Anuradhapura Kingdom

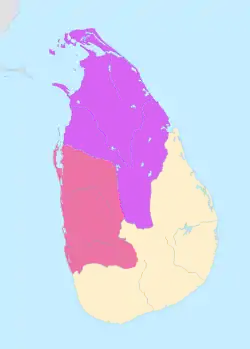

The Anuradhapura Kingdom (Sinhala: අනුරාධපුර රාජධානිය, translit: Anurādhapura Rājadhāniya), named for its capital city, was the first established kingdom in ancient Sri Lanka and Sinhalese people. Founded by King Pandukabhaya in 377 BC, the kingdom's authority extended throughout the country, although several independent areas emerged from time to time, which grew more numerous towards the end of the kingdom. Nonetheless, the king of Anuradhapura was seen as the supreme ruler of the country throughout the Anuradhapura period. Buddhism played a strong role in the Anuradhapura period, influencing its culture, laws, and methods of governance.[N 2] Society and culture were revolutionized when the faith was introduced during the reign of King Devanampiya Tissa; this cultural change was further strengthened by the arrival of the Tooth Relic of the Buddha in Sri Lanka and the patronage extended by her rulers.[4]

Kingdom of Anuradhapura අනුරාධපුර රාජධානිය | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 377 BC–1017 AD | |||||||||

The flag used by Dutthagamani and subsequent rulers.[N 1] | |||||||||

Kingdom of Anuradhapura Principality of Malaya (Malaya Rata) Principality of Ruhuna (Ruhunu Rata) | |||||||||

| Capital | Anuradhapura | ||||||||

| Common languages | Sinhala | ||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism & Hinduism (Until 267 BC)[2][3] | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

• 377 BC-367 BC | Pandukabhaya | ||||||||

• 982–1017 | Mahinda V | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 377 BC | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1017 AD | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 65,610 km2 (25,330 sq mi) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| Historical states of Sri Lanka |

|

|

|

Invasions from South India were a constant threat throughout the Anuradhapura period. Rulers such as Dutthagamani, Valagamba, and Dhatusena are noted for defeating the South Indians and regaining control of the kingdom. Other rulers who are notable for military achievements include Gajabahu I, who launched an invasion against the invaders, and Sena II, who sent his armies to assist a Pandyan prince.

Because the kingdom was largely based on agriculture, the construction of irrigation works was a major achievement of the Anuradhapura Kingdom, ensuring water supply in the dry zone and helping the country grow mostly self-sufficient. Several kings, most notably Vasabha and Mahasena, built large reservoirs and canals, which created a vast and complex irrigation network in the Rajarata area throughout the Anuradhapura period. These constructions are an indication of the advanced technical and engineering skills used to create them. The famous paintings and structures at Sigiriya; the Ruwanwelisaya, Jetavana stupas, and other large stupas; large buildings like the Lovamahapaya; and religious works (like the numerous Buddha statues) are landmarks demonstrating the Anuradhapura period's advancement in sculpting.

The city of Anuradhapura

In 543 BC, prince Vijaya (543–505 BC) arrived in Sri Lanka, having been banished from his homeland in Kalinga. He eventually brought the island under his control and established himself as king. After this, his retinue established villages and colonies throughout the country. One of these was established by Anuradha, a minister of King Vijaya, on the banks of a stream called Kolon and was named Anuradhagama.[5]

In 377 BC, King Pandukabhaya (437–367 BC) made it his capital and developed it into a prosperous city.[6][7] Anuradhapura (Anurapura) was named after the minister who first established the village and after a grandfather of Pandukabhaya who lived there. The name was also derived from the city's establishment on the auspicious asterism called Anura.[8] Anuradhapura was the capital of all the monarchs who ruled the country in the Anuradhapura Kingdom, with the exception of Kashyapa I (473–491), who chose Sigiriya to be his capital.[9] The city is also marked on Ptolemy's world map.[10]

History

King Pandukabhaya, the founder and first ruler of the Anuradhapura Kingdom, fixed village boundaries in the country and established an administration system by appointing village headmen. He constructed hermitages, houses for the poor, cemeteries, and irrigation tanks.[11] He brought a large portion of the country under the control of the Anuradhapura Kingdom. However, it was not until the reign of Dutthagamani (161–137 BC) that the whole country was unified under the Anuradhapura Kingdom.[12] He defeated 32 rulers in different parts of the country before he killed Elara, the South Indian ruler who was occupying Anuradhapura, and ascended to the throne.[13] The chronicle Mahavamsa describes his reign with much praise, and devotes 11 chapters out of 37 for his reign.[14] He is described as both a warrior king and a devout Buddhist.[15] After unifying the country, he helped establish Buddhism on a firm and secure base, and built several monasteries and shrines including the Ruwanweli Seya[16] and Lovamahapaya.[17]

Another notable king of the Anuradhapura Kingdom is Valagamba (103, 89–77 BC), also known as Vatthagamani Abhaya, who was overthrown by five invaders from South India. He regained his throne after defeating these invaders one by one and unified the country again under his rule.[18] Saddha Tissa (137–119 BC), Mahaculi Mahatissa (77–63 BC), Vasabha (67–111), Gajabahu I (114–136), Dhatusena (455–473), Aggabodhi I (571–604) and Aggabodhi II (604–614) were among the rulers who held sway over the entire country after Dutthagamani and Valagamba. Rulers from Kutakanna Tissa (44–22 BC) to Amandagamani (29–19 BC) also managed to keep the whole country under the rule of the Anuradhapura Kingdom.[19] Other rulers could not maintain their rule over the whole island, and independent regions often existed in Ruhuna and Malayarata (hill country) for limited periods. During the final years of the Anuradhapura Kingdom, rebellions sprang up and the authority of the kings gradually declined.[20] By the time of Mahinda V (982–1017), the last king of the Anuradhapura Kingdom, the rule of the king had become so weak that he could not even properly organize the collection of taxes.[21]

