2011 Atlantic hurricane season

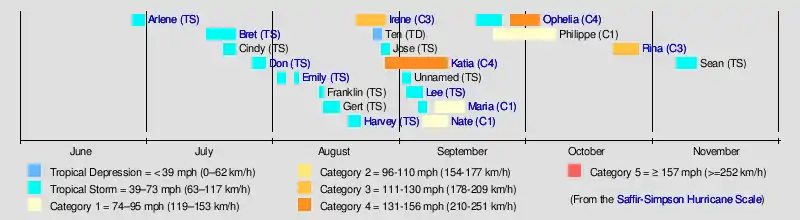

The 2011 Atlantic hurricane season was the second in a group of three very active Atlantic hurricane seasons. The above-average activity was mostly due to a La Niña that persisted during the previous year. The season is tied with 1887, 1995, 2010, and 2012 for the fourth highest number of tropical storms since record-keeping began in 1851. Although the season featured 19 tropical storms, most were weak. Only seven of them intensified into hurricanes, and only four of those became major hurricanes: Irene, Katia, Ophelia, and Rina. The season officially began on June 1 and ended on November 30, dates which conventionally delimit the period during each year in which most tropical cyclones develop in the Atlantic Ocean. However, the first tropical storm of the season, Arlene, did not develop until nearly a month later. The final system, Tropical Storm Sean, dissipated over the open Atlantic on November 11.

| 2011 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | June 28, 2011 |

| Last system dissipated | November 11, 2011 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Ophelia |

| • Maximum winds | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 940 mbar (hPa; 27.76 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 20 |

| Total storms | 19 |

| Hurricanes | 7 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 4 |

| Total fatalities | 118 total |

| Total damage | $17.39 billion (2011 USD) |

| Related articles | |

Due to the presence of a La Niña in the Pacific Ocean, many pre-season forecasts called for an above-average hurricane season. In Colorado State University (CSU)'s spring outlook, the organization called for 16 named storms and 9 hurricanes, of which 4 would intensify further into major hurricanes. On May 19, 2011, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) issued their pre-season forecast, predicting 12–18 named storms, 6–10 hurricanes, and 3–6 major hurricanes. Following a quick start to the season, NOAA subsequently increased their outlook to 14–19 named storms, 7–10 hurricanes, and 3–5 major hurricanes on August 4; CSU made no changes to the number of cyclones forecast throughout the year.

Many tropical cyclones affected land during the 2011 season; most impacts, however, did not result in a significant loss of life or property. On June 29, Arlene made landfall in Mexico near Cabo Rojo, Veracruz, causing over $223 million (2011 USD) damage and killing 22 people.[nb 1] Tropical Storm Harvey moved into the coastline of Central America in mid-August, and three deaths were reported as a result. During the month of September, Tropical Storm Lee and Hurricane Nate moved into the central United States Gulf Coast and central Mexico, respectively; the former led to 18 deaths, and the latter caused 5 fatalities. As an extratropical cyclone, Lee caused significant damage in the form of flooding across the Northeast United States, especially in New York and Pennsylvania. The deadliest and most destructive cyclone of the season developed east of the Lesser Antilles on August 21. Hurricane Irene caused significant impact across some of the Caribbean Islands and United States Eastern Seaboard, leaving about $14.2 billion in damage and resulting in the name's retirement. Overall, the season resulted in 112 deaths and nearly $17.4 billion in damage.

Seasonal forecasts

| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

Ref |

| Average (1981–2010) | 12.1 | 6.4 | 2.7 | [1] | |

| Record high activity | 30 | 15 | 7 | [2] | |

| Record low activity | 4 | 2 | 0† | [2] | |

| ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– | |||||

| TSR | December 6, 2010 | 16 | 8 | 4 | [3] |

| CSU | December 8, 2010 | 17 | 9 | 5 | [4] |

| TSR | April 4, 2011 | 14 | 8 | 4 | [5] |

| CSU | April 6, 2011 | 16 | 9 | 5 | [6] |

| NOAA | May 19, 2011 | 12–18 | 6–10 | 3–6 | [7] |

| TSR | May 24, 2011 | 14 | 8 | 4 | [8] |

| UKMO | May 26, 2011 | 13 | N/A | N/A | [9] |

| CSU | June 1, 2011 | 16 | 9 | 5 | [10] |

| FSU COAPS | June 1, 2011 | 17 | 9 | N/A | [11] |

| TSR | June 6, 2011 | 14 | 8 | 4 | [12] |

| TSR | July 4, 2011 | 14 | 8 | 4 | [13] |

| WSI | July 26, 2011 | 15 | 8 | 4 | [14] |

| CSU | August 3, 2011 | 16 | 9 | 5 | [15] |

| TSR | August 4, 2011 | 16 | 9 | 4 | [16] |

| NOAA | August 4, 2011 | 14–19 | 7–10 | 3–5 | [17] |

| WSI | September 21, 2011 | 21 | 7 | 4 | [18] |

| ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– | |||||

| Actual activity |

19 | 7 | 4 | ||

| † Most recent of several such occurrences. (See all) | |||||

In advance of, and during, each hurricane season, several forecasts of hurricane activity are issued by national meteorological services, scientific agencies, and noted hurricane experts. These include forecasters from the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)'s National Hurricane and Climate Prediction Center's, Philip J. Klotzbach, William M. Gray and their associates at Colorado State University (CSU), Tropical Storm Risk, and the United Kingdom's Met Office. The forecasts include weekly and monthly changes in significant factors that help determine the number of tropical storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes within a particular year. As stated by NOAA and CSU, an average Atlantic hurricane season between 1981-2010 contains roughly 12 tropical storms, 6 hurricanes, 3 major hurricanes, and an Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) Index of 66-103 units.[1][19] NOAA typically categorizes a season as either above-average, average, of below-average based on the cumulative ACE Index; however, the number of tropical storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes within a hurricane season is considered occasionally as well.[1]

Pre-season forecasts

On December 6, 2010, Tropical Storm Risk (TSR), a public consortium that comprises experts on insurance, risk management and seasonal climate forecasting at University College London, issued an extended-range forecast for the 2011 Atlantic hurricane season, calling for tropical cyclone activity roughly 40% above the 1950–2010 average. The team called for 15.6 (±4.3) tropical storms, 8.4 (±3.0) hurricanes, and 4.0 (±1.7) major hurricanes, with a cumulative ACE Index of 141 (±58).[3] Two days later, Colorado State University issued its first extended-range forecast for the 2011 season. In its report, the organization predicted an above-average hurricane season with 17 named storms, 9 hurricanes, and 5 major hurricanes. In addition, the team expected an ACE value of approximately 165, citing that El Niño conditions had little chance to develop by the start of the season. The team also predicted that there was a higher chance of a tropical cyclone hitting the United States coastline when compared to 2010.[4] TSR released an updated forecast on April 4, lowering the number of predicted cyclones by one.[5] On April 4, 2011, CSU revised their December forecast slightly, predicting 16 named storms, 9 hurricanes, and 5 major hurricanes.[6]

On May 19, 2011, NOAA released their first forecast for the 2011 Atlantic hurricane season. The organization expected 12–18 named storms, 6–10 hurricanes, and 3–6 major hurricanes would form in the Atlantic during 2011, citing above-normal sea surface temperatures, a weakening La Niña, and the effect of the warm regime of the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation. NOAA also stated that, when looking at climate models, "activity comparable to some of the active seasons since 1995" could occur.[7] On May 26, the UK Met Office (UKMO) issued a forecast of a slightly above-average season. They predicted 13 tropical storms with a 70% chance that the number would fall between 10 and 17. However, they did not – and do not – issue forecasts on the number of hurricanes and major hurricanes. The team also predicted an ACE Index of 151 with a 70% chance that the index would be in the range 89 to 212.[9]

