Karl Rahner

Karl Rahner, SJ (5 March 1904 – 30 March 1984) was a German Jesuit priest and theologian who, alongside Henri de Lubac, Hans Urs von Balthasar, and Yves Congar, is considered to be one of the most influential Roman Catholic theologians of the 20th century. He was the brother of Hugo Rahner, also a Jesuit scholar.

Karl Rahner | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Rahner by L. M. Cremer | |

| Born | 5 March 1904 |

| Died | 30 March 1984 (aged 80) |

| Alma mater | |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Transcendental Thomism |

Main interests | |

Notable ideas | Anonymous Christian |

Influenced

| |

Rahner was born in Freiburg, at the time a part of the Grand Duchy of Baden, a state of the German Empire; he died in Innsbruck, Austria.

Before the Second Vatican Council, Rahner had worked alongside Congar, de Lubac, and Marie-Dominique Chenu, theologians associated with an emerging school of thought called the Nouvelle Théologie, elements of which had been condemned in the encyclical Humani generis of Pope Pius XII. Subsequently, however, the Second Vatican Council was much influenced by his theology and his understanding of Catholic faith.[2]

Biography

Karl Rahner's parents, Karl and Luise (Trescher) Rahner, had seven children, of whom Karl was the fourth. His father was a professor in a local college and his mother had a profound religious personality, which influenced the home atmosphere. Karl attended primary and secondary school in Freiburg, entering the Society of Jesus upon graduation; he began his Jesuit formation in the North German Province of the Jesuits in 1922, four years after his older brother Hugo entered the same order. Deeply affected by the spirituality of Ignatius of Loyola during the initial phase of his formation (1922–24), he concentrated the next phase of his formation (1924–7) on Catholic scholastic philosophy and the modern German philosophers: he seems to have been particularly interested in Immanuel Kant and two contemporary Thomists, the Belgian Jesuit Joseph Maréchal and the French Jesuit Pierre Rousselot, who were to influence Rahner's understanding of Thomas Aquinas in his later writings.[lower-alpha 1]

As a part of his Jesuit training, Rahner taught Latin to novices at Feldkirch (1927–29), then began his theological studies at the Jesuit theologate in Valkenburg aan de Geul in 1929. This allowed him to develop a thorough understanding of patristic theology, also developing interests in spiritual theology, mysticism, and the history of piety. Rahner was ordained a priest on 26 July 1932, and then made his final year of tertianship, the study and taking of Ignatius' Spiritual Exercises, at St. Andrä in Austria's Lavanttal Valley.[4]

Because Rahner's superiors wished him to teach philosophy at Pullach, he returned home to Freiburg in 1934 to study for a doctorate in philosophy, delving more deeply into the philosophy of Kant and Maréchal, and attended seminars by Martin Heidegger. His philosophy dissertation Geist in Welt, an interpretation of Aquinas's epistemology influenced by the transcendental Thomism of Maréchal and the existentialism of Heidegger,[lower-alpha 2] was ultimately rejected by his mentor Martin Honecker, allegedly for its bias toward Heidegger's philosophy and not sufficiently expressing the Catholic neo-scholastic tradition.[lower-alpha 3] In 1936 Rahner was sent to Innsbruck to continue his theological studies and there he completed his habilitationsschrift.[lower-alpha 4] Soon after he was appointed a Privatdozent (lecturer) in the faculty of theology of the University of Innsbruck, in July 1937. In 1939 the Nazis took over the University and Rahner, while staying in Austria, was invited to Vienna to work in the Pastoral Institute, where he both taught and became active in pastoral work until 1949. He then returned to the theology faculty at Innsbruck and taught on a variety of topics which later became the essays published in Schriften zur Theologie (Theological Investigations): the collection is not a systematic presentation of Rahner's views, but, rather a diverse series of essays on theological matters characterised by his probing, questioning search for truth.[6]

In early 1962, with no prior warning, Rahner's superiors in the Society of Jesus told him that he was under Rome's pre-censorship, which meant that he could not publish or lecture without advance permission. The objections of the Roman authorities focused mainly on Rahner's views on the Eucharist and Mariology, however the practical import of the pre-censorship decision was voided in November 1962 when, without any objection, John XXIII appointed Rahner a peritus (expert advisor) to the Second Vatican Council: Rahner had complete access to the council and numerous opportunities to share his thought with the participants. Rahner's influence at Vatican II was thus widespread, and he was subsequently chosen as one of seven theologians who would develop Lumen gentium, the dogmatic explication of the doctrine of the Church.[lower-alpha 5][8] The council's receptiveness towards other religious traditions may be linked to Rahner's notions of the renovation of the church, God's universal salvific revelation, and his desire to support and encourage the ecumenical movement.[lower-alpha 6]