During the times of Vasabha, Mahasena (274–301) and Dhatusena, the construction of large irrigation tanks and canals was given priority. Vasabha constructed 11 tanks and 12 canals,[22] Mahasen constructed 16 tanks and a large canal,[23] and Dhatusena built 18 tanks.[24] Most of the other kings have also built irrigation tanks throughout Rajarata, the area around Anuradhapura. By the end of the Anuradhapura Kingdom, a large and intricate irrigation network was available throughout Rajarata to support the agriculture of the country.[25]

Arrival of Buddhism

One of the most notable events during the Anuradhapura Kingdom was the introduction of Buddhism to the country. A strong alliance existed between Devanampiya Tissa (250–210 BC) and Ashoka of India,[26] who sent Arahat Mahinda, four monks, and a novice being sent to Sri Lanka.[27] They encountered Devanampiya Tissa at Mihintale. After this meeting, Devanampiya Tissa embraced Buddhism and the order of monks was established in the country.[28] Devanampiya Tissa, guided by Arahat Mahinda, took steps to firmly establish Buddhism in the country.[29]

Soon afterwards, the bhikkhuni Sanghamitta arrived from India in order to establish the Bhikkhuni sasana (order of nuns) in the country.[30] She brought along with her a sapling from the Sri Maha Bodhi, the tree under which the Buddha attained enlightenment, which was then planted in Anuradhapura.[31] Devanampiya Tissa bestowed on his kingdom the newly planted Jaya Sri Maha Bodhi.[32] Thus this is the establishment of Buddhism in Sri Lanka.

Arrival of the Sacred Tooth Relic

During the reign of Kithsirimevan (301–328), Sudatta, the sub king of Kalinga, and Hemamala brought the Tooth Relic of the Buddha to Sri Lanka because of unrest in their country.[33] Kithsirimevan carried it in procession and placed the relic in a mansion named Datadhatughara.[34] He ordered this procession to be held annually, and this is still done as a tradition in the country. The Tooth Relic of the Buddha soon became one of the most sacred objects in the country, and a symbol of kingship. The person who was in possession of the Tooth Relic would be the rightful ruler of the country.[35] Therefore, it was often enshrined within the royal palace itself.[36]

Invasions

Several invasions have been made against the Anuradhapura Kingdom, all of which were launched from South India. The first invasion recorded in the history of the country is during the reign of Suratissa (247–237 BC), where he was overthrown by two horse dealers from South India named Sena and Guththika. After ruling the country for 22 years, they were defeated by Asela (215–205 BC), who was in turn overthrown by another invasion led by a Chola prince named Elara (205–161 BC).[37] Elara ruled for 44 years before being defeated by Dutthagamani (Duttugamunu) [38] However, the Mahavamsa records that these foreign kings ruled the country fairly and lawfully.[37]

.jpg.webp)

The country was invaded again in 103 BC by five Dravidian chiefs, Pulahatta, Bahiya, Panya Mara, Pilaya Mara and Dathika, who ruled until 89 BC when they were defeated by Valagamba. Another invasion occurred in 433, and the country fell under the control of six rulers from South India. These were Pandu, Parinda, Khudda Parinda, Tiritara, Dathiya and Pithiya, who were defeated by Dhathusena who regained power in 459.[39] More invasions and raids from South India occurred during the reigns of Sena I (833–853)[40] and Udaya III (935–938).[41] The final invasion during the Anuradhapura Kingdom, which ended the kingdom and left the country under the rule of the Cholas, took place during the reign of Mahinda V.[42]

However, none of these invaders could extend their rule to Ruhuna, the southern part of the country, and Sri Lankan rulers and their heirs always organized their armies from this area and managed to regain their throne. Throughout the history of Sri Lanka, Ruhuna served as a base for resistance movements.[19]

Fall of Anuradhapura

Mahinda V (981-1017) distracted by a revolt of his own Dravidian mercenary troops fled to the south-eastern province of Rohana.[42] The Mahavamsa describes the rule of Mahinda V as weak, and the country was suffering from poverty by this time. It further mentions that his army rose against him due to lack of wages.[21] Taking advantage of this internal strife Chola Emperor Rajaraja I invaded Anuradhapura sometime in 993 AD and conquered the northern part of the country and incorporated it into his kingdom as a province named "Mummudi-sola-mandalam" after himself.[43] Rajendra Chola I son of Rajaraja I, launched a large invasion in 1017. The Culavamsa says that the capital at Anuradhapura was "utterly destroyed in every way by the Chola army.[44] The capital was at Polonnaruwa which was renamed "Jananathamangalam".[43]