Mid-season forecasts

On June 1, CSU released their mid-season predictions, with numbers unchanged from those published in April.[10] Concurrently, the Florida State University Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies (FSU COAPS) issued its third annual Atlantic hurricane season forecast, predicting 17 named storms, 9 hurricanes, and an ACE Index of 163. No prediction for the number of major hurricanes was made.[11] A little over a month later, Weather Services International (WSI) issued their first forecast for the season. A total of 15 named storms, 8 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes were expected to develop for the entirety of the season.[14] On August 3, CSU issued a mid-season update, though no change in predictions from their April outlook was made.[15] The following day, NOAA issued their mid-season and final forecast for the season, calling for 14-19 named storms, 7-10 hurricanes, and 3-5 major hurricanes. The increase in numbers when compared to the pre-season forecast was due to the near-record start to the season.[17] TSR also issued their sixth and final outlook on August 4, which increased the number of tropical storms to 16 and the number of hurricanes to 9, but continued to predict that there would be 4 major hurricanes.[16] The final forecast for the 2011 season was issued by WSI on September 21, in which the organization called for 21 named storms, 7 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes; the philosophy for the increase in numbers was unchanged from CSU's.[18]

Seasonal summary

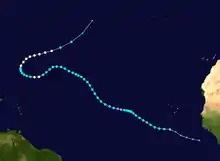

The Atlantic hurricane season officially began on June 1, 2011.[20] It was an above average season in which twenty tropical cyclones formed. Nineteen of the twenty depressions attained tropical storm status, tied with 1887, 1995, 2010, and later the 2012 season for the third highest number of named storms since record-keeping began in 1851. Seven of these tropical storms became hurricanes, while four of those hurricanes further intensified into major hurricanes.[21] The season was more active than usual due to lower than average wind shear, warmer than average sea surface temperatures, and the presence of a La Niña.[22] Collectively, the tropical cyclones of this season resulted in nearly $18.5 billion in damage and there were 114 deaths; a majority of it was caused by Hurricane Irene and Tropical Storm Lee.[23] The season officially ended on November 30, 2011.[20]

| Rank | Cost | Season |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ≥ $294.703 billion | 2017 |

| 2 | $172.297 billion | 2005 |

| 3 | $72.341 billion | 2012 |

| 4 | $61.148 billion | 2004 |

| 5 | ≥ $51.146 billion | 2020 |

| 6 | ≥ $50.126 billion | 2018 |

| 7 | ≥ $48.855 billion | 2008 |

| 8 | $27.302 billion | 1992 |

| 9 | ≥ $17.485 billion | 2016 |

| 10 | $17.39 billion | 2011 |

Tropical cyclogenesis began in the month of June, with Tropical Storm Arlene forming on June 28. After Arlene dissipated on July 1, there was about a two-week lull in activity, before Bret, Cindy, and Don developed in the latter half of July. August was the most active month of the season, featuring eight tropical cyclones – Emily, Franklin, Gert, Harvey, Irene, Tropical Depression Ten, Jose, and Katia. The number of named storms in August was well above the 1944-2010 average of four,[24] and just one short of the record of eight set in 2004 and later in 2012,[25] but the number of hurricanes was below the mean.[24] September was slightly above average,[26] with 5 named storms, 2 hurricanes, and 1 major hurricane and featuring the unnamed tropical storm, Lee, Maria, Nate, Ophelia, and Philippe. Ophelia was the most intense tropical cyclone of the season, peaking as a Category 4 hurricane with winds of 140 mph (220 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 940 mbar (28 inHg). The next two months featured one system each, with Rina developing in October and Sean forming in November. Sean was the final storm of the season and became extratropical on November 11.[27]

The season's activity was reflected with an above-average cumulative ACE rating of 125.[21] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, like Philippe, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, like Ophelia have high ACEs. It is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 39 mph (63 km/h), the threshold for tropical storm strength. Subtropical cyclones, including the early portions of Sean, are excluded from the total.[28]

Systems

Tropical Storm Arlene

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 28 – July 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 993 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged into the eastern Atlantic on June 13. Tracking westward, the disturbance remained disorganized prior to reaching the western Caribbean. Cyclonic rotation became increasingly evident on satellite imagery, though organization was halted by the disturbance's passage over the Yucatán Peninsula on June 26. After emerging into the Bay of Campeche, favorable environmental conditions allowed for the development of Tropical Storm Arlene by 18:00 UTC on June 28. Moving generally westward due to the influence of high pressure to the cyclone's north, Arlene gradually intensified, reaching its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 993 mbar (29.32 inHg) at 12:00 UTC on June 30; the strong tropical storm moved ashore in Mexico near Cabo Rojo, Veracruz, about an hour later. Once inland, the center of circulation became increasingly diffuse, and the storm dissipated over the Sierra Madre Mountains early on July 1.[29]

Numerous tropical cyclone watches and warnings were issued for the coastline of Mexico shortly after the formation of Arlene; once inland, all were discontinued.[29] Despite its relatively weak strength, Arlene produced isolated rainfall totals in excess of 9 in (230 mm).[30] High amounts of precipitation led to numerous mudslides and flooding, causing an estimated $223.4 million in damage.[31][32][33] A total of 22 deaths were reported in association with Tropical Storm Arlene.[29] Although the center of circulation remained over Mexico, the storm's far-reaching effects brought minimal relief to drought-stricken portions of southern Texas and Florida.[34]

Tropical Storm Bret

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 17 – July 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 995 mbar (hPa) |

An area of low pressure formed on the southern extent of a stalled cold front just off the East Coast of the United States on July 16. Tracking south-southeast, the low-pressure center was initially baroclinic in nature, but quickly transitioned into a warm-core low over the warm waters of the western Atlantic. Decreasing vertical wind shear allowed for the development of convection – shower and thunderstorm activity – atop the low-level circulation, and Dvorak satellite classifications were initiated early on July 17 given the organization on satellite imagery. Following an aircraft reconnaissance flight into the disturbance that afternoon, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) subsequently classified the system as Tropical Depression Two at 18:00 UTC on July 17 about 100 mi (160 km) northwest of Great Abaco Island in the Bahamas. After about six hours, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Bret.[35]

As the system turned northeastward, the formation of an anticyclone atop Bret's center provided favorable conditions for intensification; accordingly, an eye-like feature and an eyewall – a ring of thunderstorms around the eye where typically the most intense convection associated with a tropical cyclone is located – were noted on microwave satellite imagery during the afternoon hours of July 18. At 18:00 UTC, the system attained its peak intensity with winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 995 mbar (29.38 inHg). After moving over increasingly cool sea surface temperatures, the cyclone began to gradually weaken. Bret weakened to a tropical depression at around 00:00 UTC on July 22 and no longer met the criteria of a tropical cyclone by 12:00 UTC, while positioned approximately 375 mi (605 km) north of Bermuda.[35] Bret left minimal impact in the Bahamas, with rainfall alleviating drought conditions.[36] Precipitation was also generally beneficial on Bermuda, though minor flooding affected some local businesses in poor-drainage areas.[37]

Tropical Storm Cindy

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

_Jul_21_2011.jpg.webp)  | |

| Duration | July 20 – July 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min) 994 mbar (hPa) |

On July 17, an area of showers and thunderstorms, associated with the same frontal system that spawned Tropical Storm Bret, consolidated around a developing area of low pressure about 345 mi (555 km) west-southwest of Bermuda. Tracking east-northeastward, the system gradually organized and became better defined. The disturbance produced moderate rains while passing south of the territory, peaking at 1.16 in (29 mm); gusty winds were also observed. At 06:00 UTC on July 20, the low developed into a tropical depression east of Bermuda. Embedded within the mid-latitude westerlies, the depression moved northeast and maintained this general direction for the remainder of its existence.[38]

