Han–Xiongnu War

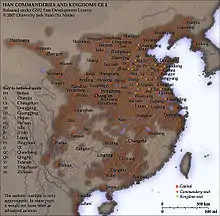

The Han–Xiongnu War,[3] also known as the Sino–Xiongnu War,[4] was a series of military battles fought between the Chinese Han Empire and the nomadic Xiongnu confederation from 133 BC to 89 AD.

| Han–Xiongnu War 漢匈戰爭 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

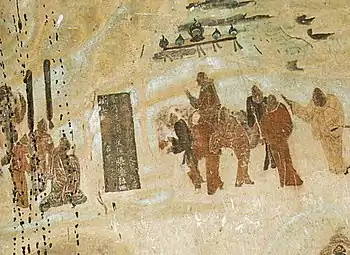

Emperor Wu dispatching the diplomat Zhang Qian to Central Asia, Mogao Caves mural, 8th century | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Xiongnu |

Han dynasty Xin dynasty (9–23 AD) Tributary and allied forces: Southern Xiongnu[1] Qiang[2] Wuhuan[2] Xianbei[2] | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Junchen Chanyu Yizhixie Chanyu Hunye King Xiutu King † Zhizhi Chanyu † ...and others |

Emperor Wu General Wei Qing General Huo Qubing General Dou Gu General Ban Chao General Dou Xian ...and others | ||||||

Starting from Emperor Wu's reign (r. 141–87 BC), the Han empire changed from a relatively passive foreign policy to an offensive strategy to deal with the increasing Xiongnu incursions on the northern frontier and also according to general imperial policy to expand the domain. In 133 BC, the conflict escalated to a full-scale war when the Xiongnu realized that the Han were about to ambush their raiders at Mayi. The Han court decided to deploy several military expeditions towards the regions situated in the Ordos Loop, Hexi Corridor and Gobi Desert in a successful attempt to conquer it and expel the Xiongnu. Hereafter, the war progressed further towards the many smaller states of the Western Regions. The nature of the battles varied through time, with many casualties during the changes of territorial possession and political control over the western states. Regional alliances also tended to shift, sometimes forcibly, when one party gained the upper hand in a certain territory over the other.

Han Empire eventually prevailed over the northern nomads, and the war allowed the Han Empire's political influence to expand deeply into Central Asia. As the situation deteriorated for the Xiongnu, civil conflicts befell and further weakened the confederation, which eventually split into two groups. The Southern Xiongnu submitted to the Han Empire, but the Northern Xiongnu continued to resist and was eventually evicted westwards by the further expeditions from Han Empire and its vassals, and the rise of Donghu states like Xianbei. Marked by significant events involving the conquests over various smaller states for control and many large-scale battles, the war resulted in the total victory of the Han empire over the Xiongnu state in 89 AD.

Background

During the Warring States period, the Qin, Zhao, and Yan states conquered various nomadic territories inhabited by the Xiongnu and other Hu peoples.[5] They strengthen their new frontiers with elongated wall fortifications.[6] By 221 BC, the Qin ended the chaotic Eastern Zhou period by conquering all other states and unifying the entire nation. In 215 BC, Qin Shi Huang ordered General Meng Tian to set out against the Xiongnu tribes, situated in the Ordos region, and establish a frontier region at the Ordos Loop.[7] Believing that the Xiongnu were a possible threat, the emperor launched a pre-emptive strike against the Xiongnu with the intention to expand his empire.[7] Later that year (215 BC), General Meng Tian succeeded in defeating the Xiongnu and driving them from the Ordos region, seizing their territory as result.[8] After the catastrophic defeat at the hands of Meng, Touman Chanyu and his followers fled far into the Mongolian Plateau.[9] Fusu (Prince of Qin) and General Meng Tian were stationed at a garrison in Suide and soon began with the construction of the walled defences, connecting it with the old walls built by Qin, Yan and Zhao states.[10] The fortified walls ran from Liaodong to Lintao, thus enclosing the conquered Ordos region,[8] safeguarding the Qin empire against the Xiongnu and other northern nomadic people.[6] Due to the northward expansion, the threat that the Qin empire posed to the Xiongnu ultimately led to the state formation of the many tribes towards a confederacy.[5]

However, after the sudden death of Qin Shi Huang, the ensuing political corruption and chaos during the short reign of Qin Er Shi would lead to various anti-Qin rebellions, eventually bringing about the collapse of the Qin Dynasty. A massive civil war then erupted between various reinstated states, with Liu Bang eventually victorious to establish the Han Dynasty. During the transitional years between Qin and Han, while the Chinese were mainly focused towards the interior of their nation, the Xiongnu took the opportunity to retake the territory north of the wall.[5] The Xiongnu frequently led incursions to the Han frontier and had considerable political influence over the border regions.[11] In response, Emperor Gaozu led a Han army against the Xiongnu in 200 BC, pursuing them as far as Pingcheng (present-day Datong, Shanxi) before being ambushed by Modu Chanyu's cavalry.[11] His encampment was encircled by the Xiongnu, but Emperor Gaozu escaped after seven days.[12] After realizing that a military solution was not feasible for the time being, Emperor Gaozu sent Liu Jing to negotiate peace with Modu Chanyu.[12] In 198 BC, a marriage alliance was concluded between the Han and the Xiongnu,[12] but this proved far from effective as the incursions in the frontier regions continued.[13][14][15]

Course

Onset

.png.webp)

By the reign of Emperor Wu, the Han empire was prospering and the national treasury had accumulated large surpluses.[16] However, burdened by the frequent Xiongnu raids at the frontier of the Han empire, the emperor abandoned the policies of his predecessors to maintain peace with the Xiongnu early in his reign.[17] In 136 BC, after continued Xiongnu incursions near the northern frontier, Emperor Wu had a court conference assembled.[18][19] The faction supporting war against the Xiongnu was able to sway the majority opinion by making a compromise for those worried about stretching financial resources on an indefinite campaign: in an engagement along the border near Mayi, Han forces would lure Junchen Chanyu over with wealth and promises of defections in order to eliminate him and cause political chaos for the Xiongnu.[18][19] Emperor Wu launched his military campaigns against the Xiongnu in 133 BC.[20][21]

In 133 BC, the Xiongnu forces led by the Chanyu[lower-alpha 1] were lured into a trap at Mayi, while a Han army of about 300,000 troops laid in ambush against the Xiongnu.[21] Wang Hui (王恢) led this campaign and commanded a force of 30,000 men strong, advancing from Dai with the intention of attacking the Xiongnu supply route.[22] Han Anguo (韓安國) and Gongsun He (公孫賀) commanded the remaining forces and advanced towards Mayi.[22] Junchen Chanyu led his army of 100,000 men towards Mayi, but he became increasingly suspicious of the situation.[22] When the ambush failed, because Junchen Chanyu realized he was about to fall into a trap and fled back north, the peace was broken and the Han court resolved to engage in full-scale war.[19][23][24] In light of this battle, the Xiongnu became aware of the Han court's intentions to go to war.[21] By that point the Han empire was long consolidated politically, militarily, and economically, and was led by an increasingly pro-war faction in the imperial court.[25]

