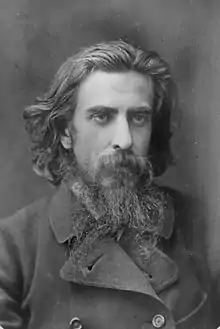

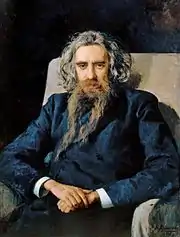

Vladimir Solovyov (philosopher)

Vladimir Sergeyevich Solovyov (Russian: Влади́мир Серге́евич Соловьёв; January 28 [O.S. January 16] 1853 – August 13 [O.S. July 31] 1900), a Russian philosopher, theologian, poet, pamphleteer, and literary critic, played a significant role in the development of Russian philosophy and poetry at the end of the 19th century and in the spiritual renaissance of the early-20th century.

Vladimir Solovyov | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 28, 1853 |

| Died | August 13, 1900 (aged 47) Uzkoye, Moscow Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Russian philosophy |

| School | Christian mysticism, Russian symbolism, Russian Schellingianism[1] |

Main interests | Theology |

Notable ideas | Revived and expanded the idea of Sophia, the feminine manifestation of Divine Wisdom in Orthodox theology |

Life and work

He was born in Moscow;[3] the son of the historian Sergey Mikhaylovich Solovyov (1820–1879), and the brother of historical novelist Vsevolod Solovyov (1849-1903) and the poet Polyxena Solovyova (1867-1924).[4] His mother Polyxena Vladimirovna belonged to a Polish origin family and had, among her ancestors, the thinker Gregory Skovoroda (1722–1794).[5]

In his teens, Solovyov renounced Eastern Orthodoxy for nihilism, but later, his disapproval of positivism[6] saw him begin to express views that were in line with those of the Orthodox Church.[6] Solovyov studied at the University of Moscow, and his philosophy professor was Pamfil Yurkevich.[7]

In his The Crisis of Western Philosophy: Against the Positivists, Solovyov discredited the positivists' rejection of Aristotle's essentialism, or philosophical realism. In Against the Positivists, he took the position of intuitive noetic comprehension, or insight. He saw consciousness as integral (see the Russian term sobornost) and requiring both phenomenon (validated by dianonia) and noumenon validated intuitively.[6] Positivism, according to Solovyov, validates only the phenomenon of an object, denying the intuitive reality that people experience as part of their consciousness.[6] As Solovyov's basic philosophy rests on the idea that the essence of an object (see essentialism) can be validated only by intuition and that consciousness as a single organic whole is done in part by reason or logic but in completeness by (non-dualist) intuition. Solovyov was partially attempting to reconcile the dualism (subject-object) found in German idealism.

Vladimir Solovyov became a friend and confidant of Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821–1881). In opposition to his friend, Solovyov was sympathetic to the Roman Catholic Church. He favoured the healing of the schism (ecumenism, sobornost) between the Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches. It is clear from Solovyov's work that he accepted papal primacy over the Universal Church,[8][9][10] but there is not enough evidence, at this time, to support the claim that he ever officially embraced Roman Catholicism.

As an active member of Society for the Promotion of Culture Among the Jews of Russia, he spoke Hebrew and struggled to reconcile Judaism and Christianity. Politically, he became renowned as the leading defender of Jewish civil rights in tsarist Russia in the 1880s. Solovyov also advocated for his cause internationally and published a letter in The London Times pleading for international support for his struggle.[11] The Jewish Encyclopedia describes him as "a friend of the Jews" and states that "Even on his death-bed he is said to have prayed for the Jewish people".[12]

