Hurricane Agnes

Hurricane Agnes was the costliest hurricane to hit the United States at the time, causing an estimated $2.1 billion in damage. The hurricane's death toll was 128.[1] The effects of Agnes were widespread, from the Caribbean to Canada, with much of the east coast of the United States affected. Damage was heaviest in Pennsylvania, where Agnes was the state's wettest tropical cyclone. Due to the significant effects, the name Agnes was retired in the spring of 1973.

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

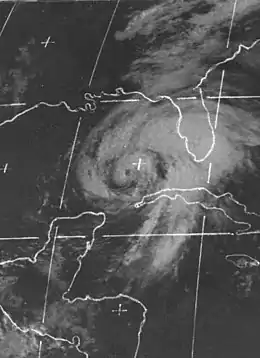

Hurricane Agnes near peak intensity in the Gulf of Mexico on June 18 | |

| Formed | June 14, 1972 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | July 6, 1972 |

| (Extratropical after June 23) | |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 85 mph (140 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 977 mbar (hPa); 28.85 inHg |

| Fatalities | 128 direct |

| Damage | $2.1 billion (1972 USD) |

| Areas affected | Yucatán Peninsula, western Cuba, Florida Panhandle, Georgia, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New York, Atlantic Canada, Iceland, Ireland, United Kingdom |

| Part of the 1972 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Agnes was the second tropical cyclone and first named storm of the 1972 Atlantic hurricane season. It developed as a tropical depression on June 14 from the interaction of a polar front and an upper trough over the Yucatán Peninsula. The storm emerged into the western Caribbean Sea on June 15, and strengthened into Tropical Storm Agnes the next day. Thereafter, Agnes slowly curved northward and passed just west of Cuba on June 17. Early on June 18, the storm intensified enough to be upgraded to Hurricane Agnes. Heading northward, the hurricane eventually made landfall near Panama City, Florida, late on June 19. After moving inland, Agnes rapidly weakened and was only a tropical depression when it entered Georgia. The weakening trend halted as the storm crossed over Georgia and into South Carolina. While over eastern North Carolina, Agnes re-strengthened into a tropical storm on June 21, as a result of baroclinic activity. Early the following day, the storm emerged into the Atlantic Ocean before re-curving northwestward and making landfall near New York City as a strong tropical storm. Agnes quickly became an extratropical cyclone on June 23, and tracked to the northwest of Great Britain, before being absorbed by another extratropical cyclone on July 6.

Though it moved slowly across the Yucatán Peninsula, the damage Agnes caused in Mexico is unknown. Although the storm bypassed the tip of Cuba, heavy rainfall occurred, killing seven people. In Florida, Agnes caused a significant tornado outbreak, with at least 26 confirmed twisters, two of which were spawned in Georgia. The tornadoes and two initially unconfirmed tornadoes in Florida alone resulted in over $4.5 million (1972 USD) in damage and six fatalities. At least 2,082 structures in Florida suffered either major damage or were destroyed. About 1,355 other dwellings experienced minor losses. Though Agnes made landfall as a hurricane, no hurricane-force winds were reported. Along the coast abnormally high tides resulted in extensive damage, especially between Apalachicola and Cedar Key. Light to moderate rainfall was reported in Florida, though no significant flooding occurred. In Georgia, damage was limited to two tornadoes, which caused approximately $275,000 in losses. Minimal effects were also recorded in Alabama, Connecticut, Delaware, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Tennessee; though one fatality was reported in Delaware. The most significant effects, by far, occurred in Pennsylvania, mostly due to intense flooding. The hurricane severely flooded the Susquehanna River and the Lackawanna River causing major damage to the Wilkes-Barre/Scranton metropolitan area. In both Pennsylvania and New Jersey combined, about 43,594 structures were either destroyed or significantly damaged. In Canada, a mobile home was toppled, killing two people.

Meteorological history

In early-mid June 1972, atmospheric conditions favored tropical cyclogenesis in the Caribbean Sea. Banded convection developed in the northwestern Caribbean Sea by June 11, though the system did not significantly organize. After an upper trough moved east, wind shear decreased, causing lower atmospheric pressures observations in Cozumel, Quintana Roo, Mexico.[2] It is estimated that a tropical depression developed by 1200 UTC on June 14, while centered over the Yucatán Peninsula, about 78 miles (126 km) southeast of Mérida, Yucatán.[3] The depression tracked eastward and entered the western Caribbean Sea on June 15.[2] Operationally, the National Hurricane Center did not initiate advisories on the depression until 1500 UTC on June 15.[4] Early on June 16 at 0000 UTC, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Agnes.[3] However, the depression was not operationally upgraded until sixteen hours later.[5]

