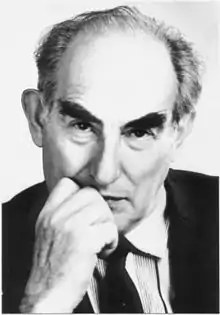

Vitaly Ginzburg

Vitaly Lazarevich Ginzburg, ForMemRS[1] (Russian: Вита́лий Ла́заревич Ги́нзбург; 4 October 1916 – 8 November 2009) was a Soviet and Russian theoretical physicist, astrophysicist, Nobel laureate, a member of the Soviet and Russian Academies of Sciences and one of the fathers of the Soviet hydrogen bomb.[2][3] He was the successor to Igor Tamm as head of the Department of Theoretical Physics of the Lebedev Physical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences (FIAN), and an outspoken atheist.[4]

Vitaly Ginzburg | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Vitaly Lazarevich Ginzburg 4 October 1916 Moscow, Russian Empire |

| Died | 8 November 2009 (aged 93) Moscow, Russia |

| Resting place | Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow |

| Nationality | Russia |

| Alma mater | Moscow State University (MS 1938) (PhD 1942) |

| Known for | Ginzburg–Landau theory Ginzburg criterion Transition radiation Undulator |

| Spouse(s) | Olga Zamsha Ginzburg (1937–1946; divorced; 1 child) Nina Yermakova Ginzburg (m. 1946) |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Theoretical physics |

| Institutions | P. N. Lebedev Physical Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences |

| Doctoral advisor | Igor Tamm |

| Doctoral students | Viatcheslav Mukhanov |

Biography

Vitaly Ginzburg was born to a Jewish family in Moscow in 1916, the son of an engineer Lazar Yefimovich Ginzburg and a doctor Augusta Wildauer, and graduated from the Physics Faculty of Moscow State University in 1938. He defended his candidate's (Ph.D.) dissertation in 1940, and his doctor's dissertation in 1942. In 1944, he became a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Among his achievements are a partially phenomenological theory of superconductivity, the Ginzburg–Landau theory, developed with Lev Landau in 1950;[5] the theory of electromagnetic wave propagation in plasmas (for example, in the ionosphere); and a theory of the origin of cosmic radiation. He is also known to biologists as being part of the group of scientists that helped bring down the reign of the politically connected anti-Mendelian agronomist Trofim Lysenko, thus allowing modern genetic science to return to the USSR.[6]

In 1937, Ginzburg married Olga Zamsha. In 1946, he married his second wife, Nina Ginzburg (nee Yermakova), who had spent more than a year in custody on fabricated charges of plotting to assassinate the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin.[7]

Ginzburg was the editor-in-chief of the scientific journal Uspekhi Fizicheskikh Nauk.[3] He also headed the Academic Department of Physics and Astrophysics Problems, which Ginzburg founded at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology in 1968.[8]

Ginzburg identified as a secular Jew, and following the collapse of communism in the former Soviet Union, he was very active in Jewish life, especially in Russia, where he served on the board of directors of the Russian Jewish Congress. He is also well known for fighting anti-Semitism and supporting the state of Israel.[9]

In the 2000s (decade), Ginzburg was politically active, supporting the Russian liberal opposition and human rights movement.[10] He defended Igor Sutyagin and Valentin Danilov against charges of espionage put forth by the authorities. On 2 April 2009, in an interview to the Radio Liberty Ginzburg denounced the FSB as an institution harmful to Russia and the ongoing expansion of its authority as a return to Stalinism.[11]

Ginzburg worked at the P. N. Lebedev Physical Institute of Soviet and Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow since 1940. Russian Academy of Sciences is a major institution where mostly all Nobel Prize laureates of physics from Russia have done their studies and/or research works.[12]

Stance on religion

Ginzburg was an avowed atheist, both under the militantly atheist Soviet government and in post-Communist Russia when religion made a strong revival.[13] He criticized clericalism in the press and wrote several books devoted to the questions of religion and atheism.[14][15] Because of this, some Orthodox Christian groups denounced him and said no science award could excuse his verbal attacks on the Russian Orthodox Church.[16] He was one of the signers of the Open letter to the President Vladimir V. Putin from the Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences against clericalisation of Russia.

Death

A spokeswoman for the Russian Academy of Sciences, announced that Ginzburg died in Moscow on 8 November 2009 from cardiac arrest.[2][17] He had been suffering from ill health for several years,[17] and three years before his death said "In general, I envy believers. I am 90, and [am] being overcome by illnesses. For believers, it is easier to deal with them and with life's other hardships. But what can be done? I cannot believe in resurrection after death."[17]

Prime Minister of Russia Vladimir Putin sent his condolences to Ginzburg's family, saying "We bid farewell to an extraordinary personality whose outstanding talent, exceptional strength of character and firmness of convictions evoked true respect from his colleagues".[17] President of Russia Dmitry Medvedev, in his letter of condolences, described Ginzburg as a "top physicist of our time whose discoveries had a huge impact on the development of national and world science."[18]

Ginzburg was buried on 11 November in the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow, the resting place of many famous politicians, writers and scientists of Russia.[2]

Honors and awards

- Medal "For Valiant Labour in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945" (1946)

- Medal "In Commemoration of the 800th Anniversary of Moscow" (1948)

- Stalin Prize in 1953

- Order of Lenin (1954)

- Order of the Badge of Honour, twice (1954, 1975)

- Order of the Red Banner of Labour, twice (1956, 1986)

- Lenin Prize in 1966

- Medal "For Valiant Labour. To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the birth of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin" (1970)

- Marian Smoluchowski Medal (1984)

- Elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1987[1]

- Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1991

- Wolf Prize in Physics in 1994/5

- Vavilov Gold Medal (1995) – for outstanding work in physics, including a series of papers on the theory of radiation by uniformly moving sources

- Lomonosov Gold Medal in 1995 – for outstanding achievement in the field of theoretical physics and astrophysics

- 3rd class (3 October 1996) – for outstanding scientific achievements and the training of highly qualified personnel

- Elected a Fellow of the American Physical Society in 2003. [19]

- Nobel Prize in Physics in 2003, together with Alexei Alexeyevich Abrikosov and Anthony James Leggett for their "pioneering contributions to the theory of superconductors and superfluids"[20]

- Order "For Merit to the Fatherland", 1st class (4 October 2006) – for outstanding contribution to the development of national science and many years of fruitful activity

References

- Longair, M. S. (2011). "Vitaly Lazarevich Ginzburg. 4 October 1916 – 8 November 2009". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 57: 129–146. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2011.0002.

- Thomas H. Maugh II (November 10, 2009). "Vitaly Ginzburg dies at 93; Nobel Prize-winning Russian physicist". Los Angeles Times.

- "Vitaly Lazarevich Ginzburg — editor in chief of UFN".

- Nikonov, Vyacheslav (September 30, 2004). "Physicists have nothing to do with miracles". Social Sciences (3): 148–150. Retrieved September 9, 2007.

- Ledenyov, Dimitri O.; Ledenyov, Viktor O. (2012). "Nonlinearities in Microwave Superconductivity". arXiv:1206.4426 [cond-mat.supr-con].CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Medvedev, Zhores (1969). The Rise and Fall of T.D. Lysenko. New York: Columbia University Press.

- "Виталий Гинзбург: с Ландау трудно было спорить — Юрий Медведев."Уравнение Гинзбурга – Ландау" — Российская Газета — Академику и нобелевскому лауреату Виталию Гинзбургу исполняется 90 лет. Накануне юбилея он рассказал в интервью "РГ", как стал физиком-теоретиком, будучи "плохим" математиком, и почему он брал расписки со своего друга и учителя – знаменитого Льва Ландау, с которым вместе работал над сверхпроводимостью. Именно за эту работу Гинзбург впоследствии получил Нобелевскую премию. "Общаясь с Ландау, я много думал о его феномене, о пределах возможностей человека, огромных резервах мозга", – признался он". Rg.ru. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- "About Academic Department of Physics and Astrophysics Problems" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 21 June 2007.

- Hein, Avi. "Vitaly Ginzburg". Jewish Virtual Library.

- "Russia: Religious revival troubles Vitaly Ginzburg". University World News. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- Mikhail Sokolov. "2009 RFE/RL, Inc". Svobodanews.ru. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- "Nobel Prize laureates affiliated with the Russian Academy of Sciences".

- http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/2003/ginzburg-autobio.html

- Ginzburg, Vitaly (2009). "About atheism, religion and secular humanism". Moscow: FIAN. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Церковь ждет исповеди академиков (in Russian).

- Клирики против физика. Православные требуют привлечь к ответственности академика Гинзбурга. Grani.ru (in Russian). July 24, 2007.

- Osipovich, Alexander (November 9, 2009). "Russian bomb physicist Ginzburg dead at 93". AFP. Archived from the original on April 13, 2010. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- "Dmitry Medvedev sent his condolences to the family of Nobel Prize Winner Vitaly Ginzburg following the scientist's passing". President of Russia: Official Web Portal. November 9, 2009. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- "APS Fellow Archive". APS. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2003". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

External links

| Wikinews has related news: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Vitaly Ginzburg |

- Vitaly L. Ginzburg on Nobelprize.org

including the Nobel Lecture On Superconductivity and Superfluidity

including the Nobel Lecture On Superconductivity and Superfluidity - Ginzburg's homepage

- Curriculum Vitae

- Open letter to the President of the Russian Federation Vladimir V. Putin

- Obituary The Daily Telegraph 11 Nov 2009.

- Obituary The Independent November 14, 2009 (by Martin Childs).

- (in Russian) Biography

- (in Russian) Obituary