During the council, Rahner accepted the Chair for Christianity and the Philosophy of Religion at the University of Munich and taught there from 1964 to 1967. Subsequently, he was appointed to a chair in dogmatic theology at the Catholic theological faculty of the University of Münster, where he stayed until his retirement in 1971.[10] Rahner then moved to Munich and in 1981 to Innsbruck, where he remained for the next 3 years as an active writer and lecturer, also continuing his active pastoral ministry. He published several volumes (23 total in English) of collected essays for the Schriften zur Theologie (Theological Investigations), expanded the Kleines theologisches Wörterbuch (Theological Dictionary), co-authored other texts such as Unity of the Churches: An Actual Possibility with Heinrich Fries, and in 1976 he completed the long-promised systematic work, Foundations of Christian Faith.[11][lower-alpha 7]

Rahner fell ill from exhaustion and died on 30 March 1984 at the age of 80, after a birthday celebration that also honoured his scholarship. He was buried at the Jesuit Church of the Holy Trinity in Innsbruck.[12] During his years of philosophical and theological study and teaching, Rahner produced some 4,000 written works.[13]

Work

Rahner's output is extraordinarily voluminous. In addition to the above-mentioned writings, his other major works include: the ten-volume encyclopaedia, Lexicon für Theologie und Kirche; a six-volume theological encyclopaedia, Sacramentum Mundi, and many other books, essays, and articles.[lower-alpha 8] In addition to his own work, the reference texts that Rahner edited also added significantly to the general impact of his own theological views.

The basis for Rahner's theology is that all human beings have a latent ("unthematic") experience of God in any perception of meaning or "transcendental experience". It is only because of this proto-revelation that recognising a distinctively special revelation (such as the Christian Gospel) is possible.[14] His theology influenced the Second Vatican Council and was ground-breaking for the development of what is generally seen as the modern understanding of Catholicism. A popular anecdote, that resonates with those who find some of Karl Rahner's works difficult reading, comes from his brother Hugo who quipped that in his retirement he'd try to translate his brother's works ... into German![15]

Foundations of Christian Faith

Written near the end of his life, Rahner's Foundations of Christian Faith (Grundkurs des Glaubens) is the most developed and systematic of his works, most of which were published in the form of essays.

Economic and immanent Trinity

Among the most important of his essays was The Trinity, in which he argues that "the economic Trinity is the immanent Trinity, and the immanent Trinity is the economic Trinity". That is to say, God communicates Himself to humanity ("economic" Trinity) as He really is in the divine Life ("immanent" Trinity).

Rahner was emphatic that the identity between "economic" Trinity and "immanent" Trinity does not lead to Modalism, because God could not communicate Himself to humanity as threefold (dreifaltige) unless He were threefold in reality. Nonetheless, some theologians and Christian philosophers (e.g., Jürgen Moltmann) have found his teaching to tend strongly in a Modalist direction.[16]

God's self-communication

Rahner maintained that the fulfillment of human existence consists in receiving God's self-communication, and that the human being is actually constituted by this divine self-communication.

Transfinalization

Rahner was a critic of substance theory and was concerned about the finality of liturgy. He proposed instead to rename transubstantiation into transfinalization. However, this theory was condemned by Pope Paul VI in the encyclical Mysterium fidei.[17][18]

Awareness of God

The basis for Rahner's theology is that all human beings have a latent ("unthematic") awareness of God in any experiences of limitation in knowledge or freedom as finite subjects. Because such experience is the "condition of possibility" for knowledge and freedom as such, Rahner borrows the language of Kant to describe this experience as "transcendental".[4][6] This transcendental experiential factor reveals his closeness to Maréchal's transcendental Thomism.[19]

Such is the extent of Rahner's idea of the "natural knowledge of God"—what can be known by reason prior to the advent of "special" revelation—that God is only approached asymptotically, in the mode of what Rahner calls "absolute mystery". While one may try to furnish proofs for God's existence, these explicit proofs ultimately refer to the inescapable orientation towards Mystery which constitute—by transcendental necessity—the very nature of the human being.