Solovyov's attempts to chart a course of civilization's progress toward an East-West Christian ecumenicism developed an increasing bias against Asian cultures which he initially studied with great interest. He dismissed the Buddhist concept of Nirvana as a pessimistic nihilistic "nothingness" which was antithetical to salvation, no better than Gnostic dualism. [13] Solovyov spent his final years obsessed with fear of the "Yellow Peril", warning that soon the Asian peoples, especially the Chinese, would invade and destroy Russia.[14] Solovyov further elaborated in his apocalyptic short story "Tale of the Antichrist" published in the Nedelya newspaper on February 27, 1900, in which China and Japan join forces to conquer Russia.[14] His 1894 poem Pan-Mongolism, whose opening lines serve as epigraph to the story, was widely seen as predicting the coming Russo-Japanese War.[15]

Solovyov never married or had children, but he pursued idealized relationships as immortalized in his spiritual love poetry, including with two women named Sophia.[16] He rebuffed the advances of mystic Anna Schmidt, who claimed to be his divine partner.[17] In his later years, Solovyov became a vegetarian but ate fish occasionally. He often lived alone for months without a servant and would work into the night.[18]

Influence

It is widely held that Solovyov was one of the sources for Dostoevsky's characters Alyosha Karamazov and Ivan Karamazov in The Brothers Karamazov.[19] Solovyov's influence can also be seen in the writings of the Symbolist and Neo-Idealist writers of the later Russian Soviet era. His book The Meaning of Love can be seen as one of the philosophical sources of Leo Tolstoy's The Kreutzer Sonata (1889). It was also the work in which he introduced the concept of 'syzygy', to denote 'close union'.[20] Another legacy of Solovyov can be found in symphonic metal band Therion's 2018 triple album, Beloved Antichrist.[21]

Sophiology

Solovyov compiled a philosophy based on Hellenistic philosophy (see Plato, Aristotle and Plotinus) and early Christian tradition with Buddhist and Hebrew Kabbalistic elements (Philo of Alexandria). He also studied Gnosticism and the works of the Gnostic Valentinus.[22] His religious philosophy was syncretic and fused philosophical elements of various religious traditions with Orthodox Christianity and his own experience of Sophia.

Solovyov described his encounters with the entity Sophia in his works, such as Three Encounters and Lectures on Godmanhood. His fusion was driven by the desire to reconcile and/or unite with Orthodox Christianity the various traditions by the Russian Slavophiles' concept of sobornost. His Russian religious philosophy had a very strong impact on the Russian Symbolist art movements of his time.[22] His teachings on Sophia, conceived as the merciful unifying feminine wisdom of God comparable to the Hebrew Shekinah or various goddess traditions,[23] have been deemed a heresy by Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia and as unsound and unorthodox by the Patriarchate of Moscow.[24]

Sobornost

Solovyov sought to create a philosophy that could through his system of logic or reason reconcile all bodies of knowledge or disciplines of thought, and fuse all conflicting concepts into a single system. The central component of this complete philosophic reconciliation was the Russian Slavophile concept of sobornost (organic or spontaneous order through integration, which is related to the Russian word for 'catholic'). Solovyov sought to find and validate common ground, or where conflicts found common ground, and, by focusing on this common ground, to establish absolute unity and/or integral[25] fusion of opposing ideas and/or peoples.[26]

Professor Joseph Papin, in his work Doctrina De Bono Perfecto, Eiusque Systemate N.O. Losskij Personalistico Applicatio (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1946) gives insight into the thoughts of Vladimir Soloviev. After teaching at the University of Notre Dame, Papin founded the Theology Institute at Villanova University. He edited publications from the first six symposia of the Theology Institute (1968-1974). The idea of Sobornost was prominent in the VI volume: The Church and Human Society at the Threshold of the Third Millennium (Villanova University Press, 1974). His own in-depth scholarly contribution was entitled: "From Collegiality and Sobornost to Church Unity." In volume V of the Symposia, Papin published a profound study on Soloviev in relation to the future development of Christianity, a community of love: "Eschaton in the Vision of the Russian Newman (Soloviev)" in The Eschaton: A Community of Love, (ed. Joseph Papin, Volume V, Villanova university Press, 1971, pp. 1–55). The Dean of Harvard Divinity School, Krister Stendahl, gave his highest praise to Papin for his efforts in overcoming the divisions separating Christians: "It gladdens me that you will be honored at the time of having completed a quarter century of teaching us all. Your vision of and your dogged insistence on a truly catholic i.e. ecumenical future of the church and theology has been one of the forces that have broken through the man-made walls of partition. . ." [Transcendence and Immanence, Reconstruction in the Light of Process Thinking, Volume I, ed. Joseph Armenti, St Meinrad: The Abbey Press, 1972, p. 5). At the time of his death, United States President Ronald Reagan along with theologians, philosophers, poets, and dignitaries from around the world wrote to Dr. Joseph Armenti praising the life and work of Reverend Joseph Papin. See: “President Reagan Leads International Homage to Fr. Papin in Memorial,” JEDNOTA, 1983, page 8).