Skirmishes at the northern frontier

In the autumn of 129 BC, a Han force of 40,000 cavalrymen launched a surprise attack against the Xiongnu in the frontier markets, where masses of Xiongnu people visited to trade.[26] In 128 BC, General Wei Qing led 30,000 men to battle at the regions north of Yanmen and came out victorious.[27] The next year (127 BC), the Xiongnu invaded Liaoxi, killing its governor, and advanced towards Yanmen.[28] Han Anguo mobilized 700 men, but was defeated and withdrew to Yuyang.[28] Thereafter, Wei Qing moved out with a force and captured some Xiongnu troops, causing the main force of the Xiongnu to withdraw.[28] Meanwhile, Li Xi had led a force across the frontier and also captured some of the Xiongnu troops.[28]

Early campaigns by the Han empire

Between 127 and 119 BC, Emperor Wu ordered the generals Wei Qing and Huo Qubing to lead several large-scale military campaigns against the Xiongnu.[21] Leading campaigns involving tens of thousands of troops, General Wei Qing captured the Ordos Desert region from the Xiongnu in 127 BC and General Huo Qubing expelled them from the Qilian Mountains in 121 BC, gaining the surrender of many Xiongnu aristocrats.[29][30] The Han court also sent expeditions, ranging to over 100,000 troops, into Mongolia in 124 BC, 123 BC, and 119 BC,[31] attacking the heart of Xiongnu territory. Following the successes of these 127–119 BC campaigns, Emperor Wu wrote edicts in which he heavily praised the two generals for their achievements.[32]

Ordos Loop

In 127 BC, General Wei Qing invaded and retook full control of the Ordos region.[33][34] Earlier that year, he had departed from Yunzhong towards Longxi to invade the Xiongnu in Ordos.[26] After the conquest, about 100,000 people resettled in the Ordos.[26] In the region, two commanderies were established, Wuyuan and Shuofang.[26][35] With the old Qin walled fortifications in their control, the Han set out to repair and extend the walls.[36] In 126 BC, the Xiongnu sent out three forces of 30,000 troops each to raid Dai, Dinxiang, and Shang.[33] In that same year (126 BC), General Wei Qing advanced from Gaoque into Mongolia with 30,000 men and inflicted defeat to the Xiongnu forces of the Tuqi King[lower-alpha 2] and captured 15,000 men along with 10 tribal chiefs.[37] In the autumn of 126 BC, the Xiongnu raided Dai once again; they took some prisoners and killed a Han military commander.[37]

Gobi Desert (south)

During the spring of 123 BC, General Wei Qing set off to Mongolia with an army to attack the Xiongnu; they marched back victorious to Dingxiang.[38] Two months later, the Han army advanced towards the Xiongnu again, but this time the Xiongnu were prepared for the invasion by the Han forces.[38] However, hereafter, due to the military expeditions that the Han empire undertook, the Xiongnu moved their capital and retreated to the far northern regions of the Gobi Desert.[38]

Hexi Corridor

In the Battle of Hexi (121 BC), the Han forces had inflicted a major defeat to the Xiongnu.[39] Emperor Wu desired to place firm control over the Hexi Corridor and decided to launch a large military offensive to purge the Xiongnu from the area.[36] The campaign was undertaken in 121 BC by General Huo Qubing.[40] Departing from Longxi that year, General Huo Qubing led light cavalry through five Xiongnu kingdoms, conquering the Yanzhi and Qilian mountain ranges from the Xiongnu.[26]

In the spring of 121 BC, Huo set out from Longxi and advanced into the territory of the Xiutu King (休屠王), beyond the Yanzhi Mountains.[41] About 18,000 Xiongnu cavalry were captured or killed.[41]

That summer (121 BC), Huo advanced into the Anshan Desert to invade the regions at the Qilian Mountains.[41] At the Qilian Mountains, the Hunye King (渾邪王) saw the deaths of over 30,000 troops in battle against the Han, while 2800 of his troops were captured.[42]

Distraught by the huge losses and fearing the wrath of the Xiongnu Chanyu, the Xiutu King and the Hunye King planned to surrender to the Han forces of General Huo Qubing.[43] However, the Xiutu King suddenly changed his mind and fled with his followers.[43] General Huo Qubing and the Hunye King gave chase and killed Xiutu and his 8000 troops.[43] In the end, the Hunye King and 40,000 Xiongnu soldiers surrendered,[26][39][42][43] which also led to the Xiongnu tribes of Hunye and Xiutu submitting to the rule of the Han empire.[44][45] Due to the series of victories, the Han had conquered a territory stretching from the Hexi Corridor to Lop Nur, thus cutting the Xiongnu off from their Qiang allies.[46] In 111 BC, a major Qiang–Xiongnu allied force was repelled from the Hexi Corridor.[47] Hereafter, four commanderies were established in the Hexi Corridor—Jiuquan, Zhangye, Dunhuang, and Wuwei—which were populated with Han settlers.[46][47]

Gobi Desert (north)

The Battle of Mobei (119 BC) saw Han forces invade the northern regions of the Gobi Desert.[39] In 119 BC, two separate expeditionary forces led by the Han generals Wei Qing and Huo Qubing mobilized towards the Xiongnu.[39][48] The two generals led the campaign to the Khangai Mountains where they forced the Chanyu to flee north of the Gobi Desert.[29][49] The two forces together comprised 100,000 cavalrymen,[50][51] 140,000 horses,[50][51] and few hundred thousand infantry.[51] They advanced into the desert in pursuit of the main force of the Xiongnu.[21] The military campaign was a major Han military victory against Xiongnu,[52] where the Xiongnu were driven from the Gobi Desert.[53] The Xiongnu casualties ranged from 80 to 90 thousand troops, while the Han casualties ranged from 20 to 30 thousand troops.[54] In the aftermath, the Han forces had lost around 100,000 horses during the campaign.[54]

During this campaign, Huo Qubing's elite troops had set off from Dai to link up with Lu Bode's forces in Yucheng, after which they advanced further and engaged the Tuqi King of the Left[lower-alpha 3] and his army.[54] Huo Qubing's army encircled and overran their enemy, killing around 70,000 Xiongnu,[39] including the Tuqi King of the Left.[55] He then went on to conduct a series of rituals upon arrival at the Khentii Mountains to symbolize the historic Han victory, then continued his pursuit as far as Lake Baikal.[56]

Wei Qing's army, setting off from Dingxiang, encountered Yizhixie Chanyu's army.[50] Wei Qing ordered his troops to arrange heavy-armoured chariots in a ring formation,[54] creating mobile fortresses that provided archers, crossbowmen, and infantry protection from the Xiongnu's cavalry charges, and allowing the Han troops to utilize their ranged weapons' advantages. A 5000-strong cavalry was deployed to reinforce the array against any Xiongnu attack.[54] The Xiongnu charged the Han forces with a 10,000-strong vanguard cavalry.[57] The battle solidified into a stalemate until dusk, when a sandstorm obscured the battlefield.[57] Subsequently, Wei Qing sent in his main forces and overwhelmed the Xiongnu.[54] The Han cavalry used the low visibility as cover and encircled the Xiongnu army from both flanks, but Yizhixie Chanyu and a contingent of troops broke through and escaped.[54]

Control over the Western Regions

With the Han conquest of the Hexi Corridor in 121 BC, the city-states at the Tarim Basin were caught in between the onslaught of the war, with much shifting of allegiance.[59] There were several Han military expeditions undertaken to secure the submission of the local kings to the Han empire; the Han took control of the regions for strategic purposes while the Xiongnu needed the regions as a source of revenue.[59][60] Due to the ensuing war with the Han empire, the Xiongnu were forced to extract more crafts and agricultural foodstuffs from the Tarim Basin urban centres.[61] By 115 BC, the Han had set up commanderies at Jiuquan and Wuwei, while extending the old Qin fortifications from Lingju to the area west of Dunhuang.[21] From 115 to 60 BC, the Han and Xiongnu competed for control and influence over these states,[62] which saw the rise of power of the Han empire over eastern Central Asia with the decline of that of the Xiongnu's.[63] The Han empire brought the states of Loulan, Jushi (Turfan), Luntai (Bügür), Dayuan (Ferghana), and Kangju (Soghdiana) into tributary submission between 108 and 101 BC.[64][65] The long-walled defence line that now stretched all the way to Dunhuang protected the people, guided caravans and troops to and from Central Asia, and served to separate the Xiongnu from their allies, the Qiang people.[66]