God as Absolute Mystery

Rahner often prefers the term "mystery" to that of "God".[20] He identifies the God of Absolute Being as Absolute Mystery.[21] At best, philosophy approaches God only asymptotically, evoking the question whether attempts to know God are in vain. Can the line between the human asymptote and the Mystery asymptote connect?[22]

In Rahner's theology, the Absolute Mystery reveals himself in self-communication.[23] Revelation, however, does not resolve the Mystery; it increases cognizance of God's incomprehensibility.[24] Experiences of the mystery of themselves point people to the Absolute Mystery, "an always-ever-greater Mystery."[25] Even in heaven, God will still be an incomprehensible mystery.[24]

Homanisation and Incarnation

Rahner examines evolution in his work Homanisation (1958, rev. 1965). The title represents a term he coined, deriving it from "hominization", the theory of man's evolutionary origins. The book's Preface describes the limits of Catholic theology with respect to evolution, further on giving a summary of official church teaching on the theory. He then continues in the next sections to propound "fundamental theology" in order to elucidate the background or foundation of church teaching. In the third section he raises some philosophical and theological questions relating to the concept of becoming, the concept of cause, the distinction between spirit and matter, the unity of spirit and matter, the concept of operation, and the creation of the spiritual soul.[19] In his writing, Rahner does not simply deal with the origin of man but with his existence and his future, issues that can be of some concern to evolutionary theory. Central for Rahner is the theological doctrine of grace, which for Rahner is a constituent element of man's existence, so that grace is a permanent modification of human nature in a supernatural "existential", to use a Heidegger term. Accordingly, Rahner doubts the real possibility of a state of pure nature (natura pura), which is human existence without being involved with grace. In treating the present existence of man and his future as human, Rahner affirms that "the fulfillment of human existence occurs in receiving God's gift of Himself, not only in the beatific vision at the end of time, but present now as seed in grace.[26]

Multiple Incarnations

Rahner has been open to the prospect of extraterrestrial intelligence, the idea that cosmic evolution has yielded sentient life forms in other galaxies. Logically, this raises for Rahner some important questions of philosophical, ethical, and theological significance: he argues against any theological prohibition of the notion of extraterrestrial life, while separating the existential significance of such life forms from that of angels. Moreover, Rahner advances the possibility of multiple Incarnations, but does not delve into it: given the strong Christological orientation of his theology, it does not appear likely he would have propended for repetitions of the Incarnation of Christ.[26]

Incarnation-grace

For Rahner, at the heart of Christian doctrine is the co-reality of Incarnation-grace. Incarnation and grace appear as technical terms to describe the central message of the Gospel: God has communicated Himself. The self-communication of God is crucial in Rahner's view: grace is not something other than God, not some celestial 'substance,' but God Himself. The event of Jesus Christ is, according to Rahner, the centre-point of the self-communication of God. God, insists Rahner, does not only communicate Himself from without; rather, grace is the constitutive element both of the objective reality of revelation (the incarnate Word) and the subjective principle of our hearing (the internal Word and the Holy Spirit). To capture the relation between these aspects of grace, Rahner appropriates the Heideggerian terminology of "thematization:" the objective mediation is the explicit "thematization" of what is always already subjectively proffered — the history of grace's categorical expression without, culminating in the event of Jesus Christ, is the manifestation of what is always already on offer through the supernatural existential, which enters amid a transcendental horizon within.[27]

Mode of grace

Rahner's particular interpretation of the mode in which grace makes itself present is that grace is a permanent modification of human nature in a supernatural existential (a phrase borrowed from Heidegger). Grace is perceived in light of Christianity as a constitutive element of human existence. For this reason, Rahner denies the possibility of a state of pure nature (natura pura, human existence without being-involved with grace), which according to him is a counterfactual.

Language about God: univocity and equivocation

Like others of his generation, Rahner was much concerned with refuting the propositional approach to theology typical of the Counter-Reformation. The alternative he proposes is one where statements about God are always referring back to the original experience of God in mystery. In this sense, language regarding being is analogically predicated of the mystery, inasmuch as the mystery is always present but not in the same way as any determinate possible object of consciousness.[28][29] Rahner would claim Thomas Aquinas as the most important influence on his thought, but also spoke highly of Heidegger as "my teacher", and in his elder years Heidegger used to visit Rahner regularly in Freiburg.[30]

Some have noted that the analogy of being is greatly diminished in Rahner's thought. Instead, they claim, equivocal predication dominates much of Rahner's language about God. In this respect, similarity between him and other Thomist-inspired theologians is seen as problematic. Others, however, identify Rahner's primary influence not in Heidegger but in the Neo-Thomists of the early 20th century, especially the writings of Joseph Maréchal.[14]

Criticism of Jesusism

Rahner criticised Jesusism, despite his stated respect for the position. Jesusism tends to focus narrowly on Jesus' life for imitation, apart from the Christian God or Church.[31]