Six hours after formation, the system strengthened into Tropical Storm Cindy. Convection steadily increased over the storm, and a ragged eye-like feature appeared on both visible and microwave satellite imagery. Corresponding with this, Cindy attained its peak intensity late on July 21, with winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) and a barometric pressure of 994 mbar (29.35 inHg). Shortly thereafter, the storm moved over waters cooler than 78.8 °F (26 °C). Throughout July 22, convection diminished and the system transitioned into an extratropical cyclone about 985 mi (1,585 km) southwest of Ireland. The remnants persisted for another 12 hours before degenerating into a trough over the North Atlantic on July 23.[38]

Tropical Storm Don

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 27 – July 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 997 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged off the western coast of Africa on July 16. Tracking westward, the disturbance produced sporadic convection, but remained disorganized through its passage into the Caribbean on July 23. Once there, showers and thunderstorms began to develop within an environment marginally conducive for tropical cyclogenesis. A broad area of low pressure formed and consolidated over the northwestern Caribbean Sea, and the NHC subsequently designated Tropical Depression Four on July 27; the system further intensified into Tropical Storm Don at 18:00 UTC. Steered west-northwestward by a subtropical ridge across over the southeastern United States, the cyclone strengthened initially under low wind shear, attaining a peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 997 mbar (29.44 inHg). Despite low shear, Don was met with a significantly more stable environment as it emerged into the Gulf of Mexico.[39]

Convection around the center of the storm gradually diminished as a result of a lack of vertical instability, and a decrease in sustained winds was observed accordingly. Don weakened to a tropical depression as it moved ashore in Texas, along the Padre Island National Seashore, and continued west-northwestward thereafter; the system degenerated into a remnant area of low pressure by 06:00 UTC on July 30. As a tropical cyclone, Don prompted tropical cyclone advisories for the southern Texas coastline. Due to its abrupt weakening prior to landfall, rainfall totals and wind observations along the warned areas were scarce; a maximum precipitation total of 2.56 in (65 mm) was documented near Bay City, Texas, and a peak wind gust of 41 mph (66 km/h) was recorded at Waldron Field. The storm produced storm surge values lower than 2 ft (0.61 m) as well. No damage was reported.[39]

Tropical Storm Emily

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 2 – August 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min) 1003 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged off the west coast of Africa on July 25. Tracking westward, the disturbance gradually consolidated as multiple centers of circulation eventually dissipated and a new one formed. A marginally favorable atmospheric environment allowed for convection to develop, and a reconnaissance aircraft flight into the system led to the classification of Tropical Storm Emily around 00:00 UTC on August 2 near Dominica. Turning west-northwestward along the southwest edge of a large subtropical ridge to its northeast, Emily remained relatively disorganized on satellite imagery due to strong westerly wind shear. Despite a large burst of convection south of Hispaniola on August 3, the center of circulation accelerated west-northwestward, with a mid-level center moving inland over the island. At 18:00 UTC the following day, Emily degenerated into a tropical wave.[40]

The mid-level remnants of Emily continued northwestward, with a new area of low pressure developing over the Bahamas. The low regenerated into a tropical depression at 18:00 UTC on August 6; six hours later, it re-intensified into Tropical Storm Emily. However, strong wind shear exposed the center of circulation once again. At 12:00 UTC on August 7, Emily degenerated into a remnant area of low pressure northeast of the Bahamas.[40] Heavy rainfall and landslides in Martinique damaged 29 homes.[41] One indirect death was reported on the island. In Puerto Rico, flooding and mudslides damaged roads, homes, and crops.[40] Additionally, around 18,500 people lost electricity after winds damaged an electrical grid.[42] About $5 million in infrastructural damage occurred.[43] In Dominican Republic, flooding and mudslides left 56 communities isolated and caused three people to drown.[44][45] Flooding in Haiti damaged over 300 homes and destroyed several cholera treatment centers.[40][46] One death occurred in the country.[47] The storm brought up to 7.9 in (200 mm) of rainfall to the Bahamas.[48]

Tropical Storm Franklin

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 12 – August 13 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1004 mbar (hPa) |

A low pressure area developed in association with a slow-moving frontal boundary over western Atlantic on August 10 and August 11. Tracking northeastward in response to deep southeasterly flow, the disturbance was initially slow to organize, but a marked organization of thunderstorm activity took place on August 12. Thus, Tropical Depression Six developed at 18:00 UTC while situated roughly 260 mi (420 km) north of Bermuda.[49] The system brought unsettled weather to island, with rainfall reaching 0.07 in (1.8 mm) at L.F. Wade International Airport.[50] Moving northeastward, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Franklin at 06:00 UTC on August 13, following a large burst of convection over its center. Six hours later, Franklin peaked with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h), before encountering increasing wind shear and decreasing ocean temperatures. Rapid deterioration of the storm's structure took place as environmental conditions became increasingly hostile, with convection being sheared well away from the center. Franklin began acquiring extratropical characteristics and completed its transition into an extratropical cyclone late on August 13. The remnants degenerated into a trough of low pressure early on August 16.[49]

Tropical Storm Gert

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 13 – August 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 1000 mbar (hPa) |

During the second week of August, a weak low-pressure area, located east of Bermuda, became associated with a synoptic-scale trough. Moving west-southwestward, it interacted with an upper low and eventually developed into a small low pressure by August 13. After the low become very well-defined with a tight circulation and deep convection, it was designated as a tropical depression at 18:00 UTC that day, about 360 mi (580 km) southeast of Bermuda. As the depression curved west-northwestward along the weakening subtropical ridge, it intensified into Tropical Storm Gert early on August 14. As Gert neared Bermuda, a small eye-like feature became apparent on radar imagery. Coinciding with this, Gert reached its peak intensity with winds of 60 mph (100 km/h).[51] Passing roughly 90 mi (150 km) east of Bermuda, Gert brought light rain and winds up to 25 mph (40 km/h).[50] By August 16, convection had mostly dissipated due to increasing wind shear and cooler water temperatures, degenerating into post-tropical cyclone about 500 mi (800 km) northeast of Bermuda. The remnant low dissipated well east of Newfoundland on August 17.[51]

Tropical Storm Harvey

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 19 – August 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 994 mbar (hPa) |

On August 10, a tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic from the west coast of Africa. After moving westward across the Atlantic and Caribbean for several days, the wave developed into a tropical depression about 100 mi (160 km) east-northeast of Cabo Gracias a Dios at the Honduras–Nicaragua border. Tracking over the warm waters of the northwestern Caribbean, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Harvey while just offshore Honduras. Additional intensification occurred, with Harvey attaining its peak intensity with winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) prior to landfall in Belize on August 20. Harvey weakened to a tropical depression on August 21, but re-intensified to a tropical storm after emerging into the Bay of Campeche. Early on August 22, it made landfall near Punta Roca Partida, Veracruz, then weakened and dissipated several hours later.[52]

The precursor disturbance produced squally weather and gusty winds throughout the Lesser Antilles. On Saint Croix in the United States Virgin Islands, gusty winds downed trees, which struck power lines, leaving minor electrical outages.[53] Along its path, Harvey dropped heavy rainfall across much of Central America.[52] Strong winds and heavy precipitation were reported in Belize, damaging or destroying homes in Crooked Tree.[54] A tornado in northern Belize also caused wind damage in a few villages.[55] Heavy rains in Mexico triggered numerous landslides, one of which killed three people. Two other fatalities occurred in the country. Landslides and overflowing rivers damaged 36 homes and 334 homes in the states of Chiapas and Veracruz, respectively.[52]

