental [ɫ̪], /ɾ/ is alveolar [ɾ], whereas /l/ is palatalized post-alveolar [l̠ʲ].[1][8]

- /ɾ/ is frequently devoiced word-finally and before a voiceless consonant.[3] According to one source,[9] it is only realized as a modal tap intervocalically. Word-initially, a location /ɾ/ is restricted from occurring in native words, the constriction at the alveolar ridge narrows sufficiently to create frication but without making full contact, [ɾ̞]; the same happens in word-final position: [ɾ̞̊].[9]

- /ɫ/ and /l/ are often also voiceless in the same environments (word-final and before voiceless consonants).[3]

- Syllable-initial /p, t, c, k/ are usually aspirated.[3]

- /t͡ʃ, d͡ʒ/ are affricates, not plosives. They have nevertheless been placed in the table in that manner (patterning with plosives) in order to both save space and reflect the phonology better.

- Final /h/ may be fronted to a voiceless velar fricative [x].[3] It may be fronted even further after front vowels, then tending towards a voiceless palatal fricative [ç].

- /b, d, d͡ʒ, ɡ, ɟ/ are devoiced to [p, t, t͡ʃ, k, c] word- and morpheme-finally, as well as before a consonant: /edˈmeɟ/ ('to do, to make') is pronounced [etˈmec]. (This is reflected in the orthography, so that it is spelled ⟨etmek⟩). When a vowel is added to nouns ending with postvocalic /ɡ/, it is lenited to ⟨ğ⟩ (see below); this is also reflected in the orthography.[note 1]

Consonant assimilation

Because of assimilation, an initial voiced consonant of a suffix is devoiced when the word it is attached to ends in a voiceless consonant. For example,

- the locative of şev (slope) is şevde (on the slope), but şef (chef) has locative şefte;

- the diminutive of ad (name) is adcık [adˈd͡ʒɯk] ('little name'), but at ('horse') has diminutive atçık [atˈt͡ʃɯk] ('little horse').

Phonotactics

Turkish phonotactics is almost completely regular. The maximal syllable structure is (C)V(C)(C).[note 2] Although Turkish words can take multiple final consonants, the possibilities are limited. Multi-syllable words are syllabified to have C.CV or V.CV syllable splits, C.V split is disallowed, V.V split is only found in rare specific occurrences.

Turkish only allows complex onsets in a few recent English, French and Italian loanwords, making them CCVC(C)(C), such as Fransa, plan, program, propaganda, strateji, stres, steril and tren. Even in these words, the complex onsets are only pronounced as such in very careful speech. Otherwise, speakers often epenthesize a vowel after the first consonant. Although some loanwords add a written vowel in front of them to reflect this breaking of complex onsets (for example the French station was borrowed as istasyon to Turkish), epenthetic vowels in loan words are not usually reflected in spelling. This differs from orthographic conventions of the early 20th century that did reflect this epenthesis.

- All syllables have a nucleus

- No diphthongs in the standard dialect (/j/ is always treated as a consonant)

- No word-initial /ɰ/ or /ɾ/ (in native words)

- No long vowel followed by syllable-final voiced consonant (this essentially forbids trimoraic syllables)

- No complex onsets (except for the exceptions above)

- No /b, d͡ʒ, d, ɟ, ɡ/ in coda (see Final-obstruent devoicing), except for some recent loanwords such as psikolog and five contrasting single-syllable words: ad "name" vs. at "horse", hac "Hajj" vs. haç "holy cross", İd (city name) vs. it "dog", kod "code" vs. kot "jeans", od "fire" vs. ot "grass".

- In a complex coda:

- The first consonant is either a voiceless fricative, /ɾ/ or /l/

- The second consonant is either a voiceless plosive, /f/, /s/, or /h/

- Two adjacent plosives and fricatives must share voicing, even when not in the same syllable, but /h/ and /f/ are exempt

- No word-initial geminates - in all other syllables, geminates are allowed only in the onset (hyphenation and syllabification in Turkish match except for this point; hyphenation splits the geminates)

Rural dialects regularize many of the exceptions said above.

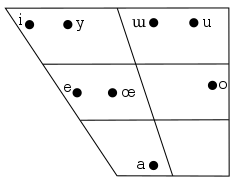

Vowels

The vowels of the Turkish language are, in their alphabetical order, ⟨a⟩, ⟨e⟩, ⟨ı⟩, ⟨i⟩, ⟨o⟩, ⟨ö⟩, ⟨u⟩, ⟨ü⟩. There are no phonemic diphthongs in Turkish and when two vowels are adjacent in the spelling of a word, which only occurs in some loanwords, each vowel retains its individual sound (e.g. aile [a.i.le], laik [la.ic]). In some words, a diphthong in the donor language (e.g. the [aw] in Arabic نَوْبَة [naw.ba(t)]) is replaced by a monophthong (for the example, the [œ] in nöbet [nœ.bet]). In some other words, the diphthong becomes a two-syllable form with a semivocalic /j/ in between.

