Polacanthinae

Polacanthinae is a grouping of ankylosaurs, possibly primitive nodosaurids. Polacanthines are late Jurassic to early Cretaceous in age, and appear to have become extinct about the same time a land bridge opened between Asia and North America.[1]

| Polacanthines | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeletons of Gastonia burgei, North American Museum of Ancient Life | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | †Ornithischia |

| Suborder: | †Ankylosauria |

| Family: | †Nodosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Polacanthinae Wieland, 1911 |

| Genera | |

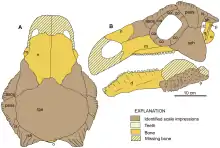

Polacanthines were somewhat more lightly armoured than more advanced ankylosaurids and nodosaurids. Their spikes were made up of thin, compact bone with less reinforcing collagen than in the heavily armoured nodosaurids. The relative fragility of polacanthine armour suggests that it may have been as much for display as defense.[2]

Classification

The family Polacanthidae was named by Wieland in 1911 to refer to a group of ankylosaurs which seemed to him intermediate between the ankylosaurids and nodosaurids. This grouping was ignored by most researchers until the late 1990s, when it was used as a subfamily (Polacanthinae) by Kirkland for a natural group recovered by his 1998 analysis suggesting that Polacanthus, Gastonia, and Mymoorapelta were closely related within the family Ankylosauridae. Kenneth Carpenter resurrected the name Polacanthidae for a similar group which he also found to be closer to ankylosaurids than to nodosaurids. Carpenter became the first to define Polacanthidae as all dinosaurs closer to Gastonia than to either Edmontonia or Euoplocephalus.[3] Most subsequent researchers placed polacanthines as primitive ankylosaurids, though mostly without any rigorous study to demonstrate this idea. The first comprehensive study of 'polacanthid' relationships, published in 2011, found that they are either an unnatural grouping of primitive nodosaurids, or a valid subfamily at the base of Nodosauridae.[4]

The clade Nodosauridae was first defined by Paul Sereno in 1998 as "all ankylosaurs closer to Panoplosaurus than to Ankylosaurus," a definition followed by Vickaryous, Teresa Maryańska, and Weishampel in 2004. Vickaryous et al. considered two genera of nodosaurids to be of uncertain placement (incertae sedis): Struthiosaurus and Animantarx, and considered the most primitive member of the Nodosauridae to be Cedarpelta.[5] The cladogram below follows the most resolved topology from a 2013 analysis,[6] which used an expanded version of the data presented by Richard S. Thompson and colleagues (2011).[4] The placement of Polacanthinae follows its original definition by Kenneth Carpenter in 2001.[3]

| Nodosauridae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Biogeography

The near simultaneous appearance of nodosaurids in both North America and Europe is worthy of consideration. Europelta is the oldest nodosaurid from Europe, it is derived from the lower Albian Escucha Formation. The oldest western North American nodosaurid is Sauropelta, from the lower Albian Little Sheep Mudstone Member of the Cloverly Formation, at an age of 108.5±0.2 million years. Eastern North American fossils seem older. Teeth of Priconodon crassus from the Arundel Clay of the Potomac Group of Maryland, which dates near the Aptian–Albian boundary. The Propanoplosaurus hatchling from the base of the underlying Patuxent Formation, date to the upper Aptian, making Propanoplosaurus the oldest nodosaurid.[7]

Polacanthines are known from pre-Aptian fauna from both Europe and North America. The timing of the appearance of nodosaurids on both continents indicates the origins of the clade preceded the isolation of North America and Europe, pushes the groups date of evolution back to at least the "middle" Aptian. The separation of advanced nodosaurids into European Struthiosaurinae and North American Nodosaurinae by the end of the Aptian provides a revised date for the isolation of the continents from each other with rising sealevel.[7]

See also

References

- Kirkland, J. I. (1996). Biogeography of western North America's mid-Cretaceous faunas - losing European ties and the first great Asian-North American interchange. J. Vert. Paleontol. 16 (Suppl. to 3): 45A.

- Hayashi, S.; Carpenter, K.; Scheyer, T.M.; Watabe, M.; Suzuki, D. (2010). "Function and evolution of ankylosaur dermal armor" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 55 (2): 213–228. doi:10.4202/app.2009.0103.

- Carpenter K (2001). "Phylogenetic analysis of the Ankylosauria". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 455–484. ISBN 0-253-33964-2.

- Thompson, R.S., Parish, J.C., Maidment, S.C.R. and Barrett, P.M. (2011). "Phylogeny of the ankylosaurian dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Thyreophora)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 10 (2): 301–312. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.569091.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Vickaryous, M. K., Maryanska, T., and Weishampel, D. B. (2004). Chapter Seventeen: Ankylosauria. in The Dinosauria (2nd edition), Weishampel, D. B., Dodson, P., and Osmólska, H., editors. University of California Press.

- Jingtao, Y.; Hailu, Y.; Daqing, L.; Delai, K. (2013). "First discovery of polacanthine ankylosaur dinosaur in Asia". Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 51 (4): 265–277.

- Kirkland, J. I.; Alcalá, L.; Loewen, M. A.; Espílez, E.; Mampel, L.; Wiersma, J. P. (2013). Butler, Richard J (ed.). "The Basal Nodosaurid Ankylosaur Europelta carbonensis n. gen., n. sp. From the Lower Cretaceous (Lower Albian) Escucha Formation of Northeastern Spain". PLoS ONE. 8 (12): e80405. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080405. PMC 3847141. PMID 24312471.