After becoming a tropical storm on June 16, Agnes slowly curved northward and approached the Yucatán Channel.[3] Late on June 17, it was noted that projected path indicated the possibly of landfall in western Cuba.[6] However, the storm remained offshore, though it closely brushed the western tip of Cuba. At 1200 UTC on June 18, Agnes intensified into a hurricane while in the southeastern Gulf of Mexico.[3] Prematurely, the National Hurricane Center operationally upgraded Agnes to a hurricane at 0200 UTC on that day.[7] Upon becoming a hurricane, Agnes attained its maximum sustained winds of 85 mph (140 km/h), though it had not reached its minimum atmospheric pressure. Due to unfavorable conditions, Agnes leveled-off slightly in intensity and weakened to a minimal hurricane while approaching the Gulf Coast of the United States.[2] Shortly before 2200 UTC on June 19, Agnes made landfall near Cape San Blas, Florida with winds of 75 mph (120 km/h).[8]

At 0000 UTC on June 20, only a few hours after moving inland, Agnes weakened to a tropical storm. After crossing the Florida/Alabama/Georgia stateline, Agnes rapidly weakened to a tropical depression. While over Georgia, the depression curved northeastward and eventually to the east-northeast after entering South Carolina.[2] Though the storm had not dissipated, the National Hurricane Center issued its final bulletin on Agnes at 1600 UTC on June 20.[9] By early on June 21, a large extratropical trough spawned a low pressure area, which resulted in baroclinic activity. As a result, Agnes restrengthened into a tropical storm at 1800 UTC on June 21, while centered over eastern North Carolina.[2] Three hours later, the National Hurricane Center noted decreasing atmospheric pressures, and indicated that winds had reached gale-force winds and once again upgraded Agnes to a tropical storm.[10] By early on June 22, Agnes emerged into the northwestern Atlantic Ocean, where it continued to re-intensify. At 1200 UTC, Agnes reached its minimum atmospheric pressure of 977 mbar (28.9 inHg), as reported by a reconnaissance aircraft. However, maximum sustained winds were at only 70 mph (110 km/h).[2][3] Late on June 22, Agnes made its final landfall on Long Beach, New York, on Long Island, with winds of 65 mph (100 km/h).[11]

Agnes began its long life as an extratropical cyclone once cold air invaded its circulation late on June 22, completing its extratropical transition on the next day. The system looped across south-central Pennsylvania on June 23 and then looped across southern Ontario on June 25. It spawned a tornado in Maniwaki, Ontario early that day, which killed two and injured 11 people. The cyclone sped east-northeast, reaching Cape Breton on June 27 before intensifying as it re-entered the North Atlantic. After moving as far north as the 61st parallel while crossing the 25th meridian west on the morning of June 29, Agnes turned southeastward. Its central pressure bottomed out near 980 millibars (29 inHg) towards 0000 UTC on June 30. Between July 1 and July 3, the long-lived system looped between Ireland and Iceland while weakening once more. The system turned northeast, strengthening one more time while accelerating across the Hebrides on July 4 through 5. A stronger system moving in from the west finally absorbed Agnes on July 6, while located to the southeast of Iceland.[12]

Preparations

By 2200 UTC on June 17, the National Weather Service issued gale warnings and a hurricane watch for the Straits of Florida and the Florida Keys from Key West to Dry Tortugas.[13] On the following day at 1600 UTC, another hurricane watch was put into effective from Cedar Key to Pensacola. In addition, the gale warnings in the Florida Keys were extended to include areas from Fort Myers Beach to Clearwater.[14] At 2200 UTC on June 18, a hurricane warning became effective from St. Marks to Panama City.[15] The gale warnings which were in effect for the Florida Keys and Fort Myers Beach to Clearwater was discontinued at 1000 UTC on June 19.[16] It is likely that the hurricane warning was discontinued after the National Hurricane Center downgraded Agnes to a tropical storm at 2200 UTC on June 20.[8] Two hours later, all gale warnings along the West Coast of Florida were discontinued.[17]

Impact

| Area | Deaths |

|---|---|

| Canada | 2 |

| Cuba | 7 |

| Florida | 9 |

| North Carolina | 2 |

| Virginia | 13 |

| Delaware | 1 |

| Maryland | 19 |

| New Jersey | 1 |

| New York | 24 |

| Pennsylvania | 50 |

| Total | 128 |

United States

In the United States, Agnes affected 15 states and the capital area of Washington D.C.. Almost 110,000 houses were ruined by Agnes, 3,351 of which were destroyed. In addition, 5,211 mobile homes were either damaged or completely destroyed. Farm buildings and small businesses also suffered extensively, with 2,226 and 5,842 structures experiencing major losses or were destroyed. Of the 128 fatalities caused by Agnes, 119 occurred in the United States. All of the damage estimates associated with Agnes were within the country.