A partial consolidation of Chola power in Rajarata had succeeded the initial season of plunder. With the intention to transform Chola encampments into more permanent military enclaves, Saivite temples were constructed in Polonnaruva and in the emporium of Mahatittha. Taxation was also instituted, especially on merchants and artisans by the Cholas.[45] In 1014 Rajaraja I died and was succeeded by his son the Rajendra Chola I, perhaps the most aggressive king of his line. Chola raids were launched southward from Rajarata into Rohana. By his fifth year, Rajendra claimed to have completely conquered the island. The whole of Anuradhapura including the south-eastern province of Rohana were incorporated into the Chola Empire.[46] As per the Sinhalese chronicle Mahavamsa, the conquest of Anuradhapura was completed in the 36th year of the reign of the Sinhalese monarch Mahinda V, i.e. about 1017–18.[46] But the south of the island, which lacked large an prosperous settlements to tempt long-term Chola occupation, was never really consolidated by the Chola. Thus, under Rajendra, Chola predatory expansion in Ceylon began to reach a point of diminishing returns.[45] According to the Culavamsa and Karandai plates, Rajendra Chola led a large army into Anuradhapura and captured Mahinda's crown, queen, daughter, vast amount of wealth and the king himself whom he took as a prisoner to India, where he eventually died in exile in 1029.[47][46]

The Chola conquest had one permanent result in that the capital of Anuradhapura was destroyed by the Cholas. Polonnaruwa, a military outpost of the Sinhalese kingdom,[48] was renamed Jananathamangalam, after a title assumed by Rajaraja I, and become the new center of administration for the Cholas. This was because earlier Tamil invaders had only aimed at overlordship of Rajarata in the north, but the Cholas were bent on control of the whole island. There is practically no trace of chola rule in Anuradhapura. When Sinhalese sovereignty was restored under Vijayabahu I, he crowned himself at Anuradhapura but continued to have his capital at Polonnaruwa for it being more central and made the task of controlling the turbulent provence of Rohana much easier.[43]

Government and military

Monarch

The kingdom was under the rule of a king. The consecration ceremonies and rituals associated with kingship began during the reign of Devanampiya Tissa,[49] under the influence of Ashoka of India.[50] The whole country was brought under the rule of a single monarch by Dutthagamani for the first time. Before this, it had several principalities independent of the Anuradhapura Kingdom.[49] The succession of the throne was patrilineal, or if that cannot be the case, inherited by the eldest brother of the previous king.[51] The king of Anuradhapura was seen as the supreme ruler throughout the island, even at times when he did not have absolute control over it.[52]

Four dynasties have ruled the kingdom from its founding to its ending. The rulers from Vijaya to Subharaja (60–67) are generally considered as the Vijayan dynasty.[N 3][53] Pandukabhaya was the first ruler of the Anuradhapura Kingdom belonging to this dynasty. The Vijayan dynasty existed until Vasabha of the Lambakanna clan seized power in 66 AD. His ascension to the throne saw the start of the first Lambakanna dynasty, which ruled the country for more than three centuries.[54] A new dynasty began with Dhatusena in 455. Named the Moriya dynasty, the origins of this line are uncertain although some historians trace them to Shakya princes who accompanied the sapling of the Sri Maha Bodhi to Sri Lanka.[55] The last dynasty of the Anuradhapura period, the second Lambakanna dynasty, started with Manavanna (684–718) seizing the throne in 684 and continued till the last ruler of Anuradhapura, Mahinda V.[56]

Officials

Royal officials were divided into three categories; officials attached to the palace, officials of central administration and officials of provincial administration. One of the most important positions was the purohita, the advisor of the king.[51] The king also had a board of ministers called amati paheja.[57] In central administration, senapati (Commander-in-Chief of the Army) was a position second only to the king, and held by a member of nobility.[58] This position, and also the positions of yuvaraja (sub king), administrative positions in the country's provinces and major ports and provinces, were often held by relatives of the king.[59]

The kingdom was often divided into sections or provinces and governed separately. Rajarata, the area around the capital, was under the direct administration of the king, while the Ruhuna (southern part of the country) and the Malaya Rata (hill country) were governed by officials called apa and mapa. These administrative units were further divided into smaller units called rata. Officials called ratiya or ratika were in charge of these.[N 4] The smallest administrative unit was the gama (village), under a village chief known as gamika or gamladda.[60]

Buddhist priesthood

A close link existed between the ruler and the Sangha (Buddhist priesthood) since the introduction of Buddhism to the country. This relationship was further strengthened during Dutthagamani's reign. The monks often advised and even guided the king on decisions. This association was initially with the Mahavihara sect, but by the middle of the 1st century BC, the Abhayagiri sect had also begun to have a close link to the ruling of the country. By the end of the 3rd century AD, the Jetavana sect had also become close to the ruler.[61] Estrangements between the ruler and the priesthood often weakened the government, as happened during the reign of Lanjatissa.[62] Even Valagamba's resistance movement was initially hampered because of a rift with the Mahavihara, and he succeeded only after a reconciliation was affected.[63] Some rulers patronized only one sect, but this often led to unrest in the country and most rulers equally supported all sects.[64] Despite this, religious establishments were often plundered during times of internal strife by the rulers themselves, such as during the reigns of Dathopatissa I (639–650) and Kashyapa II (650–659).[59]

Law

Customs, traditions and moral principles based on Buddhism were used as the bases of law. Specific laws were eventually developed and adopted. Samantapasadika, a 5th-century commentary, gives details of complex regulations on the theft of fish. The chief judicial officer was known as viniccayamacca and there were several judicial officers under him, known as vinicchayaka. Apart from them, village headmen and provincial governors were also given the power to issue judgments. The king was the final judge in legal disputes, and all cases against members of the royal family and high dignitaries of the state were judged by him. However, the king had to exercise this power with care and after consulting with his advisers.[65] Udaya I recorded judgments that were regarded as important precedents in the royal library in order to maintain uniformity in judicial decisions.[66]