In 115 BC Zhang Qian was once again dispatched to the Western Regions to secure military alliances against the Xiongnu.[67][68] He sought out the various states in Central Asia, such as the Wusun.[67] He came back without achieving his goals, but he gained valuable knowledge about the Western Regions like in his previous travels.[68] Emperor Wu received reports from Zhang about the large and powerful horses of Ferghana.[69] These horses were known as "heavenly horses"[69][70] or "blood-sweating horses".[70] Zhang brought back some of these horses to the Han empire.[68] The emperor thought that the horses were of high importance to fight the Xiongnu.[70] The refusal of the Dayuan kingdom, a nation centred in Ferghana, to provide the Han empire with the horses and the execution of a Han envoy led to conflict;[71] the Han forces brought Dayuan into submission in 101 BC.[67][72] The Xiongnu, aware of this predicament, had tried to halt the Han advance, but they were outnumbered and suffered defeat.[73]

General Zhao Ponu (趙破奴) was sent on an expedition in 108 BC to invade Jushi (Turfan), a critical economic and military stronghold of the Xiongnu in the Western Regions.[73] After he conquered the region, the Han forces repelled all Xiongnu attacks to regain control over Jushi.[73] When King Angui acceded the throne of Loulan, the kingdom—which was the easternmost state of the Western Regions—became increasingly apprehensive towards the Han.[74] Their policies became somewhat anti-Han in nature and supportive towards the Xiongnu, such as allowing the killing of passing Han envoys to happen and revealing Han military logistics.[74][75] In 77 BC, King Angui received the Han emissary Fu Jiezi and held a banquet for the envoy, who came under the guise of bringing many coveted gifts.[74] During the banquet, Fu Jiezi requested a private discussion with King Angui, which was a pretence for the assassination of the Loulan ruler by two of Fu Jiezi's officers.[74] Amid the cries of horror, Fu Jiezi proclaimed an admonition[lower-alpha 4] to the Loulan aristocracy and beheaded the dead king.[74] The Han court informed Weituqi—who was an ally of the Han—of his brother's death, had him escorted back from Chang'an to Loulan, and installed him as the new monarch of the kingdom, which was renamed Shanshan.[74][76] Thereafter, the royal seat was relocated to the southern parts of Shanshan (present-day Kargilik or Ruoqiang), outside the sphere of Xiongnu influence.[75]

The Xiongnu practised marriage alliances with Han dynasty officers and officials who defected to their side. The older sister of the Chanyu (the Xiongnu ruler) was married to the Xiongnu General Zhao Xin, the Marquis of Xi who was serving the Han dynasty. The daughter of the Chanyu was married to the Han Chinese General Li Ling after he surrendered and defected.[77][78] The Yenisei Kirghiz Khagans claimed descent from Li Ling. Another Han Chinese General who defected to the Xiongnu was Li Guangli who also married a daughter of the Chanyu.

Decline of the Xiongnu

Due to the many losses inflicted on the Xiongnu, rebellion soon broke out and former enslaved people rose up in arms.[79] Around 80 BC, the Xiongnu attacked the Wusun in a punitive campaign and soon the Wusun monarch requested military support from the Han empire.[80] In 72 BC, the joint forces of the Wusun and Han invaded the territory of the Luli King[lower-alpha 5] of the Right.[79] Around 40,000 Xiongnu people and many of their livestock were captured before their city was sacked after the battle.[79] The very next year, various tribes invaded and raided the Xiongnu territory from all fronts; Wusun from the west, Dingling from the north, and Wuhuan from the east.[79] The Han forces had set out in five columns and invaded from the south. According to Hanshu, this event marks the beginning of Xiongnu decline and the dismantlement of the confederation.

Internal discord between the Xiongnu

As the Xiongnu economic and military situation deteriorated, the Xiongnu were willing to renew peace during the reigns of Huyandi Chanyu (r. 85–69 BC) and Xulüquanqu Chanyu (r. 68–60 BC), but the Han court gave only one option, tributary submission.[81] After Xulüquanqu Chanyu's death in 60 BC,[82] a Xiongnu civil war broke loose in 57 BC over the succession, which fully fragmented the Xiongnu confederation with many contenders.[83] In the end, only Zhizhi Chanyu and Huhanye Chanyu survived the struggle to power.[84] After Zhizhi Chanyu (r. 56–36 BC) had inflicted serious losses against his rival Huhanye Chanyu (r. 58–31 BC), Huhanye and his supporters debated whether to request military protection and become a Han vassal.[85] In 53 BC, Huhanye decided to do so and surrendered to the reign of the Han empire.[85][86][87]

General Chen Tang and Protector General Gan Yanshou, acting without explicit permission from the Han court, killed Zhizhi Chanyu at his capital city (present-day Taraz, Kazakhstan) in 36 BC.[88][89] Taking the initiative, Chen Tang had forged an imperial decree, which led to the mobilization of 40,000 troops in two columns.[90] The Han forces besieged and defeated the forces of Zhizhi Chanyu, and afterwards beheaded him.[90] His head was sent to the Han capital Chang'an.[91] On return to Chang'an, the two officers faced legal enquiries for forging a decree, but were pardoned.[92] Chen and Gan received modest rewards, although the Han court was reluctant to do so due to the precedent that this event set.[88][89]

Collapse of power

In 9 AD, the Han official Wang Mang usurped the Han throne and proclaimed a new Chinese dynasty, known as Xin.[93] He regarded the Xiongnu as lowly vassals and relations rapidly deteriorated.[94][93] During the winter 10 to 11 AD, Wang amassed 300,000 troops along the northern frontier, which forced the Xiongnu to back down from launching large-scale attacks.[94][95] Although Han rule was restored in August 25 AD by Emperor Guangwu,[96] its grip over the Tarim Basin had weakened.[97] The Xiongnu had namely taken advantage of the situation and gained control over the Western Regions.[98][99]

The first half of the 1st century BC witnessed several succession crises for the Xiongnu leadership, allowing the Han empire to reaffirm its control over the Western Regions.[100][101] Huduershi Chanyu was succeeded by his son Punu (蒲奴) in 46 AD, thus breaking the late Huhanye's orders that only a Xiongnu ruler's brother was a valid successor.[102] Bi (比), the Rizhu King of the Right and Huduershi's nephew, was outraged and was declared a rival Chanyu by eight southern Xiongnu tribes in 48 AD.[102] The Xiongnu confederation fell apart in the Northern Xiongnu and Southern Xiongnu, and Bi submitted to the reign of the Han empire in 50 AD.[102] The Han took control of the Southern Xiongnu under Bi, which had 30–40 thousand troops and a population of roughly twice or thrice the size.[103]