Hurricane Irene

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 21 – August 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min) 942 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave developed into Tropical Storm Irene about 190 mi (305 km) east of the Lesser Antilles early on August 21. The storm made landfall in Saint Croix as a strong tropical storm later that day. Early on August 21, the storm struck Puerto Rico. While crossing the island, Irene strengthened into a Category 1 hurricane. The storm moved parallel to the coast of Hispaniola, continuing to slowly intensify in the process. Shortly before making four landfalls in the Bahamas, Irene peaked as a 120 mph (195 km/h) Category 3 hurricane. Thereafter, the storm slowly weakened as it struck the Bahamas and then curved northward after passing east of Grand Bahama. Irene was downgraded to a Category 1 hurricane before making landfall near Cape Lookout, North Carolina, on August 27. Early on the following day, the storm re-emerged into the Atlantic from southeastern Virginia. Although the cyclone remained a hurricane over water, it weakened to a strong tropical storm while making landfall at Little Egg Inlet in New Jersey on August 28. A few hours later, Irene struck Brooklyn, New York City, while slightly weaker. Early on August 29, Irene became extratropical near the New Hampshire–Vermont state line, before being absorbed by a frontal system over Labrador on August 30.[56]

In Puerto Rico, heavy rainfall caused several rivers burst their banks, damaging roads and crops, particularly in Maunabo and Yabucoa.[57] One death occurred after a woman attempted to drive across a bridge over a rain-swollen river, but her car was swept away. Strong winds toppled many trees and utility poles, leaving over 1 million people without electricity.[58] Overall, damage in Puerto Rico totaled approximately $500 million. In Dominican Republic, flooding displaced more than 37,700 people and left at least 88 communities isolated.[59][60] A total of 2,292 homes were damaged, 16 of which were rendered beyond repair.[60] Throughout the country, there were five deaths and about $30 million in damage.[56][61] In Haiti, brisk winds in the Port-au-Prince area blew down many refuge tents home to victims from the major 2010 earthquake.[62] Two people were killed after being caught in rain-swollen rivers.[63] In the Bahamas, strong winds damaged at least 40 homes on Mayaguana, while dozens of homes on Acklins were destroyed.[64] On Cat Island, the storm caused "millions of dollars" in structural damage and left many people homeless.[65] Damage throughout the Bahamas reached about $40 million.[66]

Irene impacted the East Coast of the United States from Florida to Maine.[56] Rough seas along the coast of Florida resulted in minor beach erosion and the deaths of two people. Overall, damage in Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina was minimal. Eastern North Carolina was lashed with heavy rainfall, strong winds, and abnormally high tides. In all, over 1,100 homes were destroyed and thousands of others were damaged in North Carolina.[67] Damage in the state reached about $1.2 billion.[68] New Jersey was also hit hard by flooding, strong winds, and storm surge. A number of rivers and creeks reached record or near record levels. Winds left approximately 1.6 million people without electricity. About 200,000 buildings and homes across the state suffered some degree of damage.[69] The cost of damage throughout the state was approximately $1 billion.[68] In New York, winds left almost 350,000 homes and businesses without power in Nassau and Suffolk counties alone,[70] but the state received only minor wind damage overall. Storm surge left hundreds of millions in damage in New York City and on Long Island. Severe flooding occurred in the Catskill Mountains region, with three towns rendered completely uninhabitable.[56] Damage in the state of New York was estimated at over $1.3 billion.[68] In Vermont, rainfall totals of 4–7 in (100–180 mm) were common. Approximately 800 homes were damaged or destroyed. Additionally, nearly 2,400 roads and 300 bridges were damaged or washed away, several of which were covered bridges built more than 100 years prior to the storm. Flooding in Vermont was considered the worst since the flood of November 1927,[56] with uninsured losses alone reaching about $733 million. The other states of New England experienced extensive flooding, but to a less degree. The storm left at least 58 deaths and about $15.8 billion in damage in the United States,[68] which makes it the seventh costliest hurricane in the country.[71] The remnants of Irene also brought flooding to Canada, especially Quebec. One death and about $130 million in insured damage were reported.[72][73]

Tropical Depression Ten

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 25 – August 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) 1006 mbar (hPa) |

A well-organized tropical wave moved into the eastern Atlantic on August 22. Tracking westward at a fast pace, the wave gradually developed shower and thunderstorm activity and a closed center of low pressure. Curved bands extended from the center by 00:00 UTC on August 25, indicating the development of a tropical depression; at this time, the system was centered about 405 mi (650 km) west-southwest of the southernmost Cape Verde Islands. Unfavorable northeasterly shear prevented intensification, with the depression peaking with winds of 35 mph (55 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 1006 mbar (hPa; 29.71 inHg) at the time of formation. As a mid-level ridge to the north of the cyclone weakened, it turned west-northwest while gradually weakening. By late on August 26, little convection existed over the center of circulation. At 00:00 UTC on August 27, the depression degenerated into a remnant area of low pressure and dissipated a few hours later after the center deteriorated into a trough.[74]

Tropical Storm Jose

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 27 – August 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1006 mbar (hPa) |

A mesoscale convective system developed north of an upper-level low east-southeast of Bermuda on August 25. A small mid-level area of low pressure formed on the western side of the convective complex later that same day, gradually developing into the lower levels of the atmosphere. As convection near the center of circulation increased in coverage and intensity, the system developed into a tropical depression at 06:00 UTC on August 27. Six hours later, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Jose. After formation, strong wind shear from nearby Hurricane Irene slowed, and eventually halted, development trends. Jose attained its peak intensity with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1006 mbar (hPa; 29.71 inHg) but slowly weakened thereafter. Accelerating to the north and northeast, shower and thunderstorm activity gradually diminished, the low-level circulation became exposed, and the NHC determined Jose degenerated into a remnant area of low pressure near 00:00 UTC on August 29, roughly 135 mi (220 km) north-northwest of Bermuda. As a tropical cyclone, Jose produced tropical storm-force wind gusts on the island and several nearby buoys.[75]

Hurricane Katia

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 29 – September 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min) 942 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave developed into a tropical depression about 430 mi (690 km) southwest of the southernmost Cape Verde Islands early on August 29. It intensified into a tropical storm the following day and further developed into a hurricane by September 1, although unfavorable atmospheric conditions hindered strengthening thereafter. As the storm began to recurve over the western Atlantic, favorable conditions allowed Katia to become a major hurricane by September 5 and peak as a Category 4 hurricane with winds of 140 mph (220 km/h). However, internal core processes, increased wind shear, an impinging cold front, and increasingly cool ocean temperatures caused the cyclone to weaken almost immediately. Katia ultimately transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on September 10 about 290 mi (465 km) south-southeast of Newfoundland. At 00:00 UTC on September 13, Katia's remnant merged with a larger extratropical system, over the North Sea.[76]

Although Katia passed well north of the Lesser Antilles, a yellow alert was hoisted for Guadeloupe to notify residents of dangerous seas.[77] Strong rip currents along the East Coast of the United States led to the deaths of two swimmers.[78][79] After losing its tropical characteristics, Katia prompted the issuance of numerous warnings across Europe. Hurricane-force winds impacted numerous locations,[80] downing trees and power poles, leaving thousands of people without electricity.[81] The storm was responsible for two deaths in the United Kingdom, with one from when a tree fell on a vehicle in County Durham and another during a multi-car accident on the M54 motorway resulting from adverse weather conditions. The post-tropical cyclone caused approximately £100m ($157 million) in damage in the United Kingdom alone.[76]

Unnamed tropical storm

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 1 – September 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min) 1002 mbar (hPa) |

As part of their routine post-season analysis, the NHC identified an additional tropical storm. In late August, an area of convection that formed to the southwest of Bermuda organized into a distinct low pressure area. At around 00:00 UTC on September 1, a tropical depression formed about 335 mi (535 km) north of Bermuda. It initially drifted erratically northeastward due to its position within a stationary front. Despite moderate southwesterly wind shear, the depression intensified into a tropical storm after about 12 hours, based on an increase of convection over the center. At that time, the storm attained maximum sustained winds of 45 mph (75 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1,002 mbar (29.6 inHg).[82]

