2020–2021 United States racial unrest

The 2020–2021 United States racial unrest is an ongoing wave of civil unrest, comprising protests and riots, against systemic racism towards black people in the United States, notably in the form of police violence. It is partly facilitated by the nationwide Black Lives Matter movement, and was initially triggered by the killing of George Floyd during his arrest by Minneapolis police officers on May 25, 2020. Following the death of George Floyd, unrest broke out in the Minneapolis–Saint Paul area on May 26, and quickly spread across the country and the world. Within Minneapolis, widespread property destruction and looting occurred, including a police station being overrun by demonstrators and set on fire, causing the Minnesota National Guard to be activated and deployed on May 28. After a week of unrest, over $500 million in property damage was reported in the Minneapolis–Saint Paul area and two deaths had been linked to the riots.[8][9][10][11]

| 2020–2021 United States racial unrest | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top:

| |

| Date | May 25, 2020 – present (8 months, 1 week and 6 days) |

| Location | |

| Caused by | Several deaths related to police activity, notably the killing of George Floyd while being arrested by the Minneapolis Police,[1] police brutality,[1] lack of police accountability,[1] inequality and racism[2] |

| Methods | Protests, demonstrations, riots, looting, civil disobedience, civil resistance, strike action |

| Status | Ongoing

|

| Concessions given |

|

| Casualties | |

| Death(s) | At least 25[4] |

| Injuries | 400+ law enforcement officials and an unknown number of civilians[5] |

| Arrested | Over 14,000 (as of June 27, 2020)[6] |

| Damage | $1–2 billion insured damages (as of September 17, 2020)[7] |

Further unrest quickly spread throughout the United States, sometimes including rioting, looting, and arson. By early June, at least 200 American cities had imposed curfews, while more than 30 states and Washington, D.C, had activated over 62,000 National Guard personnel in response to unrest.[12][13][14] By the end of June, at least 14,000 people had been arrested at protests.[15][16][17] Polls have estimated that between 15 million and 26 million people had participated at some point in the demonstrations in the United States, making them the largest protests in United States history.[18][19][20] It was also estimated that between May 26 and August 22, around 93% of protests were "peaceful and nondestructive".[21][22] According to several studies and analysis, protests have been overwhelmingly peaceful, with police and counter-protesters sometimes starting violence.[23][24][25] According to a September 2020 estimate, arson, vandalism and looting caused about $1–2 billion in insured damage between May 26 and June 8, making this initial phase of the George Floyd protests the civil disorder event with the highest recorded damage in United States history.[7][26]

There has also been a large concentration of unrest around Portland, Oregon, which has led to the Department of Homeland Security deploying federal agents in the city from June onward. The move was code named Operation Legend, after 4 year old LeGend Taliferro, who was shot and killed in Kansas City.[27] Federal forces have since also been deployed in other cities which have faced large amounts of unrest, including Kansas City and Seattle.[28][29][30][31] More localized unrest reemerged in several cities following incidents involving police officers, notably following the shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, which led to protests and riots in the city. The protests have led to requests at the federal, state and municipal levels intended to combat police misconduct, systemic racism, qualified immunity and police brutality in the United States.[32][33] A wave of monument removals and name changes has taken place throughout the world, especially in the United States. This itself has sparked conflict, between left-wing and right-wing groups, often violent. Several far-right groups, including civilian militias and white supremacists, have fought with members of "a broad coalition of leftist anti-racist groups" in street clashes.[34]

The racial unrest precipitated a national American cultural reckoning on topics of racial injustice. Public opinion of racism and discrimination quickly shifted in the wake of the protests, with significantly increased support of the Black Lives Matter movement and acknowledgement of institutional racism, i.e. systemic advantages and disadvantages due to race.[35][36][37] Demonstrators revived a public campaign for the removal of Confederate monuments and memorials as well as other historic symbols such as statues of venerated American slaveholders and modern display of the Confederate battle flag.[38][39] Public backlash widened to other institutional symbols, including place names, namesakes, brands and cultural practices. Anti-racist self-education became a trend throughout June 2020 in the United States. Black anti-racist writers found new audiences and places on bestseller lists. American consumers also sought out black-owned businesses to support. The effects of American activism extended internationally, as global protests destroyed their own local symbols of racial injustice. Multiple media began to refer to it as a national reckoning on racial issues in early June. By the beginning of July, The Washington Post was running a regularly collecting new stories of the day related to "America's Racial Reckoning".[35][36][37][40]

Background

Police brutality in the United States

Frequent cases of police misconduct and fatal use of force by law enforcement officers[41] in the United States, particularly against African Americans, have long led the civil rights movement and other activists to protest against the lack of police accountability in incidents involving excessive force. Many protests during the civil rights movement were a response to police brutality, including the 1965 Watts riots which resulted in the deaths of 34 people, mostly African Americans.[42] The largest post-civil rights movement protest in the 20th Century was the 1992 Los Angeles riots, which were in response to the acquittal of police officers responsible for excessive force against Rodney King, an African American man.[43]

In 2014, the shooting of Michael Brown by police in Ferguson, Missouri resulted in local protests and unrest while the death of Eric Garner in New York City resulted in numerous national protests. After Eric Garner and George Floyd repeatedly said "I can't breathe" during their arrests, the phrase became a protest slogan against police brutality. In 2015 the death of Freddie Gray in Baltimore police custody resulted in riots in the city and nationwide protests as part of the Black Lives Matter movement.[44] Several nationally publicized incidents occurred in Minnesota, including the 2015 killing of Jamar Clark in Minneapolis; the 2016 killing of Philando Castile in Falcon Heights;[45] and the 2017 killing of Justine Damond. In 2016, Tony Timpa was killed by Dallas police officers in the same way as George Floyd.[46] In March 2020, the killing of Breonna Taylor by police executing a no knock warrant at her Kentucky apartment was also widely publicized.[47] However, it was later revealed the warrant was not a no knock warrant in released police documents[48] and the reports were redacted.[49]

According to The Washington Post database of every fatal shooting by an on-duty police officer in the United States, as of August 31, 2020, 9 unarmed black people had been shot by police in 2020. As of that date the database lists four people of unknown race, 11 white people, 3 Hispanic people, and 1 person of "other" race who were shot while unarmed.[50] Black people, who account for less than 13% of the American population, are killed by police at a disproportionate rate, being killed at more than twice the rate of white people.[50]

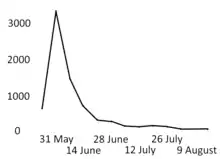

According to a data set and analysis which was released by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED) at the beginning of September, there were more than 10,600 demonstration events across the country between May 24 and August 22 which were associated with all causes: Black Lives Matter, counter-protests, COVID-19-pandemic-related protests, and others.[22] After Floyd's killing, Black Lives Matter related protests sharply peaked in number at the end of May, declining to dozens per week by September, and are characterized as "an overwhelmingly peaceful movement" with more than 93% of protests involving no incidents of violence nor destructive activity.[21][22] The protests that took place in 140 American cities this spring were mostly peaceful, but the arson, vandalism and looting that did occur will result in at least $1 billion to $2 billion of paid insurance claims. The unrest this year (from May 26 to June 8) will cost the insurance industry far more than any prior incidents of social unrest.[51]

According to Amnesty International's October 2020 report Losing the Peace: U.S. Police Failures to Protect Protesters from Violence, law enforcement agencies across the United States failed to protect protesters from violent armed groups. The incidents documented by Amnesty International show over a dozen protests and counter-protests erupted in violence with police either mostly, or entirely, absent from the scene.[52][53] Amnesty International USA, jointly with the Center for Civilians in Conflict, Human Rights Watch, Physicians for Human Rights, and Human Rights First, sent a letter to governors of U.S. states condemning abuses by law enforcement agencies and calling on governors to ensure the constitutional right to assemble peacefully.[54][55]

