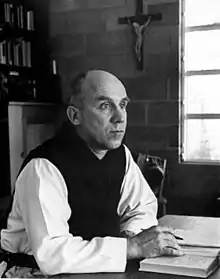

Thomas Merton

Thomas Merton OCSO (January 31, 1915 – December 10, 1968) was an American Trappist monk, writer, theologian, mystic, poet, social activist, and scholar of comparative religion. On May 26, 1949, he was ordained to the priesthood and given the name "Father Louis".[1][2] He was a member of the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani, near Bardstown, Kentucky, living there from 1941 to his death.

Thomas Merton | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 31, 1915 Prades, Pyrénées-Orientales, France |

| Died | December 10, 1968 (aged 53) Samut Prakan, Thailand |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation |

|

| Religion | Christianity (Roman Catholic) |

| Church | Latin Church |

| Ordained | 1949 |

| Writings | The Seven Storey Mountain (1948) |

| Part of a series on |

| Christian mysticism |

|---|

|

Merton wrote more than 50 books in a period of 27 years,[3] mostly on spirituality, social justice and a quiet pacifism, as well as scores of essays and reviews. Among Merton's most enduring works is his bestselling autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain (1948). His account of his spiritual journey inspired scores of World War II veterans, students, and teenagers to explore offerings of monasteries across the US.[4][5] It is among National Review's list of the 100 best non-fiction books of the century.[6]

Merton became a keen proponent of interfaith understanding, exploring Eastern religions through his study of mystic practice. He is particularly known for having pioneered dialogue with prominent Asian spiritual figures, including the Dalai Lama; Japanese writer D. T. Suzuki; Thai Buddhist monk Buddhadasa, and Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh. He traveled extensively in the course of meeting with them and attending international conferences on religion. In addition, he wrote books on Zen Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism, and how Christianity related to them. This was highly unusual at the time in the United States, particularly within the religious orders.

Biography

Early life

Thomas Merton was born in Prades, Pyrénées-Orientales, France, on January 31, 1915, to Owen Merton, a New Zealand painter active in Europe and the United States, and Ruth Jenkins, an American Quaker and artist. They had met at painting school in Paris.[7] He was baptized in the Church of England, in accordance with his father's wishes.[8] Merton's father was often absent during his son's childhood.

During World War I, in August 1915, the Merton family left France for the United States. They lived first with Ruth's parents in Queens, New York, and then settled near them in Douglaston. In 1917, the family moved into an old house in Flushing, Queens, where Merton's brother John Paul was born on November 2, 1918.[9] The family was considering returning to France when Ruth was diagnosed with stomach cancer. She died from it on October 21, 1921, in Bellevue Hospital. Merton was six years old and his brother not yet three.[10]

In 1922, his father took Thomas with him on a trip to Bermuda,[11] where Owen fell in love with American novelist Evelyn Scott. She was in a common-law marriage. Still grieving for his mother, Thomas never quite warmed to Scott.

Happy to get away from Scott, Thomas was returned to Douglaston in 1923 at the age of eight to live with his mother's family, who were also caring for his brother. Owen Merton, Scott, and her common-law husband, Frederick Creighton Wellman, sailed to Europe. They traveled through France, Italy, and England, and crossed the Mediterranean to Algeria. During the winter of 1924, while in Algeria, Owen Merton became ill and was thought to be near death.[12] By March 1925, He was well enough to organize a show of his paintings at the Leicester Galleries in London.

Owen returned to New York to pick up Thomas, bringing his son to live with his household in Saint-Antonin, France. Thomas returned to France with mixed feelings, as he had lived with his grandparents for the last two years and had become attached to them.[13] During their travels, Merton's father and Scott had sometimes discussed marriage. After returning to France, Owen realized that Thomas would not be reconciled to Scott, and broke off his relationship with her.[14]

France 1926

In 1926, when Merton was eleven, his father enrolled him in a boys' boarding school in Montauban, the Lycée Ingres. There, Merton felt lonely, depressed and abandoned. During his initial months at the school, Merton begged his father to remove him. With time, however, he grew comfortable with his surroundings. He befriended a circle of aspiring writers at the Lycée and he wrote two novels.[15]

On Sundays the Lycée arranged for the boys to attend a nearby Catholic Mass, but Merton never joined them. He often took an early train home to his father. A Protestant minister visited the Lycée on Sundays to serve students who did not attend Mass, but Merton took scant interest. During the Christmas breaks of 1926 and 1927, he spent his time with friends of his father in Murat, Auvergne.

He admired a devout Catholic couple, but they only discussed religion once. Merton expressed his belief that all religions "lead to God, only in different ways, and every man should go according to his own conscience, and settle things according to his own private way of looking at things."[16] He wanted them to argue, but they did not. He realized later that they likely thought his attitude "implied a fundamental and utter lack of faith, and a dependence on my own lights, and attachment to my own opinion"; furthermore, since "I did not believe in anything, ...anything I might say I believed would be only empty talk."[17]

Meanwhile, Merton's father was traveling, painting, and attending to an exhibition of his work in London. In the summer of 1928, he withdrew Merton from Lycée Ingres, saying they were moving to England.[18]

England 1928

Merton and his father lived with Owen's aunt and uncle in Ealing, West London. But he was soon enrolled in Ripley Court Preparatory School, a boarding school in Surrey. He connected with the studies and community, and joined all the students for Anglican services on Sundays. During holidays, Merton stayed at his great-aunt and uncle's home, where occasionally his father visited.