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | unrounded | rounded | |

| Close | i | y | ɯ | u |

| Open | e | œ | a | o |

- /ɯ/ has been variously described as close back [ɯ],[11] near-close near-back [ɯ̽][12] and close central [ɨ] with a near-close allophone ([ɨ̞]) that occurs in the final open syllable of a phrase.[3]

- /e, o, œ/ are phonetically mid [e̞, o̞, ø̞].[3][13][12] For simplicity, this article omits the relative diacritic even in phonetic transcription.

- /e/ corresponds to /e/ and /æ/ in other Turkic languages. Sound merger started in the 11th century and finished in early Ottoman era.[14] Most speakers lower /e/ to [ɛ]~[æ] before coda /m, n, l, r/, so that perende 'somersault' is pronounced [perɛnˈde]. There are a limited number of words, such as kendi 'self' and hem 'both', which are pronounced with [æ] by some people and with [e] by some others.[11]

- /a/ has been variously described as central [ä][3] and back [ɑ],[11] because of the vowel harmony. For simplicity, this article uses the diacriticless symbol ⟨a⟩, even in phonetic transcription. /a/ is phonologically a back vowel, because it patterns with other back vowels in harmonic processes and the alternation of adjacent consonants (see above). The vowel /e/ plays the role as the "front" analog of /a/.

- /i, y, u, e, ø/ (but not /o, a/) are lowered to [ɪ, ʏ, ʊ, ɛ, œ] in environments variously described as "final open syllable of a phrase"[3] and "word-final".[13]

| Phoneme | IPA | Orthography | English translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| /i/ | /ˈdil/ | dil | 'tongue' |

| /y/ | /ɟyˈneʃ/ | güneş | 'sun' |

| /ɯ/ | /ɯˈɫɯk/ | ılık | 'warm' |

| /u/ | /uˈtʃak/ | uçak | 'aeroplane' |

| /e/ | /ˈses/ | ses | 'sound' |

| /œ/ | /ˈɟœz/ | göz | 'eye' |

| /o/ | /ˈjoɫ/ | yol | 'way' |

| /a/ | /ˈdaɫ/ | dal | 'branch' |

Vowel harmony

| Turkish Vowel Harmony | Front | Back | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | Unrounded | Rounded | |||||

| Vowels | e /e/ | i /i/ | ü /y/ | ö /œ/ | a /a/ | ı /ɯ/ | u /u/ | o /o/ |

| Twofold (Simple system) | e | a | ||||||

| Fourfold (Complex system) | i | ü | ı | u | ||||

With some exceptions, native Turkish words follow a system of vowel harmony, meaning that they incorporate either exclusively back vowels (/a, ɯ, o, u/) or exclusively front vowels (/e, i, œ, y/), as, for example, in the words karanlıktaydılar ('they were in the dark') and düşünceliliklerinden ('due to their thoughtfulness'). /o ø/ only occur in the initial syllable.

The Turkish vowel system can be considered as being three-dimensional, where vowels are characterised by three features: front/back, rounded/unrounded, and high/low, resulting in eight possible combinations, each corresponding to one Turkish vowel, as shown in the table.

Vowel harmony of grammatical suffixes is realized through "a chameleon-like quality",[15] meaning that the vowels of suffixes change to harmonize with the vowel of the preceding syllable. According to the changeable vowel, there are two patterns:

- twofold (/e/~/a/):[note 3] Backness is preserved, that is, /e/ appears following a front vowel and /a/ appears following a back vowel. For example, the locative suffix is -de after front vowels and -da after back vowels. The notation -de2 is shorthand for this pattern.

- fourfold (/i/~/y/~/ɯ/~/u/): Both backness and rounding are preserved. For example, the genitive suffix is -in after unrounded front vowels, -ün after rounded front vowels, -ın after unrounded back vowels, and -un after rounded back vowels. The notation -in4 can be this pattern's shorthand.

The vowel /ø/ does not occur in grammatical suffixes. In the isolated case of /o/ in the verbal progressive suffix -i4yor it is immutable, breaking the vowel harmony such as in yürüyor ('[he/she/it] is walking'). -iyor stuck because it derived from a former compounding "-i yorı".[note 4]

Some examples illustrating the use of vowel harmony in Turkish with the copula -dir4 ('[he/she/it] is'):

- Türkiye'dir ('it is Turkey') – with an apostrophe because Türkiye is a proper noun.

- gündür ('it is the day')

- kapıdır ('it is the door')

- paltodur ('it is the coat').