Between 73 and 102 AD, General Ban Chao led several expeditions in the Tarim Basin, re-establishing Han control over the region.[98] At the capital of Shanshan by Lop Nur, Ban Chao and a small party of his men slaughtered a visiting Northern Xiongu embassy to Shanshan.[104] Ban Chao presented their heads to King Guang of Shanshan, who was overwhelmed by the ordeal, whereupon he sent hostages to Han.[104] When Ban Chao traveled further to Yutian (Khotan), King Guangde received him with little courtesy.[104] The king's soothsayer told the king that he should demand Ban Chao's horse, so Ban Chao killed the soothsayer for the insult.[104] Impressed by the ruthlessness that he witnessed, the king killed a Xiongnu agent and offered submission to Han.[104] Going further westward, Ban Chao and his party arrived at Shule.[104] Earlier, King Jian of Qiuci had deposed the former king and replaced him with his officer Douti.[104] In 74 AD, Ban Chao's forces captured King Douti of Kashgar (Shule 疏勒), both a puppet of Kucha (Qiuci 龜玆) and an ally of the Xiongnu.[105] Local opponents to the new regime had offered support to the Han.[104] Tian Lü (Ban Chao's officer) took Douti captive and Ban Chao put Zhong (a prince of the native dynasty) on the throne.[104] Ban Chao, insisting on leniency, send Douti back to Qiuci unharmed.[104]

In 73 AD, General Dou Gu and his army departed from Jiuquan and advanced towards the Northern Xiongnu, defeating the Northern Xiongnu and pursuing them as far as Lake Barkol before establishing a garrison at Hami.[106] In 74 AD, Dou Gu retook Turfan from the Xiongnu.[106] The Han campaigns resulted in the retreat of the Northern Xiongnu to Dzungaria, while Ban Chao was threatening and bringing the city-states at the Tarim Basin to submission under the Han empire once again.[98] In 74 AD, the King of Jushi submitted to the Han forces under General Dou Gu as the Xiongnu were unable to engage the Han forces.[105]

Later in the year (74 AD), the kingdoms of Karasahr (Yanqi 焉耆) and Kucha were forced to surrender to the Han empire.[105] Although Dou Gu was able to evict the Xiongnu from Turfan in 74 AD, the Northern Xiongnu soon invaded the Bogda Mountains while their allies from Karasahr and Kucha killed the Protector General Chen Mu and his men.[107] As a result, the Han garrison at Hami was forced to withdraw in 77 AD, which was not reestablished until 91 AD.[107][108]

Final stages

In 89 AD, General Dou Xian led a Han expedition against the Northern Xiongnu.[109][110] The army advanced from Jilu, Manyi, and Guyang in three great columns. In the summer of 89, the forces—comprising a total of 40,000 troops—assembled at Zhuoye Mountain.[111] Near the end of the campaign, Dou's forces chased the Northern Chanyu into the Altai Mountains, killing 13,000 Xiongnu and accepting the surrender of 200,000 Xiongnu from 81 tribes.[109][110] A light cavalry of 2000 was sent towards the Xiongnu at Hami, capturing the region from them.[109] General Dou Xian marched with his troops in a triumphal progress to the heartland of the Northern Xiongnu's territory and engraved an inscription commemorating the victory on Mount Yanran, before returning to Han.[111] The Han victory in the campaign of 89 AD resulted in the destruction of the Xiongnu state.[112] In 2017, a joint Sino-Mongolian archaeological expedition rediscovered the Inscription of Yanran in the Khangai Mountains of central Mongolia.[113]

Aftermath

In 90 AD, General Dou Xian had encamped at Wuwei.[3] He sent Deputy Colonel Yan Pan with 2000 light cavalry to strike down the final Xiongnu defenses in the Western Regions, capturing Yiwu and receiving the surrender of Jushi.[3] Major Liang Feng was dispatched to capture the Northern Chanyu, which he did, but he was forced to leave him behind as Dou Xian had already broken camp and returned to China.[3] In the tenth month of 90 AD, Dou Xian sent Liang Feng and Ban Gu to help the Northern Chanyu make preparations for his planned travel as he wished to submit to the Han court in person the following month.[114]

However, this never came to be as Dou Xian dispatched General Geng Kui and Shizi of the Southern Xiongnu with 8000 light cavalry to attack the Northern Chanyu, encamped at Heyun (河雲), in 90 AD.[114] Once the Han forces arrived at Zhuoye Mountains, they left their heavy equipment behind to launch a swift pincer movement towards Heyun.[114] Geng Kui attacked from the east via the Khangai Mountains and Ganwei River (甘微河), while Shizi attacked from the west via the Western Lake (西海).[114] The Northern Chanyu—said to be greatly shocked by this—launched a counterattack, but he was forced to flee as he left his family and seal behind.[114] The Han killed 8000 men and captured several thousands.[114] In 91 AD, General Geng Kui and Major Ren Shang with a light cavalry of 800 advanced further via the Juyan Gol (Juyansai) into the Altai Mountains, where the Northern Chanyu had encamped.[114] At the Battle of Altai Mountains, they massacred 5000 Xiongnu men and pursued the Northern Chanyu until he escaped to an unknown place.[114] By 91 AD, the last remnants of the Northern Xiongnu had migrated west towards the Ili River valley.[115]

The Southern Xiongnu—who had been situated in the Ordos region since about 50 AD—remained within the territory of the Han empire as semi-independent tributaries.[116] They were dependent to the Han empire for their livelihood as indicated by a memorial[lower-alpha 6] from the Southern Chanyu to the Han court in 88 AD.[117] Following the military successes against the Xiongnu, General Ban Chao was promoted to the position of Protector General and stationed in Kucha in 91 AD.[118] At the remote frontier, Ban Chao reaffirmed absolute Han control over the Western Regions from 91 AD onwards.[109]

Impact

Military

Chao Cuo was one of the first known ministers to suggest to Emperor Wen that Han armies should have a cavalry-centric army to counter the nomadic Xiongnu to the north, since Han armies were still primarily infantry with cavalries and chariots playing a supporting role.[119] He advocated the policy of "using barbarians to attack barbarians", that is, incorporating surrendered Xiongnu and other nomadic tribes into the Han military, a suggestion that was eventually adopted, especially with the establishment of dependent states of different nomads living on the Han empire's frontiers.[120]

In a memorandum entitled Guard the Frontiers and Protect the Borders that he presented to the throne in 169 BC, Chao compared the relative strengths of Xiongnu and Han battle tactics.[121] In regards to the Han armies, Chao deemed the Xiongnu horsemen better prepared for rough terrain due to their better horses, better with horseback archery, and better able to withstand the elements and harsh climates.[122][123] However, on level plains, he regarded Xiongnu cavalry inferior especially when faced with Han shock cavalry and chariots as the Xiongnu are easily dispersed.[122] He emphasized that the Xiongnu were incapable of countering the superior equipment and weaponry.[122] He also noted that in contrast the Han armies were better capable to fight in disciplined formations.[122] According to Chao, the Xiongnu were also defenseless against coordinated onslaughts of arrows—especially long-ranged and in unison—due to their inferior leather armour and wooden shields.[122][123] When dismounted in close combat, he believed that the Xiongnu, lacking the ability as infantry, would be decimated by Han soldiers.[122][123]

During Emperor Jing's reign, the Han court initiated breeding programs for military horses and established 36 large government pastures in the border regions, extending from Liaodong to Beidi.[124] In preparation for the military use of the horses, the best breeds were selected to partake military training.[124] The Xiongnu frequently raided the Han government pastures, because the military horses were of great strategic importance for the Han military against them.[124] By the time of Emperor Wu's reign, the horses amounted to well over 450,000.[124]