Death

Intense mental work shattered Solovyov's health.[27] He died at the Moscow estate of Nikolai Petrovitch Troubetzkoy, where a relative of the latter, Sergei Nikolaevich Trubetskoy, was living.[27][28] Solovyov was apparently a homeless pauper in 1900. He left his brother, Mikhail Sergeevich, and several colleagues to defend and promote his intellectual legacy. He is buried at Novodevichy Convent.

Quotes

"But if the faith communicated by the Church to Christian humanity is a living faith, and if the grace of the sacraments is an effectual grace, the resultant union of the divine and the human cannot be limited to the special domain of religion, but must extend to all Man's common relationships and must regenerate and transform his social and political life."[29]

Bibliography

- The Burning Bush: Writings on Jews and Judaism, Compiled 2016 by Lindisfarne Books, ISBN 0-940262-73-8 ISBN 978-0-940262-73-7

- The Crisis of Western Philosophy: Against the Postivists, 1874. Reprinted 1996 by Lindisfarne Books, ISBN 0-940262-73-8 ISBN 978-0-940262-73-7

- The Philosophical Principles of Integral Knowledge (1877)

- The Critique of Abstract Principles (1877–80)

- Lectures on Divine Humanity (1877–91)

- The Russian Idea, 1888. Translation published in 2015 by CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, ISBN 1508510075 ISBN 978-1508510079

- A Story of Anti-Christ (novel), 1900. Reprinted 2012 by Kassock Bros. Publishing Co., ISBN 1475136838 ISBN 978-1475136838

- The Justification of the Good, 1918. Reprinted 2010 by Cosimo Classics, ISBN 1-61640-281-4 ISBN 978-1-61640-281-5

- The Meaning of Love. Reprinted 1985 by Lindisfarne Books, ISBN 0-89281-068-8 ISBN 978-0-89281-068-0

- War, Progress, and the End of History: Three Conversations, Including a Short Story of the Anti-Christ, 1915. Reprinted 1990 by Lindisfarne Books, ISBN 0-940262-35-5 ISBN 978-0-940262-35-5

- Russia and the Universal Church, . Reprinted 1948 by G. Bles. (Abridged version: The Russian Church and the Papacy, 2002, Catholic Answers, ISBN 1-888992-29-8 ISBN 978-1-888992-29-8)

References

Footnotes

- Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy (1998): "Schellingianism, Russian".

- Vladimir Sergeyevich Solovyov, The Meaning of Love, 1985, p. 20.

- Dahm 1975, p. 219.

- Бондарюкф (Bondaryuk), Елена (Elena) (16 March 2018). "Дочь своего века, или Изменчивая Allegro" [The Daughter of Her Age, or the Volatile Allegro]. Крымский ТелеграфЪ (in Russian) (471). Simferopol, Crimea. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Kornblatt 2009, pp. 12, 22.

- Lossky 1951.

- Valliere 2007, p. 35.

- Vladimir Sergeyevich Solovyov, Russia and the Universal Church, trans. William G. von Peters (Chattanooga, TN: Catholic Resources, 2013).

- Vladimir Sergeyevich Solovyov, The Russian Church and the Papacy: An Abridgment of Russia and the Universal Church, ed. Ray Ryland (San Diego: Catholic Answers, 2001).

