Umbilical hernia

An umbilical hernia is a health condition where the abdominal wall behind the navel is damaged. It may cause the navel to bulge outwards—the bulge consisting of abdominal fat from the greater omentum or occasionally parts of the small intestine. The bulge can often be pressed back through the hole in the abdominal wall, and may "pop out" when coughing or otherwise acting to increase intra-abdominal pressure. Treatment is surgical, and surgery may be performed for cosmetic as well as health-related reasons.

| Umbilical hernia | |

|---|---|

%252C_1967.jpg.webp) | |

| Children with umbilical hernias, Sierra Leone (West Africa), 1967. | |

| Specialty | General surgery |

Signs and symptoms

A hernia is present at the site of the umbilicus (commonly called a navel or belly button) in newborns; although sometimes quite large, these hernias tend to resolve without any treatment by around the age of 2–3 years.[1] Obstruction and strangulation of the hernia is rare because the underlying defect in the abdominal wall is larger than in an inguinal hernia of the newborn. The size of the base of the herniated tissue is inversely correlated with risk of strangulation (i.e., a narrow base is more likely to strangulate).

Babies are prone to this malformation because of the process during fetal development by which the abdominal organs form outside the abdominal cavity, later returning into it through an opening which will become the umbilicus.[2]

Hernias may be asymptomatic and present only as a bulge of the umbilicus. Symptoms may develop when the contracting abdominal wall causes pressure on the hernia contents. This results in abdominal pain or discomfort. These symptoms may be worsened by the patient lifting or straining.

Causes

The causes of umbilical hernia are congenital and acquired malformation, but an apparent third cause is really a cause of a different type, a paraumbilical hernia.

Congenital

Congenital umbilical hernia is a congenital malformation of the navel (umbilicus). Among adults, it is three times more common in women than in men; among children, the ratio is roughly equal.[3] It is also found to be more common in children of African descent.[4][5][6]

Acquired

An acquired umbilical hernia directly results from increased intra-abdominal pressure caused by obesity, heavy lifting, a long history of coughing, or multiple pregnancies.[7][8] Another type of acquired umbilical hernias are incisional hernias, which are hernia developing in a scar following abdominal surgery, e.g. after insertion of laparoscopy trocars through the umbilicus.

Paraumbilical

Importantly, an umbilical hernia must be distinguished from a paraumbilical hernia, which occurs in adults and involves a defect in the midline near to the umbilicus, and from omphalocele.

Diagnosis

Navels with the umbilical tip protruding past the umbilical skin ("outies") are often mistaken for umbilical hernias, which are a completely different shape. Treatment for cosmetic purposes is not necessary, unless there are health concerns such as pain, discomfort or incarceration of the hernia content. Incarceration refers to the inability to reduce the hernia back into the abdominal cavity. Prolonged incarceration can lead to tissue ischemia (strangulation) and shock when untreated.

Umbilical hernias are common. With a study involving Africans, 92% of children had protrusions, 49% of adults, and 90% of pregnant women. However, a much smaller number actually suffered from hernias: only 23% of children, 8% of adults, and 15% of pregnant women.[4]

When the orifice is small (< 1 or 2 cm), 90% close within 3 years (some sources state 85% of all umbilical hernias, regardless of size), and if these hernias are asymptomatic, reducible, and don't enlarge, no surgery is needed (and in other cases it must be considered).

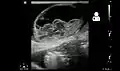

Ultrasound showing an incarcerated umbilical hernia[9]

Ultrasound showing an incarcerated umbilical hernia[9]

Treatment

Children

In some communities mothers routinely push the small bulge back in and tape a coin over the palpable hernia hole until closure occurs. This practice is not medically recommended as there is a small risk of trapping a loop of bowel under part of the coin resulting in a small area of ischemic bowel. This "fix" does not help and germs may accumulate under the tape, causing infection. The use of bandages or other articles to continuously reduce the hernia is not evidence-based.

An umbilical hernia can be fixed in two different ways. The surgeon can opt to stitch the walls of the abdomen or he/she can place mesh over the opening and stitch it to the abdominal walls. The latter is of a stronger hold and is commonly used for larger defects in the abdominal wall. Most surgeons will not repair the hernia until 5–6 years after the baby is born. Most umbilical hernias in infants and children close spontaneously and rarely have complications of gastrointestinal-content incarcerations.[10]

How far the projection of the swelling extends from the surface of the abdomen (the belly) varies from child to child. In some, it may be just a small protrusion; in others it may be a large rounded swelling that bulges out when the baby cries. It may hardly be visible when the child is quiet and or sleeping.

Normally, the abdominal muscles converge and fuse at the umbilicus during the formation stage, however, in some cases, there remains a gap where the muscles do not close and through this gap the inner intestines come up and bulge under the skin, giving rise to an umbilical hernia. The bulge and its contents can easily be pushed back and reduced into the abdominal cavity.

In contrast to an inguinal hernia, the complication incidence is very low, and in addition, the gap in the muscles usually closes with time and the hernia disappears on its own. The treatment of this condition is essentially conservative: observation allowing the child to grow up and see if it disappears. Operation and closure of the defect is required only if the hernia persists after the age of 3 years or if the child has an episode of complication during the period of observation like irreducibility, intestinal obstruction, abdominal distension with vomiting, or red shiny painful skin over the swelling. Surgery is always done under anesthesia. The defect in the muscles is defined and the edges of the muscles are brought together with sutures to close the defect. In general, the child needs to stay in the hospital for 1 day[11] and the healing is complete within 8 days.