At the start of Emperor Wu's reign, the Han empire had a standing army comprising 400,000 troops, which included 80,000 to 100,000 cavalrymen, essential to the future campaigns against the Xiongnu.[125] However, by 124 BC, that number had grown to a total of 600,000 to 700,000 troops, including 200,000 to 250,000 cavalrymen.[125] In order to sustain the military expeditions against the Xiongnu and its resulting conquests, Emperor Wu and his economic advisors undertook many economic and financial reforms, which proved to be highly successful.[125]

In 14 AD, Yan Yu presented the difficulties of conducting extended military campaigns against the Xiongnu.[62] For a 300-day campaign, each Han soldier needed 360 liters of dried grain.[62] These heavy supplies had to be carried by oxen, but experience showed that an ox could only survive for about 100 days in the desert.[62] Once in the territory of the Xiongnu, the harsh weather would also prove to be very inhospitable for the Han soldiers, who could not carry enough fuel for the winter.[62] For these reasons, according to Yan Yu, military expeditions seldom lasted longer than 100 days.[62]

For their western campaigns against the Xiongnu, the Han armies exacted their food supplies from the Western Regions.[126] This placed a heavy burden to the western states, thus the Han court decided to initiate agricultural garrisons in Bugur and Kurla.[126] During Emperor Zhao's reign (r. 87–74 BC), the agricultural garrison in Bugur was expanded to accommodate the heavy Han military presence which was the natural result of the empire's westward expansion.[126] During Emperor Xuan's reign (r. 74–49 BC), the farming soldiers in Kurla were increased to 1500 under Protector-General Zheng Ji's administration in order to support the military expeditions against the Xiongnu in Turfan.[126] Immediately after the Han conquest of Turfan, Zheng established an agricultural garrison in Turfan.[126] Even though, the Xiongnu unsuccessfully tried to prevent the Han from making Turfan into a major economic base by military force and threats.[126]

Diplomacy

In 162 BC, the Xiongnu troops of Laoshang Chanyu had invaded and driven the Yuezhi from their homeland; the Chanyu had the Yuezhi monarch executed and his skull fashioned into a drinking cup.[60][127] Thus the Han court decided it was favourable to send an envoy to the Yuezhi to secure a military alliance.[128] In 138 BC, the diplomat Zhang Qian left with an envoy and headed towards the Yuezhi encampments.[60][129] However, the envoy was captured by the Xiongnu and held hostage.[60][128] A decade went by, until Zhang Qian and some of his convoy escaped.[60][128] They travelled to the territories of Ferghana (Dayuan 大宛), Soghdiana (Kangju 康居), and Bactria (Daxia 大夏), ultimately finding the Yuezhi forces north of the Amu River.[128] Despite their efforts, the envoy could not secure a military alliance.[69][128] As the Yuezhi had settled in those new lands for quite some time, they had almost no desire to wage a war against the Xiongnu.[69][128] In 126 BC, Zhang Qian headed to the Hexi Corridor in order to return to his nation.[33] While traveling through the area, he was captured by the Xiongnu, only to escape a year later and return to China in 125 BC.[48]

The Xiongnu attempted to negotiate peace several times, but every time the Han court would accept nothing less than tributary submission of the Xiongnu.[130] Tributary relations with the Han comprised out of several things.[131] Firstly, the Chanyu or his representative was required to come pay homage to the Han court.[131] Secondly the heir apparent or a prince needed to be delivered to the Han court as hostage.[131] Thirdly, the Chanyu had to present tribute to the Han emperor and in return will receive imperial gifts.[131] Accepting the tributary system meant that the Xiongnu were lowered to the status of outer vassal, while the marriage alliance meant that the two nations were regarded as equal states.[131][132] In 119 BC, Yizhixie Chanyu (126–114) sent an envoy, hoping to achieve peaceful relations with the Han.[130] However, the peace negotiations collapsed, since the Han court disregarded his terms and gave him the option to become an outer vassal instead, which infuriated Yizhixie Chanyu.[130] In 107 BC, Wuwei Chanyu (114–105) also attempted to negotiate peaceful relations and even halted the border raids.[130] In response, the Han disregarded his terms and demanded that the Chanyu sent his heir apparent as a hostage to Chang'an, which once again led to the breakdown of the peace negotiations.[130]

In 53 BC, Huhanye Chanyu decided to submit to the Han court.[131] He sent his son Zhulouqutang (朱鏤蕖堂), the Tuqi King of the Right, as hostage to the Han court in 53 BC.[131] In 52 BC, he formally requested through the officials at the Wuyuan commandary to have an audience with the Han court to pay homage.[131] Thus, the next year (51 BC), he arrived at court and personally paid homage to Emperor Xuan during the Chinese New Year.[131] In 49 BC, he traveled to the Han court for a second time to pay homage to the emperor.[117] In 53 BC, Zhizhi Chanyu also sent his son as hostage to the Han court.[133] In 51 and 50 BC, he sent two envoys respectively to Han to present tribute, but failed to personally come to the Han court to pay homage.[133] Therefore, he was rejected by the Han court, leading to the execution of a Han envoy in 45 BC.[134] In 33 BC, Huhanye Chanyu came to the Han court to pay homage again.[133] During his visit, he asked to become an imperial son-in-law.[133] Instead of granting him this request, Emperor Yuan decided to give him a court lady-in-waiting.[133] Thus, the Han court allowed Huhanye Chanyu to marry Lady Wang Zhaojun.[133][134] Yituzhiyashi (伊屠智牙師), the son of Huhanye and Wang Zhaojun, became a vocal partisan for the Han empire within the Xiongnu realm.[135] Although peaceful relations were momentarily achieved, it fully collapsed when the Han official Wang Mang came to power.[103][136]

When Bi, the Southern Chanyu, decided submit to the Han in 50 AD, he sent a princely son as hostage to the Han court and prostrated to the Han envoy as he received the imperial edict from them.[137] During the Eastern Han period, the tributary system had made some significant changes, which placed the Southern Xiongnu more tightly under regulation and supervision of the Han.[137] The Chanyu was required to send tribute and a princely hostage annually, while an imperial messenger would be dispatched to escort the previous princely hostage back.[138] The Southern Xiongnu were resettled inside the empire at the northern commanderies and were overseen by a Han prefect, who acted as an arbiter in their legal cases and monitored their movements.[139] Attempts by Punu, the Northern Chanyu, to establish peaceful relations with the Han empire always failed, because the Northern Xiongnu were unwilling to come under Han's tributary system and the Han court had no interest to treat them along the same lines as the Southern Xiongnu instead of dividing them.[140]

Geography

In 169 BC, the Han minister Chao Cuo presented to Emperor Wen a memorandum on frontier defence and the importance of agriculture.[141] Chao characterized the Xiongnu as people whose livelihood did not depend on permanent settlement and were always migrating.[142] As such, he wrote, the Xiongnu could observe the Han frontier and attack when there were too few troops stationed in a certain region.[142] He noted that if troops are mobilized in support, then few troops will be insufficient to defeat the Xiongnu, while many troops will arrive too late as the Xiongnu will have retreated by then.[142] He also noted that keeping the Xiongnu mobilized will be at a great expense, while they will just raid another time after dispersing them.[142] To negate these difficulties, Chao Cuo elaborated a proposal, which in essence suggested that military-agricultural settlements with permanent residents should be established to secure the frontier and that surrendered tribes should serve along the frontier against the Xiongnu.[142]