The thunderstorms continued to pulsate, resulting in the winds fluctuating slightly. Additionally, the intermittent nature of the convection, as well as uncertainty on whether it was associated with a cold front, prevented the storm from being classified as a tropical cyclone in real time. On September 2, a Tropical Weather Outlook (TWO) by the NHC stated that "only a slight increase in organization [would] result in the formation of a tropical storm."[83] That day, an approaching trough caused the storm to accelerate northeastward. Cooler waters and increased wind shear stripped away the convection, resulting in the storm becoming extratropical early on September 3. The remnants continued northeastward, with the circulation dissipating by September 4.[82]

Tropical Storm Lee

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 2 – September 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min) 986 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave developed into the season's thirteen tropical depression in the Gulf of Mexico about 255 mi (360 km) southwest of the mouth of the Mississippi River at 00:00 UTC on September 2. About 12 hours later, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Lee. The cyclone moved slowly north-northwestward and continued to strengthen. However, Lee transitioned into a subtropical storm at 12:00 UTC on September 3 due to a significantly expanded wind field, further interaction with an upper-level low pressure, and weak convection near the center. Around that time, the cyclone peaked with maximum sustained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 986 mbar (29.1 inHg). Lee weakened slightly before making landfall near Intracoastal City, Louisiana, at 10:30 UTC on September 4. After moving inland, the storm moved northeastward and merged with a cold front over eastern Louisiana early on September 5. The remnant low dissipated over Georgia by late on the following day.[84]

In Louisiana, storm surge from Lake Pontchartrain flooded more than 150 homes in Jefferson and St. Tammany parishes. Freshwater flooding also occurred in low-lying areas of southeastern Louisiana and southern and central Mississippi due to 10–15 in (250–380 mm) of rainfall across the area. Several roads were inundated, while 35 roads were damaged, 5 of which were washed out, in Neshoba County, Mississippi. The storm spawned 46 tornadoes, one of which damaged about 400 homes in Cherokee County, Georgia. In the Mid-Atlantic, the remnants of Lee produced over 10 in (250 mm) of rainfall in a wide area, causing worse flooding than in June and July 2006 and Hurricane Agnes in 1972. About 100,000 people in Pennsylvania evacuated, including the governor's residence. In Dauphin and Lebanon counties alone, nearly 5,000 dwellings were damaged or demolished. Extensive flooding also occurred in western New York, particularly in Binghamton, Endicott, Johnson City, Owego, Vestal, and Waverly.[84] Overall, Lee resulted in 21 deaths and about $1.6 billion in damage.[84][85][86][87]

Hurricane Maria

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 6 – September 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min) 983 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave developed into a tropical depression about 700 mi (1,100 km) west-southwest of the southern Cape Verde Islands on late September 6. Early the following day, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Maria. The system reached winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) on September 8, before encountering stronger wind shear and cooler water temperatures near the Leeward Islands, degenerating into a low-pressure area on September 9. It slowly curved toward the north and northeast around the western periphery of the subtropical ridge, and regained tropical storm status on September 10. Maria further strengthened to attain hurricane status while making its closest approach to Bermuda. The cyclone peaked with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) on September 16, but soon weakened due to an increase in wind shear and cooler ocean temperatures. Maria made landfall near Cape St. Mary's, Newfoundland, on September 16, before being absorbed by a frontal system later that day.[88]

Despite its poor organization, Maria brought heavy rainfall to portions of the eastern Caribbean, especially Puerto Rico. Numerous roadways and homes were flooded, with 150 dwellings in the Yabucoa area receiving water damage. Many people were forced to evacuate after water and mud began entering their homes. Nearly 16,000 people were without electricity in Puerto Rico.[88] Maria left approximately $1.36 million in damage on the island.[89] In addition, tropical storm-force winds were observed on many of the U. S. Virgin Islands. As the system passed west of Bermuda, brief tropical storm-force sustained winds were recorded, along with higher gusts; rainfall on the island, however, was minimal. In Newfoundland, fairly strong winds were recorded, but rainfall totals were generally minimal.[88]

Hurricane Nate

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 7 – September 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min) 994 mbar (hPa) |

On September 5 and September 6, a frontal trough stalled in the Bay of Campeche. A low developed and organized sufficiently to be designated as Tropical Storm Nate at 18:00 UTC on September 7. Moving in an erratic motion at a very slow pace, Nate continued to strengthen. Late on September 8, the cyclone intensified into a Category 1 hurricane, peaking with maximum sustained winds of 75 mph (120 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 994 mbar (29.4 inHg). Due to the storm's slow movement, Nate began to upwell cooler waters in its wake, while very dry air began entering into the storm, resulting in weakening. Around 16:00 UTC on September 11, Nate made landfall in Mexico near Tecolutla, Veracruz, with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h). Shortly after making landfall, much of Nate's showers and thunderstorms diminished, with the system generating into a remnant low by 00:00 UTC on September 12, which dissipated about six hours later.[90]

In the Bay of Campeche, 10 oil rig workers evacuated the Trinity II rig, but were forced to abandon their lifeboat. Seven of the ten were rescued, though the other four perished.[90] The storm brought up to 9.84 in (250 mm) of precipitation to southern Veracruz, causing flooding that damaged 839 homes.[91] One person died in the state after being struck by lightning.[90]

Hurricane Ophelia

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

.jpg.webp)  | |

| Duration | September 20 – October 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min) 940 mbar (hPa) |

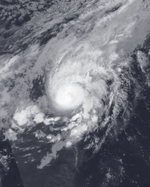

On September 19, a tropical wave developed into a tropical depression about 1,300 mi (2,090 km) east of the Lesser Antilles. Moving west-northwestward, the depression became Tropical Storm Ophelia on September 21, and strengthened further to reach an initial peak wind speed of 65 mph (100 km/h) on September 22. As the storm entered a region of higher wind shear it began to weaken, and was subsequently downgraded to a remnant low on September 25. The following day, however, the remnants of the system began to reorganize as wind shear lessened, and on September 27, the system became a tropical depression again. Moving northward, Ophelia regained tropical storm status early on September 28, and significantly deepened to attain its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 140 mph (220 km/h) on October 2. This peak was short-lived however as the system passed over cooler water temperatures and into an area of high wind shear, causing it to quickly weaken and undergo transition to an extratropical cyclone. Ophelia weakened to a tropical storm early on October 3, and became fully extratropical shortly after. The extratropical low was absorbed by a larger weather system on the following day.[92]

As the system made its closest approach to the Leeward Islands, Ophelia produced over 10 in (250 mm) of rainfall on some islands,[92] leading to mudslides and several road rescues.[93] Light precipitation totals and gusty winds below tropical storm force were observed on Bermuda, while storm surge and dangerous rip currents along the coast caused minimal damage.[92] In Newfoundland, heavy rainfall contributed to floods that destroyed roads and exposed the inadequacy of some repair work in the aftermath of Hurricane Igor, which struck the previous year.[94] Following Ophelia's transition into an extratropical cyclone, residents in the British Isles were urged to prepare for strong winds in excess of 75 mph (120 km/h) and precipitation accumulations up to 4 in (100 mm).[95] In the northern regions of Ireland, a combination of moisture and significantly cooler weather produced several inches of snow, leaving hundreds without electricity.[96]

Hurricane Philippe

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 24 – October 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min) 976 mbar (hPa) |

