War of the Heavenly Horses

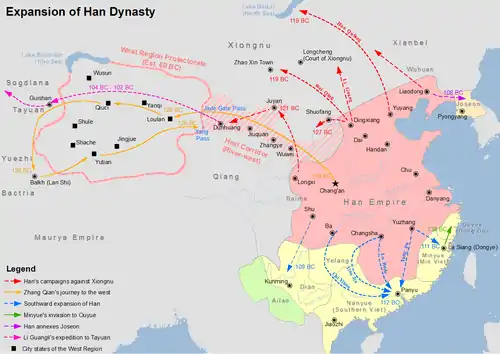

The War of the Heavenly Horses (simplified Chinese: 天马之战; traditional Chinese: 天馬之戰; pinyin: Tiānmǎ zhī Zhàn) or the Han–Dayuan War (simplified Chinese: 汉宛战争; traditional Chinese: 漢宛戰爭; pinyin: Hàn Yuān Zhànzhēng) was a military conflict fought in 104 BC and 102 BC between the Chinese Han dynasty and the kingdom known to the Chinese as Dayuan, in the Ferghana Valley at the easternmost end of the former Persian empire, now the easternmost part of Uzbekistan. The result was a Han victory, and a temporary expansion of its hegemony deep into central Asia.[1][2]

| War of the Heavenly Horses | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Han dynasty | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Wugua Jianmi | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1st (104 BC): 20,000 infantry 6,000 cavalry 2nd (102 BC): 60,000 infantry 30,000 cavalry 100,000 oxen 20,000 donkeys and camels |

| ||||||

Emperor Wu of Han had received reports from diplomat Zhang Qian that Dayuan owned tall and powerful horses ("heavenly horses") that could help fight against the Xiongnu. He sent envoys to survey the region and purchase horses. Dayuan refused the deal, resulting in the death of one of the Han ambassadors, and confiscated the gold sent as payment. So the Han sent an army to subdue Dayuan. Their first incursion failed, but a second, larger force defeated Dayuan, installed a regime favorable to the Han, and won enough horses to later build a cavalry strong enough to defeat the Xiongnu in the Han–Xiongnu War.[3]

Background

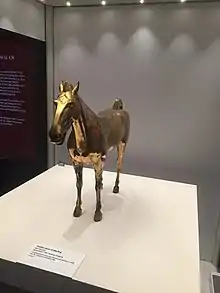

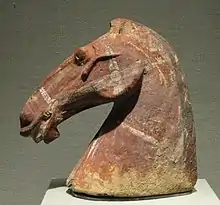

The horses

Emperor Wudi decided to defeat the nomadic steppe Xiongnu, who had historically harassed the Han dynasty for decades before. So in 139 BC he sent an envoy by the name of Zhang Qian to survey the west and forge a military alliance with the Yuezhi against the Xiongnu.[1][4] On the way to Central Asia through the Gobi desert, Zhang was captured twice. On his return, he impressed the emperor with his description of the "heavenly horses" of Dayuan.[5]

According to the Book of the Later Han (penned by a Chinese historian during the fifth century and considered an authoritative record of the Han history between 25 and 220), at least five or six, and perhaps as many as ten diplomatic groups were dispatched annually by the Han court to Central Asia during this period to buy horses."[1]

The horses have since captured the popular imagination of China, leading to horse carvings, breeding grounds in Gansu, and up to 430,000 such horses in the cavalry during even the Tang dynasty.[1]

Xiongnu

For decades prior the Han followed a policy of heqin (和亲) sending tribute and princesses to marry the Xiongnu shanyu to maintain peace. This changed when Emperor Wudi came into power, when the Han adopted and revived a policy to defeat the Xiongnu.[4]

Dayuan

Records of the Grand Historian and the Book of Han describe the Dayuan as numbering several hundred thousand people living in 70 walled cities of varying size. They grew rice and wheat, and made wine from grapes.[6]

Dayuan was one of the furthest western states to send envoys to the Han court. However unlike the other envoys, the ones from Dayuan did not conform to the proper Han rituals and behaved with great arrogance and self-assurance, believing they were too far away to be in any danger of invasion. Dayuan was also situated near the Xiongnu at this point, who were held in great respect for they had caused the Yuezhi much suffering. An envoy from the Xiongnu bearing the credentials of the Chanyu was provided with food and escort. In comparison, a Han envoy received no mounts he did not buy himself and no food unless he handed out silks and other goods. Han envoys also had a reputation for wealth in the west, thus they were charged exorbitant fees wherever they went, causing the Han no small amount of grief.[7] However the historian Sima Qian provides a different account:

The envoys were all sons of poor families who handled the government gifts and goods that were entrusted to them as though they were private property and looked for opportunities to buy goods at a cheap price in the foreign countries and make a profit on their return to China. The men of the foreign lands soon became disgusted when they found that each of the Han envoys told some different story and, considering that the Han armies were too far away to worry about, refused to supply the envoys with food and provisions, making things very difficult for them. The Han envoys were soon reduced to a state of destitution and distress and, their tempers mounting, fell to quarrelling and even attacking each other.[8]

— Shiji

Among the goods western envoys brought with them were the "heavenly horses", which the emperor took a liking to. He sent a trade mission with 1,000 pieces of gold and a golden horse to purchase these horses from Dayuan. Dayuan had at this point already been trading with the Han for quite some time and benefited greatly from it. Not only were they overflowing with eastern goods, they also learned from Han soldiers how to cast metal into coins and weapons. Thus they had no great reason to accept the Han trade offer, reasoning:

The Han is far away from us and on several occasions has lost men in the salt-water wastes between our country and China. Yet if the Han parties go farther north, they will be harassed by the Xiongnu, while if they try to go south they will suffer from lack of water and fodder. Moreover, there are many places along the route where there are no cities whatsoever and they are apt to run out of provisions. The Han embassies that have come to us are made up of only a few hundred men, and yet they are always short of food and over half the men die on the journey. Under such circumstances how could the Han possibly send a large army against us? What have we to worry about? Furthermore, the horses of Ershi are one of the most valuable treasures of the state![9]

The Han envoys cursed the men of Dayuan and smashed the golden horse they had brought. Enraged by this act of contempt, the nobles of Dayuan ordered Yucheng (modern Uzgen), which lay on their eastern borders, to attack and kill the envoys and seize their goods. Upon receiving word of the trade mission's demise, Emperor Wu decided to dispatch a punitive expedition against Dayuan. Li Guangli, brother of Emperor Wu's favorite concubine, Lady Li, was appointed Ershi General and sent against Dayuan with 6,000 cavalry and 20,000 young men drawn from the undesirables among the border kingdoms.[9]

First expedition (104 BC)

In the autumn of 104 BC, Li Guangli set out with an army of 6,000 cavalry and 20,000 infantry. While crossing the Tarim Basin and the Taklamakan Desert (of modern Xinjiang), Li's army was forced to attack the nearby oasis states because they refused to provide them with supplies. Sometimes they were unable to overcome the oasis states. If the siege lasted for more than a few days, the army moved on without any supplies. Due to these numerous petty conflicts, the army became exhausted and was reduced to starvation after their supplies ran out. By the time they neared Dayuan, Li had already lost too much manpower to continue the campaign. After suffering a defeat at Yucheng, Li concluded that their current strength would not be sufficient to take the Dayuan capital, Ershi (Khujand), and therefore returned to Dunhuang.[10]

Second expedition (102 BC)

The court officials wanted to disband Li's expeditionary army and concentrate their resources toward fighting the Xiongnu. Emperor Wu refused out of fear that failure to subdue Dayuan would result in a loss of prestige with the western states. He responded by giving Li a much larger army as well as supply animals. In the autumn of 102 BC, Li set out with an army of 60,000 penal recruits and mercenaries (collectively called 惡少年, literally meaning "bad boys") and 30,000 horses along with a large number of supply animals including 100,000 oxen and 20,000 donkeys and camels. This time the expedition was well provisioned and had no problem dealing with the oasis states.[10][11]

Facing a determined Han expedition army, most of the Western Regions states simply surrendered without a fight upon seeing the overwhelming display of power. The only state that put up any resistance was Luntai, for which Li had its populace massacred. Despite meeting no major setbacks and bypassing Yucheng entirely, Li still lost half his army to the harsh terrain by the time they reached Dayuan.[10] Upon arriving at Ershi, Li immediately laid siege to it. A force of Wusun cavalry 2,000 strong was also present at the request of Emperor Wu, but they refused to take part in the siege out of fear of offending either parties.

Dayuan's forces sallied out for field battle in an attempt to break the siege, but they were easily defeated by Han crossbowmen. Han engineers set to work on the river passing through Ershi and diverted it, leaving the city with no source of water as they had no wells. After a 40-day siege, the Han broke through the outer wall and captured the enemy general, Jianmi. The nobles of Ershi withdrew to the inner walls and decided to offer terms of surrender. First they killed their king, Wugua, and sent his head to Li. Then they offered Li all the horses he wanted as well as supplies in return for the army's withdrawal, but they would kill all their horses if he did not accept. Li agreed to the terms, taking some 3,000 horses as well as provisions. Before departing, Li enthroned one of the nobles called Meicai (昧蔡) as king, since he had previously shown kindness to the Han envoys.[12]

As Li set out for Dunhuang, he realized that the local areas along the way would not be able to adequately supply the army. The army separated into several groups, some taking the northern route while others the southern route. One of these groups, comprising only 1,000 or so men under the command of Wang Shensheng and Hu Chongguo, tried to take Yucheng. After several days under siege, the inhabitants of Yucheng sallied out with 3,000 men and defeated the besieging army. A few of the Han soldiers managed to escape and alert Li of the defeat. Thereupon, Li dispatched Shangguan Jie to attack Yucheng. Seeing the great host sent against him, the king of Yucheng decided to flee to Kangju, causing Yucheng to surrender shortly thereafter. When Kangju received news of Dayuan's defeat, they handed the king of Yucheng over to Shangguan, who had him executed.[12]

The army met no further opposition on the way back to Yumen Pass. Having heard of Dayuan's defeat, the rulers of the oasis states sent their kin along with the army back to the Han capital, where they presented tribute to Emperor Wu. They remained at the Han court as hostages. Despite the overall success of the second expedition, having adequate supplies and losing only a small portion of the army in battle, the entire campaign was marred by corruption and self interest. Li's soldiers, being taken from the prison population and undesirable class, were given very little care by their generals and officers, who instead abused them by withholding rations, causing desertion. As a result, Li returned with just 10,000 men and 1,000 horses fit for military service. Even so, Emperor Wu still considered these to be acceptable losses in the victory over Dayuan, and made no attempts to punish those who were responsible. Those who had survived were given handsome rewards. Li Guangli was enfeoffed as Marquis of Haixi. Zhao Di, who secured the capture of the king of Yucheng, became Marquis of Xinzhi. Shangguan Jie became privy treasurer.[12]

Aftermath

More than a year later, the nobles of Dayuan banded together and killed King Meicai, whom they considered responsible for the entire affair with the Han in the first place. Wugua's brother, Chanfeng, became the new king. Not wishing to upset the Han, Chanfeng sent his son as hostage to the Han court. In response, the Han dispatched envoys with gifts for the new ruler and made peace with Dayuan.[13]

Ten years later, Li Guangli was defeated by the Xiongnu and defected to their side. He married the Chanyu's daughter but was eventually executed over a conflict with another Han defector more favored by the Chanyu.[14]

References

- Zhao Xu (2018-05-26). "The four-footed legends of the silk road". China Daily. Retrieved 2020-04-04. Reprinted as an advertisement feature: Zhao Xu (2018-06-21). "Heavenly horses, the four-footed legends of the Silk Road". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2019-04-27. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- Benjamin 2018, pp. 72–74.

- Benjamin 2018, p. 85.

- Benjamin 2018, pp. 70–71.

- Benjamin 2018, p. 77.

- Watson 1993, pp. 244–45.

- Watson 1993, p. 244.

- Watson 1993, p. 242.

- Watson 1993, p. 246.

- Peers 1995, p. 8.

- Whiting 2002, p. 164.

- Whiting 2002, p. 165.

- Watson 1993, p. 252.

- Lin Jianming (林剑鸣) (1992). 秦漢史 [History of Qin and Han]. Wunan Publishing. pp. 557–578. ISBN 978-957-11-0574-1.

Sources

- Benjamin, Craig (2018), Empires of Ancient Eurasia: The First Silk Roads Era, 100 BCE – 250 CE, Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/9781316335567.004, ISBN 978-1-107-11496-8

- Peers, C. J. (1995), Imperial Chinese Armies (1): 200 BC – AD 589, Osprey Publishing

- Watson, Burton (1993), Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian: Han Dynasty II (Revised Edition, Columbia University Press

- Whiting, Marvin C. (2002), Imperial Chinese Military History, Writers Club Press