Killing of Breonna Taylor

Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old emergency medical technician, was fatally shot by Louisville Metro Police Department (LMPD) officers Jonathan Mattingly, Brett Hankison, and Myles Cosgrove on March 13, 2020. Three plainclothes LMPD officers entered her apartment in Louisville, Kentucky, executing a search warrant. Gunfire was exchanged between Taylor's boyfriend Kenneth Walker and the officers. Walker said that he believed that the officers were intruders. The LMPD officers fired over twenty shots. Taylor was shot eight times[56] and LMPD Sergeant Jonathan Mattingly was injured by gunfire.[57] Another police officer and an LMPD lieutenant were on the scene when the warrant was executed.[58]

The primary targets of the LMPD investigation were Jamarcus Glover and Adrian Walker, who were suspected of selling controlled substances from a drug house more than 10 miles away.[59][60] According to a Taylor family attorney, Glover had dated Taylor two years before and continued to have a "passive friendship".[60] The search warrant included Taylor's residence because it was suspected that Glover received packages containing drugs at Taylor's apartment and because a car registered to Taylor had been seen parked on several occasions in front of Glover's house.[60][61][62]

Kenneth Walker, who was licensed to carry a firearm, fired first, injuring a law enforcement officer, whereupon police returned fire into the apartment with more than 20 rounds. A wrongful death lawsuit filed against the police by the Taylor family's attorney alleges that the officers, who entered Taylor's home "without knocking and without announcing themselves as police officers", opened fire "with a total disregard for the value of human life;" however, according to the police account, the officers did knock and announce themselves before forcing entry.[63][64]

As the shooting occurred during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, at the beginning of an escalating nationwide wave of quarantines and lockdowns, the shooting initially did not receive widespread coverage or attention.[65] Taylor's death became one of the most discussed and protested events of the broader movement.

Killing of George Floyd

According to a police statement, on May 25, 2020, at 8:08 p.m. CDT,[66] Minneapolis Police Department (MPD) officers responded to a 9-1-1 call regarding a "forgery in progress" on Chicago Avenue South in Powderhorn, Minneapolis. MPD Officers Thomas K. Lane and J. Alexander Kueng arrived with their body cameras turned on. A store employee told officers that the man was in a nearby car. Officers approached the car and ordered George Floyd, a 46-year-old African American man, who according to police "appeared to be under the influence", to exit the vehicle, at which point he "physically resisted". According to the MPD, officers "were able to get the suspect into handcuffs, and noted he appeared to be suffering medical distress. Officers called for an ambulance." Once Floyd was handcuffed, he and Officer Lane walked to the sidewalk. Floyd sat on the ground at Officer Lane's direction. In a short conversation, the officer asked Floyd for his name and identification, explaining that he was being arrested for passing counterfeit currency, and asked if he was "on anything". According to the report officers Kueng and Lane attempted to help Floyd to their squad car, but at 8:14 p.m., Floyd stiffened up and fell to the ground. Soon, MPD Officers Derek Chauvin and Tou Thao arrived in a separate squad car. The officers made several more failed attempts to get Floyd into the squad car.[67]

Floyd, who was still handcuffed, went to the ground face down. Officer Kueng held Floyd's back and Lane held his legs. Chauvin placed his left knee in the area of Floyd's head and neck. A Facebook Live livestream recorded by a bystander showed Officer Derek Chauvin kneeling on Floyd's neck.[68][69] Floyd repeatedly tells Chauvin "Please" and "I can't breathe", while a bystander is heard telling the police officer, "You got him down. Let him breathe."[70] After some time, a bystander points out that Floyd was bleeding from his nose while another bystander tells the police that Floyd is "not even resisting arrest right now", to which the police tell the bystanders that Floyd was "talking, he's fine". A bystander replies saying Floyd "ain't fine". A bystander then protests that the police were preventing Floyd from breathing, urging them to "get him off the ground ... You could have put him in the car by now. He's not resisting arrest or nothing."[69] Floyd then goes silent and motionless. Chauvin does not remove his knee until an ambulance arrives. Emergency medical services put Floyd on a stretcher. Not only had Chauvin knelt on Floyd's neck for about seven minutes (including four minutes after Floyd stopped moving) but another video showed an additional two officers had also knelt on Floyd while another officer watched.[71][72]

Although the police report stated that medical services were requested prior to the time Floyd was placed in handcuffs,[73] according to the Minneapolis Star Tribune, Emergency Medical Services arrived at the scene six minutes after getting the call.[74] Medics were unable to detect a pulse, and Floyd was pronounced dead at the hospital.[75] An autopsy of Floyd was conducted on May 26, and the next day, the preliminary report by the Hennepin County Medical Examiner's Office was published, which found "no physical findings that support a diagnosis of traumatic asphyxia or strangulation". Floyd's underlying health conditions included coronary artery disease and hypertensive heart disease. The initial report said that "[t]he combined effects of Mr. Floyd being restrained by the police, his underlying health conditions and any potential intoxicants in his system likely contributed to his death."[76] The medical examiner further said that Floyd was "high on fentanyl and had recently used methamphetamine at the time of his death".[77]

On June 1, a private autopsy which was commissioned by the family of Floyd ruled that Floyd's death was a homicide and it also found that Floyd had died due to asphyxiation which resulted from sustained pressure, which conflicted with the original autopsy report which was completed earlier that week.[78] Shortly after, the official post-mortem declared Floyd's death a homicide.[79] Video footage of Officer Derek Chauvin applying 8 minutes 15 seconds of sustained pressure to Floyd's neck generated global attention and raised questions about the use of force by law enforcement.[80]

On May 26, Chauvin and the other three officers were fired.[81] He was charged with third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter;[82] the former charge was later changed to second-degree murder.[83]

Major protests

Ahmaud Arbery protests, May 8, 2020

On February 23, Ahmaud Arbery was shot and killed in Brunswick, Georgia. Protests ensued in early May after a video surfaced that captured the shooting.[84]

NFAC protests, May 12, 2020

Armed members of the Not Fucking Around Coalition (NFAC) have demonstrated in separate protests across the US, making their first appearance on May 12.[85] On July 4, 100 to 200 NFAC members marched through Stone Mountain Park near Atlanta, Georgia, calling for the removal of the Confederate monument.[86] On July 25, more than 300 members were gathered in Louisville, Kentucky, to protest the lack of action against the officers responsible for the March shooting of Breonna Taylor.[87] On October 3, over 400 members of the NFAC along with over 200 other armed protesters marched in downtown Lafayette, Louisiana.[88]

Breonna Taylor protests, May 26, 2020; jury verdict protests, September 23, 2020

On March 13, Breonna Taylor was shot and killed. Demonstrations over her death began on May 26, 2020, and lasted into August.[90] One person was shot and killed during the protests.[91]

Protest erupted again on September 23, the night after the grand jury verdict was announced, protesters gathered in the Jefferson Square Park area of Louisville, as well as many other cities in the United States, including Los Angeles, Dallas, Minneapolis, New York, Chicago, Seattle.[92] In Louisville, two LMPD officers were shot during the protest and one suspect was kept in custody.[93][94]

George Floyd protests, May 26, 2020

The major catalyst of the unrest was the killing of George Floyd on May 25. Though it was not the first controversial killing of a black person in 2020,[95] it sparked a much wider series of global protests and riots which continued into August 2020.[96][97] As of June 8, there were at least 19 deaths related to the protests.[98] The George Floyd protests are generally regarded as marking the start of the 2020 United States unrest.

In Minneapolis–Saint Paul alone, the immediate aftermath of the killing of George Floyd was second-most destructive period of local unrest in United States history, after the 1992 Los Angeles riots.[99][100][101] Over a three night period, the cities experienced two deaths,[102][103] 617 arrests,[16][101] and upwards of $500 million in property damage to 1,500 locations, including 150 properties that were set on fire.[104]

Sean Monterrosa protests, June 5, 2020 – October 2, 2020

On June 5, protests broke out regarding the June 2 killing of Sean Monterrosa, calling for racial justice.[105][106] These protests continued sporadically but prominently all the way into at least October, resulting in some arrests.[107][108][109][110]

Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone, June 8, 2020

Established on June 8 in Seattle, CHAZ/CHOP was a self-declared autonomous zone established in defiance of the killing of George Floyd after police abandoned the East Precinct building. Groups like the Puget Sound John Brown Gun Club provided security while the protesters themselves provided either resources or assisted the PSJBGC in security. Multiple people were killed in altercations with security[111][112] and on July 1 the autonomous zone/occupied protest was officially cleared by the Seattle Police Department.