On September 23, a well-defined tropical wave emerged off the coast of Africa, associated with plentiful shower and thunderstorm activity. Moving westward and embedded within a favorable environment for development, the wave quickly became organized. On September 24, a tropical depression developed about 290 mi (465 km) south of the southernmost Cape Verde Islands. Later that day, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Philippe. Strong wind shear from upper level winds and later on from Ophelia's outflow, as well as periodic entrainment of dry air, kept the cyclone both small and disorganized. Additionally, the low-level circulation was often exposed. Because of this hostile environment, Philippe remained near the minimum for a tropical storm and briefly weakened to a tropical depression on September 28.[97]

The storm began to strengthen significantly by October 1, with an Advanced Scatterometer (ASCAT) pass on the following day confirming that Philippe was a strong tropical storm, contrary to satellite estimates. Despite high wind shear, it briefly strengthened to a hurricane on October 4 when it developed an eye feature, before weakening back to a tropical storm several hours later. Philippe re-acquired hurricane intensity on October 6 and peaked with maximum sustained winds of 90 mph (150 km/h) later that day. However, Philippe weakened to a tropical storm on October 8, before transitioning into an extratropical cyclone later that day. Early on October 9, the remnants extratropical storm was absorbed by larger low pressure area to the west of the Azores.[97]

Hurricane Rina

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 23 – October 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min) 966 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic from the west coast of Africa on October 9. After reaching the southwestern Caribbean, convection intensified near the center and organized into a broad low on October 21, possibly due to a cold front that moved into the region. After a marked increase in convection near and west of the center, a tropical depression developed early on October 23 about 60 mi (97 km) north of Isla de Providencia. The depression moved northward into a weakness in a ridge near Florida, caused by a broad mid-level trough over the Southeastern United States. Initially, the depression intensified gradually, becoming Tropical Storm Rina early on October 24. After a decrease in easterly wind shear, however, Rina rapidly deepened while crossing warm waters, reaching hurricane status at 18:00 UTC on October 24 and becoming a major hurricane about 24 hours later. Early on October 26, the storm peaked with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h).[98]

After the storm reaching peak intensity, upper-level winds and wind shear quickly became unfavorable, weakening Rina to a Category 2 later on October 26. While moving west-northwest and northward along the western periphery of the ridge, the cyclone weakened to a tropical storm on October 27. Later that day, Rina curved northward. Around 02:00 UTC on October 28, Rina struck Quintana Roo about 12 mi (19 km) southwest of Playa del Carmen with winds of 60 mph (95 km/h). The storm left little impact in the Yucatán Peninsula due to its weakened state. Rina degenerated into a remnant low late on October 28, upon emerging into the Yucatán Channel. The remnant low dissipated near the western tip of Cuba on October 29.[98] A cold front, combined with moisture from Rina, resulted in 5–7 in (130–180 mm) of rainfall across parts of South Florida in less than six hours, causing street flooding and leaving water damage in at least 160 homes and buildings in Broward County alone.[99] Farther north, two tornadoes touched down in the vicinity of Hobe Sound, one of which damaged 42 mobile homes, 2 vehicles, and a number of trees.[100]

Tropical Storm Sean

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | November 8 – November 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min) 982 mbar (hPa) |

A low pressure area of non-tropical origins developed into Subtropical Storm Sean at 06:00 UTC on November 8 about 445 mi (716 km) southwest of Bermuda. While convection and the wind field had become more symmetric, the system remained a subtropical cyclone due to the associated upper-level low. Within 12 hours, Sean separated from the low and transitioned into a tropical cyclone,[101] after developing a warm core.[102] It developed outflow and intensified due to light wind shear, combined with sufficiently warm water temperatures of at least 78.8 °F (26.0 °C). With a ridge to the northeast, the storm moved slowly to the west.[101] On November 9, an eye feature developed in association with Sean,[103] which later morphed into a ring of convection. The storm peaked with winds of 65 mph (105 km/h) on November 10 as reported by the Hurricane Hunters.[101] An approaching cold front subsequently induced higher wind shear on the cyclone as it tracked northeastward into cooler waters; this led to weakening. Sean transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on November 11. Early on the next day, it was absorbed by the cold front.[101]

Sean and its precursor produced light rainfall for several days in Bermuda.[104] Shortly after development, the Bermuda Weather Service issued a tropical storm watch, which was later upgraded to a tropical storm warning. When Sean passed near the island on November 11, it produced sustained winds of 43 mph (69 km/h), with gusts to 62 mph (100 km/h).[101] The storm produced rough seas to the east coast of Florida, which drowned one swimmer in Jensen Beach.[105] Rip currents were also observed in North Carolina.[106]

Storm names

The following list of names was used for named storms that formed in the North Atlantic in 2011. The names not retired from this list were used again in the 2017 season. This was the same list used in the 2005 season with the exceptions of Don, Katia, Rina, Sean, and Whitney, which replaced Dennis, Katrina, Rita, Stan, and Wilma, respectively. The names Don, Katia, Rina, and Sean were used for the first time this year.[107] Three names, Tammy, Vince, and Whitney, were not used during the course of the year.

Retirement

On April 13, 2012, at the 34th Session of the RA IV hurricane committee, the World Meteorological Organization retired the name Irene from its rotating name lists due to its significant impacts in the United States. It was replaced with Irma for the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season.[108]

Season effects

This is a table of all of the storms that have formed in the 2011 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, landfall(s) – denoted by bold location names – damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 2011 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category

at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arlene | June 28 – July 1 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 993 | Central America, Mexico (Veracruz), Texas, Florida | $223.4 million | 18 (4) | |||

| Bret | July 17–22 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 995 | Bahamas, Bermuda, East Coast of the United States | None | 0 | |||

| Cindy | July 20–22 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 994 | Bermuda | None | 0 | |||

| Don | July 27–30 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 997 | Cuba, Yucatán Peninsula, Northeastern Mexico, Texas | None | 0 | |||

| Emily | August 2–7 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1003 | Antilles, Florida, Bahamas | $5 million | 4 (1) | |||

| Franklin | August 12–13 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1004 | Bermuda | None | 0 | |||

| Gert | August 13–16 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 1000 | Bermuda | None | 0 | |||

| Harvey | August 19–22 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 994 | Lesser Antilles, Hispaniola, Central America (Belize), Mexico (Veracruz) | Minimal | 5 | |||

| Irene | August 21–28 | Category 3 hurricane | 120 (195) | 942 | Antilles (US Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico), Lucayan Archipelago (Bahamas), Eastern United States (North Carolina, New Jersey, New York), Eastern Canada | $14.2 billion | 49 (9) | |||

| Ten | August 25–26 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1006 | None | None | 0 | |||

| Jose | August 27–29 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1006 | Bermuda | None | 0 | |||

| Katia | August 29 – September 10 | Category 4 hurricane | 140 (220) | 942 | Lesser Antilles, East Coast of the United States, Canada, Europe | $157 million | 3 (1) | |||

| Unnamed | September 1 – September 3 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1002 | None | None | 0 | |||

| Lee | September 2–5 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 986 | Gulf Coast of the United States (Louisiana), Eastern United States | $2.8 billion | 18 | |||

| Maria | September 6–16 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 983 | Lesser Antilles, Bermuda, Newfoundland, Europe | $1.3 million | 0 | |||

| Nate | September 7–11 | Category 1 hurricane | 75 (120) | 994 | Mexico (Veracruz) | Minimal | 4 (1) | |||

| Ophelia | September 20 – October 3 | Category 4 hurricane | 140 (220) | 940 | Leeward Islands, Bermuda, Newfoundland, Europe | Minimal | 0 | |||

| Philippe | September 24 – October 8 | Category 1 hurricane | 90 (150) | 976 | None | None | 0 | |||

| Rina | October 23–28 | Category 3 hurricane | 115 (185) | 966 | Central America, Yucatán Peninsula (Quintana Roo), Cuba, Florida | $2.3 million | 0 | |||

| Sean | November 8–11 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 982 | Bermuda | Minimal | (1) | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 20 systems | June 28 – November 11 | 140 (220) | 940 | $17.39 billion | 96 (16) | |||||

See also

- Tropical cyclones in 2011

- List of Atlantic hurricanes

- Atlantic hurricane season

- 2011 Pacific hurricane season

- 2011 Pacific typhoon season

- 2011 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2010–11, 2011–12

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2010–11, 2011–12

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2010–11, 2011–12

- South Atlantic tropical cyclone

- Mediterranean tropical-like cyclone

Notes

- All damage figures are in 2011 USD, unless otherwise noted

References

- "Background Information: The North Atlantic Hurricane Season". Climate Prediction Center. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 9, 2012. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. May 25, 2020.

- Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (December 6, 2010). "Extended Range Forecast for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2011" (PDF). Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Philip J. Klotzbach; William M. Gray (December 8, 2010). "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike Probability for 2011" (PDF). Colorado State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 31, 2011. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (April 4, 2011). "April Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2011" (PDF). Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- William M. Gray; Philip J. Klotzbach (April 6, 2011). "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike Probability for 2011" (PDF). Colorado State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 2, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- "NOAA hurricane outlook indicates an above-normal Atlantic season". Climate Prediction Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 19, 2011. Archived from the original on May 21, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (May 24, 2011). "Pre-Season Forecast for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2011" (PDF). Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- "UK Met Office 2011 Atlantic tropical storm season forecast". Met Office. August 6, 2017. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- Philip J. Klotzbach; William M. Gray (June 1, 2011). "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and Landfall Strike Probability for 2011" (PDF). Colorado State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 19, 2011. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- "2011 FSU COAPS Atlantic Hurricane Season Forecast". Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies. Florida State University. Archived from the original on June 19, 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2011.

- Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (June 6, 2011). "June Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2011" (PDF). Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (July 4, 2011). "July Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2011" (PDF). Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- Johnathan Erdman (July 26, 2011). "WSI: Active Hurricane Season Ahead". Weather Services International. The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- William M. Gray; Philip J. Klotzbach (August 3, 2011). "Forecast of Atlantic seasonal hurricane activity and hurricane landfall strike probability for 2011" (PDF). Colorado State University. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Mark Saunders; Adam Lea (August 4, 2011). "August Forecast Update for Atlantic Hurricane Activity in 2011" (PDF). Tropical Storm Risk. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- "NOAA's Atlantic hurricane season update calls for increase in named storms". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 5, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Barbara Rudolph (September 21, 2011). "WSI Ups Its Named Storm Forecast to 21". Weather Services International. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Philip J. Klotzbach; William M. Gray (December 10, 2008). "Extended Range Forecast of Atlantic Seasonal Hurricane Activity and U.S. Landfall Strike Probability for 2009" (PDF). Colorado State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 12, 2009. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- "Tropical Storm Arlene lumbers across Mexico". CNN. June 30, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- "Hurricanes and Tropical Storms - Annual 2011". National Climatic Data Center. January 2012. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- John L. Beven II (August 8, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Arlene (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1–2, 4. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- Daniel Pérez González (August 5, 2011). "Para reparar daños por Arlene se requieren de 2 mil 360 millones de pesos del Fonden". El Visto Bueno (in Spanish). Archived from the original on March 30, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

- Roberto A. Grimaldo (July 21, 2011). "Daños por Arlene ascienden a 67 mdp en Tamaulipas". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Máxima García (August 19, 2011). "Pide SCT 126 mdp para carreteras en Veracruz". Imagen del Golfo (in Spanish). Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Maria D. Alcaide (August 8, 2011). "Pérdidas de $5 millones en carreteras". Primera Hora (in Spanish). Archived from the original on November 23, 2011. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- Todd B. Kimberlain; John P. Cangialosi (January 13, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Emily (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1–2, 5. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- "Lluvias dejan 3 muertos y 7.000 evacuados". Periódico Hoy (in Spanish). Associated Press. August 5, 2011. Archived from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- "Haïti: la tempête Emily a fait un mort et de nombreuses familles sinistrées". La Presse (in French). Agence France-Presse. August 8, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Eric S. Blake (July 15, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Harvey (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2, 3. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- Lixion A. Avila and John P. Cangialosi (April 11, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Irene (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2, 3. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "The 44 victims of Hurricane Irene". WPVI-TV. August 31, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- "Irene leaves a mark on Quebec". CBC News. August 29, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- "Millions in Hurricane Irene insurance claims in The Bahamas". Caribbean360. October 7, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Joaquín Carabollo (August 29, 2011). "Daños causados por Irene en el país se llevan alrededor de mil millones de pesos". Noticias SIN. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Telling the Weather Story (PDF) (Report). Insurance Bureau of Canada. June 4, 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 5, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- Gloria R. Kuilan (August 25, 2011). "Los daños ascenderían a $500 millones". El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Saul Saenz (September 4, 2011). "Tampa man killed while swimming at Ormond Beach". Bay News 9. Archived from the original on January 22, 2017. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

- Abigail Curtis (September 11, 2011). "Search suspended for man swept to sea off Monhegan Island". Bangor Daily News. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

- Stacy R. Stewart (January 16, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Katia (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- Daniel P. Brown (December 15, 2011). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Lee (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Kelli Dugan (September 5, 2011). "Tropical Storm Lee spawns tornadoes on Gulf Coast". Reuters. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Jim Forsyth (September 5, 2011). "Two dead in Texas wildfires, Perry to return". Reuters. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Jeff Masters (November 4, 2011). "Fourteen U.S billion-dollar weather disasters in 2011: a new record". Wunderground. Archived from the original on November 20, 2015. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- Storm Events Database: "Tropical Storm Maria" (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Todd B. Kimberlain (November 18, 2011). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Nate (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Event Details: Rip Current (Report). National Climatic Data Center. 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Monthly Tropical Weather Summary. National Hurricane Center (Report). September 1, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Monthly Tropical Weather Summary. National Hurricane Center (Report). September 1, 2012. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Monthly Tropical Weather Summary. National Hurricane Center (Report). October 1, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- 2011 Atlantic Basin Tropical Cyclones (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. January 26, 2012. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- David Levinson (August 20, 2008). 2005 Atlantic Ocean Tropical Cyclones (Report). National Climatic Data Center. Archived from the original on December 1, 2005. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- John L. Beven II (August 8, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Arlene (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2, 4. Retrieved August 7, 2016.

- Gaspar Romero (June 28, 2011). "Lluvias en Chiapas dejan derrumbes en carreteras y viviendas dañadas". Excélsior (in Spanish). Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- Daniel Pérez González (August 5, 2011). "Para reparar daños por Arlene se requieren de 2 mil 360 millones de pesos del Fonden". El Visto Bueno (in Spanish). Archived from the original on March 30, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

- Roberto A. Grimaldo (July 21, 2011). "Daños por Arlene ascienden a 67 mdp en Tamaulipas". El Universal (in Spanish). Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Máxima García (August 19, 2011). "Pide SCT 126 mdp para carreteras en Veracruz". Imagen del Golfo (in Spanish). Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Curtis Morgan (June 29, 2011). "Tropical Storm Arlene brings much-needed rain to South Florida". Miami Herald. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- Stacy R. Stewart (December 5, 2011). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Bret (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- Chester Robards (July 19, 2011). "Weather system dumps rain over parts of Bahamas". The Nassau Guardian. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- Owain Johnston-Barnes (July 20, 2011). "Island sees heavy rainfall after several dry months". The Royal Gazette. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- Daniel P. Brown (September 16, 2011). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Cindy (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- Michael J. Brennan (October 28, 2011). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Don (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2, 4. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- Todd B. Kimberlain; John P. Cangialosi (January 13, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Emily (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2, 5. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- "Fort-de-France durement touché par la tempête Emily". Le Point (in French). Agence France-Presse. August 3, 2011. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- Gerardo E. Alvarado-León (August 3, 2011). "Emily fue un ensayo". El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- Maria D. Alcaide (August 5, 2011). "Pérdidas de $5 millones en carreteras". Primera Hora (in Spanish). Archived from the original on August 7, 2011. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- "Lluvias dejan 3 muertos y 7.000 evacuados". Hoy (in Spanish). Associated Press. August 5, 2011. Archived from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved August 5, 2011.

- "Emily deja tres muertos en Dominicana". El Universal (in Spanish). Associated Press. August 5, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Clerna Innocent (August 5, 2011). "Haïti. Dégâts limités après le passage d'Emily". Paris Match (in French). Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- "Haïti: la tempête Emily a fait un mort et de nombreuses familles sinistrées". La Presse (in French). Agence France-Presse. August 5, 2011. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- Rob Gutro (August 10, 2011). "Hurricane Season 2011: Tropical Storm Emily (Caribbean Sea)". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- John P. Cangialosi (October 27, 2011). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Franklin (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- Bermuda Monthly Weather Summer (August 1–16, 2011) (Report). Bermuda Weather Service. August 17, 2011. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

- Robbie J. Berg (October 26, 2011). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Gert (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Eric S. Blake (July 15, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Harvey (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2, 3. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- Joy Blackburn (August 17, 2011). "Tropical wave brings high winds". Virgin Island Daily News. Archived from the original on June 10, 2015. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- Situation Report #1 - Tropical Storm Harvey makes landfall in southern Belize (as of Saturday August 20, 2011 at 9.00 p.m. EST) (PDF). Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency (Report). ReliefWeb. August 20, 2011. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- Reports Of Hurricanes, Tropical Storms, Tropical Disturbances And Related flooding During 2011 - Belize (DOC) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. 2012. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- Lixion A. Avila and John Cangialosi (April 11, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Irene (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2, 3. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- Joanisabel González (August 23, 2011). "Azote a las siembras en Maunabo y Yabucoa". El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- "Huracán "Irene" deja daños a su paso por Puerto Rico". El Regional del Zulia (in Spanish). Deutsche Presse-Agentur. August 22, 2011. Archived from the original on April 15, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

- Johanna García (August 25, 2011). "Desplazados por las lluvias aumentan a 37,743". El Día (in Spanish). Archived from the original on August 26, 2011. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- "Hay 31,900 desplazados y 85 comunidades aislada". Diario (in Spanish). August 24, 2011. Archived from the original on October 4, 2011. Retrieved August 24, 2011.

- Gloria R. Kuilan (August 25, 2011). "Los daños ascenderían a $500 millones". El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- "Hurricane Irene wreaks havoc in Haiti". Ahora. Prensa Latina. August 24, 2011. Archived from the original on August 30, 2011. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- "Haïti: la tempête Emily a fait un mort et de nombreuses familles sinistrées". La Presse (in French). Agence France-Presse. August 8, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- "More flee ahead of Irene as track forecast shifts". MSNBC. August 26, 2011. Retrieved August 25, 2011.

- Taneka Thompson (August 27, 2011). "Davis: Irene caused millions of dollars in damage to Cat Island". The Tribune. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

- "Millions in Hurricane Irene insurance claims in The Bahamas". Caribbean360. October 7, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Craig Jarvis; Bruce Siceloff (August 31, 2011). "After the winds and floods, Irene's massive toll rolls in". News & Observer. Archived from the original on October 6, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- "Hurricane Irene one year later: Storm cost $15.8 in damage from Florida to New York to the Caribbean". New York Daily News. Associated Press. August 27, 2012. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- Event Details: Tropical Storm (Report). National Climatic Data Center. 2011. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- Jonathan Allen (August 29, 2011). "Long Island residents frustrated by power outages". Reuters. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- Brian Donegan (June 12, 2016). "A Streak Not Seen Since 1900: Colin Was the 144th Consecutive Atlantic Tropical Cyclone to Not Make U.S. Landfall as a Major Hurricane". The Weather Channel. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- "Irene leaves a mark on Quebec". CBC News. August 29, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Telling the Weather Story (PDF) (Report). Insurance Bureau of Canada. June 4, 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 5, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- Richard J. Pasch (January 4, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Depression Ten (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- John L. Beven II (January 4, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Jose (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 4. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- Stacy R. Stewart (January 16, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Katia (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- "La houle cyclonique de Katia nous met en vigilance jaune" (in French). September 2, 2011. Retrieved October 13, 2016. – via France-Antilles (subscription required)

- Saul Saenz (September 4, 2011). "Tampa man killed while swimming at Ormond Beach". Bay News 9. Archived from the original on January 22, 2017. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

- Abigail Curtis (September 11, 2011). "Search suspended for man swept to sea off Monhegan Island". Bangor Daily News. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

- Post-tropical storm Katia – September 2011 (Report). Met Office. September 30, 2016. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

- "Thousands left without power as Hurricane Katia hits Ireland". TheJournal.ie. September 12, 2011. Archived from the original on January 22, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- Eric S. Blake and Todd B. Kimberlain (December 2, 2011). Tropical Cyclone Report: Unnamed Tropical Storm (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Stacy R. Stewart (September 2, 2011). Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- Daniel P. Brown (December 15, 2011). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Lee (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Kelli Dugan (September 5, 2011). "Tropical Storm Lee spawns tornadoes on Gulf Coast". Reuters. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Jim Forsyth (September 5, 2011). "Two dead in Texas wildfires, Perry to return". Reuters. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Jeff Masters (November 4, 2011). "Fourteen U.S billion-dollar weather disasters in 2011: a new record". Wunderground. Archived from the original on November 20, 2015. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- Michael J. Brennan (January 11, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Maria (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2, 3, 9, 10, 11. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Storm Events Database: "Tropical Storm Maria" (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Todd B. Kimberlain (November 18, 2011). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Nate (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2, 3. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- "Tropical Storm Nate makes landfall in Mexico's Veracruz state". Xinhua News Agency. September 12, 2011. Archived from the original on March 29, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- Michael J. Brennan (December 8, 2011). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Ophelia (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2, 3, 9, 10, 11. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- "Flooding and landslides in Dominica during heavy rainfall". The Dominican. September 28, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- "Igor damage wasn't fixed well: mayor". CBC News. October 4, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Richard James (October 3, 2011). "Britain set for heavy rain and snow as Hurricane Ophelia ends mini heatwave". Metro News United Kingdom. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- "Almost 1,0000 homes left without electricity as rain, gales and snow hits Donegal". DonegalDaily. October 6, 2011. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- Robbie J. Berg (January 3, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Philippe (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Eric S. Blake (January 26, 2012). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Rina (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 1, 2, 3. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- Summary of Heavy Rainfall/Flood Event of October 28–31 (PDF) (Report). National Weather Service Miami, Florida. November 2011. pp. 1, 2. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- EF0 Hobe Sound Tornado (PDF) (Report). National Weather Service Melbourne, Florida. November 2, 2011. pp. 1, 2. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- Lixion Avila (January 12, 2012). Tropical Storm Sean Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- Eric S. Blake (November 5, 2011). "Tropical Storm Sean Discussion Number 3". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- Eric S. Blake (November 9, 2011). "Tropical Storm Sean Discussion Number 6". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- BWS Daily Climatology Written Summary November 1 2011 to November 30 2011 (Report). Bermuda Weather Service. December 1, 2011. Archived from the original on August 8, 2007. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena with Late Reports and Corrections (PDF) (Report). 53. National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- David Horn (November 9, 2011). "Tropical Storm Sean stirs waters off NC coast". North Carolina News Network. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

- "Retired Hurricane Names Since 1954". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved November 29, 2009.

- "Irene retired from list of Atlantic Basin storm names". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. April 13, 2012. Retrieved April 25, 2013.