When Emperor Wu made the decision to conquer the Hexi Corridor, he had the intention to separate the Xiongnu from the Western Regions and from the Qiang people.[143] In 88 BC, the Xianling tribe of the Qiang people sent an envoy to the Xiongnu, proposing a joint-attack against the Han in the region as they were discontented that they had lost the fertile lands at Jiuquan and Zhangye.[143] It had often been the meeting place between the Xiongnu and the Qiang before the Han empire had conquered and annexed the Hexi Corridor.[143] In 6 BC, Wang Shun (王舜) and Liu Xin noted that the frontier commandaries of Jiuquan, Zhangye, and Dunhuang were established by Emperor Wu to separate the then-powerful Chuoqiang tribe of the Qiang people from the Xiongnu.[143] The Chuoqiang tribe and its king, however, eventually submitted to the Han empire and took part in the campaigns against the Xiongnu.[144]

In 119 BC, when the Xiongnu suffered a catastrophic defeat by the Han armies, the Chanyu moved his court (located in present-day Inner Mongolia) to another location north.[145][146] This had the desired result that the Xiongnu were separated from the Wuhuan people, which also prevented the Xiongnu from exacting many resources from the Wuhuan.[145] The Han court placed the Wuhuan in tributary protection and resettled them in five northeastern commandaries, namely Shanggu, Yuyang, Youbeiping (present-day Hebei), Liaoxi, and Liaodong (present-day Liaoning).[147] A new office, the Colonel-Protector of the Wuhuan, was established in Shanggu in order to prevent contact between the Wuhuan with the Xiongnu and to use them to monitor the Xiongnu activities.[147] Nevertheless, the effective Han control over the Wuhuan was lacking through much of the Western Han period, since the Xiongnu had considerable military and political influence over the Wuhuan while relations between the Wuhuan and Han often remained strained at best.[148] This can be exemplified by a situation in 78 BC, when the Xiongnu led a punitive campaign against the Wuhuan, resulting in General Fan Mingyou (范明友) leading a Han army to impede further incursions.[149] When they learned that the Xiongnu had left by the time the army arrived, the Han court ordered Fan to attack the Wuhuan instead, killing 6000 Wuhuan men and three chieftains, since the Wuhuan had recently raided Han territory.[149] Only in 49 AD, when 922 Wuhuan chieftains submitted during Emperor Guangwu's reign, did many of the Wuhuan tribes come under tributary system of the Han empire.[150] The Han court provided for the Wuhuan and in return the Wuhuan tribes guarded the Han frontier against the Xiongnu and other nomadic peoples.[150][151]

When the Hunye King surrendered to the Han in 121 BC, the Han court resettled all the 40,000 Xiongnu people from the Hexi Corridor into the northern frontier regions.[152] The Hexi Corridor proved to be an invaluable region, since it gave direct access and became the base of military operations into the Western Regions[46] Possession of the Western Regions was economically critical to the Xiongnu, since they exacted many of their necessary resources from the western states.[153] The diplomat Zhang Qian suggested to the emperor to establish diplomatic relations with the western states.[154] He proposed to try convince the Wusun in reoccupying their former territory in the Hexi Corridor and to form an alliance with them against the Xiongnu.[154] In 115 BC, Zhang Qian and his men were sent towards the Western Regions, but they did not succeed in convincing the Wusun to relocate.[155] They were, however, successful in establishing contact with the many states, such as Wusun, Dayuan (Ferghana), Kangju (Soghdiana), Daxia (Bactria), and Yutian (Khotan).[155] Although the Han empire tried to diplomatically sway the western states over the years, it met with little success due to the Xiongnu's influence over the Western Regions at the time.[156] Therefore, from 108 BC onwards, the Han resorted to conquest in order to bring the western states to submission.[157]

Since Loulan (Cherchen) was the closest western state to Han, it was key for the Han empire's expansion into Central Asia.[158] Turfan (Jushi), on the other hand, was the Xiongnu's entrance into the Western Regions.[159] By conquering Loulan and Turfan, the Han empire would gain two critical locations in the Western Regions, achieving direct access to the Wusun in the Ili River valley and Dayuan (Ferghana) between Syr and Amu Darya.[158] This happened in 108 BC, when General Zhao Ponu conquered these two states.[158] The farthest-reaching invasion was Li Guangli's campaign against Ferghana.[65] If the Han armies succeeded in conquering Ferghana, the Han empire would demonstrate certain military might to the western states and consolidate its control, while gaining many of the famed Ferghana horses.[158] The Xiongnu were aware of the situation and attempted to stop the invasion, but they were defeated by Li Guangli's forces.[158] After a campaign that lasted four years, Li Guangli conquered Ferghana in 101 BC.[158]

The control over Turfan, however, often fluctuated due to its proximity to the Xiongnu.[160] In 90 BC, General Cheng Wan (成娩) led the troops of six western states against Turfan to prevent it from allying the Xiongnu.[160] The fact that the forces used comprised solely from the troops of the western states was, as Lewis (2007) remarked, a clear indication of the political influence that the Han empire had over the region.[161] Cheng was a former Xiongnu king himself, but he had submitted to the Han and was ennobled as Marquis of Kailing (開陵侯).[160] As a result of the expedition, the Han court received the formal submission of Turfan later in the year (90 BC).[160] This victory was significant in the sense that Turfan's location was the closest to the Xiongnu of all the western states, thereby they lost their access into the Western Regions with this Han conquest.[161]

In 67 BC, the Han empire gained absolute control over the Turfan Depression after inflicting a significant defeat to the Xiongnu.[160] During the former Xiongnu rule of the Western Regions, the area was under the jurisdiction of the Rizhu King (日逐王) with the office "Commandant in Charge of Slaves".[162] However, in 60 BC, the Rizhu King surrendered to Protector General Zheng Ji.[162] Afterwards (60 BC), the Han imperial court established the Protectorate of the Western Regions.[67][160][163] The Han empire, now in absolute control of the Western Regions, placed it under the jurisdiction of its Protector General.[164][165] As its dominance of the area was established, the Han were effectively controlling the trade and shaping the early history of what would be known as the Silk Road.[67]

In 25 AD, Liu Xiu was established as Emperor Guangwu, restoring the Han throne after a usurpation by the Han official Wang Mang, thus initiating the Eastern Han period.[95] During his reign, the Han empire began to abandon its offensive strategy against the Xiongnu, which allowed the latter to frequently raid the northern frontier.[166] It resulted in large migrations southwards, which led to the depopulation of the frontier regions.[166] During the Eastern Han period, various nomadic peoples were resettled in these frontier regions, serving the Han empire as cavalry against the Xiongnu.[166] With his primary focus still towards the interior of the empire, Emperor Guangwu declined several requests from the western states to re-establish the office of Protector-General of the Western Regions.[167] Early in Emperor Guangwu's reign, King Kang of Yarkand united neighbouring kingdoms to resist the Xiongnu.[168] At the same time, he protected the Han officials and people of the former Protector-General, who were still left behind after Wang Mang's reign.[168] In 61 AD, Yarkand was conquered by Khotan and the western states fell in conflict with each other.[168] Taking this opportunity, the Northern Xiongnu recovered their control over the Western Regions, which threatened the security of the Hexi Corridor.[168] In 73 AD, General Dou Gu was sent on a punitive expedition to the Xiongnu and inflicted them a considerable defeat.[106] Immediately, the fertile lands of Hami (Yiwu) was reoccupied and an agricultural garrison established.[106] The next year (74 AD), he expelled the Xiongnu from Turfan and reoccupied the state.[106] The recovery of Hami and Turfan facilitated the re-establishment of the Protector-General, since these important locations were key points to control the Western Regions.[106]

See also

- Book of Han, a classical historiographical work covering the early history of the Han empire

- Han–Nanyue War, a military campaign launched by Emperor Wu against Nanyue

- Gojoseon–Han War, a military campaign launched by Emperor Wu against Gojoseon

- The Emperor in Han Dynasty, a 2005 Chinese television series based on the life story of Emperor Wu

- Li Ling, a Han military leader and defector to the Xiongnu

- Records of the Grand Historian, a classical historiographical work written in this era

- Sima Qian, author of the Records of the Grand Historian who was punished for defending Li Ling

- Su Wu, a Han statesman and diplomat who was a captive of the Xiongnu for about two decades

Notes

- In the Xiongnu hierarchy, the Chanyu was the supreme leader (Lewis 2007, 131).