Rayshard Brooks protests, June 12, 2020

Further unrest occurred as a result of the killing of Rayshard Brooks on June 12, largely in Atlanta, where he was killed.[113] An 8-year-old girl was shot and killed during the protests.[114]

Andrés Guardado protests, June 18, 2020

Local protests emerged in response to the killing of Guardado on June 18 and involved protesters and media reporters being tear gassed and shot by rubber bullets at the sheriff's station in Compton.[115][116] The incident was widely reported as the second police killing involving the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department deputies within two days of one another, the other being Terron Jammal Boone, who was identified as the half-brother of 24-year-old Robert Fuller.[117][118][119]

Colorado Springs protest, August 4, 2020

In Colorado Springs, a mixture of armed and unarmed left-wing protesters gathered to mark the one year anniversary of the shooting of De'Von Bailey, protesting in the neighborhood of the officer who shot and killed him. After threats of an armed counterprotest, protesters showed up armed. The protest was largely peaceful, except for multiple cases of heated shouting matches between protesters and residents.[120] Later, on September 11, three people who attended the protest were arrested for various charges in a series of raids.[121]

Stone Mountain incident, August 15, 2020

In Stone Mountain, armed Neo-Confederate demonstrators affiliated with the Three Percenters arrived to allegedly protect the Confederate monument, with their operation dubbed "Defend Stone Mountain". They were met with a larger group of armed left-wing counter-protesters, who began pushing them out of the town before the DeKalb County Police Department dispersed both parties.[122] Several minor injuries were reported.

Portland "Back the Blue" Rally, August 22, 2020

The Downtown Portland "Back the Blue" Rally, organized by members of the Proud Boys and QAnon Movement, sparked violence between right-wing protesters and left-wing counter-protesters. Within an hour of meeting, both sides began pushing, punching, paint-balling, and macing each other. There was one incident in which a right-wing Proud Boys protester pointed a gun at left-wing protesters, with no shots fired.[123][124]

Kenosha unrest and shooting, August 23 and 25, 2020; 2020 American athlete strikes

The shooting of Jacob Blake on August 23 sparked protests in a number of American cities, mostly within Kenosha.[125] Two protesters were shot and killed in an incident during the protests.[126] Nationally, athletes from the NHL, NBA, WNBA, MLB, and MLS began going on strike in response to the police shooting of Jacob Blake.[127] On October 14, prosecutors announced that Kyle Rittenhouse, who was charged with killing the two protesters, would not face gun charges in Illinois.[128]

Minneapolis false rumors riot, August 26, 2020

A riot occurred in downtown Minneapolis in reaction to false rumors about the suicide of Eddie Sole Jr., a 38-year-old African American man; demonstrators believed he had been shot by police officers.[129] Surveillance video showed that Sole Jr. shot himself in the head during a manhunt for a homicide suspect in which he was the person of interest.[130] Controversially, the police released the CCTV camera footage of the suicide in attempts to stop the unrest.[131] Overnight vandalism and looting of stores from August 26 to 27 reached a total of 76 property locations in Minneapolis–Saint Paul, including four businesses that were set on fire.[132] State and local officials arrested a total of 132 people during the unrest.[133]

Portland Trump Caravan, August 29, 2020

On August 29, a large group of pro-Trump counterprotesters, arrived in downtown Portland by a vehicle convoy. They were met with opposition from the protesters, resulting in multiple instances of physical clashes.[134] 1 counterprotester was shot and killed in an incident during the protest.[135]

Dijon Kizzee protests, August 31, 2020

Dijon Kizzee, an armed cyclist, was shot and killed in the unincorporated Los Angeles neighborhood of Westmont on Aug 31 by deputies of the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department. For days, protesters gathered outside the heavily guarded South Los Angeles sheriff's station in tense but peaceful demonstrations. By September 6, those demonstrations escalated to clashes, with deputies firing projectiles and tear gas at the crowds and arresting 35 people over four nights of unrest.[136][137]

Daniel Prude protests, September 2, 2020

On March 22, Daniel Prude was killed by Rochester, New York police officers in what was found by the county medical examiner to be a homicide caused through "complications of asphyxia in the setting of physical restraint".[138][139] On September 2, the release of a police body camera video and written reports surrounding his death provoked protests in Rochester.

Deon Kay protests, September 2, 2020

On September 2, Deon Kay, an 18-year-old man, was shot and killed by a police officer in Washington, D.C. Later that day, protesters started gathering outside of the Seventh District Metropolitan Police Department building.[140]

Ricardo Munoz protests, September 13, 2020

On September 13, Protests erupted in Lancaster, Pennsylvania after a police officer shot and killed Ricardo Munoz who allegedly ran at them with a knife. Police later deployed tear gas on a crowd of protesters, saying demonstrators had damaged buildings and government vehicles and thrown bottles.[141]

Deja Stallings protests, October 1, 2020

On September 30, Police arrested 25-year-old Deja Stallings at gas station and convenience store in Kansas City, Missouri in relation to an alleged 15–20 individuals fighting on the business's property. Video footage showed an officer kneeling on the back of Stallings, who is nine months pregnant. In response to the video, demonstrators began protesting outside city hall demanding the resignation of Kansas City Police Department Chief Richard Smith and for the city to redirect 50% of the police department's budget to social services.[142]

Jonathan Price protests, October 5, 2020

On October 5, 31-year old Jonathan Price was killed by a police officer in Wolfe City, Texas after allegedly trying to break off a fight.[143][144] Protests broke out in major cities to which New York City and Los Angeles faced property damage after night of vandalism.[145][146] Shaun David Lucas, a police officer who shot Price, was arrested and charged with murder.[147]

Alvin Cole protests, October 7, 2020

On the afternoon of October 7, the district attorney in Milwaukee County decided to not press charges in relation to the fatal shooting of Alvin Cole, 17 in Wauwatosa, Wisconsin back in February.[148] Protests subsequently occurred since October 7, leading to the arrest of 24 protesters on October 8[149] and 28 protesters on October 9.[150]

Marcellis Stinnette protests, October 22, 2020

On October 22, 19-year old Marcellis Stinnette was shot and killed by an officer in Waukegan, Illinois. His girlfriend, 20-year old Tafarra Williams was also wounded, but is expected to survive.[151] Protests occurred in Waukegan on October 22. The family of Jacob Blake, who was shot 16 miles north of Waukegan in Kenosha, Wisconsin, were also in attendance.[152]

Walter Wallace Jr. protests, October 26, 2020

On October 26 Walter Wallace Jr. was killed by Philadelphia police officers while holding a knife and ignoring orders to drop it. A march for Wallace occurred in West Philadelphia, while other areas of the city reported looting and vandalism.[153] Police also said 30 officers were injured, many struck by bricks and other debris and that 91 protesters were arrested.[154]

Kevin Peterson Jr. protests, October 30, 2020

On October 29, Kevin Peterson Jr. was shot and killed by three Clark County sheriff's deputies in Hazel Dell, Washington, near Vancouver.[155] Hundreds gathered in Hazel Dell for a vigil the following evening with protesters carrying signs saying “Honk for Black lives. White silence is violence” and “Scream his name,” and confronting right-wing counter-protesters. That night, hundreds of protesters marched through Downtown Vancouver, resulting in property damage and a confrontation with federal agents. At least one person was arrested after the protest was declared an unlawful assembly and a dispersal order was issued by police.[156]

Protests against LA Mayor Eric Garcetti, November 23, 2020

On November 23, protesters gathered outside Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti's home due to his refusal to further defund the LAPD. Protests increased when news was released regarding president-elect Joe Biden's consideration of adding Garcetti to his cabinet.[157]

Red House eviction defense protest, December 8, 2020

On December 8, protesters in Portland gathered to blockade parts of the Humboldt Neighborhood in order to protect a family who had been evicted after living in said house for 65 years. Protesters blockaded the area similar to the Capitol Hill Occupied Protest.[158]

Casey Goodson protests, December 11, 2020

On December 4, Casey Goodson was killed by police in Columbus, Ohio, in front of his house. Goodson was killed by a member of a fugitive task force, but Columbus Police have stated that he was not the man the task force was looking for. Protests were held on December 11 and December 12.[159]