Initially, the administration of justice at village level was the responsibility of village assemblies, which usually consisted of the elders of the village.[67] However, towards the end of the Anuradhapura Kingdom a group of ten villages, known as dasagam, was responsible for upholding justice in that area. The laws and legal measures to be followed by them were proclaimed by the king. Several rock inscriptions that record these proclamations have been found in archaeological excavations. Punishments differed from ruler to ruler. Some kings, such as Sanghabodhi (247–249) and Voharika Tissa (209–231) were lenient in this aspect, while rulers like Ilanaga (33–43) and Jettha Tissa I (263–273) were harsher. However, crimes such as treason, murder, and slaughter of cattle were generally punishable by death.[68]

Military

During the early stages, the Anuradhapura Kingdom did not have a strong regular army except for a small body of soldiers. These were assigned to guarding the capital and the royal palace. The King had the right to demand an able-bodied son for military service from every family in his kingdom. In times of war, a larger army was formed using this method. An army consisted of four main divisions; an elephant corps, cavalry, chariots and infantry.[69] This combination was called Chaturangani Sena (fourfold army). However, the majority of the army was infantry composed of swordsmen, spearmen and archers.[70][71]

When such an army was prepared, it was commanded by several generals. The Commander-in-Chief of the army was usually a member of nobility. The King and his generals led the army from the front during battles, mounted on elephants.[69] The major cities of the kingdom were defended with defensive walls and moats. Sieges, often lasting several months, were common during warfare. Single combat between the opposing kings or commanders, mounted on elephants, often decided the outcome of the battle.[72]

South Indian mercenaries were often employed in the armies of the Anuradhapura Kingdom during its latter stages.[69] Manavanna and Moggallana I (491–508) obtained the assistance of the Pallavas during succession disputes to secure the throne.[39] However, the Anuradhapura kingdom appears to have had strong armies during some periods, such as when Sena II sent his armies to South India against the Pandyan king.[73] Gajabahu I also launched an invasion against South India[N 5] to rescue 12,000 captives, and brought back 12,000 prisoners as well as the freed captives.[74] Surprisingly however, a navy was not considered important during the Anuradhapura Kingdom, and one was rarely maintained. This would have been the first line of defence for the island nation and would also have been helpful in dealing with invasions from South India.[72]

Trade and economy

The economy of the Anuradhapura Kingdom was based mainly on agriculture.[69] The main agricultural product was rice, the cultivation of which was supported by an intricate irrigation network. Rice cultivation began around the Malvatu Oya, Deduru Oya and Mahaweli Ganga and spread throughout the country.[75] Shifting cultivation was also done during the rainy seasons.[76] Rice was produced in two main seasons named Yala and Maha. Due to the extensive production of rice, the country was mostly self-sufficient.[77] Cotton was grown extensively to meet the requirements of cloth. Sugarcane and Sesame were also grown and there are frequent references in classical literature to these agricultural products. Finger millet was grown as a substitute for rice, particularly in the dry zone of the country.[78] Surpluses of these products, mainly rice, were exported.[79][80]

The primary goods exported during the Anuradhapura period are gemstones, spices, pearls and elephants, while ceramic ware, silks, perfumes and wines were imported from other countries.[81] The city of Anuradhapura itself became an important commercial center as the residence of many foreign merchants from around the world. From very early times was a settlement of Greeks known as Yavanas. Professor Merlin Peris, former Professor of Classics at the University of Peradeniya, writes that “The Greeks whom King Pandukabhaya settled in the West Gate of Anuradhapura were not second or third generation of Greeks who arrived in NW India but were men who, just two decades ago at the most, left Greek homelands as Alexander’s camp followers and come to Sri Lanka with or in the wake of Alexander’s troops. When their fellow Greeks showed reluctance to push further south, these Greeks apparently had done so.”[82]

By the fifth century one of Persians in addition to Tamil and Arab merchants.[83] These foreign merchants, mainly Arabs, often acted as middlemen in these imports and exports.[69] By the ninth century these Muslim traders had established themselves around the ports of the Anuradhapura Kingdom, they would soon form the still extant Muslim community of the island.[84] Luxury cloth was also imported from Eastern India and China.[78] A stone inscription in Anuradhapura implies that the market or bazaar was an important functionality in the city.[85] Trade was limited in villages since they were mostly self-sufficient, but essential commodities such as salt and metal had to be obtained from outside.[86] The country's position in the Indian Ocean and its natural bays made it a centre of international trade transit.[87] Ports such as Mahatittha (Mannar) and Gokanna (Trincomalee) were used as trading ports during the Anuradhapura Kingdom.[88]

Currency was often used for settling judicial fines, taxes and payments for goods[N 6] or services.[89] However, remuneration for services to the king, officials and temples were often made in the form of land revenue. The oldest coins found at Anuradhapura date up to 200 BC.[90] These earliest coins were punch marked rectangular pieces of silver known as kahavanu. These eventually became circular in shape, which were in turn followed by die struck coins.[91] Uncoined metals, particularly gold and silver, were used for trading as well.[92] Patterns of elephants, horses, swastika and Dharmacakra were commonly imprinted on the coins of this period.[93]