Compound words do not undergo vowel harmony in their constituent words as in bugün ('today'; from bu, 'this', and gün, 'day') and başkent ('capital'; from baş, 'prime', and kent, 'city') unless it is specifically derived that way. Vowel harmony does not usually apply to loanword roots and some invariant suffixes, such as and -ken ('while ...-ing'). In the suffix -e2bil ('may' or 'can'), only the first vowel undergoes vowel harmony. The suffix -ki ('belonging to ...') is mostly invariant, except in the words bugünkü ('today's') and dünkü ('yesterday's').

There are a few native Turkish words that do not have vowel harmony such as anne ('mother'). In such words, suffixes harmonize with the final vowel as in annedir ('she is a mother'). Also suffixes added to foreign borrowings and proper nouns usually harmonize their vowel with the syllable immediately preceding the suffix: Amsterdam'da ('in Amsterdam'), Paris'te ('in Paris').

Consonantal effects

In most words, consonants are neutral or transparent and have no effect on vowel harmony. In borrowed vocabulary, however, back vowel harmony can be interrupted by the presence of a "front" (i.e. coronal or labial) consonant, and in rarer cases, front vowel harmony can be reversed by the presence of a "back" consonant.

| noun | dative case | meaning | type of l | noun | dative case | meaning | type of l |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hâl | hâle | situation | clear | rol | role | role | clear |

| hal | hale | closed market | clear | sol | sole | G (musical note) | clear |

| sal | sala | raft | dark | sol | sola | left | dark |

For example, Arabic and French loanwords containing back vowels may nevertheless end in a clear [l] instead of a velarized [ɫ]. Harmonizing suffixes added to such words contain front vowels.[16] The table above gives some examples.

Arabic loanwords ending in ⟨k⟩ usually take front-vowel suffixes if the origin is kāf, but back-vowel suffixes if the origin is qāf: e.g. idrak-i ('perception' acc. from إدراك idrāk) vs. fevk-ı ('top' acc. from ← فوق fawq). Loanwords ending in ⟨at⟩ derived from Arabic tāʼ marbūṭah take front-vowel suffixes: e.g. saat-e ('hour' dat. from ساعة sāʿat), seyahat-e ('trip' dat. from سياحة siyāḥat). Words ending in ⟨at⟩ derived from the Arabic feminine plural ending -āt or from devoicing of Arabic dāl take the expected back-vowel suffixes: e.g. edebiyat-ı ('literature' acc. from أدبيّات adabiyyāt), maksat, maksadı ('purpose', nom. and acc. from مقصد maqṣad).[17]

Front-vowel suffixes are also used with many Arabic monosyllables containing ⟨a⟩ followed by two consonants, the second of which is a front consonant: e.g. harfi ('letter' acc.), harp/harbi ('war', nom. and acc.). Some combinations of consonants give rise to vowel insertion, and in these cases the epenthetic vowel may also be front vowel: e.g. vakit ('time') and vakti ('time' acc.) from وقت waqt; fikir ('idea') and fikri (acc.) from فِكْر fikr.[18]

There is a tendency to eliminate these exceptional consonantal effects and to apply vowel harmony more regularly, especially for frequent words and those whose foreign origin is not apparent.[19] For example, the words rahat ('comfort') and sanat ('art') take back-vowel suffixes, even though they derive from Arabic tāʼ marbūṭah.

Word-accent

Turkish words are said to have an accent on one syllable of the word. In most words the accent comes on the last syllable of the word, but there are some words, such as place names, foreign borrowings, words containing certain suffixes, and certain adverbs, where the accent comes earlier in the word.

A phonetic study by Levi (2005) shows that when a word has non-final accent, e.g. banmamak ('not to dip'), the accented syllable is higher in pitch than the following ones; it may also have slightly greater intensity (i.e. be louder) than an unaccented syllable in the same position. In longer words, such as sinirlenmeyecektiniz ('you would not get angry'), the syllables preceding the accent can also be high pitched.[20]

When the accent is final, as in banmak ('to dip'), there is often a slight rise in pitch, but with some speakers there is no appreciable rise in pitch. The final syllable is also often more intense (louder) than the preceding one. Some scholars consider such words to be unaccented.[21]

Stress or pitch?

Although most treatments of Turkish refer to the word-accent as "stress", some scholars consider it a kind of pitch accent.[22] Underhill (1986) writes that stress in Turkish "is actually pitch accent rather than dynamic stress."[23] An acoustic study, Levi (2005), agrees with this assessment, concluding that though duration and intensity of the accented syllable are significant, the most reliable cue to accent-location is the pitch of the vowel.[24] In its word-accent, therefore, Turkish "bears a great similarity with other pitch-accent languages such as Japanese, Basque, and Serbo-Croatian".[24] Similarly, Özcelik (2016), noting the difference in phonetic realisation between final and non-final accent, proposes that "Final accent in Turkish is not 'stress', but is formally a boundary tone."[25] According to this analysis therefore, only words with non-final accent are accented, and all other words are accentless.

However, not all researchers agree with this conclusion. Kabak (2016) writes: "Finally stressed words do not behave like accentless words and there is no unequivocal evidence that the language has a pitch-accent system."

Pronunciation of the accent

A non-final accent is generally pronounced with a relatively high pitch followed by a fall in pitch on the following syllable. The syllables preceding the accent may either be slightly lower than the accented syllable or on a plateau with it.[26] In words like sözcükle ('with a word'), where the first and third syllable are louder than the second, it is nonetheless the second syllable which is considered to have the accent, because it is higher in pitch, and followed by a fall in pitch.[27]

However, the accent can disappear in certain circumstances; for example, when the word is the second part of a compound, e.g. çoban salatası ('shepherd salad'), from salata, or Litvanya lokantası ('Lithuania(n) restaurant'), from lokanta.[28] In this case only the first word is accented.

If the accented vowel is final, it is often slightly higher in pitch than the preceding syllable;[29] but in some contexts or with some speakers there is no rise in pitch.[30][31][32]

Intonational tones

In addition to the accent on words, intonational tones can also be heard in Turkish. One of these is a rising boundary tone, which is a sharp rise in pitch frequently heard at the end of a phrase, especially on the last syllable of the topic of a sentence.[33] The phrase ondan sonra↑ ('after that,...'), for example, is often pronounced with a rising boundary tone on the last syllable (indicated here by an arrow).

Another intonational tone, heard in yes-no questions, is a high tone or intonational pitch-accent on the syllable before the particle mi/mu, e.g. Bu elmalar taze mi? ('Are these apples fresh?'). This tone tends to be much higher in pitch than the normal word-accent.[34]

A raised pitch is also used in Turkish to indicate focus (the word containing the important information being conveyed to the listener). "Intonation ... may override lexical pitch in Turkish".[35]

Final accent

As stated above, word-final accent is the usual pattern in Turkish:

- elma ('apple')

- evler ('houses')

When a non-preaccenting suffix is added, the accent moves to the suffix:

- elmalar ('apples')[36]

- evlerden ('from the houses')

Among the suffixes which do not add any accent to the word are the possessive suffixes -im (my), -in (your) etc.:

- arkadaşlarım ('my friends')[37]

- kızlarımız ('our daughters')

Non-final accent in Turkish words

Non-final accent in Turkish words is generally caused by the addition of certain suffixes to the word. Some of these (always of two syllables, such as -iyor) are accented themselves; others put an accent on the syllable which precedes them.

Accented suffixes

These include the following:[38]

- -iyor (continuous): geliyor ('he is coming'), geliyordular ('they were coming')

- -erek/-arak ('by'): gelerek ('by coming')

- -ince ('when'): gelince ('when he comes')

- -iver ('suddenly', 'quickly'): gidiverecek ('he will quickly go')[39]

Note that since a focus word frequently precedes a verb (see below), causing any following accent to be neutralised, these accents on verbs can often not be heard.

Pre-accenting suffixes

Among the pre-accenting suffixes are:

- -me-/-ma- (negative), e.g. korkma! ('don't be afraid!'), gelmedim ('I did not come').

- The pre-accenting is also seen in combination with -iyor: gelmiyor ('he/she/it does not come').

- However, in the aorist tense the negative is stressed: sönmez ('it will never cease').

- -le/-la ('with'): öfkeyle ('with anger, angrily')

- -ce/-ca ('-ish'): Türkçe ('Turkish')

- -ki ('that which belongs to'): benimki ('my one')[40]

The following, though written separately, are pronounced as if pre-accenting suffixes, and the stress on the final syllable of the preceding word is more pronounced than usual:

- de/da ('also', 'even'): elmalar da ('even apples')

- mi/mu (interrogative): elmalar mı? ('apples?')

Less commonly found pre-accenting suffixes are -leyin (during) and -sizin (without), e.g. akşamleyin (in the evening), gelmeksizin (without coming).[41]

Copular suffixes

Suffixes meaning 'is' or 'was' added to nouns, adjectives or participles, and which act like a copula, are pre-accenting:.[42]

- hastaydı ('he/she/it was ill')

- çocuklar ('they are children')

- Mustafa'dır ('it's Mustafa')

- öğrenciysem ('if I am a student')

Copular suffixes are also pre-accenting when added to the following participles: future (-ecek/-acak), aorist (-er/-or), and obligation (-meli):[43]

- gidecektiler ('they would go')

- saklanırdınız ('you used to hide yourself')

- bulurum ('I find')

- gidersin ('you go')

- gitmeliler ('they ought to go')[44]

Often at the end of a sentence the verb is unaccented, with all the syllables on the same pitch. Suffixes such as -di and -se/-sa are not pre-accenting if they are added directly to the verb stem:

- gitti ('he/she/it went')

- gitse ('if he goes')

This accentual pattern can disambiguate homographic words containing possessive suffixes or the plural suffix:[45]

- benim ('it's me'), vs. benim ('my')

- çocuklar ('they are children'), vs. çocuklar ('children')

Compounds

Compound nouns are usually accented on the first element only. Any accent on the second element is lost:[46]

- başbakan ('prime minister')

- başkent ('capital city')

The same is true of compound and intensive adjectives:[47]

- sütbeyaz ('milk white')

- masmavi ('very blue')

Some compounds, however, are accented on the final, for example those of the form verb-verb or subject-verb:[48]

- uyurgezer ('sleep-walker')

- hünkarbeğendi ('lamb served on aubergine purée', lit. 'the sultan liked it')

Remaining compounds have Sezer-type accent on whole word. Compound numerals are accented like one word or separately depending on speaker.

Other words with non-final accent

Certain adverbs take initial accent:[49]

- nerede? ('where?'), nereye? ('where to?'), nasıl ('how?'), hangi? ('which?')

- yarın ('tomorrow'), sonra ('afterwards'), şimdi ('now'), yine ('again')

Certain adverbs ending in -en/-an have penultimate accent unless they end in a cretic (– u x) rhythm, thus following the Sezer rule (see below):

- iktisa:den ('economically')

- tekeffülen ('by surety')

Some kinship terms are irregularly accented on the first syllable:[50]

- anne ('mother'), teyze ('maternal aunt'), hala ('paternal aunt'), dayı ('maternal uncle'), amca ('paternal uncle'), kardeş ('brother/sister'), kayın ('in-law')

Two accents in the same word

When two pre-accenting suffixes are added to a word with a non-final accent, only the first accent is pronounced:[39]

- Türkçe de ('Turkish also')

- Ankara'daydı ('he was in Ankara')

However, the accent preceding the negative -ma-/-me- may take precedence over an earlier accent:[51]

- Avrupalılaşmalı ('needing to become Europeanised')

- Avrupalılaşmamalı ('needing not to become Europeanised')

In the following pair also, the accent shifts from the object to the position before the negative:[52]

- Ali iskambil oynadı ('Ali played cards')

- Ali iskambil oynamadı ('Ali didn't play cards')

However, even the negative suffix accent may disappear if the focus is elsewhere. Thus in sentences of the kind "not A but B", the element B is focussed, while A loses its accent. Kabak (2001) gives a pitch track of the following sentence, in which the only tone on the first word is a rising boundary tone on the last syllable -lar:[53]

- Yorulmuyorlar↑, eğleniyorlardı ('They weren't getting tired, they were having fun').

In the second word, eğleniyorlardı, the highest pitch is on the syllable eğ and the accent on the suffix -iyor- almost entirely disappears.

Place names

Place names usually follow a different accentual pattern, known in the linguistics literature as "Sezer stress" (after the discoverer of the pattern, Engin Sezer).[54] According to this rule, place names that have a heavy syllable (CVC) in the antepenultimate position, followed by a light syllable (CV) in penultimate position (that is, those ending with a cretic ¯ ˘ ¯ or dactylic ¯ ˘ ˘ rhythm), have a fixed antepenultimate stress:

- Marmaris, Mercimek, İskenderun

- Ankara, Sirkeci, Torbalı, Kayseri

Most other place names have a fixed penultimate stress:

- İstanbul, Erzincan, Antalya, Edirne

- Adana, Yalova, Bakacak, Göreme

- İzmir, Bodrum, Bebek, Konya, Sivas

Some exceptions to the Sezer stress rule have been noted:[55]

(a) Many foreign place names, as well as some Turkish names of foreign origin, have fixed penultimate stress, even when they have cretic rhythm:

- Afrika, İngiltere ('England'), Meksika ('Mexico'), Belçika ('Belgium'), Avrupa ('Europe')

- Üsküdar ('Scutari'), Bergama ('Pergamon')

But Moskova ('Moscow') has Sezer stress.[56]

(b) Names ending in -iye have antepenultimate stress:

- Sultaniye, Ahmediye, Süleymaniye

(c) Names ending in -hane, -istan, -lar, -mez and some others have regular final (unfixed) stress:

- Hindistan ('India'), Bulgaristan ('Bulgaria'), Moğolistan ('Mongolia'), Yunanistan ('Greece')

- Kağıthane, Gümüşhane

- Işıklar, Söylemez

- Anadolu (but also Anadolu),[49][57] Sultanahmet, Mimarsinan

(d) Names formed from common words which already have a fixed accent retain the accent in the same place:

- Sütlüce (from sütlüce 'milky')

(e) Compounds (other than those listed above) are generally accented on the first element:

- Fenerbahçe, Gaziantep, Eskişehir, Kastamonu

- Çanakkale, Kahramanmaraş, Diyarbakır, Saimbeyli

- Kuşadası, Kandilli caddesi ('Kandilli street'), Karadeniz ('the Black Sea')[58]

(f) Other exceptions:

- Kuleli, Kınalı, Rumeli

As with all other words, names which are accented on the penultimate or antepenultimate retain the stress in the same place even when pre-accenting suffixes are added, while those accented on the final syllable behave like other final-accented words:.[56][59]

- Ankara > Ankara'dan ('from Ankara') > Ankara'dan mı? ('from Ankara?')

- Işıklar > Işıklar'dan ('from Işıklar') > Işıklar'dan mı? ('from Işıklar?')

Personal names

Turkish personal names, unlike place names, have final accent:[49]

- Hüseyin, Ahmet, Abdurrahman, Mustafa, Ayşe.

When the speaker is calling someone by their name, the accent may sometimes move up:[60]

- Ahmet, gel buraya! ('Ahmet, come here!').

Ordinary words also have a different accent in the vocative:[50]

- Öğretmenim,...! ('My teacher...!'), Efendim ('Sir!')

Some surnames have non-final stress:

Others have regular stress:

- Pamuk, Hikmet

Foreign surnames tend to be accented on the penultimate syllable, regardless of the accent in the original language:[65]

- Kenedi, Papadopulos, Vaşington, Odipus ('Oedipus')

- Ayzınhover ('Eisenhower'), Pitolemi ('Ptolemy'), Mendelson ('Mendelssohn')

- Mandela[56]

Foreign words

The majority of foreign words in Turkish, especially most of those from Arabic, have normal final stress:

- kitap ('book'), dünya ('world'), rahat ('comfortable')

The same is true of some more recent borrowings from western languages:[66]

- fotokopi ('photocopy'), istimbot ('steamboat')

On the other hand, many other foreign words follow the Sezer rules.[67] So words with a dactylic or cretic ending ( ¯ ˘ * ) often have antepenultimate accent:

- pencere ('window'), manzara ('scenery'), şevrole ('Chevrolet'), karyola ('bedframe')

Those with other patterns accordingly have penultimate accent:

- lokanta ('restaurant'), atölye ('workshop'), madalya ('medal'), masa ('table'), çanta ('bag')

- kanepe ('couch'), sinema ('cinema'), manivela ('lever'), çikolata ('chocolate')

- tornavida ('screwdriver'), fakülte ('college faculty'), jübile ('jubilee'), gazete ('newspaper').[68]

Some have irregular stress, though still either penultimate or antepenultimate:

- negatif ('negative'), acaba ('one wonders')[60]

- fabrika ('factory')

The accent on these last is not fixed, but moves to the end when non-preaccenting suffixes are added, e.g. istimbotlar ('steamboats'). However, words with non-final accent keep the accent in the same place, e.g. masalar ('tables').

Phrase-accent

The accent in phrases where one noun qualifies another is exactly the same as that of compound nouns. That is, the first noun usually retains its accent, and the second one loses it:[69]

- çoban salatası ('shepherd salad') (from salata)

- Litvanya lokantası ('Lithuania(n) restaurant') (from lokanta)

- Galata köprüsü ('the Galata bridge')

The same is true when an adjective or numeral qualifies a noun:[47][70]

- kırmızı çanta ('the red bag') (from çanta)

- yüz yıl ('a hundred years')

The same is also true of prepositional phrases:[71]

- kapıya doğru ('towards the door')

- ondan sonra ('after that')

- her zamanki gibi ('as on every occasion')

An indefinite object or focussed definite object followed by a positive verb is also accented exactly like a compound, with an accent on the object only, not the verb[72]

Focus accent

Focus also plays a part in the accentuation of subject and verb. Thus in the first sentence below, the focus (the important information which the speaker wishes to communicate) is on "a man", and only the first word has an accent while the verb is accentless; in the second sentence the focus is on "came", which has the stronger accent:[74]

- adam geldi ('a man came')

- adam geldi ('the man came')

When there are several elements in a Turkish sentence, the focussed word is often placed before the verb and has the strongest accent:.[75][76]

- Ankara'dan dün babam geldi. ('My father came from Ankara yesterday')

- Babam Ankara'dan dün geldi. ('My father came from Ankara yesterday')

For the same reason, a question-word such as kim ('who?') is placed immediately before the verb:[77]

- Bu soruyu kim çözecek? ('Who will solve this question?')

See also

Notes

- Most monosyllabic words ending in orthographic ⟨k⟩, such as pek ('quite'), are phonologically /k c/, but nearly all polysyllabic nouns with ⟨k⟩ are phonologically /ɡ/. Lewis (2001:10). Proper nouns ending in ⟨k⟩, such as İznik, are equally subject to this phonological process but have invariant orthographic rendering.

- Some dialects simplify it further into (C)V(C).

- For the terms "twofold" and "fourfold", as well as the superscript notation, see Lewis (1953:21–22). Lewis later preferred to omit the superscripts, on the grounds that "there is no need for this once the principle has been grasped" Lewis (2001:18).

- There are several other compounding auxiliaries in Turkish, such as -i ver-, -a gel-, -a yaz-.

References

- Zimmer & Orgun (1999), pp. 154–155.

- Lewis (2001), pp. 3–4, 6–7.

- Zimmer & Orgun (1999), p. 155.

- Göksel & Kerslake (2005), p. 7.

- Comrie (1997), p. ?.

- Zimmer & Orgun (1999), p. 154.

- Göksel & Kerslake (2005), p. 6.

- Göksel & Kerslake (2005), pp. 5, 7–9.

- Yavuz & Balcı (2011), p. 25.

- Göksel & Kerslake (2005), pp. 9–11.

- Göksel & Kerslake (2005), p. 10.

- Kılıç & Öğüt (2004), p. ?.

- Göksel & Kerslake (2005), pp. 10–11.

- Korkmaz (2017), pp. 69–71.

- Lewis (1953), p. 21.

- Uysal (1980:9): "Gerek Arapça ve Farsça, gerekse Batı dillerinden Türkçe'ye giren kelimeler «ince l (le)» ile biterse, son hecede kalın ünlü bulunsa bile -ki bunlar da ince okunur- eklerdeki ünlüler ince okunur: Hal-i, ihtimal-i, istiklal-i..."

- Lewis (2000), pp. 17–18.

- Lewis (2000), pp. 9–10, 18.

- Lewis (2000), p. 18.

- Levi (2005), p. 95.

- Öncelik (2014), p. 10.

- E.g. Lewis (1967), Underhill (1976), cited by Levi (2005:75)

- Underhill (1986:11), quoted in Levi (2005:75)

- Levi (2005), p. 94.

- Özcelik (2016), p. 10.

- Levi & 2005), pp. 85, 95.

- Levi & 2005), p. 85.

- Kabak (2016) fig. 11.

- Levi (2005), p. 80.

- Cf. Kabak (2001), fig. 3.

- Levi (2005:90) "Some speakers show only a plateau between the pre-accented and accented syllables."

- Cf. Forvo: arkadaşlarım

- Cf. Kabak (2001), fig. 3.

- Forvo: Bu elmalar taze mi?

- Kabak (2016).

- Forvo: elmalar

- Forvo: arkadaşlarım

- Özcelik (2014), p. 232.

- Inkelas & Orgun (2003), p. 142.

- Kabak & Vogel (2001), p. 328.

- Öncelik (2014), p. 251.

- Kabak & Vogel (2001), pp. 330–1.

- Kabak & Vogel (2001), p. 329.

- Revithiadou et al. (2006), p. 5.

- Halbout & Güzey (2001), pp. 56–58.

- Kabak & Vogel (2001), pp. 333, 339.

- Kabak & Vogel (2001), p. 339.

- Kamali & İkizoğlu, p. 3.3.

- Dursunoğlu (2006), p. 272.

- Börekçi (2005), p. 191.

- Revithiadou et al. (2006), p. 6.

- Kamali & Samuels (2008), p. 4.

- Kabak (2001), fig. 1.

- Sezer (1981), p. ?.

- Inkelas & Orgun (2003), p. 142–152.

- Kabak & Vogel (2001), p. 325.

- Forvo: Anadolu

- Kabak & Vogel (2001), p. 337.

- Öncelik (2016), p. 17.

- Kabak & Vogel (2001), p. 316.

- Forvo: Erdoğan

- Forvo: Erbakan

- Forvo: İnönü

- Forvo: Atatürk

- Sezer (1981), pp. 64–5.

- Inkelas & Orgun (2003), p. 143.

- Sezer (1981), pp. 65–6.

- Öncelik (2014), p. 231.

- Kabak (2016) , fig. 11.

- Dursunoğlu (2006), p. 273.

- Kamali & İkizoğlu, p. ?.

- Inkelas & Orgun (2003), p. 141.

- Kabak & Vogel (2001), p. 338.

- Öncelik (2016), p. 20.

- Dursunoğlu (2006), pp. 273–4.

- Öncelik (2016), pp. 19–20.

- Dursunoğlu (2006), p. 274.

Bibliography

- Börekçi, Muhsine (2005), "Türkcede Vurgu-Tonlama-Ölçü-Anlam İlişkisi (The Relationships Between The Stress, Intonation, Meter and Sound in the Turkish Language" (PDF), Kazım Karabekir Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi (in Turkish), 12, pp. 187–207

- Comrie, Bernard (1997). "Turkish Phonology". In Kaye, Alan S.; Daniel, Peter T. (eds.). Phonologies of Asia and Africa. 2. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. pp. 883–898. ISBN 978-1-57506-019-4.

- Dursunoğlu, Halit (2006), "Türkiye Türkçesinde Vurgu (Stress in the Turkish of Turkey)", Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi (in Turkish), 7 (1): 267–276

- Göksel, Asli; Kerslake, Celia (2005), Turkish: a comprehensive grammar, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415114943

- Halbout, Dominique; Güzey, Gönen (2001). Parlons turc (in French). Paris: L'Harmattan.

- Inkelas, Sharon; Orgun, Cemil Orhan (2003). "Turkish stress: A review" (PDF). Phonology. 20 (1): 139–161. doi:10.1017/s0952675703004482. S2CID 16215242.

- Kabak, Barış; Vogel, Irene (2001), "The phonological word and stress assignment in Turkish" (PDF), Phonology, 18 (3): 315–360, doi:10.1017/S0952675701004201

- Kabak, Barış (2016), "Refin(d)ing Turkish stress as a multifaceted phenomenon" (PDF), Second Conference on Central Asian Languages and Linguistics (ConCALL52)., Indiana University

- Kamali, Beste; İkizoğlu, Didem (2012), "Against compound stress in Turkish"", Proceedings of 16th International Conference on Turkish Linguistics, Middle East Technical University, Ankara

- Kamali, Beste; Samuels, Bridget (2008), "Hellenistic Athens and her Philosophers" (PDF), 3rd Conference on Tone & Intonation in Europe, Lisbon

- Kılıç, Mehmet Akif; Öğüt, Fatih (2004). "A high unrounded vowel in Turkish: is it a central or back vowel?" (PDF). Speech Communication. 43 (1–2): 143–154. doi:10.1016/j.specom.2004.03.001 – via Elsevier ScienceDirect.

- Korkmaz, Zeynep (2017). Türkiye Türkçesi Grameri: Şekil Bilgisi (in Turkish). Ankara: Türk Dil Kurumu.

- Levi, Susannah V. (2005). "Acoustic correlates of lexical accent in Turkish". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 35 (1): 73–97. doi:10.1017/S0025100305001921.

- Lewis, Geoffrey (1953). Teach Yourself Turkish. English Universities Press. ISBN 978-0-340-49231-4.

- Lewis, Geoffrey (2001). Turkish Grammar. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-870036-9.

- Özcelik, Öner (2014). "Prosodic faithfulness to foot edges: the case of Turkish stress" (PDF). Phonology. 31 (2): 229–269. doi:10.1017/S0952675714000128.

- Özcelik, Öner (2016). "The Foot is not an obligatory constituent of the Prosodic Hierarchy: 'stress' in Turkish, French and child English" (PDF). The Linguistic Review. 34 (1): 229–269. doi:10.1515/tlr-2016-0008. S2CID 170302676.

- Petrova, Olga; Plapp, Rosemary; Ringen, Ringen; Szentgyörgyi, Szilárd (2006), "Voice and aspiration: Evidence from Russian, Hungarian, German, Swedish, and Turkish", The Linguistic Review, 23: 1–35, doi:10.1515/TLR.2006.001, S2CID 42712078

- Revithiadou, Anthi; Kaili, Hasan; Prokou, Sophia; Tiliopoulou, Maria-Anna (2006), "Turkish accentuation revisited: Α compositional approach to Turkish stress" (PDF), Advances in Turkish Linguistics: Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Turkish Linguistics, Dokuz Eylül Yayınları, İzmir, pp. 37–50

- Sezer, Engin (1981), "On non-final stress in Turkish" (PDF), Journal of Turkish Studies, 5: 61–69

- Underhill, Rorbert (1976). Turkish grammar. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Underhill, Rorbert (1986), "Turkish", in Slobin, Dan; Zimmer, Karl (eds.), Studies in Turkish Linguistics, Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 7–21

- Uysal, Sermet Sami (1980). Yabancılara Türk dilbilgisi (in Turkish). 3. Sermet Matbaası.

- Yavuz, Handan; Balcı, Ayla (2011), Turkish Phonology and Morphology (PDF), Eskişehir: Anadolu Üniversitesi, ISBN 978-975-06-0964-0

- Zimmer, Karl; Orgun, Orhan (1999), "Turkish" (PDF), Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 154–158, ISBN 0-521-65236-7

Further reading

- Inkelas, Sharon. (1994). Exceptional stress-attracting suffixes in Turkish: Representations vs. the grammar.

- Kaisse, Ellen. (1985). Some theoretical consequences of stress rules in Turkish. In W. Eilfort, P. Kroeber et al. (Eds.), Papers from the general session of the Twenty-first regional meeting (pp. 199–209). Chicago: Chicago Linguistics Society.

- Lees, Robert. (1961). The phonology of Modern Standard Turkish. Indiana University publications: Uralic and Altaic series (Vol. 6). Indiana University Publications.

- Lightner, Theodore. (1978). The main stress rule in Turkish. In M. A. Jazayery, E. Polomé et al. (Eds.), Linguistic and literary studies in honor of Archibald Hill (Vol. 2, pp. 267–270). The Hague: Mouton.

- Swift, Lloyd B. (1963). A reference grammar of Modern Turkish. Indiana University publications: Uralic and Altaic series (Vol. 19). Bloomington: Indiana University Publications.