Bennie Edwards protests, December 11, 2020

On December 11, Bennie Edwards, a schizophrenic homeless man, was killed by Oklahoma City police while wielding a knife. Demonstrations were held later that evening.[160]

Andre Hill protests, December 24, 2020

On December 22, Andre Hill (also identified as Andre' Hill) was killed by a Columbus Police officer as he left a house where he was a guest. On Christmas Eve, protests were held in response to the shooting. The shooting was the second police killing in Columbus in the month, following the shooting of Casey Goodson.[161]

Dolal Idd protests, December 30, 2020

On December 30, Dolal Idd, a 23-year old Somali-American man, was shot and killed by Minneapolis police officers during a felony traffic stop.[162] Idd's death was the first killing by a Minneapolis police since George Floyd on May 25.[163]

Rochester protests, February 1, 2021

About 200 protesters marched in Rochester, New York, on February 1 after a nine-year-old girl was handcuffed and pepper-sprayed by police.[164] Community outrage swelled following release of footage the previous day showing officers restraining and scolding a girl, who was screaming for her father. At one point, an officer is heard telling her to "stop acting like a child," to which she cried, "I am a child."[164] Protesters ripped away barricades protecting a Rochester police precinct as hundreds took to the streets in outrage.[165]

Themes and demands

"Defund the police"

Unlike recent racial protests in the United States before it, the 2020 protests frequently included the slogan "defund the police", representing a call for divestment in policing.[166] The degree of divestment advocated varied, with some protesters calling for elimination of police departments, and others for reduced budgets. Supporters of partial or complete defunding of the police argued that budgets should be directed instead towards community-driven police alternatives, investment in mental health and substance abuse treatment services, job-training programs, or other forms of investment into black urban communities. In June 2020, New York City mayor Bill De Blasio responded to calls for divestment by cutting $1B of the New York City Police Department (NYPD)'s $6B budget and directing it instead to city youth groups and social services, a reduction of 17%.[167] The cut mostly involved shifting some responsibilities to other city agencies, with the size of the force barely changing.[168]

The city council in Minneapolis voted in June to "end policing as we know it" and replace it with a "holistic" approach to public safety, but by September 2020, the pledge collapsed without implementation.[169][170] An increasing number of community groups had opposed the pledge, a poll from the Minneapolis Star-Tribune showed that a plurality of residents, including 50% of black people, opposed decreasing the size of the police force, and city councilors cited alarm from business owners and residents in more affluent areas of their wards who feared for their safety, as beliefs anticipating an immediate end to the police department proliferated.[170] Incremental reforms of a type that the city's progressive politicians had denounced were pursued in lieu of the pledge.[170] The Black Visions Collective, an activist group seeking police abolition, called past reforms "weak" and stated, "It is the nature of white supremacy, capitalism, patriarchy or any of these other systems of oppression to want to do what is necessary to save themselves" and "To adapt. To mutate. To move. To slow progress."[170]

Nationwide, defunding the police has not received broad support from congressional Democrats,[170] former Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, or 2020 Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden; both Sanders and Biden support reform instead.[171][172] Defunding the police was heavily criticized by President Donald Trump.[170]

Monument removals

Protesters have called for the removal of statues commemorating historical figures who are perceived as racist by modern standards. Often those depicted in the statues were responsible for human rights violations.[173] A number were either removed by authorities, or vandalized and toppled by protesters.[174] In particular, the statues of Confederate war veterans and politicians as well as of Christopher Columbus. Statues of United States presidents, including the Emancipation Memorial featuring Abraham Lincoln, have also been vandalized and attacked by protesters.[175]

Related racial unrest outside the United States

Writing for Foreign Affairs, professor Brenda Gayle Plummer noted that "The particulars of Floyd's murder, taking place against the backdrop of the pandemic, may well have been the dam-break moment for the global protest movement. But they are only part of the story. International solidarity with the African American civil rights struggle comes not from some kind of projection or spontaneous sentiment; it was seeded by centuries of black activism abroad and foreign concern about human rights violations in the United States."[176]

Netherlands

Related racial unrest in the Netherlands included widespread participation in George Floyd protests. The unrest has led to a change in public opinion on Zwarte Piet, a character used in Dutch Sinterklaas celebrations who has been historically portrayed in blackface. Leaving the appearance of Zwarte Piet unaltered has traditionally been supported by the public but opposed by anti-racism campaigners, but a June 2020 survey saw a drop in support for leaving the character's appearance unaltered: 47 per cent of those surveyed supported the traditional appearance, compared to 71 per cent in a similar survey held in November 2019.[177] Prime minister Mark Rutte stated in a parliamentary debate on June 5, 2020 that he had changed his opinion on the issue and now has more understanding for people who consider the character's appearance to be racist.[178]

United Kingdom

The 2020–2021 United States racial unrest has triggered protests, political gestures and policy changes in the United Kingdom, both in solidarity with the United States and in comparable protest against racism in the United Kingdom.[179] The debate over statues of certain historical figures has been a significant feature of the unrest in Britain, following the unauthorized removal of the statue of Edward Colston in Bristol on June 11 during a protest in the city.[180][181][182][183] The Culture Secretary Oliver Dowden wrote a three-page letter to MPs, peers and councillors arguing against the removal of statues.[184] Prime Minister Boris Johnson condemned protesters who defaced the statue of Winston Churchill in Parliament Square in London,[185][186] and several statues were subsequently covered up as a precaution.[187]

Social impact

In late May to June 2020, the high-profile killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery led to a racial reckoning that greatly increased sentiment regarding systemic racism in the United States, with changes occurring in public opinion, government, industry, and sports.[38][39][188] This racial reckoning aimed at confronting a legacy[38][39] of systemic inequality and racial injustice stemming from overt discrimination and unconscious bias in the societal treatment of black Americans, who have experienced disproportionately negative outcomes in the form of racial inequality such as in education, health care, housing, imprisonment, voting rights and wages.[36][38][189][190] While most black Americans acutely felt these issues, many white Americans were insulated.[36]

Previously, there had been protests and riots over killings of black Americans by law enforcement. The 2014 killing of Michael Brown, the 2014 killing of Eric Garner, the 2015 Charleston church shooting, and the 2017 Charlottesville rally received headlines yet did not lead to systemic change[35] or as wide a level of support.[37] However, the videos of Floyd's death and police violence at protests resonated with many white Americans.[191] White people have attended the George Floyd protests and continuing related protests in greater numbers than they had prior protests of killings of black Americans by law enforcement.[36]

Public opinion

By mid-June, after weeks of protests during the global COVID-19 pandemic and recession, American national culture and attitude towards racial injustice began to shift, including the Senate Armed Services Committee's approval of process to rename military facilities named for Confederate generals.[35] American public opinion of racism and discrimination shifted in the wake of these protests. Polling of white Americans showed an increased belief in having received advantages due to their race and increased belief that black Americans received disproportionate force in policing.[38] Public opinion in support of the Black Lives Matter movement greatly increased,[192][193] with a surge of "am I racist" searches[194] and a greater approval for removing Confederate statues and memorials.[195] However, support for the Black Lives Matter movement declined by August and September 2020.[196][197][198]

The increased approval of racial justice reform may have been influenced by opposition towards President Donald Trump's support for police, greater understanding of disparate pandemic effects by race,[35] and a weakened sense of security following the COVID-19 pandemic's social distancing and an economic fallout with the COVID-19 recession.[191] Others had grown accustomed to protest under Trump or were responding to his racial views, agitation and "demagoguery" or handling of the pandemic.[37] Some white Americans reported feeling more social permission from other white people to support Black Lives Matter whereas it would have felt conspicuous prior.[37]

Public debate

Faced with civil unrest, politicians fulfilled promises to remove Confederate symbols.[199] Activism spread to other Confederate symbols, especially the modern display of the Confederate battle flag. NASCAR banned its display, and organizations including Walmart and the NCAA announced that they would no longer fly the Mississippi flag, the last state flag to include the symbol. The state also voted to retire the flag.[200] The removal of symbols caused national debate over the appropriateness of statues of figures tied to racial injustice.[201]

Public backlash widened to other institutional symbols, including place names, namesakes, brands and resignations. Examples include Rhode Island removing "Providence Plantations" from the state's formal name,[202] plans to remove the Native American below a sword from the Massachusetts state flag and seal,[203] Princeton University renaming its Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, [199][202] household products such as Aunt Jemima syrup, Uncle Ben's rice and Cream of Wheat pledging to review racial stereotypes in their marketing,[204] music groups including the Dixie Chicks and Lady Antebellum changing their names to remove references to the Southern United States,[205] and the Washington Redskins pledging to change its name following pressure from business sponsors and a 12-year advocacy campaign.[206][39] Some firms in the music industry also phased out the term "urban music"[207] and a social media debate considered whether the United States should change its national anthem based on a verse that some historians interpret as supporting violence against slaves.[208] Companies that had donated to Black Lives Matter causes without addressing internal diversity issues were criticized on social media. Leaders in the media and entertainment industries were also criticized over their handling of racial issues, as were other celebrities and actors.[209] Debates continued across corporate leadership, media organizations and other cultural institutions. Researchers also went on strike in support of the movement.[192]

Public conversations on race and power extended to other cultural practices. One debate addressed racial vocabulary. Hundreds of news organizations modified their style guides to capitalize "Black" as a proper noun in recognition of the term's shared political identity and experiences.[210][211] Merriam-Webster modified its definition of racism.[192] GitHub reconsidered and replaced words and phrases with similarities to discriminatory terms such as "master bedroom" and "whitelist"/"blacklist", which also encompassed "master/slave" distinctions in technology and also situations which refer to the master as the opposite of a copy.[212] Real estate and technology organizations announced they would use more inclusive alternatives.[213] Journalists at major American newspapers contested their own coverage of the events.[214][215][216] In the music industry, the BMG Rights Management announced it would reevaluate its record deals for race-based compensation disparities.[217] Major record labels began searches for diversity officers and the Black Music Action Coalition formed to address industry racial inequities.[207] The major sports channel ESPN began to air political commentary, reversing a longstanding mandate to separate sports from politics.[218] College athletes led boycotts[219] and a wildcat strike during the NBA playoff led to a work stoppage from other American professional athletes following the August shooting of Jacob Blake.[220][221][222]

Consumer behavior

Anti-racist self-education became a trend throughout June 2020 in the United States and black anti-racist writers found new audiences. During the Floyd protests, black-owned bookstores saw an influx of interest, especially for books on social justice topics. In the span of two weeks from early to late June, books about race went from composing none to two-thirds of The New York Times Best Seller list. Amazon sales saw a similar pattern. In comparison, no such surge happened after prior prominent Black Lives Matter demonstrations. Popular black authors included Ibram X. Kendi (How to Be an Antiracist, Stamped from the Beginning), Ijeoma Oluo (So You Want to Talk About Race) and Layla Saad (Me and White Supremacy). Bestsellers also include black biographies and memoirs (Becoming, Born a Crime, Between the World and Me, Just Mercy), anti-racist books by white authors (White Fragility, The Color of Law) and older books (The New Jim Crow, The Fire Next Time). Online library checkouts of anti-racist literature increased tenfold by mid-June. Some municipal libraries saw waitlists in the thousands per title. Amazon's tracking of daily e-book readers and audiobook listeners reflected the increased readership, when many of the aforementioned books entered its most-read list.[223]

American consumers sought out black-owned businesses to support. June saw record high Google searches for "Black-owned businesses near me" and smartphone restaurant discovery apps added features for discovering black-owned restaurants. Businesses on social media lists saw significantly increased sales. Black-owned bookstores in particular had difficulty meeting demand.[224][225][226][227] There was also a social media and Facebook boycott on self-education.[228]

Many major American corporations pursued anti-racism and diversity training workshops, particularly companies seeking to be consistent with their Black Lives Matter messaging. Demand for these trainings had grown over time, especially since 2016, interest in diversity training bookings spiked during this period of reckoning. Robin DiAngelo, whose White Fragility topped the Amazon bestsellers list, rose to prominence during this time and was a popular speaker.[229]

Analysis

The recent scrutiny on race relations in the United States brought comparisons to the Weinstein effect in which the Me Too movement put pressure on public figures for legacies of sexual assault, harassment, and systemic sexism.[36][209][230] Similarly, the American public under its racial injustice reckoning pressured American industries to confront legacies of racism.[230] The resulting symbolic divestments targeted white cultural hegemony.[35] NPR wrote that renamed landmarks and similar gestures would not provide economic opportunities or civil rights, but signaled cultural disapproval towards symbols associated with racial injustice, including the history of racism and slavery.[35] The New Yorker compared the dispersed national response to an "American Spring" on par with the Arab Spring and other international revolutionary waves.[36] Global protests also focused on symbols of racial injustice, with The New Yorker also having a part on international solidarity towards police violence.[36]

Firearms

The unrest precipitated an unprecedented number of firearm sales in the United States[231] Background checks for legally purchased firearms reached record highs starting in May,[232] with year-on-year numbers up 80.2%[233][234][235][236] and running through the rest of the summer.[237] This represented the highest monthly number of firearms transfers since the FBI began keeping records in 1998.[238]

In May 2020, firearms retailers surveyed by the National Shooting Sports Foundation estimated that 40% of their sales came from first-time gun buyers, 40% of those first-time gun buyers were women. Gun sales have been up across the country, a rise in first-time gun buyers in liberal-leaning states like California have helped fuel the national uptick in firearms and ammunition purchases.[239][240][241] June 2020 represented the largest month of firearms purchases in United States history, with Illinois purchasing more firearms than any other state.[242]

The last days of May and first week of June 2020, there were more than 90 attempted or successful burglaries of gun stores, according to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (BATF). More than 1,000 guns were stolen in that window of time. On May 31 alone, the BATF reported 29 separate burglaries targeting licensed firearm retailers.[243][244]

Maps

Minneapolis civil unrest, East Lake Street

Minneapolis civil unrest, East Lake Street Saint Paul civil unrest, University Avenue West

Saint Paul civil unrest, University Avenue West Minneapolis civil unrest, Nicollet Avenue

Minneapolis civil unrest, Nicollet Avenue Seattle civil unrest, Capitol Hill

Seattle civil unrest, Capitol Hill Portland civil unrest, downtown

Portland civil unrest, downtown Kenosha civil unrest, downtown

Kenosha civil unrest, downtown Portland Civil Unrest, Humboldt

Portland Civil Unrest, Humboldt

See also

- Killing of Manuel Ellis

- Death of Elijah McClain

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

- Mass racial violence in the United States

- Timeline of notable Black Lives Matter events and demonstrations in the United States

- 2020–2021 United States election protests

- Similar unrest

- Ghetto riots in the United States (1964–1969)

- 1980 Miami riots

- 1992 Los Angeles riots

- 2014 Ferguson unrest

- 2015 Baltimore protests

- 2017 Charlottesville protests (Unite the Right rally)

References

- Owermohle, Sarah (June 1, 2020). "Surgeon general: 'You understand the anger'". Politico. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

-

- VOA News. "Anti-Racism Protests Continue in US | Voice of America - English". voanews.com. Voice of America. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- Bronner, Laura (June 25, 2020). "Why Statistics Don't Capture The Full Extent Of The Systemic Bias In Policing". FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- Cheung, Helier (June 8, 2020). "Why US protests are so powerful this time". BBC News. Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- Sabur, Rozina; Sawer, Patrick; Millward, David (June 7, 2020). "Why are there protests over the death of George Floyd?". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved July 8, 2020.

- Cities Are Losing Police Chiefs and Struggling to Hire New Ones

- Beckett, Lois (October 31, 2020). "At least 25 Americans were killed during protests and political unrest in 2020". The Guardian. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- W.C. Mann. "More than 400 law enforcement officers injured in riots across U.S., 2 dead". cullmantribune.com. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- "Hawaiian shirts, guns and anticipation of war: Who are the 'Boogaloo boys'?". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. June 27, 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- "Vandalism, looting after Floyd's death sparks at least $1 billion in damages:report". The Hill. September 17, 2020. Retrieved October 9, 2020.

- Peterson, Hayley. "A Minneapolis Target store was destroyed by looting. Photos show the flooded remains". Business Insider. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- Press, Tim Sullivan, The Associated Press, Amy Forliti, The Associated (May 30, 2020). "Minnesota governor activates National Guard as Minneapolis braces for more violence". Military Times. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- Reilly, Mark (July 13, 2020). "FEMA rejects Minnesota plea to help rebuild after riots". Minneapolis / St. Paul Business Journal.

- Ruiz, Michael (July 2, 2020). "Minnesota Gov. Walz asks Trump for disaster declaration after George Floyd riots trigger over $500M in damages". Fox News. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- Norwood, Candice (June 9, 2020). "'Optics matter.' National Guard deployments amid unrest have a long and controversial history". PBS NewsHour.

- Warren, Katy; Hadden, Joey (June 4, 2020). "How all 50 states are responding to the George Floyd protests, from imposing curfews to calling in the National Guard". Business Insider. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- Sternlicht, Alexandra. "Over 4,400 Arrests, 62,000 National Guard Troops Deployed: George Floyd Protests By The Numbers". Forbes. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- Olson, Emily (June 27, 2020). "Antifa, Boogaloo boys, white nationalists: Which extremists showed up to the US Black Lives Matter protests?". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- Pham, Scott (June 2, 2020). "Police Arrested More Than 11,000 People At Protests Across The US". BuzzFeed News.

- "Associated Press tally shows at least 9,300 people arrested in protests since killing of George Floyd". Associated Press. June 3, 2020. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- Croft, Jay. "Some Americans mark Fourth of July with protests". CNN. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- Buchanan, Larry; Bui, Quoctrung; Patel, Jugal K. (July 3, 2020). "Black Lives Matter May Be the Largest Movement in U.S. History". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- "Riot declared as Portland protests move to City Hall on 3-month anniversary of George Floyd's death". Oregon Live. August 25, 2020. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- Craig, Tim. "'The United States is in crisis': Report tracks thousands of summer protests, most nonviolent" – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- Kishi, Roudabeh; Jones, Sam (September 3, 2020). Demonstrations & Political Violence in America: New Data for Summer 2020 (Report). Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project. Lay summary – The Guardian (September 5, 2020).

- Chenoweth, Erica; Pressman, Jeremy. "This summer's Black Lives Matter protesters were overwhelmingly peaceful, our research finds". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved October 23, 2020 – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- Udoma, Ebong. "UConn Study: At Least 96% of Black Lives Matter Protests Were Peaceful". www.wshu.org. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- "False 'thug' narratives have long been used to discredit movements". NBC News. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- Kingson, Jennifer A. (September 16, 2020). "Exclusive: $1 billion-plus riot damage is most expensive in insurance history". Axios. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- "Legend Taliferro". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- "Violent Crime in the United States".

- Badger, Emily (July 23, 2020). "How Trump's Use of Federal Forces in Cities Differs From Past Presidents". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- "Troops to deploy in three more US cities as federal forces begin Portland withdrawal". France 24. July 29, 2020. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- "Operation Legend". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- Fandos, Nicholas (June 6, 2020). "Democrats to Propose Broad Bill to Target Police Misconduct and Racial Bias". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- Hawkins, Derek (June 8, 2020). "9 Minneapolis City Council members announce plans to disband police department". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- Journal-Constitution, Chris Joyner-The Atlanta Journal-ConstitutionMarlon A. Walker- The Atlanta. "Protesters clash in Stone Mountain". ajc. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- Elving, Ron (June 13, 2020). "Will This Be The Moment Of Reckoning On Race That Lasts?". NPR.org. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- Cobb, Jelani (June 14, 2020). "An American Spring of Reckoning". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- Demby, Gene (June 16, 2020). "Why Now, White People? : Code Switch". NPR. Archived from the original on July 5, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- Coleburn, Christina (June 29, 2020). "The Ostrich Rears its Head: America's 2020 Racial Reckoning is a Victory and Opportunity". Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review. Archived from the original on September 5, 2020. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- Wallbank, Derek (July 13, 2020). "Washington NFL Team Bows to Pressure, Drops 'Redskins' Name". Bloomberg.com.

- Balz, Dan; Miller, Greg (June 6, 2020). "America convulses amid a week of protests, but can it change?". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- "The Counted: People killed by police in the US". The Guardian.

- Hinton, Elizabeth (2016). From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America. Harvard University Press. pp. 68–72. ISBN 9780674737235.

- "Los Angeles riots: Remember the 63 people who died". April 26, 2012.

- Luibrand, Shannon (August 7, 2015). "Black Lives Matter: How the events in Ferguson sparked a movement in America". CBS News. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- Ellis, Ralph; Kirkos, Bill (June 16, 2017). "Officer who shot Philando Castile found not guilty". CNN. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- Miller, Trace (June 1, 2020). "'This Rage That You Hear Is Real': On the Ground at the Dallas Protests". D Magazine.

- Haines, Errin (May 11, 2020). "Family seeks answers in fatal police shooting of Louisville woman in her apartment". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 24, 2020.

- Tatum, Brandon (August 30, 2020). "UPDATED: Shocking Report Leaked in Breonna Taylor Death Investigation Shows How Involved She Really Was". The Tatum Report.

- WHAS11 News (August 30, 2020). "The warrant was not served as a no-knock warrant Kentucky AG says". WHAS11 NEWS.

- "Fatal Force: Police shootings database". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- Kingson, Jennifer A. (September 16, 2020). "Exclusive: $1 billion-plus riot damage is most expensive in insurance history". Axios.

- Losing the Peace: U.S. Police Failures to Protect Protesters from Violence (PDF) (Report). Amnesty International. October 2020. AMR 51/3238/2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 26, 2020. Lay summary.

- "Police in U.S. failing to protect protesters from violence, as volatile elections near". Today News Africa. October 24, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- "Protect Peaceful Assemblies; Limit Use of Force" (Press release). Amnesty International. October 21, 2020. Archived from the original on November 6, 2020.

- i_beebe (November 2, 2020). "Civil rights activists question NYPD preparation for protests". CSNY. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- Bailey, Tessa Duvall, Darcy Costello and Phillip M. (May 14, 2020). "Senator Kamala Harris demands federal investigation of police shooting of Breonna Taylor in Kentucky". USA Today. Archived from the original on May 13, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- Wise, John (March 13, 2020). "Officers, suspect involved in deadly confrontation identified". Archived from the original on May 30, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

Sgt. Jon Mattingly, who has been with LMPD since 2000, also was struck by gunfire. He's expected to survive.

- Darcy Costello & Tessa Duvall, Who are the 3 Louisville officers involved in the Breonna Taylor shooting? What we know, Louisville Courier Journal (May 16, 2020; updated June 20, 2020).

- Duvall, Tessa; Costello, Darcy (May 12, 2020). "Senator Kamala Harris demands federal investigation of police shooting of Breonna Taylor in Kentucky". Louisville Courier Journal.

- Duvall, Tessa (June 16, 2020). "FACT CHECK: 7 widely shared inaccuracies in the fatal police shooting of Breonna Taylor". The Courier-Journal. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Burke, Minyvonne (May 13, 2020). "Breonna Taylor police shooting: What we know about the Kentucky woman's death". NBC News. Archived from the original on May 30, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

Her address was listed on the search warrant based on police's belief that Glover had used her apartment to receive mail, keep drugs or stash money. The warrant also stated that a car registered to Taylor had been seen parked on several occasions in front of a "drug house" known to Glover.

- "The Killing of Breonna Taylor, Part 2". The New York Times. September 10, 2020. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- Burke, Minyvonne (May 13, 2020). "Woman shot and killed by Kentucky police who entered wrong home, family says". NBC News. Archived from the original on May 14, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- Brito, Christopher (May 15, 2020). "Family sues after 26-year-old EMT is shot and killed by police in her own home". CBS News. Archived from the original on May 15, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- Wood, Josh (May 14, 2020). "Breonna Taylor shooting: hunt for answers in case of black woman killed by police". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 14, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- Ries, Brian (June 2, 2020). "8 notable details in the criminal complaint against ex-Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin". cnn.com. Cable News Network. Archived from the original on May 29, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Michelle M Frascone; Amy Sweasy (May 29, 2020). "State of Minnesota v. Derek Michael Chauvin" (PDF).

- Hauser, Christine (May 26, 2020). "F.B.I. to Investigate Arrest of Black Man Who Died After Being Pinned by Officer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2020. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- Dakss, Brian (May 26, 2020). "Video shows Minneapolis cop with knee on neck of motionless, moaning man who later died". CBS News. Archived from the original on May 26, 2020. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- Nawaz, Amna (May 26, 2020). "What we know about George Floyd's death in Minneapolis police custody". PBS Newshour. Archived from the original on May 27, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Montgomery, Blake (May 27, 2020). "Black Lives Matter Protests Over George Floyd's Death Spread Across the Country". The Daily Beast. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

Floyd, 46, died after a white Minneapolis police officer, Derek Chauvin, kneeled on his neck for at least seven minutes while handcuffing him.

- Murphy, Paul P. (May 29, 2020). "New video appears to show three police officers kneeling on George Floyd". CNN. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- "Investigative Update on Critical Incident". Minneapolis police. Archived from the original on May 26, 2020. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- Sawyer, Liz. "George Floyd showed no signs of life from time EMS arrived, fire department report says". Minneapolis Tribune. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- Steinbuch, Yaron (May 28, 2020). "First responders tried to save George Floyd's life for almost an hour". New York Post. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Soellner, Mica (May 29, 2020). "Medical examiner concludes George Floyd didn't die of asphyxia". Washington Examiner. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Wilson, Jim (June 2, 2020). "Competing autopsies say Floyd's death was a homicide, but differ on causes". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 2, 2020. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

The medical examiner also cited significant contributing conditions, saying that Mr. Floyd suffered from heart disease, and he was also high on fentanyl and had used methamphetamine at the time of his death.

- Vera, Amir (June 1, 2020). "Independent autopsy finds George Floyd's death a homicide due to 'asphyxiation from sustained pressure'". CNN. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- "Floyd death homicide, official post-mortem says". BBC News. June 1, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Hill, Evan; Tiefenthäler, Ainara; Triebert, Christiaan; Jordan, Drew; Willis, Haley; Stein, Robin (May 31, 2020). "How George Floyd Was Killed in Police Custody". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- Andrew, Scottie (June 1, 2020). "Derek Chauvin: What we know about the former officer charged in George Floyd's death". CNN.

- "Fired Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, who knelt on George Floyd's neck, arrested". The Boston Globe. Associated Press. May 29, 2020. Archived from the original on May 30, 2020. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Madani, Doha (June 3, 2020). "3 more Minneapolis officers charged in George Floyd death, Derek Chauvin charges elevated". NBC News. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- Fausset, Richard (September 10, 2020). "What We Know About the Shooting Death of Ahmaud Arbery". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- Davis, Zuri (May 29, 2020). "Black Civilians Arm Themselves To Protest Racial Violence and Protect Black-Owned Businesses". Reason.com. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- "'I'm in your house' – Armed group condemns systemic and overt racism, marches to Stone Mountain". 11Alive.com. July 4, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- Kenning, Chris, et al. "Opposing armed militias converge in Louisville, escalating tensions but avoiding violence." Courier Journal. July 25, 2020. Retrieved August 29, 2020.

- "NFAC march: Protest in Lafayette ends as organizers proclaim 'another successful demonstration'". The Daily Advertiser (Lafayette, Louisiana). Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- Demonstrations & Political Violence In America: New Data For Summer 2020 // Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project

- Wolfson, Andrew. "Lawyer for protest group seeks to block enforcement of new Louisville police policy". The Courier-Journal. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- "Authorities identify suspect in fatal shooting at Jefferson Square Park". WDRB. June 29, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- Callimachi, Rukmini; Bogel-Burroughs, Nicholas; Eligon, John (September 24, 2020). "Breonna Taylor Live Updates: 2 Officers Shot in Louisville Protests". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- Yancey-Bragg, N'dea. "Breonna Taylor case: Two police officers shot during protest after officials announce charges; FBI SWAT team at scene". USA TODAY. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- Krauth, Bailey Loosemore, Emma Austin, Hayes Gardner, Ben Tobin, Sarah Ladd, Mandy McLaren and Olivia. "LIVE UPDATES: Protesters downtown as 9 p.m. curfew starts, report of officer shot". The Courier-Journal. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- Mahdawi, Arwa (June 6, 2020). "We must keep fighting for justice for Breonna Taylor. We must keep saying her name | Arwa Mahdawi". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- "George Floyd protests: police declare a riot outside precinct in Portland". the Guardian. Associated Press. August 22, 2020. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- "2020 is not 1968: To understand today's protests, you must look further back". History & Culture. June 11, 2020. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- McEvoy, Jemima. "14 Days Of Protests, 19 Dead". Forbes. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- Penrod, Josh; Sinner, C.J.; Webster, MaryJo (June 19, 2020). "Buildings damaged in Minneapolis, St. Paul after riots". Star Tribune.

- Braxton, Grey (June 16, 2020). "They documented the ’92 L.A. uprising. Here's how the George Floyd movement compares". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved on July 6, 2020.

- Lurie, Julia (July 15, 2020). "Weeks Later, 500 People Still Face Charges for Peacefully Protesting in Minneapolis". Mother Jones. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- Mystery remains weeks after a pawnshop owner fatally shot a man during Minneapolis unrest Star Tribune.

- Jany, Libor (July 20, 2020). "Authorities: Body found in wreckage of S. Minneapolis pawn shop burned during George Floyd unrest". Star Tribune. Retrieved on July 20, 2020.

- "For riot-damaged Twin Cities businesses, rebuilding begins with donations, pressure on government". Star Tribune. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- Bauman, Anna (June 5, 2020). "Hundreds kneel in Mission District to remember Sean Monterrosa, killed by Vallejo police". sfchronicle.com. San Francisco Chroncile. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- "Family of Man Killed By Vallejo Officer: 'They Executed Him'". SFist. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- John, Kevin (June 13, 2020). "Hundreds of people protest death of San Francisco man shot by Vallejo police". abc10.com. ABC10. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- "Oree Originol, Justice for Sean Monterrosa". oreeoriginol.com. July 11, 2020. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- Gase, Thomas (September 27, 2020). "Vallejo gathering held for Sean Monterrosa billboard near police station". timesheraldonline.com. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- Cruz Guevarra, Ericka (October 3, 2020). "Monterrosa Sisters Arrested Protesting Outside Newsom's Home". kqed.com. PBS. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- "Seattle: one teen killed and another injured in shooting in police-free zone".

- "Shooting in Seattle protest zone leaves one dead. Police say 'violent crowd' denied them entry". CNN. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- Staff, WSBTV com News. "Rayshard Brooks shooting: Protesters block traffic on Atlanta highway". WJAX. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- Burns, Asia Simone (July 5, 2020). "Police ID 8-year-old shot, killed; $10,000 reward offered in case; Atlanta mayor: 'Enough is Enough'". ajc.com. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on July 6, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- "A march for a man shot and killed by police ended with protesters being shot by rubber bullets". CNN. June 22, 2020. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- "Tension As Peaceful March Takes Confrontational Turn In Protest Of Fatal Shooting By Deputy". LAist. June 22, 2020. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- "'He Ran Because He Was Scared': LASD Deputies Shoot, Kill Auto Body Shop Security Guard In Gardena". CBS Los Angeles. June 19, 2020. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- Lee, ArLuther (June 19, 2020). "Police shoot, kill 18-year-old Hispanic security guard on patrol at LA auto shop". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- "Police officers shoot and kill Los Angeles security guard: 'He ran because he was scared'". The Guardian. June 19, 2020. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- Boyce, Dan. "Anniversary Of De'Von Bailey Shooting Marked With Tense Protest In Officer's Colorado Springs Neighborhood". Colorado Public Radio.

- Boyce, Dan. "Three Arrested In Connection With August Protest Outside Colorado Springs Police Officer's Home". Colorado Public Radio.

-

- "Protesters clash in Stone Mountain -English". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

-

- "Protesters fight using pepper spray, baseball bats in Portland on Saturday -English". Oregon Public Broadcasting. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- "In photos: Black Lives Matter organization rallies in Kenosha". Kenosha News. Archived from the original on August 27, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- Bredderman, Pilar Melendez,William (August 26, 2020). "17-Year-Old 'Blue Lives Matter' Fanatic Charged With Murder at Kenosha Protest". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on August 26, 2020. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- Gretz, Adam (August 28, 2020). "NHL players speak on decision to postpone playoff games". NBC Sports. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- "Teen accused in fatal protest shootings will not face gun charges in Illinois: prosecutors". pennlive. Associated Press. October 14, 2020. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- "Homicide Suspect Who Shot Self On Nicollet Mall Identified". August 28, 2020. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- Levenson, Michael (August 26, 2020). "Minneapolis Homicide Suspect's Suicide Spurs More Protests, Police Say". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- "When a graphic video can bring both truth and harm". MPR News. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- Sinner, C.J.; Penrod, Josh; Hyatt, Kim (September 3, 2020). "Map of Minneapolis businesses damaged, looted after night of unrest". Star Tribune.

- "132 arrests made during unrest, looting in Minneapolis overnight". KMSP (FOX-9). August 27, 2020.

- The New York Times. "One Person Dead in Portland After Clashes Between Trump Supporters and Protesters". Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- "UNSEALED DOCUMENTS SHED LIGHT ON MOMENTS BEFORE FATAL DOWNTOWN PORTLAND SHOOTING". KGW8. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- Huang, Josie. "In South LA, March For Dijon Kizzee Turns Chaotic Outside Sheriff's Station". LAist.

- Miller, Leila; Tchekmedyian, Alene (September 9, 2020). "Dozens arrested as protesters and deputies clash in Dijon Kizzee demonstrations in L.A." Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- WROC staff (September 2, 2020). "Autopsy report: Daniel Prude death ruled a homicide, died from asphyxia due to 'physical restraint'". Rochester First. Archived from the original on September 2, 2020. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- "What to Know About Daniel Prude's Death". The New York Times: New York Today. September 4, 2020. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- Mitchell, Samantha; Gayle, Anna-Lysa (September 2, 2020). "Protesters gather outside D.C. police department after officers shoot person in SE". WJLA-TV. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- Budryk, Zack (September 14, 2020). "Protest erupts in Lancaster, Pa., after police fatally shoot man carrying knife". The Hill.

- Toropin, Konstantin. "Footage of a Kansas City officer kneeling on the back of a pregnant Black woman sparks ongoing protest". CNN. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- McCullough, Jolie (October 6, 2020). "Texas police officer arrested on suspicion of murder in fatal shooting of Jonathan Price". The Texas Tribune. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- "Who is Jonathan Price?". wfaa.com. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- "NYPD arrests 24 'spoiled brats' during Jonathan Price protest, Commissioner Shea says". New York Post. October 7, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- "Vandalism Occurs During Downtown LA Protests Possibly Spurred By Jonathan Price Killing". October 6, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- "Police Officer Shaun David Lucas Arrested, Charged With Murder In Connection To Jonathan Price Slaying". October 5, 2020. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- "No charges against Wisconsin officer who fatally shot teen". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- Ali, Rasha. "Jay-Z offers to pay fines for those arrested during protests for Alvin Cole, including mom and sisters". USA TODAY. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- Chavez, Nicole. "More arrests in Wisconsin on fourth night of protests over Alvin Cole's death". CNN. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- Karma, Roge (October 24, 2020). "The police shooting of Marcellis Stinnette and Tafara Williams, an unarmed Black couple, explained". Vox. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- "Illinois officer fired after shooting Black couple inside their vehicle". The Guardian. Associated Press. October 24, 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- Chang, David; DeLucia, Matt. "VIDEO: Woman Tries to Restrain Son Moments Before Deadly Police Shooting". WCAU.

- "VIDEO: Mother Tries to Restrain Son Moments Before He Was Shot, Killed by Police". NBC10 Philadelphia. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- Hutchinson, Bill (November 1, 2020). "Protests erupt over fatal shooting of Black man by deputies near Vancouver, Washington". ABC News. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- Flaccus, Gillian (October 31, 2020). "Unrest erupts over police killing of Black man near Portland". WSOC-TV. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- "BLM supporters continue to protest Biden's consideration of LA Mayor Garcetti for cabinet". Fox News. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- "Portland mayor authorizes 'all lawful means' to clear protesters from occupied area on Mississippi Ave". OPB. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- Widman Neese, Alissa; Gordon, Ken (December 13, 2020). "Hundreds join two days of peaceful protests over the shooting of Casey Goodson Jr". The Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- Sweetman, Cassandra (December 11, 2020). "Protest erupts after Oklahoma police shoot, kill homeless man allegedly armed with knife". Fox 8. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- Landers, Kevin (December 24, 2020). "Dozens protest in north Columbus neighborhood where Andre' Hill was fatally shot". 10 WBNS. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- Glass, Doug (December 30, 2020). "Minneapolis police release officer video in fatal shooting". Associated Press.

- Collins, Williams; Williams, Brandt (December 31, 2020). "Police shooting victim ID'd; MPD bodycam footage released". Minnesota Public Radio.

- Walker, Adria R. "Outrage in Rochester: 'RPD look what you did, you just maced a little kid.'". Democrat and Chronicle. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- Brown, Lee (February 2, 2021). "Protesters tear down barricades at Rochester police precinct amid arrest outrage". New York Post. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- "What does 'defund the police' mean? The rallying cry sweeping the US – explained". the Guardian. June 6, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- Durkin, Erin. "De Blasio confirms he'll cut $1B from NYPD budget". Politico PRO. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- Mays, Jeffery C. (August 10, 2020). "Who Opposes Defunding the N.Y.P.D.? These Black Lawmakers". The New York Times. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- "Minneapolis Council Moves To Defund Police, Establish 'Holistic' Public Safety Force". NPR.org. Retrieved November 5, 2020.

- Herndon, Astead W. (September 26, 2020). "How a Pledge to Dismantle the Minneapolis Police Collapsed". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 5, 2020.

- Allassan, Fadel. "Bernie Sanders pushes back on idea of abolishing police departments". Axios.

- Martin, Jonathan; Burns, Alexander; Kaplan, Thomas (June 8, 2020). "Biden Walks a Cautious Line as He Opposes Defunding the Police". The New York Times. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- Eliott C. McLaughlin. "Honoring the unforgivable: The horrific acts behind the names on America's infamous monuments and tributes". CNN. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- Taylor, Alan. "Photos: The Statues Brought Down Since the George Floyd Protests Began - The Atlantic". www.theatlantic.com. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- Mann, Ted (June 26, 2020). "Lincoln Statue With Kneeling Black Man Becomes Target of Protests". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- Plummer, Brenda Gayle (June 19, 2020). "Civil Rights Has Always Been a Global Movement: How Allies Abroad Help the Fight Against Racism at Home". Foreign Affairs. Vol. 99 no. 5. ISSN 0015-7120.

Global reactions to the Floyd murder were not simply responses to a single event. The world already knew about antiblack racism in the United States. Voter suppression, disproportionately affecting people of color, has no parallel in other democracies. The particulars of Floyd's murder, taking place against the backdrop of the pandemic, may well have been the dam-break moment for the global protest movement. But they are only part of the story. International solidarity with the African American civil rights struggle comes not from some kind of projection or spontaneous sentiment; it was seeded by centuries of black activism abroad and foreign concern about human rights violations in the United States.

- "Niet alleen Rutte is van mening veranderd: de steun voor traditionele Zwarte Piet is gedaald - weblog Gijs Rademaker". Een Vandaag. June 17, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- "Rutte: ik ben anders gaan denken over Zwarte Piet". NOS Nieuws. June 5, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- "How UK protesters are taking the spark of Black Lives Matter back to their hometowns". CNN. December 4, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- Weiss, Sabrina (June 12, 2020). "When we tear down racist statues, what should replace them?". Wired UK. ISSN 1357-0978. Retrieved August 31, 2020.