The primary tax of this period was named bojakapati (grain tax) and charged for land used for cultivation.[94] A water tax, named dakapati was also charged for the water used from reservoirs.[95] Customs duties were also imposed in ports.[96] Those unable to pay these taxes in cash were expected to take part in services such as repairing reservoirs. The administration of taxes was the duty of Badagarika, the king's treasurer.[97]

Culture

Culture in the Anuradhapura Kingdom was largely based on Buddhism with the slaughter of animals for food considered low and unclean. As a result, animal husbandry, except for the rearing of buffalo and cattle, was uncommon. Elephants and horses were prestige symbols, and could only be afforded by the nobility. The skills needed to train and care for these animals were highly regarded .[98] Cattle and buffalo were used for ploughing and preparing paddy fields.[99] Dairy products formed an important part of people's diets while Pali and Sinhala literature often refer to five products obtained from the cow: milk, curd, buttermilk, ghee and butter.[100] Bullocks and bullock carts were also used for transport.[101]

Metalwork was an important and well-developed craft, and metal tools such as axes, mammoties and hoes were widely used. Weapons and tools of iron and steel were produced in large scale for the military.[102] A good indication of the development of metalwork of this period is the Lovamahapaya, which had been roofed entirely with copper.[103]

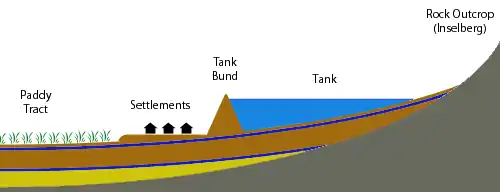

Villages were usually concentrated around irrigation reservoirs to enable easy access to water for agriculture. Houses stood immediately below the reservoir embankment, between the water and the paddy fields below. This facilitated easy control of the water supply to the fields and also supported maintenance of domestic gardens for fruit and vegetable production.[104] A village typically consisted of a cluster of dwellings, paddy fields, a reservoir, a grazing ground, shift crop reserves and a village forest. In areas of high rainfall, a perennial watercourse often took the place of the reservoir.[67] Inland fishing was widespread during the Anuradhapura Kingdom period because of the numerous reservoirs.[105] Although not entirely absent, sea fishing was not common during this period mainly because of the rudimentary nature of transporting sea fish to cities which were located far inland.[106]

Women appear to have enjoyed considerable freedom and independence during this period.[107] Dutthagamani frequently sought his mother's advice during his military campaign.[108] Rock inscriptions show that women donated caves and temples for the use of the sangha. However, there are no records of women holding any administrative posts. It is not clear if women were given equal footing with men, but they did have complete freedom in religious matters.[109]

Religion

.jpg.webp)

The religion of the ruling elite was Brahmanism until the introduction of Buddhism to Sri Lanka during the reign of Devanampiya Tissa. It spread rapidly throughout the country under his patronage becoming the official religion of the kingdom. Despite this status the tolerance of Buddhist society ensured the survival of Hinduism with only a minor loss of influence.[2][110] After this, the rulers were expected to be the protectors of Buddhism in the country and it became a legitimizing factor of royal authority.[111] Three fraternities of Buddhism had come into existence by the end of the Anuradhapura Kingdom; Mahavihara, Abhayagiri and Jetavana. Mahavihara was established immediately after the introduction of Buddhism to the country. Representing the Theravada teachings, it remained strictly conventional throughout the Anuradhapura Kingdom. The Abhayagiri fraternity, established after Abhayagiriya was built, represented several schools of Buddhist thought. It did not restrict itself to Theravada and accepted Mahayana and Tantric ideas as well. Little evidence exists on the Jetavana fraternity which was established after the Jetavanaramaya was built, later than the other two. However, it too was receptive to new and more liberal views regarding Buddhism.[112]

Rulers sponsored Theravada and often took steps to stop the spreading of Mahayana beliefs. Rulers such as Aggabodhi I, Kashyapa V (914–923) and Mahinda IV (956–972) promulgated disciplinary rules for the proper conduct of the Sangha.[59] Voharika Tissa and Gothabhaya (249–262) expelled several monks from the order for supporting such views.[113] A change in this occurred when Mahasena embraced Mahayana teachings and acted against Theravada institutions. However, he too accommodated Theravada teachings after the population rebelled against him.[114] As the kingdom and the authority or kings declined, Mahayana and Tantric doctrines again began to spread, however, Theravada remained the main and most widespread doctrine.[115]

Followers of Hinduism were also present to some extent during the Anuradhapura Kingdom. There were a number of them in Rajarata during Elara's reign. Mahasen destroyed several Hindu temples during his reign in the 2nd century. Particularly Indian merchant communities living near ports such as Mahatittha and Gokanna were followers of Hinduism and Hindu temples were constructed in these areas. By the end of the Anuradhapura Kingdom, large Hindu temples such as the Konesvaram temple had been constructed.[116] Historical sources[N 7] indicate that there were also Jains in Anuradhapura during the reign of Valagamba.[117]

Literature

From the 3rd century BC to the 3rd century AD, inscriptions are recorded in the Brāhmī script. This gradually developed into the modern sinhala script, but this was not complete by the end of the Anuradhapura Kingdom. The first reference in historical sources to any written work is about 80 BC, but both Sinhala and Pali literature existed even two centuries before this, if not earlier.[118] The oldest Sinhala literature is found at Sigiriya.[119] Poems written from the 6th century to the end of the Anuradhaura kingdom are found among the graffiti on the mirror wall at Sigiriya. Most of these verses are describing or even addressed to the female figures depicted in the frescoes of Sigiriya.[120] The majority of these poems have been written between the 8th and 10th centuries.[121]