Toward the end of 1929, his father took Merton with him to live in Scotland. Owen became ill and was diagnosed at North Middlesex Hospital in London with a brain tumor.

In 1930, Merton was boarded at Oakham School in Rutland, England. From there, he traveled with his paternal grandparents to visit his hospitalized father. Owen died on January 16, 1931. Merton was assured by his grandfather Merton that he would provide for the youth, and Tom Bennett, Owen's physician and a former classmate in New Zealand, became Thomas's legal guardian. Bennett allowed Merton to use his unoccupied house in London during the holidays. In 1931, Merton visited Rome and Florence for a week. He traveled by ship to New York to see his maternal grandparents. After returning to Oakham, Merton became joint editor of the school magazine, the Oakhamian.

At that time, Merton identified as agnostic. In 1932, on a walking tour in Germany, he developed an infection on his foot; he ignored it but developed severe blood poisoning. He wrote later that

"the thought of God, the thought of prayer did not even enter my mind, either that day, or all the rest of the time that I was ill, or that whole year. Or if the thought did come to me, it was only as an occasion for its denial and rejection." His declared "creed" was "I believe in nothing."[19]

In September, he passed the entrance exam for Clare College, Cambridge. Then 18, he toured Europe: traveling to Paris and Marseille, walking to Hyères and Saint Tropez along the coast, and going by train to Genoa, Florence, and Rome.

Rome 1933

In February 1933, Merton lived in a small pensione by Palazzo Barberini and San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, from where he came to appreciate the beauty of Rome. He was drawn to its varied, ancient churches.[20] In the apse of Santi Cosma e Damiano, he was transfixed by a great mosaic of Jesus Christ come in judgment, and began to discover "Byzantine Christian Rome". He read the New Testament, from the Latin Vulgate, and had a mystical experience of his father's presence. He confronted the emptiness of his life, and began to pray more regularly. He visited Tre Fontane, a Trappist monastery in Rome, where he first thought of becoming a Trappist monk.[21]

United States 1933

Merton sailed by ship from Italy to the United States to visit his Jenkins grandparents in Douglaston for the summer,[7] before entering Clare College. Initially he continued to read his Latin Bible. He wanted to find a church to attend, and went to Zion Episcopal Church in Douglaston. Dissatisfied, he attended a Quaker meeting in Flushing. Merton appreciated the silence of the atmosphere but did not feel at home with the group. By mid-summer, he had lost nearly all the interest in organized religion again. At the end of the summer he returned to England.[22]

College

Cambridge University

In October 1933, Merton, now 18, entered Clare College as an undergraduate to study Modern Languages (French and Italian).[7] He drifted away and became isolated there, drinking to excess, and frequenting local pubs instead of studying. He began to see young women, and some friends called him a womanizer. He spent so freely that his guardian Bennett summoned him to London to try to talk sense to him. Most of Merton's biographers agree that he fathered a child with a woman he had a liaison with at Cambridge. Bennett discreetly settled a threatened legal action. This child has never been identified in published accounts.[23] Professor Alan Jacobs suggests that at least some of Merton's conduct may have been related to delayed grief from his father's death two years earlier.[8]

By this time Bennett had had enough. In a meeting in April, he arranged with Merton for his return to the US, promising not to tell his Jenkins grandparents about his excesses. In May Merton left Cambridge after completing his exams.

Columbia University

In January 1935, Merton, age 21, enrolled as a sophomore at Columbia University in Manhattan. He lived with his Jenkins grandparents in Douglaston, traveling daily by train and subway to the Columbia campus in Morningside Heights of upper Manhattan. There he established close and long-lasting friendships with Ad Reinhardt, who became known as a proto-minimalist painter, and poet Robert Lax.

Merton began an 18th-century English literature course during the spring semester taught by Mark Van Doren, a professor with whom he maintained a lifetime friendship. Van Doren was said to engage his students, sharing his love of literature, rather than teaching traditionally. Merton became interested in Communism at Columbia, which attracted many intellectuals during the Great Depression. He briefly joined the Young Communist League, attended one meeting, and never went back.

During summer break, his brother John Paul returned from Gettysburg Academy in Pennsylvania, and they spent the summer together. Merton later said that they saw every movie produced between 1934 and 1937. In the fall, John Paul enrolled at Cornell University, while Tom returned to Columbia. He began working for two school papers, a humor magazine called the Jester and the Columbia Review. Also on the Jester's staff were his friends Robert Lax and Ed Rice, who became a journalist. Rice later founded the Catholic magazine Jubilee, to which Merton frequently contributed essays. Merton also became a member of Alpha Delta Phi and joined the Philolexian Society, the campus literary and debate group.

In October 1935, in protest of Italy's invasion of Ethiopia, Merton joined a picket of the Casa Italiana at the university. It had been established in 1926, jointly sponsored by Columbia and the Italian government as a "university within a university". Merton also joined the local peace movement, having taken "the Oxford Pledge" against supporting any government in any war.

In 1936, Merton's grandfather, Samuel Jenkins, died. In February 1937, Merton read The Spirit of Medieval Philosophy by Étienne Gilson, which enlarged his sense of Catholicism. He had bought the book for a class on medieval French literature. He felt its explanation of God was logical and pragmatic. "That book, and the extraordinary variety of Catholic churches in Manhattan, almost all of which he seems to have visited, led Merton inexorably to an embrace of Catholicism."[8] Merton also began reading Aldous Huxley, whose book Ends and Means introduced him to mysticism. In August that year, Tom's grandmother died; she had been known in the family by the French term Bonnemaman (good mother).

In January 1938, Merton graduated from Columbia with a B.A. in English. He continued there, starting graduate work in English. In June, his friend Seymour Freedgood arranged a meeting with Mahanambrata Brahmachari, a Hindu monk visiting New York from the University of Chicago. Merton was impressed by him, believing the monk was profoundly centered in God. While Merton expected Brahmachari to recommend Hinduism, instead he advised Merton to reconnect with the spiritual roots of his own culture. He suggested Merton read The Confessions of Augustine and The Imitation of Christ. Merton read them both.[24]

Merton decided to explore Catholicism further. Finally, in August 1938, he decided to attend Mass and went to Corpus Christi Church, located near the Columbia campus on West 121st Street in Morningside Heights. The ritual of Mass was foreign to him, but he listened attentively. Following this, Merton began to read more extensively in Catholicism. As part of his graduate work, he was writing a thesis on William Blake, whose spiritual symbolism he was coming to appreciate in new ways.

One evening in September, Merton was reading about Gerard Manley Hopkins' conversion to Catholicism and becoming a priest. Suddenly, he could not shake the sense that he, too, should follow such a path. He headed quickly to the Corpus Christi Church rectory, where he met Fr. George Barry Ford, and expressed his desire to become Catholic. In the following weeks Merton started catechism, learning the basics of his new faith. On November 16, 1938, Thomas Merton underwent the rite of baptism at Corpus Christi Church and received Holy Communion.[25] On February 22, 1939, Merton received his M.A. in English from Columbia University. Merton decided he would pursue his Ph.D. at Columbia and moved from Douglaston to Greenwich Village.

In January 1939, Merton had heard good things about a part-time teacher named Daniel Walsh, so he decided to take a course with him on Thomas Aquinas. Through Walsh, Merton was introduced to Jacques Maritain at a lecture on Catholic Action, which took place at a Catholic Book Club meeting the following March. Merton and Walsh developed a lifelong friendship. Walsh convinced Merton that Thomism was not for him. On May 25, 1939, Merton received Confirmation as a Catholic at Corpus Christi, and took the confirmation name James.

Franciscans

Vocation

In October 1939, Merton invited friends to sleep at his place following a long night out at a jazz club. Over breakfast, Merton told them of his desire to become a priest. Soon after this, Merton visited Fr. Ford at Corpus Christi to share his feeling. Ford agreed with Merton, but added that he felt Merton was suited for the priesthood of the diocesan priest and advised against joining an order.

Soon after, Merton met with his teacher Dan Walsh, whose advice he trusted. Walsh disagreed with Ford's assessment. Instead, he felt Merton was spiritually and intellectually suited for a priestly vocation in an order. They discussed the Jesuits, Cistercians and Franciscans. Merton had appreciated what he had read of Saint Francis of Assisi; as a result, he felt that might be the direction in which he was being called.

Walsh set up a meeting with a Fr. Edmund Murphy, a friend at the monastery of St. Francis of Assisi on 31st Street. The interview went well and Merton was given an application, as well as Fr. Murphy's personal invitation to become a Franciscan friar. He noted that Merton would not be able to enter the novitiate until August 1940 because that was the only month in which they accepted novices. Merton was excited, yet disappointed that it would be a year before he would fulfill his calling.

By 1940 Merton began to doubt about whether he was fit to be a Franciscan. He felt he had not been candid about his past with Fr. Murphy or Dan Walsh. Merton arranged to see Fr. Murphy. Compassionated during the meeting, Fr. Murphy told Tom he ought to return the next day after the priest could consider this new information. At that time, Fr. Murphy told Merton that he no longer felt Merton was suitable material for a vocation as a Franciscan friar, and that the August novitiate was now full. Merton believed that his religious calling was finished.

St. Bonaventure University

In early August 1940, with the Franciscan novitiate closed to him, Merton went to Olean, New York, to stay with friends, including Robert Lax and Ed Rice, at a cottage where they had vacationed the summer before. Merton now needed a job. Nearby was St. Bonaventure University, a Franciscan university he had learned about through Lax a year before. Merton went to the university for an interview with its president, Fr. Thomas Plassman. He had an opening in the English department and hired Merton on the spot. Merton had started seeking a job at St. Bonaventure because he still harbored a desire to be a friar; he decided that he could at least live among them even if he could not be one. St. Bonaventure University holds a repository of Merton materials.[26]

In September 1940, Merton moved into a dormitory on campus. (His old room in Devereux Hall is marked by a sign above the door.) While Merton's stay at Bonaventure would prove brief, the time was pivotal for him. While teaching there, he entered more deeply into his prayer life and his spiritual life blossomed. He all but gave up drinking, quit smoking, stopped going to movies, and became more selective in his reading. In his own way he was undergoing a kind of lay renunciation of worldly pleasures. In April 1941, Merton went to a retreat he had booked for Holy Week at the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani near Bardstown, Kentucky.

At St. Bonaventure with Gethsemani on his mind, Merton returned to teaching. Still unsure about his future plans, in May 1941 Merton resorted to the ancient bibliomantic ritual of the Sortes Sanctorum. Using his old Vulgate Bible, purchased in Italy in 1933, he would randomly point his finger at a page, to see if a chance selection would reveal a sign. On his second try Merton laid his finger on a verse reading "ecce eris tacens" (Luke 1:20 DR.LV.NVUL; Latin for '"behold, thou shalt be silent"'). Immediately Merton thought of the Cistercians.

In August 1941, Merton attended a talk at the school given by Catherine de Hueck. Hueck had founded the Friendship House in Toronto and its sister house in Harlem, which Merton visited. Appreciative of the mission of Hueck and Friendship House, which was racial harmony and charity, he decided to volunteer there for two weeks.[27] Harlem was such a different place, full of poverty and prostitution. Merton felt especially troubled by the situation of children being raised in that environment. Friendship House had a profound influence on Merton, and he would refer to it often in his later writing.

In November 1941, Hueck asked if Merton would consider becoming a full-time member of Friendship House, to which Merton was noncommittal. In early December Merton let Hueck know that he would not be joining Friendship House, explaining his persistent attraction to the priesthood.

Monastic life

.jpg.webp)

On December 10, 1941, Thomas Merton arrived at the Abbey of Gethsemani and spent three days at the monastery guest house, waiting for acceptance into the Order. The novice master would come to interview Merton, gauging his sincerity and qualifications. In the interim, Merton was put to work polishing floors and scrubbing dishes. On December 13 he was accepted into the monastery as a postulant by Frederic Dunne, Gethsemani's abbot since 1935. Merton's first few days did not go smoothly. He had a severe cold from his stay in the guest house, where he sat in front of an open window to prove his sincerity. During his initial weeks at Gethsemani, Merton studied the complicated Cistercian sign language and daily work and worship routine.

In March 1942, during the first Sunday of Lent, Merton was accepted as a novice at the monastery. In June, he received a letter from his brother John Paul stating he was soon to leave for the war and would be coming to Gethsemani to visit before leaving. On July 17 John Paul arrived in Gethsemani and the two brothers did some catching up. John Paul expressed his desire to become Catholic, and by July 26 was baptized at a church in nearby New Haven, Kentucky, leaving the following day. This would be the last time the two saw each other. John Paul died on April 17, 1943, when his plane failed over the English Channel. A poem by Merton to John Paul appears in The Seven Storey Mountain.

Writer

Merton kept journals throughout his stay at Gethsemani. Initially, he felt writing to be at odds with his vocation, worried it would foster a tendency to individuality. Fortunately his superior, Dunne, saw that Merton had both a gifted intellect and talent for writing. In 1943 Merton was tasked to translate religious texts and write biographies on the saints for the monastery. Merton approached his new writing assignment with the same fervor and zeal he displayed in the farmyard.

On March 19, 1944, Merton made his temporary profession of vows and was given the white cowl, black scapular and leather belt. In November 1944 a manuscript Merton had given to friend Robert Lax the previous year was published by James Laughlin at New Directions: a book of poetry titled Thirty Poems. Merton had mixed feelings about the publishing of this work, but Dunne remained resolute over Merton continuing his writing. In 1946 New Directions published another poetry collection by Merton, A Man in the Divided Sea, which, combined with Thirty Poems, attracted some recognition for him. The same year Merton's manuscript for The Seven Storey Mountain was accepted by Harcourt Brace & Company for publication. The Seven Storey Mountain, Merton's autobiography, was written during two-hour intervals in the monastery scriptorium as a personal project.

By 1947 Merton was more comfortable in his role as a writer. On March 19 he took his solemn vows, a commitment to live out his life at the monastery. He also began corresponding with a Carthusian at St. Hugh's Charterhouse in England. Merton had harbored an appreciation for the Carthusian Order since coming to Gethsemani in 1941, and would later come to consider leaving the Cistercians for that Order. On July 4 the Catholic journal Commonweal published an essay by Merton titled Poetry and the Contemplative Life.

In 1948 The Seven Storey Mountain was published to critical acclaim, with fan mail to Merton reaching new heights. Merton also published several works for the monastery that year, which were: Guide to Cistercian Life, Cistercian Contemplatives, Figures for an Apocalypse, and The Spirit of Simplicity. That year Saint Mary's College (Indiana) also published a booklet by Merton, What Is Contemplation? Merton published as well that year a biography, Exile Ends in Glory: The Life of a Trappistine, Mother M. Berchmans, O.C.S.O. Merton's abbot, Dunne, died on August 3, 1948, while riding on a train to Georgia. Dunne's passing was painful for Merton, who had come to look on the abbot as a father figure and spiritual mentor. On August 15 the monastic community elected Dom James Fox, a former US Navy officer, as their new abbot. In October Merton discussed with him his ongoing attraction to the Carthusian and Camaldolese Orders and their eremitical way of life, to which Fox responded by assuring Merton that he belonged at Gethsemani. Fox permitted Merton to continue his writing, Merton now having gained substantial recognition outside the monastery. On December 21 Merton was ordained as a subdeacon. From 1948 on, Merton identified as an anarchist.[28]

On January 5, 1949, Merton took a train to Louisville and applied for American citizenship. Published that year were Seeds of Contemplation, The Tears of Blind Lions, The Waters of Siloe, and the British edition of The Seven Storey Mountain under the title Elected Silence. On March 19, Merton became a deacon in the Order, and on May 26 (Ascension Thursday) he was ordained a priest, saying his first Mass the following day. In June, the monastery celebrated its centenary, for which Merton authored the book Gethsemani Magnificat in commemoration. In November, Merton started teaching mystical theology to novices at Gethsemani, a duty he greatly enjoyed. By this time Merton was a huge success outside the monastery, The Seven Storey Mountain having sold over 150,000 copies. In subsequent years Merton would author many other books, amassing a wide readership. He would revise Seeds of Contemplation several times, viewing his early edition as error-prone and immature. A person's place in society, views on social activism, and various approaches toward contemplative prayer and living became constant themes in his writings.

In this particularly prolific period of his life, Merton is believed to have been suffering from a great deal of loneliness and stress. One incident indicative of this is the drive he took in the monastery's jeep, during which Merton, acting in a possibly manic state, erratically slid around the road and almost caused a head-on collision.[29]

During long years at Gethsemani, Merton changed from the passionately inward-looking young monk of The Seven Storey Mountain to a more contemplative writer and poet. Merton became well known for his dialogues with other faiths and his non-violent stand during the race riots and Vietnam War of the 1960s.

By the 1960s, he had arrived at a broadly human viewpoint, one deeply concerned about the world and issues like peace, racial tolerance, and social equality. He had developed a personal radicalism which had political implications but was not based on ideology, rooted above all in non-violence. He regarded his viewpoint as based on "simplicity" and expressed it as a Christian sensibility. His New Seeds of Contemplation was published in 1962. In a letter to Nicaraguan Catholic priest, liberation theologian and politician Ernesto Cardenal (who entered Gethsemani but left in 1959 to study theology in Mexico), Merton wrote: "The world is full of great criminals with enormous power, and they are in a death struggle with each other. It is a huge gang battle, using well-meaning lawyers and policemen and clergymen as their front, controlling papers, means of communication, and enrolling everybody in their armies."[30]

Merton finally achieved the solitude he had long desired while living in a hermitage on the monastery grounds in 1965. Over the years he had occasional battles with some of his abbots about not being allowed out of the monastery despite his international reputation and voluminous correspondence with many well-known figures of the day.

At the end of 1968, the new abbot, Flavian Burns, allowed him the freedom to undertake a tour of Asia, during which he met the Dalai Lama in India on three occasions, and also the Tibetan Buddhist Dzogchen master Chatral Rinpoche, followed by a solitary retreat near Darjeeling, India. In Darjeeling, he befriended Tsewang Yishey Pemba, a prominent member of the Tibetan community.[31][32] Then, in what was to be his final letter, he noted, "In my contacts with these new friends, I also feel a consolation in my own faith in Christ and in his dwelling presence. I hope and believe he may be present in the hearts of all of us."[33]

Merton's role as a writer is explored in novelist Mary Gordon's On Merton (2019).[34]

Personal life

.jpg.webp)

According to The Seven Storey Mountain, the youthful Merton loved jazz, but by the time he began his first teaching job he had forsaken all but peaceful music. Later in life, whenever he was permitted to leave Gethsemani for medical or monastic reasons, he would catch what live jazz he could, mainly in Louisville or New York.

In April 1966, Merton underwent surgery to treat debilitating back pain. While recuperating in a Louisville hospital, he fell in love with Margie Smith,[35] a student nurse assigned to his care. (He referred to her in his diary as "M.") He wrote poems to her and reflected on the relationship in "A Midsummer Diary for M." Merton struggled to maintain his vows while being deeply in love. It is not known if he ever consummated the relationship.[note 1]

Death

On December 10, 1968, Merton was at a Red Cross retreat center named Sawang Kaniwat in Samut Prakan, a province near Bangkok, Thailand, attending a monastic conference.[36] After giving a talk at the morning session, he was found dead later in the afternoon in the room of his cottage, wearing only shorts, lying on his back with a short-circuited Hitachi floor fan lying across his body.[37] His associate, Jean Leclercq, states: "In all probability the death of Thomas Merton was due in part to heart failure, in part to an electric shock."[38] Since there was no autopsy, there was no suitable explanation for the wound in the back of Merton's head, "which had bled considerably."[39] Arriving from the cottage next to Merton's, the Primate of the Benedictine Order and presiding officer of the conference, Rembert Weakland, anointed Merton.[40]

His body was flown back to the United States on board a US military aircraft returning from Vietnam. He is buried at the Gethsemani Abbey.

In 2016, theologian Matthew Fox claimed that Merton had been assassinated by agents of the Central Intelligence Agency. James W. Douglass made a similar claim in 1997. In 2018, Hugh Turley and David Martin published The Martyrdom of Thomas Merton: An Investigation, questioning the claim of accidental electrocution.[41][42]

Spirituality beyond Catholicism

Eastern religions

Merton was first exposed to and became interested in Eastern religions when he read Aldous Huxley's Ends and Means in 1937, the year before his conversion to Catholicism.[43] Throughout his life, he studied Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, Hinduism, Sikhism, Jainism, and Sufism in addition to his academic and monastic studies.[44]

While Merton was not interested in what these traditions had to offer as doctrines and institutions, he was deeply interested in what each said of the depth of human experience. He believed that for the most part, Christianity had forsaken its mystical tradition in favor of Cartesian emphasis on "the reification of concepts, idolization of the reflexive consciousness, flight from being into verbalism, mathematics, and rationalization."[45] Eastern traditions, for Merton, were mostly untainted by this type of thinking and thus had much to offer in terms of how to think of and understand oneself.

Merton was perhaps most interested in—and, of all of the Eastern traditions, wrote the most about—Zen. Having studied the Desert Fathers and other Christian mystics as part of his monastic vocation, Merton had a deep understanding of what it was those men sought and experienced in their seeking. He found many parallels between the language of these Christian mystics and the language of Zen philosophy.[46]

In 1959, Merton began a dialogue with D. T. Suzuki which was published in Merton's Zen and the Birds of Appetite as "Wisdom in Emptiness". This dialogue began with the completion of Merton's The Wisdom of the Desert. Merton sent a copy to Suzuki with the hope that he would comment on Merton's view that the Desert Fathers and the early Zen masters had similar experiences. Nearly ten years later, when Zen and the Birds of Appetite was published, Merton wrote in his postface that "any attempt to handle Zen in theological language is bound to miss the point", calling his final statements "an example of how not to approach Zen."[47] Merton struggled to reconcile the Western and Christian impulse to catalog and put into words every experience with the ideas of Christian apophatic theology and the unspeakable nature of the Zen experience.

In keeping with his idea that non-Christian faiths had much to offer Christianity in experience and perspective and little or nothing in terms of doctrine, Merton distinguished between Zen Buddhism, an expression of history and culture, and Zen.[46] What Merton meant by Zen Buddhism was the religion that began in China and spread to Japan as well as the rituals and institutions that accompanied it. By Zen, Merton meant something not bound by culture, religion or belief. In this capacity, Merton was influenced by Aelred Graham's book Zen Catholicism of 1963.[48][note 2] With this idea in mind, Merton's later writings about Zen may be understood to be coming more and more from within an evolving and broadening tradition of Zen which is not particularly Buddhist but informed by Merton's monastic training within the Christian tradition.[49]

American Indian spirituality

Merton also explored American Indian spirituality. He wrote a series of articles on American Indian history and spirituality for The Catholic Worker, The Center Magazine, Theoria to Theory, and Unicorn Journal.[50] He explored themes such as American Indian fasting[51] and missionary work.[52]

Legacy

Merton's influence has grown since his death and he is widely recognized as an important 20th-century Catholic mystic and thinker. Interest in his work contributed to a rise in spiritual exploration beginning in the 1960s and 1970s in the United States. Merton's letters and diaries reveal the intensity with which their author focused on social justice issues, including the civil rights movement and proliferation of nuclear arms. He had prohibited their publication for 25 years after his death. Publication raised new interest in Merton's life.

The Abbey of Gethsemani benefits from the royalties of Merton's writing.[53] In addition, his writings attracted much interest in Catholic practice and thought, and in the Cistercian vocation.

In recognition of Merton's close association with Bellarmine University, the university established an official repository for Merton's archives at the Thomas Merton Center on the Bellarmine campus in Louisville, Kentucky.[54]

The Thomas Merton Award, a peace prize, has been awarded since 1972 by the Thomas Merton Center for Peace and Social Justice in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[55]

The 2015, in tribute to the centennial year of Merton's birth in The Festival of Faiths in Louisville Kentucky honored the life and work of Thomas Merton with Sacred Journey’s the Legacy of Thomas Merton.[56]

An annual lecture in his name is given at his alma mater, Columbia University.

The campus ministry building at St. Bonaventure University, the school where Merton taught English briefly between graduating from Columbia University with his M.A. in English and entering the Trappist Order, is named after him. St. Bonaventure University also holds an important repository of Merton materials worldwide.[57]

Bishop Marrocco/Thomas Merton Catholic Secondary School in downtown Toronto, Ontario, Canada, which was formerly named St. Joseph's Commercial and was founded by the Sisters of St. Joseph, is named in part after him.

Some of Merton's manuscripts that include correspondence with his superiors are located in the library of the Monastery of the Holy Spirit in Conyers, Georgia.

Merton was one of four Americans mentioned by Pope Francis in his speech to a joint meeting of the United States Congress on September 24, 2015. Francis said, "Merton was above all a man of prayer, a thinker who challenged the certitudes of his time and opened new horizons for souls and for the Church. He was also a man of dialogue, a promoter of peace between peoples and religions."[58]

Merton is honored with a feast day on the liturgical calendar of some church members of the Anglican Communion.[59]

In popular culture

Merton's life was the subject of The Glory of the World, a play by Charles L. Mee. Roy Cockrum, a former monk who won the Powerball lottery in 2014, helped finance the production of the play in New York. Prior to New York the play was being shown in Louisville, Kentucky.[60]

In the movie First Reformed, written and directed by Paul Schrader, Ethan Hawke's character (a middle-aged Protestant reverend) is influenced by Merton's work.[61]

Notes

- This issue is discussed in detail in Shaw, Mark (2009). Beneath The Mask of Holiness. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-61653-0.

In Learning to Love, Merton's diary entries discuss his various meetings with Smith. In several cases he expressly denies sexual consummation, e.g. p. 52. On June 11, 1966, Merton arranged to 'borrow' the Louisville office of his psychologist, Dr. James Wygal, to get together with Smith, see p. 81. The diary entry for that day notes that they had a bottle of champagne. A parenthetical with dots at that point in the narrative indicates that further details regarding this meeting were not published in Learning to Love. In the June 14 entry, Merton notes that he had found out the night before that a brother at the abbey had overheard one of his phone conversations with Smith and had reported it to Dom James, Abbot of Gethsemani. Merton wondered which phone conversation had been monitored, saying that one he had the morning following his meeting with Smith at Wygal's office would be "the worst!!", see p. 82. Merton's June 14 entry note his discussions with Abbot James on this matter, and his intent to follow the Abbot's instruction to end his romantic relationship with M. In his entry for July 12, 1966, Merton says regarding Smith,

"Yet there is no question I love her deeply ... I keep remembering her body, her nakedness, the day at Wygal's, and it haunts me ... I could have been enslaved to the need for her body after all. It is a good thing I called it off [i.e., a proposed visit by Smith to Gethsemani to speak with Merton there following their break-up]." See p. 94.

In Learning to Love reveals that Merton remained in contact with Marge after his July 12, 1966 entry (p.94) and after he recommitted himself to his vows (p. 110). He saw her again on July 16, 1966, and wrote:She says she thinks of me all the time (as I do of her) and her only fear is that being apart and not having news of each other, we may gradually cease to believe that we are loved, that the other's love for us goes on and is real. As I kissed her she kept saying, 'I am happy, I am at peace now.' And so was I" (p. 97).

Despite good intentions, he continued to contact her by phone when he left the monastery grounds. He wrote on January 18, 1967 that "last week" he and two friends "drank some beer under the loblollies at the lake--should not have gone to Bardstown and Willett's in the evening. Conscience stricken for this the next day. Called M. from filling station outside Bardstown. Both glad" (p. 186). - "Can a philosophy of life which originated in India centuries before Christ—still accepted as valid, in one or other of its many variants, by several hundred millions of our contemporaries—be of service to Catholics, or those interested in Catholicism, in elucidating certain aspects of the Church's own message? The possibility cannot be ruled out. To the point is St. Ambrose's well-known dictum, endorsed by St. Thomas Aquinas, being a gloss on 1 Corinthians 12:3, 'All that is true, by whomsoever it has been said, is from the Holy Ghost.'" Graham, Aelred (1963). Zen Catholicism. Harvest book. 118. San Diego, CA: Harcourt, Brace & World. p. 10.

References

- Reichardt, Mary R. (2004). Encyclopedia of Catholic Literature, Volume 2. Greenwood Press. p. 450. ISBN 0-313-32803-X.

- "Chronology of Merton's life", Thomas Merton Center, Bellarmine University; accessed April 17, 2018.

- Matthew Fox, A Way to God: Thomas Merton's Creation Spirituality Journey, New World Library (2016), p. xvi

- "FICTION: 1949 BESTSELLERS: Non Fiction". TIME. December 19, 1949. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- "Religion: The Mountain". TIME. April 11, 1949.

- National Review's list of the 100 best non-fiction books of the century National Review website

- "Thomas Merton's Life and Work", The Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University

- Jacobs, Alan. "The Modern Monkhood of Thomas Merton", The New Yorker, December 28, 2018

- Seven Storey Mountain, pp. 7–9.

- Seven Storey Mountain pp. 15–18.

- Seven Storey Mountain, pp. 20–22.

- Seven Storey Mountain, pp. 30–31.

- Seven Storey Mountain, pp. 31–41.

- Cooper, David (2008). Thomas Merton's Art of Denial: The Evolution of a Radical Humanist. University of Georgia Press. pp. 81–82. ISBN 9780820332161.

- Seven Storey Mountain pp. 57–58.

- Seven Storey Mountain pp. 63–64.

- Seven Storey Mountain pp. 63–64.

- Cunningham, Lawrence (1999). Thomas Merton and the Monastic Vision. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 5.

- Seven Storey Mountain p. 108.

- Seven Storey Mountain p. 107.

- Seven Storey Mountain p. 114.

- Merton, Thomas. The Seven Storey Mountain (Fiftieth Anniversary ed.). p. 127.

- Elie, Paul (2003). The Life You Save May Be Your Own: An American Pilgrimage. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 41–42. ISBN 9780374529215.

- Niebuhr, Gustav (November 1, 1999). "Mahanambrata Brahmachari Is Dead at 95". New York Times. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- Thomas Merton's paradise journey: writings on contemplation, by William Henry Shannon, Thomas Merton, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2000 p. 278.

- "The Thomas Merton Archives". St. Bonaventure University. May 11, 2013. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013.

- Pennington, M. Basil (2005). Thomas Merton: I have seen what I was looking for : selected spiritual writings. New City Press. p. 12. ISBN 1-56548-225-5.

- Labrie, R. (2001). Thomas Merton and the Inclusive Imagination. University of Missouri Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-8262-6279-0. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- Waldron, Robert G. (2014). The Wounded Heart of Thomas Merton. Paulist Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0809146840.

- Letter, November 17, 1962, quoted in Monica Furlong's Merton: a Biography p. 263.

- "A Man of Many Firsts". KUENSEL. December 11, 2011. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

- Merton, Thomas (February 1975). The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton. New Directions. ISBN 0-8112-0570-3.

- "Religion: Mystic's Last Journey". TIME. August 6, 1973. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- Gordon, Mary (2019). On Merton. Shambhala Publications. ISBN 978-1-6118-0337-2.