- Ryland, Ray (2003). "Soloviev's Amen: A Russian Orthodox Argument for the Papacy". Crisis. Vol. 21 no. 10. pp. 35–38. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- Solovyov, Vladimir. The Burning Bush: Writings on Jews and Judaism. Translated by Gregory Yuri Glazov. University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 978-0-268-02989-0.

- "SOLOVYEV, VLADIMIR SERGEYEVICH". The Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- Kornblatt 2009, pp. 68,174.

- Eskridge-Kosmach 2014, p. 662.

- Kornblatt 2009, pp. 24.

- Solovyov 2008.

- Cioran 1977, p. 71.

- Masaryk, Tomáš Garrigue. (1919). The Spirit of Russia: Studies in History, Literature and Philosophy, Volume 2. Allen & Unwin. p. 228

- Zouboff, Peter, Solovyov on Godmanhood: Solovyov's Lectures on Godmanhood Harmon Printing House: Poughkeepsie, New York, 1944; see Milosz 1990.

- Jacobs 2001, p. 44.

- "Nuclear Blast USA". www.nuclearblast.com. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- Carlson 1996.

- Powell 2007, p. 70.

- "SOPHIAN HERESY". ecumenizm.tripod.com. Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- Kostalevsky 1997.

- Lossky 1951, pp. 81–134.

- Zouboff, Peter P. (1944). Vladimir Solovyev's Lectures on Godmanhood. International University Press. p. 14. "The passionate intensity of his mental work shattered his health. On the thirty-first of July, in "Uzkoye", the country residence of Prince P. N. Troubetskoy, near Moscow, he passed away in the arms of his close friend, Prince S. N. Troubetskoy."

- Oberländer, Erwin; Katkov, George. (1971). Russia Enters the Twentieth Century, 1894-1917. Schocken Books. p. 248. ISBN 978-0805234046 "Vladimir Solovyev died in the arms of his friend Sergey Nikolayevich Trubetskoy (1862–1905), on the estate of Uzkoye."

- Solovyov, Vladimir (1948). Russia and the Universal Church. Translated by Herbert Rees. Geoffrey Bles Ltd. p. 10.

Works cited

- Carlson, Maria (1996). "Gnostic Elements in the Cosmogony of Vladimir Soloviev". In Kornblatt, Judith Deutsch; Gustafson, Richard F. (eds.). Russian Religious Thought. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 49–67. ISBN 978-0-299-15134-8.

- Cioran, Samuel (1977). Vladimir Solov'ev and the Knighthood of the Divine Sophia. Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

- Dahm, Helmut (1975). Vladimir Solovyev and Max Scheler: Attempt at a Comparative Interpretation. Sovietica. 34. Translated by Wright, Kathleen. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer. ISBN 978-90-277-0507-5.

- Eskridge-Kosmach, Alena (2014). "Russian Press and the Ideas of Russia's 'Special Mission in the East' and 'Yellow Peril'". Journal of Slavic Military Studies. 27 (4): 661–675. doi:10.1080/13518046.2014.963440. ISSN 1556-3006. S2CID 144102416.

- Jacobs, Alan (2001). "Bakhtin and the Hermeneutics of Love". In Felch, Susan M.; Contino, Paul J. (eds.). Bakhtin and Religion. Rethinking Theory. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press. pp. 25–46. ISBN 978-0-8101-1825-6.

- Kornblatt, Judith Deutsch (2009). Divine Sophia: The Wisdom Writings of Vladimir Solovyov. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-7479-8.

- Kostalevsky, Marina (1997). Dostoevsky and Soloviev: The Art of Integral Vision. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06096-6.

- Lossky, N. O. (1951). History of Russian Philosophy. New York: International Universities Press (published 1970). ISBN 978-0-8236-8074-0.

- Milosz, Czeslaw (1990). Introduction. War, Progress and the End of History: Three Conversations, Including a Short Story of the Anti-Christ. By Solovyov, Vladimir. Hudson, New York: Lindisfarne Press. ISBN 978-1-58420-212-7.