Only three Sinhala books survive from the Anuradhapura period. One of them, Siyabaslakara, was written in the 9th or 10th century on the art of poetry and is based on the Sanskrit Kavyadarsha. Dampiya Atuva Gatapadaya is another, and is a glossary for the Pali Dhammapadatthakatha, providing Sinhala words and synonyms for Pali words. The third book is Mula Sikha Ha Sikhavalanda, a set of disciplinary rules for Buddhist monks. Both these have been written during the last two centuries of the Anuradhapura period.[122]

During the reign of Valagamba, the Pali Tripitaka was written in palm leaves.[123] Several commentaries on Buddhism, known as Atthakatha have also been written during the reign of Mahanama (406–428). Pali chronicles such as Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa have been written during the Anuradhapura Kingdom, and are still useful as resources for studying the history of the country.[124][125]

Art

The Sigiriya Frescoes found at Sigiriya, Sri Lanka were painted during the reign of King Kashyapa I (ruled 477 — 495 AD). Depicting female figures carrying flowers, they are the oldest surviving paintings of the Anuradhapura period.[126] Various theories exist as to who are shown in these paintings. Some suggest that they are apsaras (celestial nymphs),[127] others suggest that they are the ladies of the king's court or even a representation of lightning and rain clouds.[128] Although they bear some similarity to the paintings of Ajanta in India, there are significant differences in style and composition suggesting that these are examples of a distinctive Sri Lankan school of art.[129]

Paintings from a cave at Hindagala date back to the late Anuradhapura period, and may even belong to the same period as the Sigiriya paintings. The paintings of Sigiriya and Hindagala are the only surviving specimens of art of the Anuradhapura Kingdom. However, remnants of paintings indicate that walls and ceilings of some buildings and the inside walls of stupas and vahalkadas were also painted.[126] Saddhatissa had employed painters to decorate the Ruwanweli Seya when his brother Dutthagamani wanted to see it on his death bed.[130]

Statue making, most noticeably statues of the Buddha, was an art perfected by the Sri Lankan sculptors during the Anuradhapura Kingdom. The earliest Buddha statues belonging to the Anuradhapura period date back to the 1st century AD.[131] Standard postures such as Abhaya Mudra, Dhyana Mudra, Vitarka Mudra and Kataka Mudra were used when making these statues. The Samadhi statue in Anuradhapura, considered one of the finest examples of ancient Sri Lankan art,[132] shows the Buddha in a seated position in deep meditation, and is sculpted from dolomitic marble and is datable to the 4th century. The Toluvila statue is similar to this, and dates to the later stages of the Anuradhapura Kingdom. Notable standing Buddha statues dating from the Anuradhapura period include the ones at Avukana, Maligavila and Buduruvagala. The Buduruvagala statue is the tallest in the country, standing at 50 feet (15 m). All these statues are carved out of rock.[133]

The carvings at Isurumuniya are some of the best examples of the stone carving art of the Anuradhapura Kingdom. Skill in arts was a respected and valued trait during this period and artists were well rewarded by the rulers. The Mahavamsa records that Jettha Tissa II (328–337) was himself skilled in stone and ivory carving.[134]

Architecture and engineering

Architecture

The construction of stupas was noticeable not only during the Anuradhapura Kingdom but throughout the history of Sri Lanka. Stupas were built enshrining an object of worship. The stupa of Thuparamaya, built by Devanampiya Tissa, is one of the earliest built and was constructed immediately after the arrival of Buddhism. The construction of large stupas was begun by King Dutthagamani with the construction of the Ruwanweli Seya, standing 300 feet (91 m) high with a circumference of 298 feet (91 m).[135]

The Anuradhapura dagabas which date from the early centuries of the Anuradhapura period, are of such colossal proportions that they constitute the largest structures of their type anywhere in the Buddhist World, even rivaling the Pyramids of Egypt in size.[136]

The Abhayagiri stupa in the Abhayagiriya monastic complex is another large stupa of the Anuradhapura period the original height of which was 350 feet (110 m). The Jetavana stupa, constructed by Mahasen, is the largest in the country.[137] Stupas had deep and well constructed foundations, and the builders were clearly aware of the attributes of the materials used for construction. Suitable methods for each type of material have been used to lay foundations on a firm basis.[138]

All buildings have been adorned with elaborate carvings and sculptures and were supported by large stone columns. These stone columns can be seen in several buildings such as the Lovamahapaya (brazen palace).[139] Drainage systems of these buildings are also well planned, and terra cotta pipes were used to carry water to drainage pits. Large ponds were attached to some monasteries, such as the Kuttam Pokuna (twin pond). Hospital complexes have also been found close to monasteries. Buildings were constructed using timber, bricks and stones. Stones were used for foundations and columns, while brick were used for walls. Lime mortar was used for plastering walls.[140]

Irrigation and water management

Rainfall in the dry zone of Sri Lanka is limited to 50-75 inches. Under these conditions, rain fed cultivation was difficult, forcing early settlers to develop means to store water in order to maintain a constant supply of water for their cultivations. Small irrigation tanks were constructed at village level, to support the cultivations of that village.[141] The earliest medium-scale irrigation tank is the Basawakkulama reservoir built by King Pandukabhaya. Nuwara wewa and Tissa Wewa reservoirs were constructed a century later. These reservoirs were enlarged in subsequent years by various rulers.[142]