- "Book on monk Thomas Merton's love affair stirs debate". USA Today. December 23, 2009. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- Moffitt, John (1970). A New Charter For Monasticism. Notre Dame Press. pp. 332–335.

- Hugh Turley and David Martin, The Martyrdom of Thomas Merton: An Investigation,

- "Monastic Interreligious Dialogue - Final Memories of Thomas Merton". December 12, 2008. Archived from the original on December 12, 2008.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Michael Mott, The Seven Mountains of Thomas Merton, pp. 567–568. Hugh Turley and David Martin, The Martyrdom of Thomas Merton: An Investigation, p. 84.

- Weakland, Rembert (2009). A Pilgrim in a Pilgrim Church. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 166. ISBN 9780802863829.

- "The Martyrdom of Thomas Merton: An Investigation". July 9, 2018.

- Soline Humbert (December 3, 2018). "This turbulent monk: Did the CIA kill vocal war critic Thomas Merton?". Irish Times.

- Solitary Explorer: Thomas Merton's Transforming Journey p.100.

- "Lighthouse Trails Research Project - Exposing the New Spirituality".

- Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander p. 285.

- Solitary Explorer: Thomas Merton's Transforming Journey p. 105.

- Zen and the Birds of Appetite p. 139.

- Solitary Explorer: Thomas Merton's Transforming Journey p. 106.

- Solitary Explorer: Thomas Merton's Transforming Journey p. 112.

- Merton, Thomas (1976). Ishi Means Man. Unicorn Press.

- Merton, Thomas (1976). Ishi Means Man. Unicorn Press. p. 17.

- Merton, Thomas (1976). Ishi Means Man. Unicorn Press. p. 37.

- Robert Giroux (October 11, 1998). "Thomas Merton's Durable Mountain". The New York Times.

- "Merton Center in Louisville". National Catholic Reporter. November 11, 2012. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- "Thomas Merton Award goes to climate change activist". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- Elson, Martha. "20th Festival of Faiths honors Merton". The Courier-Journal. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20130511215042/http://web.sbu.edu/friedsam/archives/mertonweb/index.html

- "Address of the Holy Father". The Vatican. September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- Polynesia, Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and. "Lectionary and Worship / Resources / Home - Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia".

- Lunden, Jeff (January 16, 2016). "'Glory Of The World' Is More Wacky Birthday Party Than Traditional Play". NPR.org.

- Jones, J.R. "Paul Schrader's First Reformed finds pride at the root of despair". Chicago Reader. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

Further reading

- 2019 - Gordon, Mary, On Merton (2019), Shambhala Publications, ISBN 978-1611803372

- 2018 - Turley, Hugh and David Martin, The Martyrdom of Thomas Merton (2018), McCabe, ISBN 978-1548077389

- 2017 - Merton, Thomas and Paul M. Pearson. Beholding Paradise: The Photographs of Thomas Merton. Paulist Press.

- 2015 - Lipsey, Roger. Make Peace before the Sun Goes Down: The Long Encounter of Thomas Merton and His Abbot, James Fox. Boulder, CO. Shambhala Publications ISBN 978-1611802252

- 2014 - Shaw, Jeffrey M. Illusions of Freedom: Thomas Merton and Jacques Ellul on Technology and the Human Condition. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1625640581.

- 2014 - Horan, Daniel. The Franciscan Heart of Thomas Merton: A New Look at the Spiritual Inspiration of His Life, Thought, and Writing Notre Dame: Ave Maria Press. (2014). ISBN 978-1594714221

- 2008 – Graham, Terry, The Strange Subject - Thomas Merton's Views on Sufism at the Wayback Machine (archived June 20, 2010), 2008, SUFI: a journal of Sufism, Issue 30.

- 2007 – Deignan, Kathleen, A Book of Hours: At Prayer With Thomas Merton (2007), Sorin Books, ISBN 1-933495-05-7.

- 2006 – Weis, Monica, Paul M. Pearson, Kathleen P. Deignan, Beyond the Shadow and the Disguise: Three Essays on Thomas Merton (2006), The Thomas Merton Society of Great Britain and Ireland, ISBN 0-9551571-1-0.

- 2003 – Merton, Thomas, Kathleen Deignan Ed., John Giuliani, Thomas Berry, When The Trees Say Nothing (2003), Sorin Books, ISBN 1-893732-60-6.

- 2002 – Shannon, William H., Christine M. Bochen, Patrick F. O'Connell The Thomas Merton Encyclopedia (2002), Orbis Books, ISBN 1-57075-426-8.

- 1997 – Merton, Thomas, "Learning to Love", The Journals of Thomas Merton, Volume Six 1966-1967(1997), ISBN 0-06-065485-6. (see notes for page numbers)

- 1992 – Shannon, William H., Silent Lamp: The Thomas Merton Story (1992), The Crossroad Publishing Company, ISBN 0-8245-1281-2, biography.

- 1991 – Forest, Jim, Living With Wisdom: A Life of Thomas Merton (revised edition) (2008), Orbis Books, ISBN 978-1-57075-754-9, illustrated biography.

- 1984 – Mott, Michael, The Seven Mountains of Thomas Merton (1984), Harvest Books 1993: ISBN 0-15-680681-9, authorized biography.

- 1978 – Merton, Thomas, The Seven Storey Mountain (1978), A Harvest/HBJ Book, ISBN 0-15-680679-7. (see notes for page numbers)