- Second to the Chanyu in power were the Tuqi Kings; the Tuqi Kings are also called the "Wise Kings", where the Xiongnu word for "Tuqi" means "Wise" (Lewis 2007, 131).

- The Tuqi King of the Left was generally designated as the successor of the Chanyu (Lewis 2007, 131).

- The translation given by Hulsewé (1979, 90) is as follows: "The Son of Heaven has sent me to punish the king, by reason of his crime in turning against Han. It is fitting that in his place you should enthrone his younger brother Wei-t'u-ch'i who is at present in Han. Han troops are about to arrive here; do not dare to make any move which would result in yourselves bringing about the destruction of your state."

- Second to the Chanyu in power were the Tuqi Kings, followed by the Luli Kings (Lewis 2007, 131).

- The translation given by Lewis (2007, 137) states: "Your servant humbly thinks back on how since his ancestor submitted to the Han we have been blessed with your support, keeping a sharp watch on the passes and providing strong armies for more than forty years. Your subjects have been born and reared in Han territory and have depended entirely on the Han for food. Each year we received gifts counted in the hundreds of millions [of cash]."

References

- Graff 2002, pp. 39, 40.

- Graff 2002, p. 40.

- Wu 2013, 71.

- Nara Shiruku Rōdo-haku Kinen Kokusai Kōryū Zaidan; Shiruku Rōdo-gaku Kenkyū Sentā (2007). Opening up the Silk Road: the Han and the Eurasian world. Nara International Foundation Commemorating the Silk Road Exposition. p. 23. ISBN 978-4-916071-61-3. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- Cosmo 1999, 892–893.

- Lewis 2007, 59.

- Cosmo 1999, 964.

- Beckwith 2009, 71.

- Beckwith 2009, 71–72.

- Cheng 2005, 15.

- Yü 1986, 385–386.

- Yü 1986, 386.

- Yü 1986, 388.

- Lewis 2007, 132–136.

- Chang 2007a, 152.

- Guo 2002, 180.

- Lewis 2000, 43.

- Cosmo 2002, 211–214.

- Yü 1986, 389–390.

- Barfield 2001, 25.

- Guo 2002, 185.

- Whiting 2002, 146.

- Cosmo 2002, 214.

- Torday 1997, 91–92.

- Chang 2007a, 159.

- Yü 1986, 390.

- Whiting 2002, 147.

- Whiting 2002, 148.

- Yü 1986, 390.

- Cosmo 2002, 237–239.

- Gernet 1996, 120.

- Chang 2007a, 189.

- Whiting 2002, 149.

- Lovell 2006, 71.

- Loewe 2009, 69–70.

- Yamashita & Lindesay 2007, 153–154.

- Whiting 2002, 151.

- Whiting 2002, 151–152.

- Tucker et al. 2010, 109.

- Chang 2007a, 5.

- Whiting 2002, 152–153.

- Deng 2007, 53–54.

- Chang 2007a, 201.

- Whiting 2002, 153.

- Barfield 1981, 50.

- Yü 1986, 391.

- Chang 2007b, 8.

- Christian 1998, 196.

- Cosmo 2002, 240.

- Whiting 2002, 154.

- Chang 1966, 158.

- Loewe 2009, 72.

- Barfield 1981, 58.

- Whiting 2002, 154–155.

- Chang 1966, 161.

- Sima & Watson, 1993.

- Whiting 2002, 155.

- Honour, Hugh; Fleming, John (2005). A world history of art (7th ed.). London: Laurence King. p. 257. ISBN 9781856694513.

- Millward 2006, 21.

- Golden 2011, 29.

- Cosmo 2002, 250–251.

- Yü 1986, 390–391.

- Lewis 2007, 137–138.

- Chang 2007b, 174.

- Yü 1986, 409–411.

- Loewe 2009, 71.

- Golden 2011, 30.

- Haar 2009, 75.

- Lovell 2006, 73.

- Golden 2011, 29–30.

- Boulnois 2004, 82.

- Millward 1998, 25.

- Yü 1994, 132.

- Hulsewé 1979, 89–91.

- Baumer 2003, 134.

- Chang 2007a, 225.

- Cosmo, Nicola Di. "Aristocratic elites in the Xiongnu empire": 161. Retrieved 2019-01-11. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Monumenta Serica, Volume 52 2004, p. 81.

- Yü 1994, 135.

- Zadneprovskiy 1999, 460.

- Yü 2002, 138.

- Barfield 1981, 51.

- Lewis 2007, 137.

- Spakowski 1999, 216.

- Yü 1986, 394–395.

- Psarras 2004, 82.

- Grousset 2002, 37–38

- Yü 1986, 396–398.

- Loewe 1986, 211–213.

- Whiting 2002, 179.

- Yü 1986, 396.

- Loewe 2006, 60.

- Higham 2004, 368.

- Bielenstein 1986, 237.

- Tanner 2009, 110.

- Tanner 2009, 112.

- Millward 2006, 22–23.

- Millward 2006, 23–24.

- Yü 1986, 399.

- Loewe 1986, 196–198.

- Yü 1986, 392–394.

- Yü 1986, 399–400.

- Christian 1998, 202.

- Crespigny 2007, 4–6

- Whiting 2002, 195.

- Yü 1986, 414–415.

- Crespigny 2007, 73.

- Yü 1986, 415 & 420.

- Yü 1986, 415.

- Crespigny 2007, 171.

- Crespigny 2009, 101.

- Lewis 2007, 138.

- Chen, Laurie (21 August 2017). "Archaeologists discover story of China's ancient military might carved in cliff face". South China Morning Post.

- Wu 2013, 71–72.

- Yü 1986, 405.

- Tanner 2009, 116.

- Lewis 2007, 137.

- Wintle 2002, 99.

- Cosmo 2002, 203–204.

- Yü 1967, 14.

- Chang 2007b, 18.

- Lewis 2000, 46–47.

- Cosmo 2002, 203.

- Chang 2007a, 151–152.

- Chang 2007a, 86–88.

- Yü 1986, 419.

- Yü 1994, 127.

- Millward 2006, 20.

- Lewis 2007, 21.

- Yü 1986, 394.

- Yü 1986, 395.

- Chang 2007a, 140–141.

- Yü 1986, 398.

- Christian 1998, 201.

- Bielenstein 1986, 236.

- Yü 1986, 398–399.

- Yü 1986, 400.

- Yü 1986, 400–401.

- Yü 1986, 401.

- Yü 1986, 403–404.

- Chang 2007a, 147.

- Lewis 2000, 46–48.

- Yü 1986, 424.

- Yü 1986, 424–425.

- Yü 1986, 436–437.

- Lewis 2007, 149.