Construction of large scale reservoirs began in the 1st century AD under the direction of Vasabha. The Alahara canal, constructed by damming the Amban river to divert water to the west for 30 miles (48 km), was constructed during this period. Among the reservoirs constructed during the reign of Vasabha, Mahavilacchiya and Nocchipotana reservoirs both have circumferences of about 2 miles (3.2 km). During the reign of Mahasen, the Alahara canal was widened and lengthened to supply water to the newly constructed Minneriya tank, which covered 4,670 acres (18.9 km2) and had a 1.25 miles (2.01 km) long and 44 feet (13 m) high embankment. He was named Minneri Deiyo (god of Minneriya) for this construction and is still referred to as such by the people in that area.[143] The Kavudulu reservoir, Pabbatanta canal and Hurulu reservoir were among the large irrigation constructions carried out during this period. These constructions contributed immensely to the improvement of agriculture in the northern and eastern parts of the dry zone. Reservoirs were also constructed using tributaries of the Daduru Oya during this period, thereby supplying water to the south western part of the dry zone. This conservation and distribution of water resources ensured that the water supply was sufficient throughout the dry zone.[144] James Emerson Tennent[N 8] described the ancient irrigation network as:

... there seems every reason to believe that from their own subsequent experience and the prodigious extent to which they occupied themselves in the formulation of works of this kind, they attained a facility unsurpassed by the people of any other country.[145]

The water resources of the dry zone were further exploited during the times of Upatissa I and Dhatusena. The construction of the Kala wewa, covering an area of 6,380 acres (25.8 km2) with an embankment 3.75 miles (6.04 km) long and 40 feet (12 m) high, was done during Dhatusena's reign. A 54 miles (87 km) canal named the Jayaganga carries water from the Kala wewa to the Tissa Wewa and feeds a network of smaller canals. The construction of this network is also attributed to Dhatusena. The Jayaganga supplied water to 180 square kilometres of paddy fields.[144] By the end of the 5th century, two major irrigation networks, one supported by the Mahaweli river and the other by Malvatu Oya and Kala Oya, were covering the Rajarata area. The Mahavamsa records that many other rulers constructed a number of irrigation tanks, some of which have not yet been identified. By the 8th century, large tanks such as Padaviya, Naccaduva, Kantale and Giritale had come into existence, further expanding the irrigation network. However, from the 8th century to the end of the Anuradhapura Kingdom, there wasn't much activity in construction of irrigation works.[25]

Technology

Advanced technology was required for the planning and construction of large reservoirs and canals. When constructing reservoirs, the gaps between low ridges in the dry zone plains were used for damming water courses. Two different techniques were used in construction; one method involved making an embankment using natural rock formations across a valley and the other involved diverting water courses through constructed canals to reservoirs. All the reservoirs and canals in an area were interconnected by an intricate network, so that excess water from one will flow into the other.[146] The locations of these constructions indicate that the ancient engineers were aware of geological formations in the sites as well, and made effective use of them.[147] Underground conduits have also been constructed to supply water to and from artificial ponds, such as in the Kuttam Pokuna and the ponds at Sigiriya.[148][149]

The 54 miles (87 km) long Jayaganga has a gradient of six inches to the mile, which indicates that the builders had expert knowledge and accurate measuring devices to achieve the minimum gradient in the water flow. The construction of Bisokotuva, a cistern sluice used to control the outward flow of water in reservoirs, indicates a major advancement in irrigation technology. Since the 3rd century, these sluices, made of brick and stone, were placed at various levels in the embankments of reservoirs.[150][151]

Notes

- This flag, depicting the moon, sun and a lion bearing a sword, is believed to have been used as the royal standard of Dutthagamani, and subsequent rulers.[1]

- Buddhism was such an important factor in this period that Mendis (2000), p.196 asserts, "The island of Lanka belonged to the Buddha himself; it was like a treasury filled with the three gems".

- This is also known as the Anuradhapura dynasty, starting from Pandukabhaya.

- This position was called rataladda by the later period of the Anuradhapura Kingdom.

- This is disputed by some historians however, since there is no mention of this in the Mahavamsa although the Rajavaliya describes the event in detail.

- According to Samantapasadika, the use of coins in transactions involving the purchasing of items had become common by the 5th century.

- The term historical sources used in this article refer to the ancient texts on the history of Sri Lanka, mainly Mahavamsa and Dipavamsa and Rajavaliya.

- Sir James Emerson Tennent was the Colonial Secretary of Ceylon from 1845 to 1850. He has written several books on the country and its history.

References

Citations

- "Sri Lanka's National Flag". The Sunday Times. 3 February 2008. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- De Silva 2014, p. 58.