- Powell, Robert (2007) [2001]. The Sophia Teachings: The Emergence of the Divine Feminine in Our Time. Great Barrington, Massachusetts: Lindisfarne Books. ISBN 978-1-58420-048-2.

- Solovyov, Vladimir (2008). Jakim, Boris (ed.). The Religious Poetry of Vladimir Solovyov. Translated by Jakim, Boris; Magnus, Laury. San Rafael, California: Semantron Press. ISBN 978-1-59731-279-0.

- Valliere, Paul (2007). "Vladimir Soloviev (1853–1900)". In Witte, John, Jr.; Alexander, Frank S. (eds.). The Teachings of Modern Orthodox Christianity on Law, Politics, and Human Nature. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14264-9.

Further reading

- du Quenoy, Paul. "Vladimir Solov’ev in Egypt: The Origins of the ‘Divine Sophia’ in Russian Religious Philosophy," Revolutionary Russia, 23: 2, December 2010.

- Finlan, Stephen. "The Comedy of Divinization in Soloviev," Theosis: Deification in Christian Theology (Eugene, Or.: Wipf & Stock, 2006), pp. 168–183.

- Gerrard, Thomas J. "Vladimir Soloviev – The Russian Newman," The Catholic World, Vol. CV, April/September, 1917.

- Groberg, Kristi. "Vladimir Sergeevich Solov'ev: a Bibliography," Modern Greek Studies Yearbook, vol.14–15, 1998.

- Kornblatt, Judith Deutsch. "Vladimir Sergeevich Solov’ev," Dictionary of Literary Bibliography, v295 (2004), pp. 377–386.

- Mrówczyński-Van Allen, Artur. Between the Icon and the idol. The Human Person and the Modern State in Russian Literature and Thought - Chaadayev, Soloviev, Grossman (Cascade Books, /Theopolitical Visions/, Eugene, Or., 2013).

- Nemeth, Thomas. The Early Solov'ëv and His Quest for Metaphysics. Springer, 2014. ISBN 978-3-319-01347-3 [Print]; ISBN 978-3-319-01348-0 [eBook]

- Stremooukhoff, Dimitrii N. Vladimir Soloviev and his Messianic Work (Paris, 1935; English translation: Belmont, MA: Nordland, 1980).

- Sutton, Jonathan. The Religious Philosophy of Vladimir Solovyov: Towards a Reassessment (Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan, 1988).

- Zernov, Nicholas. Three Russian prophets (London: SCM Press, 1944).

External links

- Works by or about Vladimir Solovyov at Internet Archive

- Works by Vladimir Solovyov at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Vladimir Solovyov (1853–1900) – entry on Solovyov at Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- http://www.orthodoxphotos.com/readings/end/antichrist.shtml

- ALEXANDER II AND HIS TIMES: A Narrative History of Russia in the Age of Alexander II, Tolstoy, and Dostoevsky Several chapters on Solovyov

- http://www.utm.edu/research/iep/s/solovyov.htm

- http://www.christendom-awake.org/pages/soloviev/soloviev.html

- http://www.christendom-awake.org/pages/soloviev/biffi.html (address by Cardinal Giacomo Biffi)

- Vladimir-Sergeyevich-Solovyov // Britannica

- http://www.valley.net/~transnat/solsoc.html

- Tale of the Anti-Christ at the Wayback Machine (archived January 12, 2006) – excerpt from Three Conversations by Solovyov

- Civil Society and National Religion: Problems of Church, State, and Society in the Philosophy of Vladimir Solov'ëv (1853–1900) – research project at Centre for Russian Humanities Studies, Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen

- http://rumkatkilise.org/necplus.htm

- English translations of 5 poems, including 8 of 18 acrostics from the cycle "Sappho"

- English translations of 2 poems by Babette Deutsch and Avrahm Yarmolinsky, 1921

- "The Positive Unity: How Solovyov’s Ethics Can Contribute to Constructing a Working Model for Business Ethics in Modern Russia" by Andrey V. Shirin