Agnes was, at the time, the costliest hurricane in the history of the United States, though it has since been surpassed by numerous other storms.

Florida

Upon landfall, Agnes produced abnormally high tides along much of the Florida coastline. The highest tides reported were at Cedar Key, reaching 7 feet (2.1 m) above normal sea levels. The second largest waves were 6.4 feet (2.0 m), recorded at Apalachicola. In contrast, few observations of high tides along the east coast of Florida exist; the highest reported was 3 feet (0.91 m) above average in Jacksonville.[2] In Alligator Point, at least 16 homes were swept off their foundations. Six bridges connecting Cedar Key to the mainland areas of Florida were submerged. In addition, a bridge from Coquina Key to St. Petersburg was also underwater due to high tides.[18] Nearly the entire state of Florida reported rainfall, though it was usually in the light to moderate range. Among the highest amounts of precipitation recorded were 8.97 inches (228 mm) in Naples, 8.43 inches (214 mm) in Big Pine Key, 7.3 inches (190 mm) in the Everglades, and 7.17 inches (182 mm) in Tallahassee.[2] Near Okeechobee, larger amounts of rainfall may have occurred, though there were no specific observations in that vicinity.[19]

.jpg.webp)

Though Agnes made landfall as a hurricane, no reports of hurricane-force winds exist. However, several locations observed tropical storm force winds. The highest sustained winds and gusts were 52 and 69 mph (84 and 111 km/h), both recorded at the Kennedy Space Center. Other reports of at least tropical storm force sustained winds were at 39 mph (63 km/h) in Crestview and Jacksonville, 42 mph (68 km/h) in Flamingo, 43 mph (69 km/h) in Key West, and two observations of 40 mph (64 km/h) in Panama City.[2] Throughout the state, Agnes spawned at least 15 tornadoes, while several tornadoes were operationally unconfirmed. Initially referred to as a "windstorm", one of those twisters destroyed 50 mobile homes and a fishing camp in Okeechobee, as well as caused six fatalities. Another significant tornado occurred in Cape Canaveral, which destroyed two homes and 30 trailers; it also damaged 20 houses and the Port Canaveral Coast Guard station. Overall, more than 100 people were left homeless and caused 23 injuries and over $500,000 in damage. The costliest tornado was also spawned in Brevard County and it destroyed 44 planes at the Merritt Island Airport and an apartment building. In addition, several houses in a nearby subdivision were also damaged. Losses from this tornado are estimated at $3 million.

Due to a combination of high tides, rainfall, winds, and tornadoes, 96 dwellings were destroyed, while about 1,802 suffered damage to some degree. The destruction of 177 mobile homes was reported and 374 others were significantly damaged. Furthermore, 988 small businesses in the state were either destroyed or had major damage.[20] Eight counties in Florida reported at least $1 million in damage, including $12.1 million in Pinellas, $7.1 million in Sarasota, $4.1 million in Brevard, $3.1 million in Pasco, $2 million in Manatee, $1.4 million in Wakulla and Franklin, $1.3 million in Monroe, and $1 million in losses in Hillsborough Counties.[21] Although the damage toll estimated by the National Hurricane Center was at $8.243 million,[22] the National Climatic Data Center noted that at least $39 million in losses were reported.[21] In addition, nine fatalities were reported in Florida.[22]

Southeastern United States

In the states immediately to the north of Florida, impact was relatively minor. Rainfall was generally light in Georgia, though peaking at 8.55 inches (217 mm) in Brunswick. Other locations that reported precipitations include 4.54 inches (115 mm) in Albany, 3.95 inches (100 mm) in Savannah, and 3.18 inches (81 mm) in Macon.[2] During the tornado outbreak, two of the tornadoes were spawned in Georgia. The tornado in Pierce County caused $25,000 in damage and one injury.[23] Losses were more significant from the twister in Coffee County, reaching $250,000.[24] One mobile home in Georgia suffered significant damage, though it is unknown if this was related to the tornadoes.[20] Though the damage from both tornadoes combined was about $275,000,[23][24] the National Hurricane Center notes only $205,000 in losses.[22]

