Color in Chinese culture

Color in Chinese culture refers to the certain values that Chinese culture attaches to colors, like which colors are considered auspicious (吉利) or inauspicious (不利). The Chinese word for "color" is yánsè (顏色). In Classical Chinese, the character sè (色) more accurately meant "color in the face", or "emotion". It was generally used alone and often implied sexual desire or desirability. During the Tang Dynasty, the word yánsè came to mean all color. A Chinese idiom which is used to describe many colors, Wǔyánliùsè (五颜六色), can also mean colors in general.

Theory of the Five Elements

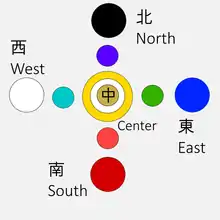

In traditional Chinese art and culture, black, red, qing (青) (a conflation of the idea of green and blue), white and yellow are viewed as standard colors. These colors correspond to the five elements of water, fire, wood, metal and earth, taught in traditional Chinese physics. Throughout the Shang, Tang, Zhou and Qin dynasties, China's emperors used the Theory of the Five Elements to select colors.

| Element | Wood | Fire | Earth | Metal | Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color | Green/blue | Red | Yellow | White | Black |

| Direction | east | south | center | west | north |

| Planet | Jupiter | Mars | Saturn | Venus | Mercury |

| Heavenly creature | Azure Dragon 青龍 | Vermilion Bird 朱雀 | Yellow Dragon 黃龍 | White Tiger 白虎 | Black Tortoise 玄武 |

| Heavenly Stems | 甲, 乙 | 丙, 丁 | 戊, 己 | 庚, 辛 | 壬, 癸 |

| Phase | New Yang | Full Yang | Yin/Yang balance | New Yin | Full Yin |

| Energy | Generative | Expansive | Stabilizing | Contracting | Conserving |

| Season | Spring | Summer | Change of seasons (Every third month) | Autumn | Winter |

| Climate | Windy | Hot | Damp | Dry | Cold |

| Development | Sprouting | Blooming | Ripening | Withering | Dormant |

| Livestock | dog | sheep/goat | cattle | chicken | pig |

| Fruit | Chinese plum | apricot | jujube | peach | Chinese chestnut |

| Grain | wheat | legume | rice | hemp | pearl millet |

Yellow

Yellow of a golden hue, corresponding with earth, is considered the most beautiful and prestigious color.[1] The Chinese saying Yellow generates Yin and Yang implies that yellow is the center of everything. Associated with but ranked above brown, yellow signifies neutrality and good luck. Yellow is sometimes paired with red in place of gold.

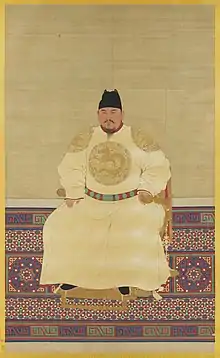

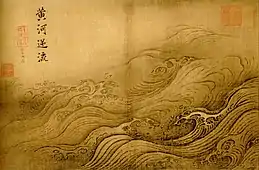

The Yellow River is the cradle of Chinese civilisation. Yellow was the emperor's color in Imperial China and is held as the symbolic color of the five legendary emperors of ancient China, such as the Yellow Emperor. The Yellow Dragon is the zoomorphic incarnation of the Yellow Emperor of the centre of the universe in Chinese religion and mythology. The Flag of the Qing dynasty featured golden yellow as the background. The Plain Yellow Banner and the Bordered Yellow Banner were two of the upper three banners of Later Jin and Qing dynasty.

Yellow often decorates royal palaces, altars and temples, and the color was used in the dragon robes and attire of the emperors.[1] It was a rare honour to receive the imperial yellow jacket.

Yellow also represents freedom from worldly cares and is thus esteemed in Buddhism. Monks' garments are yellow, as are elements of Buddhist temples. Yellow is also used as a mourning color for Chinese Buddhists.

Yellow is also symbolic of heroism, as opposed to the Western association of the color with cowardice.[2]

The Yellow River Breaches its Course by Ma Yuan (1160–1225), Song dynasty

The Yellow River Breaches its Course by Ma Yuan (1160–1225), Song dynasty.svg.png.webp) Flag of China 1889–1912 featuring yellow

Flag of China 1889–1912 featuring yellow_-_China-6184.jpg.webp) Yellow tiles and figures on the roof the Hall of Supreme Harmony in the Forbidden City

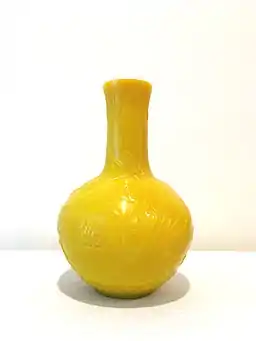

Yellow tiles and figures on the roof the Hall of Supreme Harmony in the Forbidden City A Peking glass vase in Imperial Yellow, a shade of yellow so named for the banner of the Qing Dynasty

A Peking glass vase in Imperial Yellow, a shade of yellow so named for the banner of the Qing Dynasty

Black

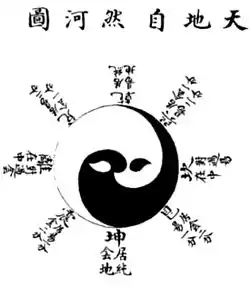

Black, corresponding to water, is a neutral color. The I Ching, or Book of Changes, regards black as Heaven's color. The saying "heaven and earth of black" was rooted in the observation that the northern sky was black for a long time. They believed Tian Di, or Heavenly Emperor, resided in the North Star. In astrology it is represented by the Black Tortoise.