- Yü 1986, 437.

- Yü 1986, 437–438.

- Yü 1986, 438.

- Yü 1986, 438–439.

- Lewis 2007, 150.

- Yü 1986, 407.

- Lewis 2007, 140.

- Yü 1986, 407–408.

- Yü 1986, 408.

- Yü 1986, 408–409.

- Yü 1986, 409.

- Yü 1986, 409–410.

- Yü 1986, 409 & 415.

- Yü 1986, 410–411.

- Lewis 2007, 145.

- Yü 1986, 411.

- Bowman 2000, 12.

- Millward 2006, 22.

- Chang 2007a, 229.

- Lewis 2007, 25.

- Yü 1986, 413.

- Yü 1986, 414.

Bibliography

- Barfield, Thomas J. (1981). "The Hsiung-nu Imperial Confederacy: Organization and Foreign Policy". The Journal of Asian Studies. 41 (1). doi:10.2307/2055601. JSTOR 2055601.

- Barfield, Thomas J. (2001). "The Shadow Empires: Imperial State Formation Along the Chinese-Nomad Frontier". Empires: Perspectives from Archaeology and History. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77020-0.

- Baumer, Christoph (2003). Southern Silk Road: In the Footsteps of Sir Aurel Stein and Sven Hedin (2nd ed.). Orchid Press. ISBN 978-974-8304-38-0.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691150345.

- Bielenstein, Hans (1986). "Wang Mang, the Restoration of the Han Dynasty, and Later Han". The Cambridge History of China, Volume 1: The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24327-0.

- Boulnois, Luce (2004). Silk Road: Monks, Warriors & Merchants on the Silk Road (Translated ed.). Hong Kong: Odyssey. ISBN 978-962-217-720-8.

- Bowman, John S. (2000). Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-11004-4.

- Chang, Chun-shu (1966). "Military Aspects of Han Wu-ti's Northern and Northwestern Campaigns". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 26. JSTOR 2718463.

- Chang, Chun-shu (2007a). The Rise of the Chinese Empire, Volume 1: Nation, State, and Imperialism in Early China, ca. 1600 B.C. – A.D. 8. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11533-4.

- Chang, Chun-shu (2007b). The Rise of the Chinese Empire, Volume 2: Frontier, Immigration, & Empire in Han China, 130 B.C. – A.D. 157. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-11534-0.

- Cheng, Dalin (2005). "The Great Wall of China". Borders and Border Politics in a Globalizing World. Lanham: SR Books. ISBN 0-8420-5103-1.

- Christian, David (1998). A History of Russia, Central Asia, and Mongolia. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 978-0-631-20814-3.

- Cosmo, Nicola Di (1999). "The Northern Frontier in Pre-Imperial China". The Cambridge History of Ancient China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-47030-7.

- Cosmo, Nicola Di (2002). Ancient China and its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-77064-5.

- Crespigny, Rafe de (2007). A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23 - 220 AD). Leiden: Brill Publishers. ISBN 90-04-15605-4.

- Crespigny, Rafe de (2009). "The Western Han Army". The Military Culture of Later Han. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03109-8.

- Deng, Yinke (2007). History of China (Translated ed.). Beijing: China Intercontinental Press. ISBN 978-7-5085-1098-9.

- Gernet, Jacques (1996). A History of Chinese Civilization (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-49781-7.

- Golden, Peter B. (2011). Central Asia in World History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515947-9.

- Graff, David A. (2002). Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300 – 900. London, New York City: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-23955-9.

- Grousset, René (2002). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia (8th print ed.). New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- Guo, Xuezhi (2002). The Ideal Chinese Political Leader: A Historical and Cultural Perspective. Westport: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-97259-2.

- Haar, Barend J. ter (2009). Het Hemels Mandaat: De Geschiedenis van het Chinese Keizerrijk (in Dutch). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-8964-120-5.

- Higham, Charles F.W. (2004). Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations. New York: Facts On File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4640-9.

- Hulsewé, Anthony François Paulus (1979). China in Central Asia: The Early Stage, 125 B.C.-A.D. 23. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-05884-2.

- Lewis, Mark Edward (2000). "The Han Abolition of Universal Military Service". Warfare in Chinese History. Leiden: Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-11774-7.

- Lewis, Mark Edward (2007). The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02477-9.

- Loewe, Michael (1986). "The Former Han Dynasty". The Cambridge History of China, Volume 1: The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24327-0.

- Loewe, Michael (2006). The Government of the Qin and Han Empires: 221 BCE - 220 CE. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-87220-818-6.

- Loewe, Michael (2009). "The Western Han Army". Military Culture in Imperial China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03109-8.

- Lovell, Julia (2006). The Great Wall: China Against the World, 1000 BC-AD 2000. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-4297-9.

- Millward, James A. (1998). Beyond the pass: Economy, Ethnicity, and Empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759-1864. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2933-8.

- Millward, James (2006). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- Morton, William Scott; Lewis, Charlton M. (2005). China: Its History and Culture (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-141279-4.

- Psarras, Sophia-Karin (2004). "Han and Xiongnu: A Reexamination of Cultural and Political Relations (II)". Monumenta Serica. 52. ISSN 0254-9948. JSTOR 40727309.

- Sima, Qian; Watson, Burton (translator) (1993). Records of the Grand Historian: Han Dynasty II (Revised ed.). Hong Kong: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231081672.

- Spakowski, Nicola (1999). Helden, Monumente, Traditionen: Nationale Identität und historisches Bewußtsein in der VR China (in German). Hamburg: Lit. ISBN 978-3-8258-4117-1.

- Tanner, Harold Miles (2009). China: A History. Indianapolis: Hackett. ISBN 978-0-87220-915-2.

- Torday, Laszlo (1997). Mounted Archers: The Beginning of Central Asian History. Edinburgh: Durham Academic Press. ISBN 1-900838-03-6.

- Tucker, Spencer C.; et al. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-667-1.

- Whiting, Marvin C. (2002). Imperial Chinese Military History: 8000BC-1912AD. Lincoln: iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-22134-9.

- Wintle, Justin (2002). The Rough Guide: History of China. London: Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-85828-764-5.

- Wu, Shu-hui (2013). "Debates and Decision-Making: The Battle of the Altai Mountains (Jinweishan 金微山) in AD 91". Debating War in Chinese History. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-22372-1.

- Yamashita, Michael; Lindesay, William (2007). The Great Wall: From Beginning to End. New York: Sterling Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4027-3160-0.

- Yü, Ying-shih (1967). Trade and Expansion in Han China: Study in the Structure of Sino-barbarian Economic Relations. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520013742.

- Yü, Ying-shih (1986). "Han Foreign Relations". The Cambridge History of China, Volume 1: The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. - A.D. 220. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24327-0.

- Yü, Ying-shih (1994). "The Hsiung-nu". The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24304-9.

- Yü, Ying-shih (2002). "Nomads and Han China". Expanding Empires: Cultural Interaction and Exchange in World Societies from Ancient to Early Modern Times. Wilmington: Scholarly Resources. ISBN 978-0-8420-2731-1.

- Zadneprovskiy, Y.A. (1999). "The Nomads of Northern Central Asia After the Invasion of Alexander". History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 2 (1st Indian ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishing. ISBN 81-208-1408-8.

Further reading

- Yap, Joseph P. (2019). The Western Regions, Xiongnu and Han, from the Shiji, Hanshu and Hou Hanshu. ISBN 978-1792829154.

_of_Kashgar%252C_73_CE.jpg.webp)

.png.webp)