At times, there may be a fleshy red swelling seen in the hollow of the umbilicus that persists after the cord has fallen off. It may bleed on touch, or may stain the clothes that come in contact with it. This needs to be shown to a pediatric surgeon. This is most likely to be an umbilical polyp and the therapy is to tie it at the base with a stitch so that it falls off and there is no bleeding. Alternatively, it may be an umbilical granuloma that responds well to local application of dry salt or silver nitrate but may take a few weeks to heal and dry.[12]

Adults

Many hernias never cause any problems, and do not require any treatment at all. However, because the risk of complications with age are higher and the hernia is unlikely to resolve without treatment, surgery is usually recommended.[2]

Usually hernia has content of bowel, abdominal fat or omentum, tissue that normally would reside inside the abdominal cavity if it wasn't for the hernia. In some cases, the content gets trapped in the hernia sac, outside the abdominal wall. The blood flow to this trapped tissue may be compromised, or the content even strangulated in some cases. Depending on the severity and duration of blood flow compromise, it can cause some pain and discomfort. Usually the situation resolves itself, when the protrusion of content is returned to the abdominal cavity. Sometimes this needs to be done by a doctor at the ICU.[13]

If the hernia content get trapped combined with severe pain, inability to perform bowel movement or pass gas, swelling, fever, nausea and/or discoloration over the area, it could be signs of a prolonged compromise in blood flow of the hernia content. If so, emergency surgery is often required, since prolonged compromise in blood flow otherwise threatens organ integrity.[13]

Hernias that are symptomatic and disturb daily activity, or hernias that have had episodes of threatening incarceration, preventive surgical treatment can be considered. The surgery is performed under anaesthesia, while the surgeon identifies the edges of the defect and bring them together permanently using either suture or mesh.[14] Small umbilical hernias are often successfully repaired with suture, while larger hernias may require a suitable mesh,[15] although some surgeons advocate mesh treatment for most hernias. The most common complications for both techniques are superficial wound infections, recurrence of the hernia[16] and some people experience pain from the surgical site.[17]

References

- Lissauer T, Clayden G (2007). Illustrated Textbook of Paediatrics (3rd ed.). Edinburgh: Mosby Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7234-3397-2.

- "Umbilical hernia repair". NHS choices. UK.GOV. 2017-10-23. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- Abdominal Hernias at eMedicine

- Meier DE, OlaOlorun DA, Omodele RA, Nkor SK, Tarpley JL (May 2001). "Incidence of umbilical hernia in African children: redefinition of "normal" and reevaluation of indications for repair". World Journal of Surgery. 25 (5): 645–8. doi:10.1007/s002680020072. PMID 11369993.

- Arca MJ (November 2016). "APSA - Umbilical Conditions" (Website). APSA - Family and Parent Resources. Oakbrook Terrace, Illinois, USA: American Pediatric Surgical Association. Retrieved November 5, 2017.

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Umbilical hernia repair

- Mayo Clinic staff. "Umbilical hernia: Causes - MayoClinic.com". Retrieved 2010-03-31.

- "Hernia: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". 2014-10-25. Retrieved 2016-07-15.

- "UOTW #44 - Ultrasound of the Week". Ultrasound of the Week. 18 April 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- Papagrigoriadis S, Browse DJ, Howard ER (December 1998). "Incarceration of umbilical hernias in children: a rare but important complication". Pediatric Surgery International. 14 (3): 231–2. doi:10.1007/s003830050497. PMID 9880759.

- Barreto L, Khan AR, Khanbhai M, Brain JL (July 2013). "Umbilical hernia". BMJ. 347: f4252. doi:10.1136/bmj.f4252. PMID 23873946.

- "Child with Umbilical Swellings/Hernia". Archived from the original on April 7, 2013. Retrieved 2013-10-10.

- Summers A (March 2014). "Congenital and acquired umbilical hernias: examination and treatment". Emergency Nurse. 21 (10): 26–8. doi:10.7748/en2014.03.21.10.26.e1260. PMID 24597817.

- Nguyen MT, Berger RL, Hicks SC, Davila JA, Li LT, Kao LS, Liang MK (May 2014). "Comparison of outcomes of synthetic mesh vs suture repair of elective primary ventral herniorrhaphy: a systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA Surgery. 149 (5): 415–21. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2013.5014. PMID 24554114.

- Dalenbäck J, Andersson C, Ribokas D, Rimbäck G (August 2013). "Long-term follow-up after elective adult umbilical hernia repair: low recurrence rates also after non-mesh repairs". Hernia. 17 (4): 493–7. doi:10.1007/s10029-012-0988-0. PMID 22971796.

- Winsnes A, Haapamäki MM, Gunnarsson U, Strigård K (August 2016). "Surgical outcome of mesh and suture repair in primary umbilical hernia: postoperative complications and recurrence". Hernia. 20 (4): 509–16. doi:10.1007/s10029-016-1466-x. PMID 26879081.

- Christoffersen MW, Helgstrand F, Rosenberg J, Kehlet H, Strandfelt P, Bisgaard T (April 2015). "Long-term recurrence and chronic pain after repair for small umbilical or epigastric hernias: a regional cohort study". American Journal of Surgery. 209 (4): 725–32. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.05.021. PMID 25172168.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Umbilical hernia. |