In Alabama, tides up to 1.3 feet (0.40 m) above normal were reported in the Mobile Bay area. Though rainfall only reached 3.93 inches (100 mm) and 1.08 inches (27 mm) in Dothan and Mobile,[19] precipitation from the storm in the state of Alabama peaked at 7.67 inches (195 mm) in Headland. Damage in the state was minor, though low-lying streets in the Gulf Shores were flooded.[25]

In some areas of South Carolina, the storm dropped as much as 9.5 inches (240 mm) of rain in less than 36 hours. As a result, several rivers flooded. Along the Pee Dee River, pastures, small grains, and soy bean crops near Cheraw suffered major damage; similar effects occurred along the Congaree River near Columbia, though damage was lesser. In Greenville, damage to basements, streets, and water systems occurred after the Reedy River overflowed.[26] Damage in South Carolina was minor, totaling to only $50,000.[22]

Effects were very minimal in Tennessee and limited to light rainfall in the eastern portions of the state, generally reaching no more than 3 inches (76 mm).[19] The highest amount of precipitation recorded was 4.59 inches (117 mm) in Unicoi.[27]

Virginia

.jpg.webp)

In Richmond, four people drowned after their car plunged into the swollen James River.[28] A train bound for Washington D.C. stopped due to flooding in Richmond, which temporarily stranded 537 passengers.[29] The Peak Creek in western Virginia overflowed its banks, flooding a low-income housing area of Pulaski with water up to rooftops.[30] At the height of the flooding, over 600 miles (970 km) of highways were submerged, resulting in $14.8 million in damage to roads in the state. Severe damage also occurred to sewer and water facilities, totaling to $34.5 million.[31] 95 houses were destroyed and 4,393 others were damaged, while 125 mobile homes were destroyed and another were significantly affected. Additionally, 205 small businesses were either damaged or destroyed. The Interstate 95 (I-95) Purple Heart Bridge over northern Virginia's Occoquan River was severely damaged and closed when rammed by a large barge carried by floodwaters.[32] In the Washington DC suburbs, the Alexandria reservoir Lake Barcroft emptied when its dam was undermined and breached.[33]

Overall, flooding was described as "the worst in 50 years".[28] In Virginia alone, 13 fatalities and $125.9 million in losses were reported.[22]

Maryland

In Baltimore, a woman's car was swept off a highway; firemen in rowboats were able to rescue her, but her three children drowned.[34] In the state of Maryland, damage totaled to $110 million and 19 fatalities were reported.

The hardest hit area was the Patapsco River valley, with widespread destruction of buildings, roads, and railroads in the state park, at Daniels including its mill,[35] at Ellicott City, and Oella. The flooding was first reported in the early morning hours of June 22 and water was reported as high as 40 feet (12 m) above normal.[36] River Road along the Patapsco was almost completely washed out. More than 900 people were evacuated from their homes. National guard helicopters were used to rescue workmen from the roof of the Daniels' plant. In Elkridge, a family of six was forced from their home and they attempted to reach high ground in a small boat. It capsized and all six held onto the boat for several hours until it reached more shallow water.

In Howard County, a total of 704 county residents were left homeless. More than 80 homes in the Ellicott City area were damaged and 72 homes in Elkridge were affected. In Laurel, the 9th Street Bridge crossing the Patuxent River was washed away by flood waters. In Anne Arundel County, all roads linking the county with Baltimore city or county were closed (including the Baltimore Beltway) as were all roads "near the Patuxent River" including Waysons Corner where over 300 homes were evacuated.[32] The Patapsco flooded residential homes in parts of the county's North Linthicum, Pumphrey, and Belle Grove Road, Brooklyn Park neighborhoods.[32]

The Gwynn Oak Amusement Park closed after suffering severe damage from flooding when Hurricane Agnes caused Gwynns Falls to overflow. In 1974, the park's rides were auctioned off. The carousel was moved and is still in operation on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

A popular footbridge in the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park which led across a branch of the Potomac River to an overlook of Great Falls was washed away and not rebuilt until 1996.[37]

As a result of Agnes' rains, Conowingo Dam, astride the Susquehanna River just north of the Chesapeake Bay, recorded its all-time highest flow rate and stream heights.[38] Before the river crested, the water came within feet of overtopping the dam. As the dam's normal flood control devices seemed unable to cope, engineers had placed charges to blow out a section of the dam to prevent a catastrophic failure.

Pennsylvania

In Pennsylvania, heavy rainfall was reported, with much of the state experiencing more than 7 inches (180 mm) of precipitation. Furthermore, a large swath of rainfall exceeding 10 inches (250 mm) was reported in the central part of the state. Overall, the rains peaked at 19 inches (480 mm) in the western portions of Schuylkill County.[19] As a result, Agnes is listed as the wettest tropical cyclone on record for the state of Pennsylvania. Overall, more than 100,000 people were forced to leave their homes due to flooding. Some buildings were under 13 feet (4.0 m) of water in Harrisburg.[39] At the Governor's Mansion, the first floor was submerged by flood waters. Hundreds were trapped in their homes in Wilkes-Barre due to the overflowing Susquehanna River. At the historic cemetery in Forty Fort, 2,000 caskets were washed away, leaving body parts on porches, roofs, and in basements. In Luzerne County alone, 25,000 homes and businesses were either damaged or destroyed. Losses in that county totaled to $1 billion.[40] In Chadds Ford Township in Delaware County, the Brandywine Creek crested at 16.5 feet (5.0 m), sending flood waters into the city. Water poured into the first floor of an art museum in Chadds Ford Township, which threatened at least $2.5 million in N.C. Wyeth paintings, though they were quickly moved to the upper floors. Along the Allegheny River, it was above flood stage in some low-lying areas. During the height of the storm, the river was rising at about 7 inches (180 mm) per hour.[39] In Reading, the Schuylkill River reached a record flood of 31 feet 6 inches (9.60 m). Hundreds of people were evacuated and over a hundred homes destroyed. Floods reached as far inland as 3rd street in the heart of the city.[41]

More than one hundred Harrisburg YMCA campers and staff were evacuated using two CH-47 Chinook helicopters flown by the National Guard at Camp Shikellimy located downstream of DeHart Dam in Middle Paxton Township. Additionally, 36 Girl Scouts were rescued by state police while at a camp in York. A bridge collapsed in Danville, which caused two diesel locomotives and several freight cars to fall into a swollen creek.[29] In the state of Pennsylvania, more than 68,000 homes and 3,000 businesses were destroyed. Due to the destroyed houses, at least 220,000 people were left homeless.[40] The damage and death toll was the highest in Pennsylvania, with 50 fatalities and $2.3 billion in losses in that state alone.

On June 26, 1972, three news correspondents and the pilot were killed in a helicopter crash in Harrisburg, where they had been covering the flooding. The victims were Del Vaughn of CBS News and Sid Brenner and Louis Clark of WCAU in Philadelphia, and the pilot, Mike Sedio. The helicopter lost its rotor some three hundred feet (90 m) above the Capital City Airport, crashed, and exploded on the runway.[42]

New York

Olean, Elmira, and Corning, as well as many other Southern Tier towns, were severely flooded. Sections of the Erie Lackawanna Railroad main line between Hornell and Binghamton were severely damaged. It is mainly regarded as the death of the Erie Lackawanna Railroad since the costs of damages were high and put the final dagger into the company. Flooding in the upper Allegheny River basin was particularly exacerbated by the construction of the Kinzua Dam less than a decade prior; several towns in Cattaraugus County suffered extensive road and bridge damage that, four decades later, has yet to be repaired, with the state and local governments opting to abandon creek and river crossings instead of reconstruct them. The dam succeeded in preventing further damage downstream in western Pennsylvania, and much of the flood-prone areas in the Allegheny Reservoir region had already been cleared of residents in preparation for the dam's construction.

In Elmira, porches and garages were ripped loose, the Walnut St. bridge was carried away, Maple Ave. to Notre Dame High School was "underwater", and on S. Main St., Gerould's Pharmacy at W. Hudson was engulfed by 10 feet 3 inches (3.12 m) of water.

Hornell's damage was minimal largely due to the protection of two dam systems installed after the devastating 1935 flood. Both the Arkport and Almond Dams saved Hornell from the level of damage found in neighboring communities. Three US Army Corps of Engineers were killed in Hornell when their helicopter came in contact with power lines over Crosby Creek.

The height of the floodwaters has been marked in the entrance to the Corning Museum of Glass, showing that much of the museum was under water to a height of about 1.6 m above the floor, causing substantial damage to the collection and archives. Parts of Corning were under more than 3 m of flood waters.

West Virginia and Ohio

Rainfall in West Virginia was generally light, though heavier in the Eastern and Northern Panhandles of the state.[19] Precipitation peaked at 7.94 inches (202 mm) in Berkeley Springs. 108 houses were destroyed and 1,558 others suffered damage. Furthermore, 118 mobile homes were destroyed and 91 were significantly affected. 10 farm buildings reported major losses, while 18 small businesses were either damaged or destroyed.[20] In the state of West Virginia, no fatalities were reported and damage was slightly more than $7.7 million.[22]

Although no reports of abnormally high winds or rainfall exists in Ohio,[2] the storm caused minor damage to about 302 dwellings and severely affected at least three houses. In addition, at least 100 mobile homes suffered major damage.[20] Northeasterly winds from the storm waves reaching a height of 15 feet (4.6 m) along the shore of Lake Erie and also caused the water level to rise by 3.5 feet (1.1 m). Houses, cars, boats, buildings, ships, and docks in the vicinity of Lake Erie were damaged.[26] Overall, losses in Ohio totaled to at least $4 million.[22][26]

Elsewhere in the United States

While approaching Delaware, Agnes produced tides about 1.5 feet (0.46 m) above normal at the Indian River Inlet. High winds were also reported in the state, and at the Dover Air Force Base, a wind gust as high as 67 mph (108 km/h) was reported.[2] Rainfall was generally light, peaking at 7.6 inches (190 mm) in Middletown.[43] Street flooding was reported and basements in low-lying area were flooded, though damage in Delaware was minimal.[44] One fatality occurred in that state.[2] In the Washington, D.C. area, moderate rainfall was reported, with precipitation amounts peaking at 13.65 inches (347 mm) at the Washington Dulles International Airport.[2] Significant flooding occurred and it was described as the worst in at least 44 years. In the Georgetown section, waterfront streets along the Potomac River were submerged in as much as 7 feet (2.1 m) of water.[45] The Rock Creek also overflowed its banks, which sent about 10 feet (3.0 m) of water onto the Rock Creek Parkway. As a result, at least 100 cars were abandoned and several motorists required rescuing by police.[39] No national monuments were affected by flood waters.[45] However, about 350 dwellings in Washington, D.C. suffered minor damage.[20] At the White House, reporters noted wet carpets in the press room of the basement floor.[39]

Though the storm passed just west of some areas in New England, minimal impact in that region of the United States. In Connecticut, winds were well below tropical storm force, although a wind gust of 46 mph (74 km/h) was reported in Hartford. Rainfall in the state was light, peaking at 1.62 inches (41 mm), also recorded in Hartford.[2] Along the coast of Connecticut, high tides and heavy rainfall flooded coastal roads and basements. High tides occurred along the coastline of Rhode Island, reaching 3.2 feet (0.98 m) above normal in Providence.[2] In combination with rainfall and high tides, some coastal roads were flooded. Strong winds felled trees and numerous limbs in Massachusetts, causing power outages and property damage in the western and central portions of the state. One home in Great Barrington was struck by a tree; a similar incident occurred in Milford. High winds in southern and eastern Vermont knocked over trees and snapped off limbs, which resulted in scattered power outages, roads being blocked, and minor property damage. In Mendon, a tree fell on a house, while two cars were damaged after being struck by limbs. Similar conditions occurred in New Hampshire, albeit effects were lesser.[26]

Elsewhere

As a precaution, more than 8,000 people in western Cuba, including on Isla de la Juventud (Isle of Pines), were evacuated.[46] In western Cuba, Agnes dropped heavy rainfall, peaking at 16.76 inches (426 mm) on Isla de la Juventud. At Cape San Antonio, the westernmost point in Cuba, precipitation reached 15.32 inches (389 mm).[2] Due to high winds and flooding, at least 97 houses were destroyed and another 270 were damaged. In the Pinar del Río Province, the cities of Guane and Mantua were isolated by swollen rivers. It was also reported that extensive crop damage occurred in low-lying areas.[46] Overall, seven fatalities occurred in Cuba, though the damage toll is unknown.[47] However, some sources claim Agnes caused 16 fatalities and reported 24 people missing.[48]

In Canada, Hurricane Agnes gave heavy rains and winds over southern Ontario and southern Quebec, causing numerous floodings around Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. In the town of Maniwaki, Quebec, the storm toppled a mobile home, killing two people.[49]

Aftermath

Following the storm, President of the United States Richard Nixon declared 14 counties in Florida as a disaster area, including: Brevard County, Dixie County, Franklin County, Hendry County, Hillsborough County, Lee County, Levy County, Manatee County, Monroe County, Okeechobee County, Pasco County, Pinellas County, Sarasota County, and Wakulla County.[50] In Panama City, Florida, where over 25,000 tourists evacuated, effects were not significant. As a result, the city lost millions of dollars from tourism, which led the officials of Panama City to file a $100 million lawsuit against the National Weather Service. Officials in that city believed that the National Weather Service and other media outlets made "exaggerated and erroneous" forecasts and reports on the storm.[51] Nixon also declared the states of Florida, Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New York as disaster areas. Twenty of Maryland's 24 counties were declared a disaster area.

Agnes had a devastating impact on the already-bankrupt railroads in the northeastern United States, as lines were washed out and shipments were delayed:

- The Erie Lackawanna Railway (EL) estimated that damage between Binghamton and Salamanca, New York, amounted to $2 million. EL filed for Chapter 77 bankruptcy.

- The Penn Central Railroad sustained nearly $20 million in damages

The resulting cost of repairing the damage was one of the factors leading to the creation of the federally financed Conrail.

The severe floods near Lawrenceville, Pennsylvania, were the catalyst for the construction of the Tioga Reservoir in 1973. The flooding in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, and the adjacent town of Kingston led to the construction of a levee system that in 2006 successfully prevented massive flooding and, in the same year, was deemed very safe and protective by the Army Corps of Engineers. The levee also protected the area from the remnants of Tropical Storm Lee and Hurricane Irene in 2011, with the water cresting just barely below the height of the structure. Conversely, the existing Kinzua Dam, built against the wishes of the Seneca Nation of New York, spared much of Western Pennsylvania from the worst flooding, by filling the Allegheny Reservoir to capacity.

Footage is included in the 1987 film Disasters-Anatomy of Destruction, hosted by George Kennedy.

Retirement

Because of extensive damage and severe death tolls, the name Agnes was retired following this storm, and will never again be used for another Atlantic hurricane.[52] Because the tropical cyclone naming lists were changed in 1979, there was no replacement name selected.

See also

- List of Atlantic hurricanes

- List of wettest tropical cyclones in the United States

- Timeline of the 1972 Atlantic hurricane season

- List of Delaware hurricanes

- Hurricane Sandy – made landfall in southern New Jersey as an extratropical cyclone in late October 2012

- Hurricane Hermine (2016) – took a similar path in early September 2016

References

- Hurricane Agnes 40th Anniversary (Report). NOAA. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- R. H. Simpson and Paul J. Herbert (April 1973). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1972" (PDF). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 25, 2011. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- "Hurricane Agnes – Official Track". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. 1972. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- Paul Hebert (June 15, 1972). "National Hurricane Center Bulletin 11:30 a.m. EDT Thursday". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- Arnold Sugg (June 16, 1972). "National Hurricane Center Advisory Number 1 Tropical Storm Agnes". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- Arnold Sugg (June 17, 1972). "National Hurricane Center Bulletin Tropical Storm Agnes". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- Robert Simpson (June 18, 1972). "National Hurricane Center Hurricane Bulletin Agnes 10 p.m. Saturday". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- Joseph Pelissier (June 19, 1972). "National Hurricane Center Tropical Storm Advisory Number 14 Agnes". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- Joseph Pelissier (June 20, 1972). "National Hurricane Center Bulletin Tropical Depression Agnes 12:00 p.m. EDT Tuesday". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- Neil Frank (June 21, 1972). "Tropical Cyclone Discussion – Storm Agnes". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- David M. Roth (2011). "CLIQR database". Camp Springs, Maryland: Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- Richard W. Schwerdt, ed. (November 1972). "Smooth Log, June 1972". Mariners Weather Log. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 16 (6): 378.

- Robert Simpson (June 17, 1972). "National Hurricane Center Hurricane Advisory Number 6". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- Robert Simpson (June 18, 1972). "National Hurricane Center Hurricane Advisory Number 9 Agnes". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- Joseph Pelissier (June 18, 1972). "National Hurricane Center Hurricane Advisory Number 10 Agnes". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- Raymond Kraft (June 19, 1972). "National Hurricane Center Advisory Number 12". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- John Hope (June 20, 1972). "National Hurricane Bulletin Tropical Storm Agnes". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- Staff Writer (June 19, 1972). "Agnes Lashes Florida Coast". Pittsburgh Press. Panama City, Florida. United Press International. pp. 1 and 3. Retrieved January 10, 2012.

- David M. Roth (September 30, 2006). "Hurricane Agnes – June 14–25, 1972". Camp Springs, Maryland: Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved January 8, 2012.

- "Impact Of Hurricane Agnes On Property". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. 1972. Retrieved January 8, 2012.

- "Narrative Summary for Monthly Climatological Data – Florida". National Climatic Center. July 12, 1972. Retrieved January 8, 2012.

- "U.S. Deaths And Damage Attributed To Agnes". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. December 1, 1972. Retrieved January 8, 2012.

- National Centers for Environmental Information. Storm Event Report for F1 Tornado in Coffee County, Georgia. Storm Events Database (Report). Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- National Centers for Environmental Information. Storm Event Report for F2 Tornado in Coffee County, Georgia. Storm Events Database (Report). Asheville, North Carolina: National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- Robert Ferry (July 12, 1972). "Final Report For Alabama – Hurricane Agnes". National Weather Service Birmingham, Alabama. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- "June 1972" (PDF). Storm Data. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 14 (6): 76, 82, 86, 92, 96. 1972. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 3, 2019. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Southeastern United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- Staff Writer (June 22, 1972). "Agnes Causes Shiver Across Wide Area". The Windsor Star. Windsor, Ontario. Retrieved January 18, 2012.

- "Thousands Flee as Agnes Rips 11-State Area". Miami Herald. June 23, 1972. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- Staff Writer (June 22, 1972). "Hurricane Roars Back in Virginia". The Spokesman-Review. Richmond, Virginia. Associated Press. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- Curtis Crockett (July 24, 1972). "Report on Hurricane Agnes". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- "Flash floods kill 4 in Maryland; thousands stranded in Virginia". The Evening Capital. Annapolis, Maryland. June 22, 1972. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- "LBWID Facts about the Lake and Dam". Lake Barcroft Watershed Improvement District. State of Virginia. Archived from the original on September 6, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

[WID] was formed in 1973 in the wake of the destruction of the Lake by the failure of the dam as a result of tropical Storm Agnes in 1972.

- Staff Writer (June 26, 1972). "Thousands Flee From Homes, 29 Die As Agnes Sweeps Eastern Seaboard". Miami Herald. Miami, Florida. United Press International. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- "Patapsco Valley State Park History". Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved November 5, 2015.

- Riordan, Penny. "40 Years Ago, Patapsco Devastated By Agnes Flood". patch.com. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- "Along the Towpath" (PDF). C&O Canal Association. September 1996. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- "Historical Crests for Susquehanna River at Conowingo Dam". Archived from the original on February 5, 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2012.

- Herald Wire Services (June 24, 1972). "Flood Situation State by State". Miami Herald. Miami, Florida. United Press International. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- Bill O'Boyle (June 22, 2009). "Agnes now a flood of memories". Times Leader. Archived from the original on January 2, 2014. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- Mike Reinert (October 6, 2010). "Hurricane Agnes Flood in Reading, PA". Berks Time Train. WFMZ-TV.

- "Four Die in 'Copter Crash, June 27, 1972". The Morning Herald, Uniontown, Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on June 7, 2014. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- Roth, David M; Weather Prediction Center (2012). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Mid-Atlantic United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- W. J. Moyer (July 6, 1972). "Tropical Storm Agnes, June 21–23, 1972". University of Maryland, College Park. Retrieved January 9, 2012.

- Staff Writer (June 26, 1972). "Flood Damage Costs Amount". The Bonham Daily Favorite. Bonham, Texas. United Press International. Retrieved January 9, 2012.

- Staff Writer (June 18, 1972). "Agnes Ranked As Hurricane". Reading Eagle. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. Retrieved January 9, 2012.

- "Hurricane History". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. 2008. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- "Principales Eventos Pluviales Sobre Cuba En El Periodo 1963 – 2006". Havana, Cuba: CubAgua. 2006. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- Ève Christian. "Page d'histoire — juin". La Météo au Quotidien (in French). Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- United States Department of Homeland Security (May 23, 2005). "Florida Tropical Storm Agnes – Major Disaster Declared June 23, 1972 (DR-337)". Federal Emergency Management Agency. Archived from the original on January 3, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2012.

- Frank Sikora (June 26, 1972). "Instead of praying, irked resort sues". The Birmingham News. Panama City Beach, Florida. Retrieved January 9, 2012.

- Faq : Hurricanes, Typhoons, And Tropical Cyclones Archived 2006-12-06 at the Wayback Machine

Books

- J. F. Bailey, J. L. Patterson, and J. L. H. Paulhus. Geological Survey Professional Paper 924. Hurricane Agnes Rainfall and Floods, June–July 1972. United States Government Printing Office: Washington D.C., 1975.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hurricane Agnes. |

- National Hurricane Center web site for Agnes. This US government site is in the public domain.

- HPC Rainfall Site for Agnes

- FAQ: Hurricanes, Typhoons, and Tropical Cyclones, NOAA, retrieved January 26, 2006.

- The short film "Welcome to Corning, New York: Tropical Storm Agnes Flood (1972)" is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- Watch Disasters-Anatomy of Destruction (1987) on the Internet Archive

| Preceded by Camille (Tied with Betsy) |

Costliest Atlantic hurricanes on Record 1972 |

Succeeded by Alicia |