The Taiji symbol uses black and white to represent the unity of yin and yang. Ancient Chinese people regarded black as the king of colors and honored black more consistently than any other color. Lao Zi said know the white, keep the black and the Dao school believes black is the color of the Dao.

In modern China, black is used in daily clothing. Black, along with white, is associated with death and mourning and was formerly worn at funerals, but depends on the age of passing.

White

White, corresponding with metal, represents gold and symbolises brightness, purity, and fulfilment. In astrology it is represented by the White Tiger.

White is also the color of mourning. It is associated with death and is used predominantly in funerals in Chinese culture.[2] Ancient Chinese people wore white clothes and hats only when they mourned for the dead.

Red / Vermilion

Red or vermilion, corresponding with fire, symbolizes good fortune and joy. In astrology it is represented by the Vermilion Bird.

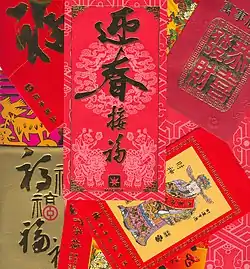

Red is found everywhere during Chinese New Year and other holiday celebrations and family gatherings. A red envelope is a monetary gift which is given in Chinese society during holiday or special occasions. The red color of the packet symbolizes good luck. Red is strictly forbidden at funerals as it is a traditionally symbolic color of happiness;[3] however, as the names of the dead were previously written in red, it may be considered offensive to use red ink for Chinese names in contexts other than official seals.

In modern China, red remains a very popular color and is affiliated with and used by the government.

Contemporary red envelopes

Contemporary red envelopes Red paper lanterns for sale in Shanghai. The color red symbolizes luck and is believed to ward away evil

Red paper lanterns for sale in Shanghai. The color red symbolizes luck and is believed to ward away evil Chinese seal and red seal paste

Chinese seal and red seal paste One of the red gates to the Forbidden City

One of the red gates to the Forbidden City

Blue / Azure / Green

Generally blue or azure and green is associated with health, prosperity, and harmony. In astrology it is represented by the Azure Dragon, which was also a national symbol in the past. The old term is qing. Azure was used for the roof tiles of the Temple of Heaven as well as its ornate interior and a number of other structures to represent heaven. It is also the color of jade as well as celadon that was developed to imitate it.

Separately, green hats are associated with infidelity and used as an idiom for a cuckold.[4] This has caused uneasiness for Chinese Catholic bishops, who in ecclesiastical heraldry would normally have a green hat above their arms. Chinese bishops have compromised by using a violet hat for their coat of arms. Sometimes this hat will have an indigo feather to further display their disdain for the color green.

Azure roof structure and name plaque of the Temple of Heaven

Azure roof structure and name plaque of the Temple of Heaven A Western Han dynasty green jade Bi disk, with dragon designs

A Western Han dynasty green jade Bi disk, with dragon designs

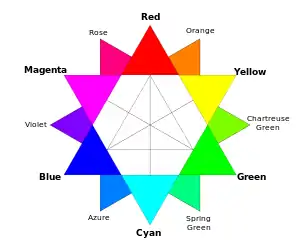

Intermediary colors

The five intermediary colors (五間色 wǔjiànsè) are formed as combinations of the five elemental colors. These are:[5]

- 绿 lǜ "green": The intermediary color of the east, combination of central yellow and eastern blue

- 碧 bì "emerald-blue": The intermediary color of the west, combination of eastern blue and western white

- 红 hóng "vermilion-red": The intermediary color of the south, combination of western white and southern red

- 紫 zǐ "violet": The intermediary color of the north, combination of southern red and northern black

- 硫 liú "horse-brown": The intermediary color of the center, combination of northern black and central yellow

See also

- Chinese art

- Culture of China

- Culture of the People's Republic of China

- Fashion of China

- Luck

- Numbers in Chinese culture

- Jing (Chinese opera)#Face design for information on color in Chinese opera face paintings

- Wuxing

References

- St. Clair, Kassia (2016). The Secret Lives of Colour. London: John Murray. pp. 84–85. ISBN 9781473630819. OCLC 936144129.

- "Psychology of Color: Does a specific color indicate a specific emotion? By Steve Hullfish | July 19, 2012". Archived from the original on 4 March 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- see Funeral § Asian funerals

- Norine Dresser, Multicultural Manners: New Rules of Etiquette for a Changing Society, ISBN 0-471-11819-2, 1996, page 67

- Kim, Yung-sik (2014). Questioning Science in East Asian Contexts: Essays on Science, Confucianism, and the Comparative History of Science. London: Brill. p. 32. ISBN 9789004265318.