Songkhla Province

Songkhla (Thai: สงขลา, pronounced [sǒŋ.kʰlǎː], Southern Thai: สงขลา, pronounced [soŋ.kʰlaː], Malay: Singgora) is one of the southern provinces (changwat) of Thailand. Neighboring provinces are (from east clockwise) Satun, Phatthalung, Nakhon Si Thammarat, Pattani, and Yala. To the south it borders Kedah and Perlis of Malaysia.

Songkhla

สงขลา | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Panorama of Songkhla from Tang Kuan Hill | |

Flag  Seal | |

Map of Thailand highlighting Songkhla Province | |

| Country | Thailand |

| Capital | Songkhla |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Jaruwat Klaengkla (since October 2019)[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7,394 km2 (2,855 sq mi) |

| Area rank | Ranked 26th |

| Population (2018)[3] | |

| • Total | 1,432,628 |

| • Rank | Ranked 11th |

| • Density | 194/km2 (500/sq mi) |

| • Density rank | Ranked 15th |

| Human Achievement Index | |

| • HAI (2017) | 0.5955 "somewhat high" Ranked 30th |

| Time zone | UTC+7 (ICT) |

| Postal code | 90xxx |

| Calling code | 074 |

| ISO 3166 code | TH-90 |

| Website | www |

In contrast to most other provinces, the capital Songkhla is not the largest city in the province. The much newer city of Hat Yai, with a population of 359,813, is considerably larger, with twice the population of Songkhla (163,072). This often leads to the misconception that Hat Yai is the provincial capital.

Geography

The province is on the Malay Peninsula, on the coast of the Gulf of Thailand. The highest elevation is Khao Mai Kaeo at 821 meters.

In the north of the province is Songkhla Lake, the largest natural lake in Thailand. This shallow lake covers an area of 1,040 km2, and has a south–north extent of 78 kilometers. At its mouth on the Gulf of Thailand, near the city of Songkhla, the water becomes brackish.[5] A small population of Irrawaddy dolphins live in the lake, but are in danger of extinction due to accidental capture by the nets of the local fishing industry.

Songkhla Province hosts two national parks. San Kala Khiri covers 214 km2 of mountain highlands on the Thai-Malay border.[6] Khao Nam Khang, is also in the boundary mountains.[7] Chinese Communist guerrillas inhabited this region until the 1980s.

Within the boundaries of the city of Songkhla is Cape Samila Beach, the most popular beach in the province. The famous mermaid statue can be found here. The two islands Ko Nu and Ko Maew (Mouse and Cat Islands), not far from the beach, are also popular landmarks, and a preferred fishing ground. According to a local folk tale, a cat, mouse and dog were traveling on a Chinese ship, when they attempted to steal a crystal from a merchant. While trying to swim ashore, both the cat and the mouse drowned and became the two islands; the dog reached the beach, then died and become the hill Khao Tang Kuan. The crystal turned into the white sandy beach.[8]

Toponymy

The name Songkhla is actually the Thai corruption of Singgora (Jawi: سيڠڬورا); its original name means "the city of lions" in Malay (not to be confused with Singapura). This refers to a lion-shaped mountain near the city of Songkhla.

History

Songkhla was the seat of an old Malay Kingdom with heavy Srivijayan influence. In ancient times (200–1400 CE), Songkhla formed the northern extremity of the Malay Kingdom of Langkasuka. The city-state then succeeded as the Sultanate of Singgora, it later became a tributary of Nakhon Si Thammarat, suffering damage during several attempts to gain independence.

Archaeological excavations on the isthmus between Lake Songkhla and the sea reveal that in the 10th through the 14th century this was a major urbanized area, and a center of international maritime trade, in particular with Quanzhou in China. The long Sanskrit name of the state that existed there has been lost; its short Sanskrit name was Singhapura ("Lion City") (not to be confused with Singapura), a city state. The short vernacular name was Satingpra, coming from the Mon-Khmer sting/steng/stang (meaning "river") and the Sanskrit pura ("city").[9]:320–321 The ruins of the important port city of Satingpra are just few kilometres north of Songkhla city.[10]

Since the 18th century, Songkla has been firmly under Thai suzerainty. In 1909, Songkhla was formally annexed by Siam as part of Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909, negotiated with the British Empire, in which Siam gave up its claim to Kelantan in return for Britain recognizing Siam's right to the provinces north of that.

In the 18th century many Chinese immigrants, especially from Guangdong and Fujian, came to the province. Quickly rising to economic wealth, one of them won the bidding for the major tax farm of the province in 1769, establishing the Na Songkhla (from Songkhla) family as the most wealthy and influential. In 1777 the family also gained political power, when the old governor was dismissed and Luang Inthakhiri (Yiang, Chinese name Wu Rang (呉譲)) became the new governor. In 1786 the old governor started an uprising, which was put down after four months. The position was thereafter inherited in the family and was held by eight of his descendants until 1901, when Phraya Wichiankhiri (Chom) was honorably retired as part of the administrative reforms of Prince Damrong Rajanubhab. The family's former home was converted into the Songkhla National Museum in 1953.

Songkhla was the scene of heavy fighting when the Imperial Japanese Army invaded Thailand on 8 December 1941 and parts of the city were destroyed.

Demographics

Buddhists make up two-thirds to three-fourths of the population, most of whom are of native Thai or Thai Chinese descent.[12] One-fourth to one-third of the population are Muslim, most of them belong to a Thai-speaking Muslim group, called Sam-Sam ( 'mixed' ).[13] People claiming to be of Malay ethnicity make up a minority among the Muslim populace.[14] The Songkhla Malays are very similar in ethnicity and culture to the Malays of Kelantan, Malaysia. They speak the Patani Malay language, which differs from Bahasa Malay in vocabulary and pronunciation.

Symbols

The provincial seal shows a conch shell on a Phan (tray) with glass decorations. The origin of the conch shell is unclear, but the most widely adopted interpretation is that it was a decoration on the jacket of the Prince of Songkhla.

The provincial tree is the Sa-dao-thiam (Azadirachta excelsa).

Administrative divisions

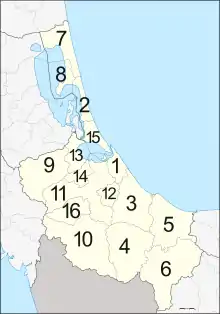

Provincial government

Songkhla is divided into 16 districts (amphoe), which are further subdivided into 127 subdistricts (tambon) and 987 villages (muban). The districts of Chana (Malay: Chenok), Thepa (Malay: Tiba) were detached from Mueang Pattani and transferred to Songkhla during the Thesaphiban reforms around 1900.

|

Local government

As of 26 November 2019 there are:[15] one Songkhla Provincial Administration Organisation (ongkan borihan suan changwat) and 48 municipal (thesaban) areas in the province. Songkhla and Hat Yai have city (thesaban nakhon) status.[16] Further 11 have town (thesaban mueang) status and there are 35 subdistrict municipalities (thesaban tambon). The non-municipal areas are administered by 92 Subdistrict Administrative Organisations - SAO (ongkan borihan suan tambon).[3]

Health

Songkhla is served by a larger number of public hospitals than private hospitals. The main hospitals for Songkhla Province is Hatyai Hospital and Songkhla Hospital, both operated by the Ministry of Public Health. Songklanagarind Hospital is also another major hospital located in Hat Yai, but is operated by the Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University which is the largest medical school in the South of Thailand.

Economy

Songkhla Province is an energy hub. It earns 100 billion baht each year from a gas separation plant, power generation, and oil. The gas separation plant sells 35 billion baht worth of gas per year to EGAT. Power generation accounts for 45 billion baht. Offshore oil rigs in the vicinity of Ko Nu produce 20,000 barrels of oil per day worth 30 billion baht per year. If a proposed coal-fired electrical generation plan in Thepha District goes ahead, energy earnings could rise to 300 billion baht per year.[17]

Transport

Road

Phetkasem Road, running all the way from Bangkok, ends at the border crossing to Malaysia in Sadao. Asian highway 2 and 18 also run through the province. Of note is the Tinsulanond Bridge, which crosses Songkhla Lake to connect the narrow land east of the lake at the coast with the main southern part of the province. With a length of 2.6 km it is the longest concrete bridge in Thailand. Built in 1986, the bridge consists of two parts. The southern 1,140 m connects Mueang district with the island Ko Yo, and the northern part of 1,800 m to Ban Khao Khiao.

Kanchanawanit Road, which runs from Songkhla town, though Hat Yai, and all the way to the Malaysian border at Sadao District, is considered the unofficial dividing line separating the Thai south from its deep south, Muslim-majority region.

Rail

The southern railway operated by the State Railway of Thailand runs through the province, and continues on into Malaysia, with Hat Yai Junction being the main railway station. It is a junction for the railway link to Malaysia through Padang Besar Town, where there are two stations: Padang Besar (Thai) on the Thai side and Padang Besar on the Malay side. Immigration is done on the Malay side. The other route from Hat Yai Junction goes further south to Pattani (Khok Pho), Yala, Tanyong Mat and Su-ngai Kolok. In the past, a railway line connected the town of Songkhla with Hat Yai, but it was closed in 1978 and is now partly dismantled and partly overgrown.[18]

Air

Songkhla is served by Hat Yai International Airport in Khlong Hoi Khong District.

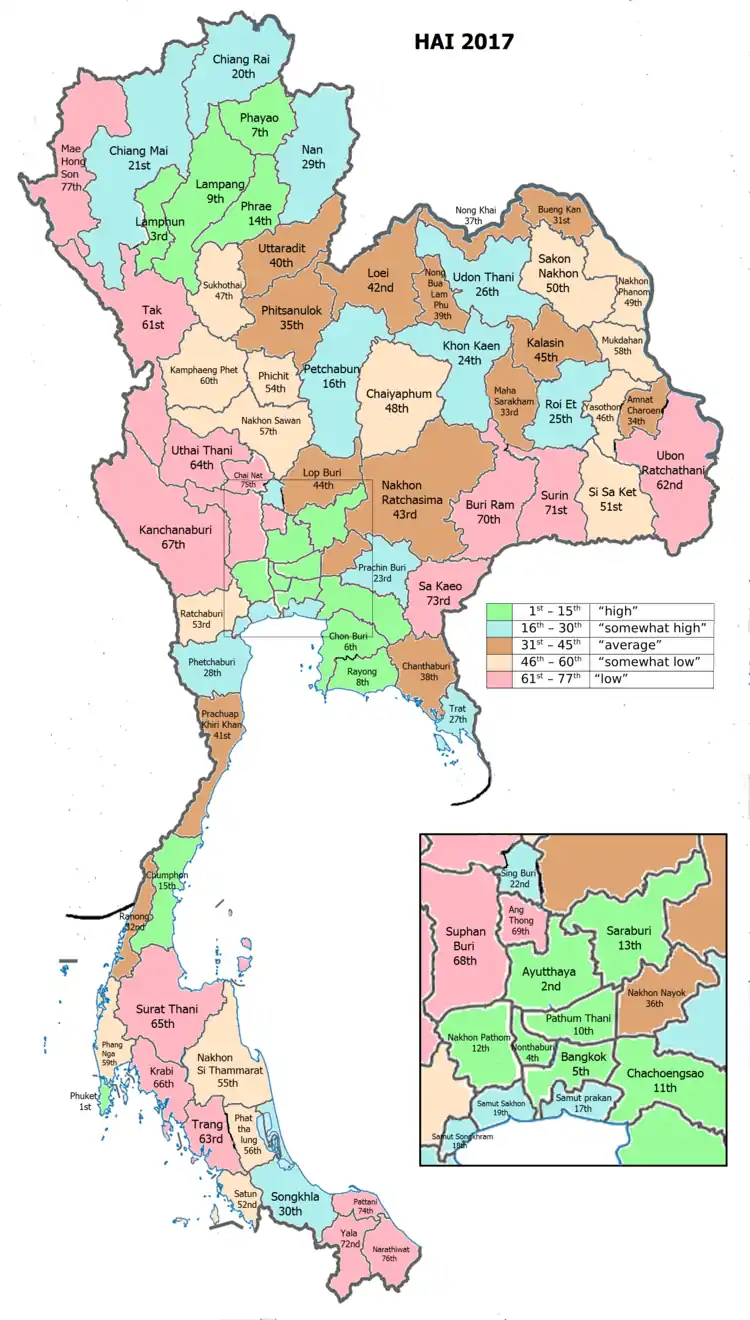

Human achievement index 2017

| Health | Education | Employment | Income |

| 24 | 19 | 72 | 19 |

| Housing | Family | Transport | Participation |

|

|

|

|

| 55 | 66 | 8 | 43 |

| Province Songkhla, with an HAI 2017 value of 0.5955 is "somewhat high", occupies place 30 in the ranking. | |||

Since 2003, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Thailand has tracked progress on human development at sub-national level using the Human achievement index (HAI), a composite index covering all the eight key areas of human development. National Economic and Social Development Board (NESDB) has taken over this task since 2017.[4]

| Rank | Classification |

| 1 - 15 | "high" |

| 16 - 30 | "somewhat high" |

| 31 - 45 | "average" |

| 45 - 60 | "somewhat low" |

| 61 - 77 | "low" |

| Map with provinces and HAI 2017 rankings |

|

Culture

The most important Buddhist temple of the province is Wat Matchimawat (also named Wat Klang), on Saiburi road in the city of Songkhla itself.

On the island Ko Yo within Songkhla lake, since being easily accessible via the Tinsulanond Bridge, the residents have started to sell the hand-woven fabric named Phathor Ko Yo. Also famous for the island is the local jackfruit variant named Jampada.

Held in the first night of October, the Chak Phra tradition is a Buddhist festival specific to the south of Thailand. It is celebrated with Buddha boat processions or sports events like a run up Khao Tang Kuan hill.

In September or October at the Chinese Lunar festival the Thai-Chinese present their offerings to the moon or Queen of the heavens in gratitude for past and future fortunes.

Military rule

Songkhla was not initially affected by the outbreak of Pattani Separatism, which began in 2004. However, bombs planted in 2005 and 2007 stoked fears the insurgency might spread to Songkhla Province.

As of 2018, the provisions of Thailand's Internal Security Act remain imposed on the districts of Chana, Na Thawi, Saba Yoi, and Thepha for reasons of national security. All but Chana share a border with Malaysia or Pattani Province (Malay majority). Internal security restrictions, maintained by Thailand's Internal Security Operations Command (ISOC) can result in curfews, prohibited entry, or prohibited transport of goods. It is considered one step below the imposition of full martial law.[19][20]

Sport

- Football

Songkhla football club participates in Thai League 4 Southern Region, the 4th tier of Thai football league system. The Samila Mermaid (Thai:เงือกสมิหลา) plays their home matches at Tinsulanon Stadium.[21][22][23]

Notes

Reports (data) from Thai government are "not copyrightable" (Public Domain), Copyright Act 2537 (1994), section 7.

References

- "ประกาศสำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี เรื่อง แต่งตั้งข้าราชการพลเรือนสามัญ" [Announcement of the Prime Minister's Office regarding the appointment of civil servants] (PDF). Royal Thai Government Gazette. 136 (Special 242 Ngor). 24. 28 September 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- Advancing Human Development through the ASEAN Community, Thailand Human Development Report 2014, table 0:Basic Data (PDF) (Report). United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Thailand. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-974-680-368-7. Retrieved 17 January 2016, Data has been supplied by Land Development Department, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives, at Wayback Machine.

- "รายงานสถิติจำนวนประชากรและบ้านประจำปี พ.ศ.2561" [Statistics, population and house statistics for the year 2018]. Registration Office Department of the Interior, Ministry of the Interior (in Thai). 31 December 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- Human achievement index 2017 by National Economic and Social Development Board (NESDB), pages 1-40, maps 1-9, retrieved 14 September 2019, ISBN 978-974-9769-33-1

- "Songkhla Lake". Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT). Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- "San Kala Khiri National Park". Department of National Parks (DNP) Thailand. Archived from the original on 21 June 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- "Khao Nam Khang National Park". Department of National Parks (DNP) Thailand. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- "Laem Samila". Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT). Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- Stargardt, Janice (2001). "Behind the Shadows: Archaeological Data on Two-Way Sea Trade Between Quanzhou and Satingpra, South Thailand, 10th-14th century". In Schottenhammer, Angela (ed.). The Emporium of the World: Maritime Quanzhou, 1000-1400. Volume 49 of Sinica Leidensia. Brill. pp. 309–393. ISBN 90-04-11773-3.

- Michel Jacq-Hergoualc'h (2002). BRILL (ed.). The Malay Peninsula: Crossroads of the Maritime Silk-Road (100 Bc-1300 Ad). Translated by Victoria Hobson. pp. 411–416. ISBN 90-04-11973-6.

- "เอกสารตรวจราชการ รอบ 2 ปี 2562". Songkhla Provincial Public Health Office. 26 July 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Geoffrey Benjamin, Cynthia Chou (26 August 2002). Tribal Communities in the Malay World. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 80. ISBN 981-230-166-6.

- Kobkua Suwannathat-Pian (2000). The Historical Development of Thai-Speaking Muslim Communities in Southern Thailand and Northern Malaysia. Civility and Savagery: Social Identity in Tai States. Routledge. p. 173. ISBN 0-7007-1173-2.

- songkhla.xls

- "Number of local government organizations by province". dla.go.th. Department of Local Administration (DLA). 26 November 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

57 Songkhla: 1 PAO, 2 City mun., 11 Town mun., 35 Subdistrict mun., 92 SAO.

- "พระราชกฤษฎีกา จัดตั้งเทศบาลนครหาดใหญ่ จังหวัดสงขลา พ.ศ.๒๕๓๘" [Royal Decree Establishing Hat Yai city municipality, Songkhla province, B.E.2538 (1995)] (PDF). Royal Thai Government Gazette. 112 (40 Kor): 19–23. 24 September 1995. Retrieved 10 March 2020, effectively on 25 September 1995

- Samart, Somchai (2015-08-03). "Power plant to fulfil dream to be 'energy city'". The Nation. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- 2Bangkok.com - The Songkhla to Hat Yai rail line Archived December 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Raksaseri, Kornchanok (8 January 2018). "Isoc power boost 'not political'". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- "Thai districts impose martial law". BBC. 2005-11-03.

- "คัมแบ็กรอบ 7 ปี! สงขลา เอฟซีเตรียมส่งทีมลุย TA ซีซั่นหน้า".

- "10 เหตุผลที่"เงือกสมิหลา"ใช้สนามติณเป็นรังเหย้า".

- "เงือกสมิหลา สงขลาเอฟซี กับการมาสู่เส้นทางลีกอาชีพภาคใหม่ของทีมประจำจังหวัด".

External links

- Provincial website (Thai)