- "The downfall of the Anuradhapura kingdom and South Indian influences" (PDF). Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- Perera (2001), p.45

- Wijesooriya (2006), p. 20

- Blaze (1995), p. 19

- Yogasundaram (2008), p. 41

- Wijesooriya (2006), p. 27

- Bandaranayake (2007), p. 6

- Mendis (1999), p. 7

- Wijesooriya (2006), p. 28

- Siriweera (2004), p. 25

- Moratuwagama (1996), p. 225

- Siriweera (2004), p. 27

- Ludowyk (1985), p. 61

- Moratuwagama (1996), p. 252

- Moratuwagama (1996), p. 238

- Wijesooriya (2006), p. 75

- Siriweera (2004), p. 35

- Siriweera (2004), p. 36

- Wijesooriya (2006), p. 114

- Wijesooriya (2006), p. 81

- Wijesooriya (2006), p. 88

- Wijesooriya (2006), p. 93

- Siriweera (2004), p. 171

- Mendis (1999), p. 11

- Wijesooriya (2006), p. 34

- Wijesooriya (2006), p. 38

- Ludowyk (1985), p. 46

- Ludowyk (1985), p. 49

- Wijesooriya (2006), p. 41

- Ludowyk (1985), p. 55

- Blaze (1995), p. 58

- Wijesooriya (2006), p. 89

- Blaze (1995), p. 59

- Rambukwelle (1993), p. 51

- Wijesooriya (2006), p. 47

- Wijesooriya (2006), p. 49

- Siriweera (2004), p. 42

- Wijesooriya (2006), p. 108

- Wijesooriya (2006), p. 112

- Siriweera (2004), p. 44

- Sastri 1935, p. 172–173.

- Spencer 1976, p. 411.

- Spencer 1976, p. 416.

- Sastri 1935, p. 199–200.

- Spencer 1976, p. 417.

- as noted by its native name of Kandavura Nuvara (the camp city)

- Siriweera (2004), p. 86

- Wijesooriya (2006), p. 30

- Siriweera (2004), p. 87

- Perera (2001), p. 48

- Nicholas and Paranavitana (1961), p. 54

- Nicholas and Paranavitana (1961), p. 77

- Nicholas and Paranavitana (1961), p. 123

- Nicholas and Paranavitana (1961), p. 143

- Siriweera (2004), p. 90

- Siriweera (2004), p. 88

- Siriweera (1994), p. 8

- Siriweera (2004), p. 91

- Siriweera (1994), p. 6

- Rambukwelle (1993), p. 45

- Rambukwelle (1993), p. 46

- Siriweera (1994), p. 7

- Siriweera (2004), p. 92

- Mendis (1999), p. 144

- Rambukwelle (1993), p. 38

- Siriweera (2004), p. 93

- Yogasundaram (2008), p. 66

- Siriweera (2004), p. 89

- Ellawala (1969), p.148

- Yogasundaram (2008), p. 67

- Wijesooriya (2006), p. 110

- Mendis (1999), p. 57

- Siriweera (2004), p. 183

- Goonaratne and Hirashima (1990), p. 153

- Siriweera (2004), p. 190

- Siriweera (2004), p. 182

- Siriweera (2004), p. 192

- Seneviratna (1989), p. 54

- Siriweera (1994), p. 114

- Did Anuradhapura Greeks come east with Alexander?

- De Silva 2014, p. 46.

- De Silva 2014, p. 47.

- Siriweera (2004), p. 207

- Siriweera (2004), p. 212

- Siriweera (2004), p. 218

- Siriweera (2004), p. 228

- Siriweera (1994), p 120

- Siriweera (2004), p. 213

- Siriweera (2004), p. 214

- Siriweera (2004), p. 215

- Codrington (1994), p. 19

- Siriweera (1994), p. 167

- Siriweera (1994), p. 168

- Siriweera (1994), p. 169

- Siriweera (1994), p. 170

- Siriweera (2004), p. 200

- Siriweera (2004), p. 193

- Siriweera (2004), p. 194

- Siriweera (2004), p. 195

- Ellawala (1969), p. 151

- Ellawala (1969), p. 152

- Siriweera (2004), p. 187

- Siriweera (2004), p. 201

- Siriweera (1994), p. 39

- Ellawala (1969), p. 82

- Wettimuny, Samangie (17 August 2008). "Unsurpassed heroism: Women in Mahavamsa". Sunday Observer. Archived from the original on 3 August 2009. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- Ellawala (1969), p. 83

- Siriweera (2004), p. 244

- Siriweera (2004), p. 245

- Siriweera (2004), p. 248

- Siriweera (2004), p. 246

- Siriweera (2004), p. 247

- Siriweera (2004), p. 250

- Siriweera (2004), p. 254

- Mendis (1999), p. 104

- Ellawala (1969), p. 87

- Siriweera (2004), p. 267

- Lokubandara (2007), p. 37

- Lokubandara (2007), p. 29

- Siriweera (2004), p. 268

- Ellawala (1969), p. 86

- Siriweera (2004), p. 271

- Mendis (1999), p. 1

- Siriweera (2004), p. 290

- Bandaranayake (2007), p. 8

- Bandaranayake (2007), p. 11

- Bandaranayake (2007), p. 12

- Ellawala (1969), p. 153

- Siriweera (2004), p. 286

- "Sacred city of Anuradhapura". The Sunday Times. 9 December 2007. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- Siriweera (2004), p. 287

- Fernando (2001), p. 3

- Siriweera (2004), p. 283

- "Periodic Reporting Exercise on the Application of the World Heritage Convention" (PDF). UNESCO. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- Siriweera (2004), p. 284

- Basnayake (1986), p. 109

- Siriweera (2004), p. 280

- Siriweera (2004), p. 281

- Siriweera (2004), p. 168

- Siriweera (2004), p. 169

- Mendis (1999), p. 74

- Siriweera (2004), p. 170

- