Agaw people

The Agaw (Ge'ez: አገው Agäw, modern Agew) are a Cushitic ethnic group inhabiting Ethiopia and neighboring Eritrea. Ethnically and culturally they are part of a wider population of Cushitic peoples, though they are most closely related to the Qemant people.

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Horn of Africa | |

| 763,00[1] | |

| 110,000[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Agaw • Amharic • Tigrinya | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (Ethiopian Orthodox · Eritrean Orthodox · Catholic), Judaism, Islam (Sunni) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Afar • Beja • Beta Israel • Oromo • Saho • Somali • other Cushitic peoples[3] | |

They speak the Agaw languages, which belong to the Cushitic branch of the Afroasiatic language family, and have a high degree of mutual intelligibility between them. As the Agaw are a minority population in both Ethiopia and Eritrea, they face substantial pressures of assimilation, especially from the Amhara, and the Agaw languages are now considered critically endangered.

The Agaw peoples in general were historically noted by travelers and outside observers to have practiced what some described as a “Hebraic religion”, similar to the Qemant, though some practiced Ethiopian Orthodoxy, and many were Beta Israel Jews. A small minority have adopted Islam in the last few centuries. Thousands of Agaw Beta Israel converted to Christianity in the 19th and early 20th century (both voluntarily and forcibly), becoming the Falash Mura, though many are now returning to Judaism.

History

The Agaw are perhaps first mentioned in the third-century Monumentum Adulitanum, an Aksumite inscription recorded by Cosmas Indicopleustes in the sixth century. The inscription refers to a people called "Athagaus" (or Athagaous), perhaps from ʿAd Agaw, meaning "sons[4] of Agaw."[5] The Athagaous first turn up as one of the peoples conquered by the unknown king who inscribed the Monumentum Adulitanum.[6] The Agaw are later mentioned in an inscription of the fourth century emperor Ezana of Axum[5] and the sixth-century emperor Kaleb of Axum. Based on this evidence, a number of experts embrace a theory first stated by Edward Ullendorff and Carlo Conti Rossini that they are the original inhabitants of much of the northern Ethiopian Highlands, and were either forced out of their original settlements or assimilated by Semitic-speaking Tigrayans, Amharas and Tigrinyas .[7] Cosmas Indicopleustes also noted in his Christian Topography that a major gold trade route passed through the region "Agau". The area referred to seems to be an area east of the Tekezé River and just south of the Semien Mountains, perhaps around Lake Tana.[5]

They currently exist in a number of scattered enclaves, which include the Bilen in and around Keren, Eritrea; the Qemant people (including the now-relocated Beta Israel), who live around Gondar in the North Gondar Zone of the Amhara Region, west of the Tekezé River and north of Lake Tana; a number of Agaw live south of Lake Tana, around Dangila in the Agew Awi Zone of the Amhara Region; and another group live around Soqota in the former province of Wollo, now part of the Amhara Region, along its border with the Tigray Region.

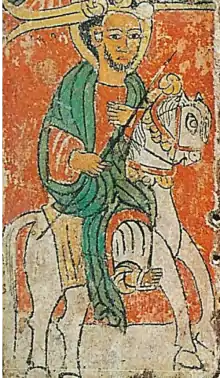

The Cushitic speaking Agaw people ruled during the Zagwe dynasty of Ethiopia from about 900 to 1270. The name of the dynasty itself comes from the Ge'ez phrase Ze-Agaw (meaning "of the Agaw"), and refers to the Agaw people.

Language

The Agaw speak Agaw languages. They are a part of the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic family. Many also speak other languages such as Amharic, Tigrinya and/or Tigre.

Subgroups

Notable Agaw people

- Mara Takla Haymanot - Emperor of Ethiopia who founded the Zagwe dynasty by 1137

- Gebre Mesqel Lalibela - Emperor of Ethiopia who is credited with having constructed the rock-hewn churches of Lalibela

- Yetbarak - Emperor of Ethiopia, the last ruler from the Zagwe dynasty who reigned up to 1270

See also

References

- "Awi". Joshua Project. Venture Center. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- "Bilen". Joshua Project. Venture Center. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- Joireman, Sandra F. (1997). Institutional Change in the Horn of Africa: The Allocation of Property Rights and Implications for Development. Universal Publishers. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-58112-000-4.

- Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2003. p. 117

- Uhlig, Siegbert, ed. Encyclopaedia: A-C. p. 142.

- Munro-Hay, Stuart. Aksum: an African Civilization of Late Antiquity (Edinburgh: University Press, 1991), p. 187

- Taddesse Tamrat, Church and State in Ethiopia (1270 - 1527) (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), p. 26.