Afar people

The Afar (Afar: Qafár), also known as the Danakil, Adali and Odali, are an ethnic group inhabiting the Horn of Africa. They primarily live in the Afar Region of Ethiopia and in northern Djibouti, as well as the entire southern coast of Eritrea. The Afar speak the Afar language, which is part of the Cushitic branch of the Afroasiatic family. Afars are the only Horners whose traditional territories borders both the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, and like the Issa clan they do not trace ancestry to Arabia.[3]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 2.5 million [1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Horn of Africa | |

| 1,840,000[1] | |

| 431,000[1] | |

| 335,000[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Afar: Qafaraf Afar language | |

| Religion | |

| Islam (Sunni, nondenominational Muslim) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

History

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Djibouti |

|

| Prehistory |

| Antiquity |

|

| Middle Ages |

|

| Colonial period |

|

| Modern period |

| Republic of Djibouti |

|

|

Origins

The Afar traditions include conversion to Islam from the 7th century onwards, with genealogies tracing lineage back to ancestors from Arabian Peninsula. Mixtures and circulations between the two shores of the Red Sea and inside the Horn are certain even if we are not able to specify them. According to linguistic scholars, the Afars and the Saho are the first peoples inhabiting the horn of Africa. Bones and traces of prehistoric peoples can be found in the Afar Region and their language forms a distinct whole within the Cushitic languages which later split into modern forms such as Oromo, Somali, Beja, Agaw, Afar, Saho and Sidamo. The Afars are described by Herodotus as being Ethiopian "troglodytes" living in caves along the Red Sea that the Garamantes hunted. The word "Afar" undoubtedly has a Berber origin, as this word means "inhabitant of caves" which translates well the troglodyte habitat that Herodotus attributes to them. This word is not attested in the Afar language (referred to as "Adal") according to some theories on the etymology of this word. The name may have been given by the Garamante Berbers who named them so because of their troglodyte habitat.

Early history

The earliest surviving written mention of the Afar is from the 13th-century Andalusian writer Ibn Sa'id, who reported that they inhabited the area around the port of Suakin, as far south as Mandeb, near Zeila.[4] They are mentioned intermittently in Ethiopian records, first as helping Emperor Amda Seyon in a campaign beyond the Awash River, then over a century later when they assisted Emperor Baeda Maryam when he campaigned against their neighbors the Dobe'a.[5]

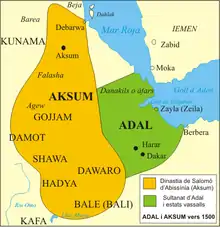

Along with the closely related Somali and other adjacent Afro-Asiatic-speaking Muslim peoples, the Afar are also associated with the medieval Adal Sultanate that controlled large parts of the northern Horn of Africa. After the death of the Adal leader Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi, Afar settlements were overtaken in Hararghe by the result of the Oromo migrations. The Issa Somali also took advantage of the crippled Afar and occupied large swaths of their territory in the north west of East Africa.[6]

Aussa States

Afar society has traditionally been organized into independent kingdoms, each ruled by its own Sultan. Among these were the Sultanate of Aussa, Sultanate of Girrifo, Sultanate of Dawe, Sultanate of Tadjourah, Sultanate of Rahaito, and Sultanate of Goobad.[7] In 1577, the Adal leader Imam Muhammed Jasa moved his capital from Harar to Aussa in modern Afar region. In 1647, the rulers of the Emirate of Harar broke away to form their own polity. Harari imams continued to have a presence in the southern Afar Region until they were overthrown in the eighteenth century by the Mudaito dynasty of Afar who later established the Sultanate of Aussa.[8] The primary symbol of the Sultan was a silver baton, which was considered to have magical properties.[9]

Pre-19th century

According to Elisée Reclus, Afar are divised into two groups, the Asaimara and the Adoimara, these groups are further subdivided into upwards of one hundreds and fifty sub-tribes according to their interests but all combine against the common enemy. The Modaitos who occupy the region of the lower Awash are the most powerful and no European traversed their territory without claiming the right of hospitality or the brotherhood of blood. Irregular climate often causes the Afar to migrate into Issa territory when their pastures are dry and they reciprocate the hospitality to maintain harmony.[10] From the 1840s, some Afar's help Europeans by providing, for a fee, the security of Western caravans that circulated between the southern coast of the Red Sea and central Ethiopia. Towards the end of the 19th century, the sultanates of Raheita and Tadjoura on the coasts of the Red Sea are then colonized between European powers: Italy forms Italian Eritrea with Assab and Massawa, and France the French Somaliland in Djibouti, but the inland Aussa in the south was able to maintain its independence for longer. Even comparatively fertile and located on the Awash River, it was demarcated from the outside by surrounding desert areas. It was not until 1895 that Ethiopia, under Emperor Menelik II of Ethiopia, sent an army from Shewa against Aussa on the grounds that the Sultan had allied himself with the Italian colonizers. As a result, the sultanate paid tribute to Ethiopia, but retained extensive autonomy.

Afar Liberation Front

When a modern administrative system was introduced in Ethiopia after the Second World War, the Afar areas controlled by Ethiopia were divided into the provinces of Eritrea, Tigray, Wollo, Shewa and Hararge. Tribal leaders, elders and religious and other dignitaries of the Afar tried unsuccessfully in the government from 1961 to end this division. Following an unsuccessful rebellion led by the Afar Sultan, Alimirah Hanfare, the Afar Liberation Front was founded in 1975 to promote the interests of the Afar people. Sultan Hanfadhe was shortly afterwards exiled to Saudi Arabia. Ethiopia's then-ruling communist Derg regime later established the Autonomous Region of Assab (now called Aseb and located in Eritrea), although low level insurrection continued until the early 1990s. In Djibouti, a similar movement simmered throughout the 1980s, eventually culminating in the Afar Insurgency in 1991. After the fall of the Derg that same year, Sultan Hanfadhe returned from exile.

In March 1993, the Afar Revolutionary Democratic Front (ARDUF) was established. It constituted a coalition of three Afar organizations: the Afar Revolutionary Democratic Unity Union (ARDUU), founded in 1991 and led by Mohamooda Gaas (or Gaaz); the Afar Ummatah Demokrasiyyoh Focca (AUDF); and the Afar Revolutionary Forces (ARF). A political party, it aims to protect Afar interests. As of 2012, the ARDUF is part of the United Ethiopian Democratic Forces (UEDF) coalition opposition party.[11]

Demographics

Geographical distribution

The Afar principally reside in the Danakil Desert in the Afar Region of Ethiopia, as well as in Eritrea and Djibouti. They number 2,276,867 people in Ethiopia (or 2.73% of the total population), of whom 105,551 are urban inhabitants, according to the most recent census (2007).[12] The Afar make up over a third of the population of Djibouti, and are one of the nine recognized ethnic divisions (kililoch) of Ethiopia.[13]

Language

Afars speak the Afar language as a mother tongue. It is part of the Cushitic branch of the Afroasiatic language family.

The Afar language is spoken by ethnic Afars in the Afar Region of Ethiopia, as well as in southern Eritrea and northern Djibouti. However, since the Afar are traditionally nomadic herders, Afar speakers may be found further afield.

Together, with the Saho language, Afar constitutes the Saho–Afar dialect cluster.

Religion

Afar people are predominantly Muslim. They have a long association with Islam through the various local Muslim polities and practice the Sunni form of Islam, or non-denominational Islam.[7] The Afar mainly follow the Shafi'i school of Sunni Islam. Sufi orders like the Qadiriyya are also widespread among the Afar. Afar religious life is somewhat syncretic with a blend of Islamic concepts and pre-Islamic ones such as rain sacrifices on sacred locations, divination, and folk healing.[14] Another strand or self-identification adopted by the Afar is that of the non-denominational Muslim.[15]

Culture

Socially, they are organized into clan families led by elders and two main classes: the asaimara ('reds') who are the dominant class politically, and the adoimara ('whites') who are a working class and are found in the Mabla Mountains.[16] Clans can be fluid and even include outsiders like the (Issa clan).[14]

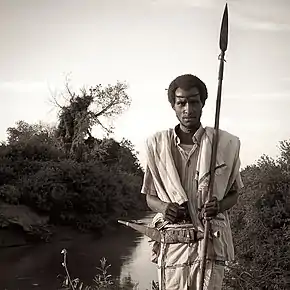

In addition, the Afar are reputed for their martial prowess. Men traditionally carry the jile, a famous curved knife. They also have an extensive repertoire of battle songs.[7]

The Afar are mainly livestock holders, primarily raising camels but also tending to goats, sheep, and cattle. However, shrinking pastures for their livestock and environmental degradation have made some Afar instead turn to cultivation, migrant labor, and trade. The Ethiopian Afar have traditionally engaged in salt trading but recently Tigrayans have taken much of this occupation.[14]

Notes

- "Ethnologue aar". Ethnologue. SIL International. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- Joireman, Sandra F. (1997). Institutional Change in the Horn of Africa: The Allocation of Property Rights and Implications for Development. Universal-Publishers. p. 1. ISBN 1581120001.

- Fairhead, J. D., and R. W. Girdler. "A discussion on the structure and evolution of the Red Sea and the nature of the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden and Ethiopia rift junction-The seismicity of the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden and Afar triangle." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences 267.1181 (1970): 49–74.

- Richard Pankhurst, The Ethiopian Borderlands (Lawrenceville: Red Sea Press, 1997), p. 60

- Pankhurst, Borderlands, pp. 61-67, 106f.

- Yasin, Yasin (2010). Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti. UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG. p. 72.

- Matt Phillips, Jean-Bernard Carillet, Lonely Planet Ethiopia and Eritrea, (Lonely Planet: 2006), p. 301.

- Page, Willie. Encyclopedia of africaN HISTORY andCULTURE (PDF). Facts on File inc. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- Trimingham, p. 262.

- Reclus, Elisée (1886). The Earth and Its Inhabitants ...: North-east Africa. D. Appleton. p. 191.

- Ethiopia - Political Parties, Accessed: 1-07-2006.

- "Country level" Archived 16 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Table 3.1, p.73.

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- Skutsch, Carl, ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. 1. New York: Routledge. pp. 11, 12. ISBN 1-57958-468-3.

- Brugnatelli, Vermondo. "Arab-Berber contacts in the Middle Ages and Ancient Arabic dialects: new evidence from an old Ibadite religious text." African Arabic: approaches to dialectology. Berlin: de Gruyter (2013): 271–291.

- Uhlig, Siegbert (2003). Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 103. ISBN 978-3-447-04746-3.

References

- Mordechai Abir, The era of the princes: the challenge of Islam and the re-unification of the Christian empire, 1769-1855 (London: Longmans, 1968).

- J. Spencer Trimingham, Islam in Ethiopia (Oxford: Geoffrey Cumberlege for the University Press, 1952).

Further reading

- Jeangene Vilmer, Jean-Baptiste; Gouery, Franck (2011). Les Afars d'Éthiopie. Dans l'enfer du Danakil. ISBN 9782352701088. Archived from the original on 31 July 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Afar people. |