Christology

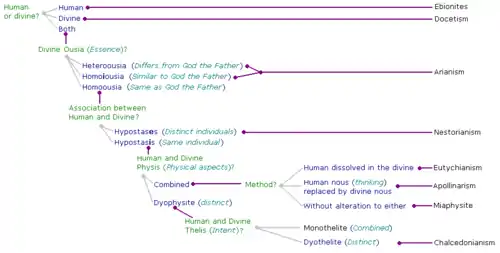

If the task of Christology is to make intelligible the Christian faith that Jesus of Nazareth, a historical person, is Christ as the centre of all human history and the final and full revelation of God to humanity—then Rahner feels that within "the contemporary mentality which sees the world from an evolutionary point of view"[32] the person of Christ should not be emphasised in his unique individuality whilst ignoring any possibility of combining the event of Christ with the process of human history as a whole. In fact, it appears there are some limitations of classic Christological formula suggested by the Council of Chalcedon (AD 451) which affirms "one identical Son, our Lord Jesus Christ ... perfect both in his divinity and in his humanity ... [with] two natures without any commingling or change or division or separation ... united in one person."[33] Moreover, the Chalcedon formula adopts philosophical concepts such as nature and hypostatic union which are no longer used to explain and interpret religious experiences.[34]

Thus, Rahner introduces transcendental Christology, which interprets the event and person of Christ in relation to the essential structure of the human person, reflecting on the essential conditions of all human experiences, conditions which transcend any one particular kind of experience.[35] One should however first look into Rahner's basic insights on Christology within an evolutionary view of the world, which claims that Christian faith sees all things in the world come from the one same origin, God. This means that in spite of their differences, there is "an inner similarity and commonality" among things, which forms a single world. This commonality is most clearly disclosed in a human being as a form of the unity of spirit and matter: it is only in a human person that spirit and matter can be experienced in their real essence and in their unity. Rahner states that spirit represents the unique mode of existence of a single person when that person becomes self-conscious and is always oriented towards the incomprehensible Mystery called God. However, it is only in the free acceptance by the subject of this mystery and in its unpredictable disposal of the subject that the person can genuinely undertake this process of returning to the self. Conversely, matter is the condition which makes human beings estranged from themselves towards other objects in the world and makes possible an immediate intercommunication with other spiritual creatures in time and space. Even if there is an essential difference between spirit and matter, that is not understood as an essential opposition: the relationship between the two can be said as "the intrinsic nature of matter to develop towards spirit".[36] This kind of becoming from matter to spirit can be called self-transcendence which "can be only understood as taking place by the power of the absolute fullness of being":[37] the evolutionary view of the world allows us to consider that humanity is nothing but the latest stage of the self-transcendence of matter.[38]

Christian faith and God's self-communication

According to Rahner, Christian faith affirms that the cosmos reaches its final fulfillment when it receives the immediate self-communication of its own ground in the spiritual creatures which are its goal and its high point.[39] Rahner further states that God's self-communication to the world is the final goal of the world and that the process of self-transcendence makes the world already directed towards this self-communication and its acceptance by the world.[40] As a consequence, and explaining the place of Christ in this whole process of self-transcendence of the world, Rahner says that it has to do with the process of the intercommunication of spiritual subjects, because otherwise there is no way to retain the unity of the very process. God's self-communication is given to cosmic subjects who have freedom to accept or reject it and who have intercommunication with other existents. It takes place only if the subjects freely accept it, and only then forms a common history in a sense that "it is addressed to all men in their intercommunication" then "addressed to others as a call to their freedom".[41] In this sense, Rahner claims that "God's self-communication must have a permanent beginning and in this beginning a guarantee that it has taken place, a guarantee by which it can rightly demand a free decision to accept this divine self-communication".[41] Within this scheme, the saviour refers to a historical person "who signifies the beginning of the absolute self-communication of God which is moving towards its goal, that beginning which indicates that this self-communication for everyone has taken place irrevocably and has been victoriously inaugurated".[41] Hypostatic union, therefore, happens in an intrinsic moment when God's self-communication and its acceptance by that person are met, and this union is open to all spiritual creatures with the bestowal of grace. In order to be fulfilled, this event should have "a concrete tangibility in history".[42]

Transcendental Christology and mediation

If one then examines Rahner's transcendental Christology, it may be seen that it "presupposes an understanding of the relationship of mutual conditioning and mediation in human existence between what is transcendentally necessary and what is concretely and contingently historical".[43] It is a sort of relationship between the two elements in such a way that "the transcendental element is always an intrinsic condition of the historical element in the historical self" while "in spite of its being freely posited, the historical element co-determines existence in an absolute sense".[43] Transcendental Christology is "the experiences which man always and inescapably has".[43] Human beings were created to freely transcend themselves and the objects in the world, towards the incomprehensible Mystery called God; the limitations of human situation make a human being hope that the full meaning of humanity and the unity of everything in the world will be fulfilled by God's self-giving. Furthermore, God's self-communication and human hope for it should be "mediated historically" because of "the unity of transcendentality and historicity in human existence": human hope looks in history for its salvation from God that "becomes final and irreversible, and is the end in an 'eschatological' sense".[44] At this point Rahner proposes two possibilities of human salvation, i.e. either as "fulfillment in an absolute sense" which means the establishment of the Kingdom of God on earth, or as "a historical event within history".[45] The event of human salvation by God's self-giving love should be the event of a human person, because God's salvific love can only be effective in history when a person freely accepts his love, surrenders everything to God in death, and in death is accepted by God.[45] Rahner significantly affirms that the character of the saviour is exemplary and absolute: given the unity of the world and of history from the view point of both God and the world, such an "individual" destiny has "exemplary" significance for the world as a whole. Such a man with this destiny is what is meant by an "absolute saviour".[45]

Saviour and hypostatic union

Rahner believes that the saviour described by his transcendental Christology is not diverse from the one presented by the classic Christological formulations of Chalcedon, which used a concept of hypostatic union to claim Jesus as the Christ. Accordingly, he then proceeds to articulate the meaning of the hypostatic union.[46] The issue is how to understand the meaning of "human being": Rahner understands the phrase “became man” as assuming an individual human nature as God's own, and emphasises "the self-emptying of God, his becoming, the kenosis and genesis of God himself".[47] God "assumes by creating" and also "creates by assuming", that is, he creates by emptying himself, and therefore, of course, he himself is in the emptying. He creates the human reality by the very fact that he assumes it as his own.[47] God's creating-by-emptying act belongs to God's power and freedom as the absolute One and to God's self-giving love expressed in scripture.[47] Therefore, it is legitimate for Rahner to assert that God "who is not subject to change in himself can himself be subject to change in something else". This is what the doctrine of the Incarnation teaches us: "in and in spite of his immutability he can truly become something: he himself, he in time".[48]

According to Rahner, human beings are created to be oriented towards the incomprehensible Mystery called God. However, this human orientation towards the Mystery can be fully grasped only if we as humans freely choose to be grasped by the incomprehensible One: if God assumes human nature as God's own reality with God's irrevocable offer of God's self-communication, and a person freely accepts it, the person is united with God, reaching the very point towards which humanity is always moving by virtue of its essence, a God-Man which is fully fulfilled in the person of Jesus of Nazareth claimed by Christian faith. In this sense, Rahner sees the incarnation of God as "the unique and highest instance of the actualization of the essence of human reality".[49]

God-Man in history

To answer the question of how we find a God-Man in history, Rahner employs a historical approach to Christology by examining the history of the life and death of Jesus of Nazareth and proposes two theses beforehand: 1) Christian faith requires a historical basis; and 2) considering a possibility of significant difference between who the person is and the extent to which that person verbalises or expresses identity, it is possible both to say that "the self-understanding of the pre-resurrection Jesus may not contradict in an historical sense the Christian understanding of his person and his salvific significance", and to state that his self-understanding may not coincide with the content of Christological faith.[50]

To establish the grounds of Christian faith, Rahner asserts that two points should be proven as historically credible—first, that Jesus saw himself "as the eschatological prophet, as the absolute and definitive saviour", and second, that the resurrection of Jesus is the absolute self-communication of God.[51] There are several historical elements concerning Jesus' identity as a Jew and "radical reformer": his drastic behaviour in solidarity with social and religious outcasts based on his belief in God, his essential preaching "as a call to conversion", his gathering disciples, his hope for conversions of others, his acceptance of death on the cross "as the inevitable consequence of fidelity to his mission".[52]

Death and resurrection

Rahner states that the death and the resurrection of Jesus are two aspects of a single event not to be separated,[53] even though the resurrection is not a historical event in time and place like the death of Jesus. What the Scripture offers are powerful encounters in which the disciples come to experience the spirit of the risen Lord Jesus among them, provoking a resurrection faith of the disciples as "a unique fact".[54] The resurrection is not a return to life in the temporal sphere, but the seal of God the Father upon all that Jesus stood for and preached in his pre-Easter life. "By the resurrection... Jesus is vindicated as the absolute saviour" by God:[55] it means "this death as entered into in free obedience and as surrendering life completely to God, reaches fulfillment and becomes historically tangible for us only in the resurrection".[56] Thus, in the resurrection, the life and death of Jesus are understood as "the cause of God's salvific will" and open the door to our salvation: "we are saved because this man who is one of us has been saved by God, and God has thereby made his salvific will present in the world historically, really and irrevocably".[56] In this sense, Jesus of Nazareth becomes a God-Man, the absolute saviour.

Anonymous Christianity

Anonymous Christianity is the theological concept that declares that people who have never heard the Christian Gospel might be saved through Christ.

Inspiration for this idea sometimes comes from the Second Vatican Council's Lumen gentium, which teaches that those "who through no fault of their own do not know the Gospel of Christ or His Church, but who nevertheless seek God with a sincere heart, and moved by grace, try in their actions to do His will as they know it through the dictates of their conscience—those too may achieve eternal salvation".[57]

Rahner's development of the idea preceded the council, and became more insistent after it received its conciliar formulation. Non-Christians could have "in [their] basic orientation and fundamental decision", Rahner wrote, "accepted the salvific grace of God, through Christ, although [they] may never have heard of the Christian revelation."[58] His writings on the subject were somewhat related to his views about the mode of grace.[59]

Non-Christian religions

Rahner's transcendental Christology opens another horizon which comprises non-Christian religions, as God's universal saving will in Christ extends to non-Christians: since Christ is the saviour of all people, salvation for non-Christians comes only through Christ (anonymous Christians). Just as importantly, it is possible to say that Christians can learn from other religions or atheistic humanism because God's grace is and can be operative in them.[60] The presence of Christ in other religions operates in and through his Spirit[61] and non-Christians respond to the grace of God through "the unreflexive and 'searching Christology'" (searching "memory" of the absolute saviour) present in the hearts of all persons.[62] Three specific attitudes become involved: 1) an absolute love towards one's neighbours; 2) an attitude of readiness for death; and 3) an attitude of hope for the future.[63] In practising these, the person is acting from and responding to the grace of God that was fully manifest in the life of Jesus.[4]

Selected bibliography

A complete bibliography is available at

- 1954–1984. Schriften zur Theologie. 16 volumes. Einsiedeln: Benziger Verlag.

- 1965. Homanisation. Translated by W. J. O’Hara. West Germany: Herder K.G.

- 1968. Spirit in the World. Revised edition by J. B. Metz. Translated by William V. Dych. (Translation of Geist im Welt: Zur Metaphisik der endlichen Erkenntnis bei Thomas von Aquin. Innsbruck: Verlag Felizian Rauch, 1939; 2nd ed. Revised by J. B. Metz. München: Kösel-Verlag, 1957) New York: Herder and Herder.

- 1969. Hearers of the Word. Revised edition by J. B. Metz. Translated by Michael Richards. (Translation of Hörer des Wortes: Zur Grundlegung einer Religionsphilosophie. München: Verlag Kösel-Pustet, 1941) New York: Herder and Herder.

- 1970. The Trinity. Translated by Joseph Donceel. New York: Herder and Herder.

- 1978, 1987. Foundations of Christian Faith: An Introduction to the Idea of Christianity. Translated by William V. Dych. (Translation of Grundkurs des Glaubens: Einführung in den Begriff des Christentums. Freiburg: Verlag Herder, 1976) New York: The Seabury Press; New York: Crossroad.

- 1985. I Remember. New York: Crossroad.

- 1990. Faith in a Wintry Season: Conversations and Interviews With Karl Rahner in the Last Years of His Life, with Paul Imhof & Hubert Biallowons, eds. New York: Crossroad.

- 1993. Content of Faith: The Best of Karl Rahner Theological Writings. New York: Crossroad.

See also

Notes

- As well as offering Rahner a way to deal with Kant's transcendental method in relation to Thomistic epistemology, Maréchal and Rousselot, as Rahner himself later mentioned, deeply influenced his own philosophical and theological work. Maréchal was famous for his study on Kant and Thomism, especially for applying Kant's transcendental method to Thomistic epistemology.[3]

- That is, the relation between Aquinas's notion of dynamic mind and Heidegger's analysis of Dasein, or "being-in-the-world".

- According to Herbert Vorgrimler, Honecker's rejection of Rahner's dissertation reflected the former's dislike of Heidegger's philosophy. Thirty four years later the Philosophical Faculty of the University of Innsbruck gave Rahner an honorary doctorate for his philosophical works, especially for his failed dissertation, published in 1939 as Geist in Welt (Spirit in World). At any rate, it was in the early 1930s that Rahner elucidated his conviction that the human search for meaning was rooted in the unlimited horizon of God's own being experienced within the world.[5]

- A second dissertation qualifying one to teach at university level. The English title of this dissertation was From the Side of Christ: The Origin of the Church as Second Eve from the Side of Christ the Second Adam. An Examination of the Typological Meaning of John 19:34.

- Rahner had input to many of the other conciliar presentations as well.[7]

- According to Herbert Vorgrimler, it is not hard to trace Rahner's influence on the work of the council (apart from four texts: the Decree On the Means of Social Communication, the Decree On the Catholic Eastern Churches, the Declaration on Christian education, and the Declaration on Religious Liberty).[9]

- For specific biographical information, see Michaud n.d.

- For a complete bibliography, see list at .

References

- Carbine & Koster 2015, p. xxix.

- Declan Marmion (1 March 2017). "Karl Rahner, Vatican II, and the Shape of the Church". Theological Studies. 78 (1): 25–48. doi:10.1177/0040563916681992. ISSN 0040-5639. S2CID 171510292.

- Vorgrimler 1986, p. 51.

- Michaud n.d.

- Vorgrimler 1986, p. 62.

- Masson, Robert (5 January 2013). "Karl Rahner: A Brief Biography". Karl Rahner Society. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Vorgrimler 1986, pp. 100–102.

- Second Vatican Council 1964.

- Vorgrimler 1986, p. 100.

- "Chronology". Karl Rahner Society. 5 January 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Rahner, Karl (1 July 1979). "Foundations of Christian Faith: An Introduction to the Idea of Christianity". Religious Studies Review. 5 (3): 190–199. doi:10.1111/j.1748-0922.1979.tb00215.x. ISSN 1748-0922.

- Byers & Bourgoin 2004.

- Kennedy 2010, p. 134.

- "Karl Rahner (Boston Collaborative Encyclopedia of Western Theology)". people.bu.edu. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- Marika (19 March 2010). "Theologies: Karl Rahner on Theology and Anthropology". Theologies. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- Moltmann 1993, p. 144.

- Hardon, John A. (1998). "Defending the Faith". Lombard, Illinois: Real Presence Eucharistic Education and Adoration Association. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Paul VI 1965.

- Mulvihill 2009.

- Mawhinney 1968.

- Ryan 2010, p. 44.

- Duffy 2005, p. 44.

- Duffy 2005, pp. 44–45.

- Dulles 2013.

- Petty 1996, p. 88; Steinmetz 2012, pp. 1, 3.

- Mulvihill 2009; Rahner 1965.

- Cf. Karl Rahner, Foundations of Christian Faith, (New York: Crossroad, 1978) 24-175.

- Maher, Anthony M. (1 December 2017). The Forgotten Jesuit of Catholic Modernism: George Tyrrell's Prophetic Theology, Chapter 9, section 1. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781506438511.

- Speidell, Todd (8 November 2016). Fully Human in Christ: The Incarnation as the End of Christian Ethics. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 88. ISBN 9781498296373.

- Sheehan, Thomas (4 February 1982). "The Dream of Karl Rahner". The New York Review of Books. ISSN 0028-7504. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- Linnane 2005, p. 166.

- Rahner 1978, p. 206.

- Hentz 1991, p. 110; see also O'Collins 2009, pp. 238–248.

- For the whole Christology section, refer to Michaud n.d.

- Rahner 1978, pp. 206–212.

- Rahner 1978, p. 184.

- Rahner 1978, p. 185.

- Hentz 1991; Michaud n.d.

- Rahner 1978, p. 190.

- Rahner 1978, p. 192.

- Rahner 1978, p. 193.

- Rahner 1978, p. 201.

- Rahner 1978, p. 208.

- Rahner 1978, pp. 210–211.

- Rahner 1978, p. 211.

- O'Collins 2009, pp. 217, 243.

- Rahner 1978, p. 222.

- Rahner 1978, pp. 220–223.

- Rahner 1978, p. 218.

- Rahner 1978, p. 236.

- Rahner 1978, pp. 245–246.

- Rahner 1978, pp. 247–264.

- Rahner 1978, p. 266.

- Rahner 1978, p. 274.

- Rahner 1978, p. 279.

- Rahner 1978, p. 284.

- "Lumen gentium, 16". www.vatican.va. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- D'Costa 1985, p. 132.

- Clinton 1998.

- Schineller 1991, p. 102.

- Rahner 1978, p. 316.

- Rahner 1978, pp. 295, 318.

- Rahner 1978, pp. 295–298.

Works cited

- Byers, Paula K.; Bourgoin, Suzanne M., eds. (2004). "Karl Rahner". Encyclopedia of World Biography. 13 (2nd ed.). Detroit, Michigan: Gale. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-7876-2553-5.

- Carbine, Rosemary P.; Koster, Hilda P. (2015). "Introduction: The Gift of Kathryn Tanner's Theological Imagination". In Carbine, Rosemary P.; Koster, Hilda P. (eds.). The Gift of Theology: The Contribution of Kathryn Tanner. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress Press. pp. xxv–xxxix. doi:10.2307/j.ctt155j3hm.6. ISBN 978-1-5064-0285-7.

- Clinton, Stephen M. (1998). Peter, Paul, and the Anonymous Christian: A Response to The Mission Theology of Rahner and Vatican II (PDF). Orlando, Florida: The Orlando Institute. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- D'Costa, Gavin (1985). "Karl Rahner's Anonymous Christian: A Reappraisal". Modern Theology. 1 (2): 131–148. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0025.1985.tb00013.x. ISSN 0266-7177.

- Duffy, Stephen J. (2005). "Experience of Grace". In Marmion, Declan; Hines, Mary E. (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Karl Rahner. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Dulles, Avery (2013). "Revelation". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- Hentz, Otto H. (1991). "Anticipating Jesus Christ: An Account of Our Hope". In O'Donovan, Leo J. (ed.). A World of Grace: An Introduction to the Themes and Foundations of Karl Rahner's Theology. New York: Crossroad.

- Kennedy, Philip (2010). Twentieth-Century Theologians: A New Introduction to Modern Christian Thought. I. B. Tauris.

- Linnane, Brian (2005). "Ethics". In Marmion, Declan; Hines, Mary E. (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Karl Rahner. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 158–173. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521832888.011. ISBN 978-0-521-54045-2.

- Mawhinney, John J. (1968). "The Concept of Mystery In Karl Rahner's Philosophical Theology". Union Seminary Quarterly Review. 24 (1): 17–30. ISSN 0362-1545.

- Michaud, Derek (n.d.). "Karl Rahner (1904–1984)". In Wildman, Wesley (ed.). Boston Collaborative Encyclopedia of Western Theology. Boston: Boston University. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Moltmann, Jürgen (1993) [1980]. The Trinity and the Kingdom: the Doctrine of God. Translated by Kohl, Margaret. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-2825-3.

- Mulvihill, John Edward (2009). "Neo-Scholastics in Germany". Philosophy of Evolution: Survey of Literature. Franklin Park, Illinois. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- O'Collins, Gerald (2009). Christology: A Biblical, Historical, and Systematic Study of Jesus. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Paul VI (1965). Mysterium fidei (encyclical letter). Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- Petty, Michael W. (1996). A Faith that Loves the Earth: The Ecological Theology of Karl Rahner. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America.

- Rahner, Karl (1965). Homanisation. Translated by O'Hara, W. J. West Germany: Herder K.G. Archived from the original on 21 June 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2017 – via Religion Online.

- ——— (1978). Foundations of Christian Faith: An Introduction to the Idea of Christianity. Translated by Dych, William V. New York: Seabury Press.

- Ryan, Fáinche (2010). "Rahner and Aquinas: The Incomprehensibility of God". In Conway, Pádraic; Ryan, Fáinche (eds.). Karl Rahner: Theologian for the Twenty-first Century. Studies in Theology, Society, and Culture. 3. Bern: Peter Lang. pp. 41–60. ISBN 978-3-03-430127-5. ISSN 1662-9930.

- Schineller, J. Peter (1991). "Discovering Jesus Christ: A History We Share". In O'Donovan, Leo J. (ed.). A World of Grace: An Introduction to the Themes and Foundations of Karl Rahner's Theology. New York: Crossroad.

- Second Vatican Council (1964). Lumen gentium. Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- Steinmetz, Mary (2012). "Thoughts on the Experience of God in the Theology of Karl Rahner: Gifts and Implications". Lumen et Vita. 2 (1). ISSN 2329-1087. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Vorgrimler, Herbert (1986). Understanding Karl Rahner: An Introduction to His Life and Thought. New York: Crossroad.

Further reading

- Burke, Patrick (2002). Reinterpreting Rahner: A Critical Study of His Major Themes. Fordham University Press.

- Carr, Anne (1977). The Theological Method of Karl Rahner. Scholars Press.

- Egan, Harvey J. (1998). Karl Rahner: Mystic of Everyday Life. Crossroad.

- Endean, Philip (2001). Karl Rahner and Ignatian Spirituality. Oxford.

- Fischer, Mark F. (2005). The Foundations of Karl Rahner. Crossroad.

- Hussey, M. Edmund (2012). The Idea of Christianity: A Brief Introduction to the Theology of Karl Rahner. ASIN B00A3DMVYM.

- Kelly, Geffrey B., ed. (1992). Karl Rahner: Theologian of the Graced Search for Meaning. Fortress Press.

- Kilby, Karen (2007). A Brief Introduction to Karl Rahner. Crossroad.

- Kress, Robert (1982). A Rahner Handbook. John Knox Press.

- Sheehan, Thomas (1987). Karl Rahner: The Philosophical Foundations. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press.

- Tillich, Paul (1950). Systematic Theology. Volume I: Reason and Revelation—Being and God. University of Chicago Press.

- Woodward, Guy (n.d.). "Karl Rahner (1904–1984)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. ISSN 2161-0002. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Karl Rahner |

- Karl Rahner Society with biography and bibliography

- Karl Rahner Archive in Munich

- Bibliographical aids

- Works by or about Karl Rahner in libraries (WorldCat catalog)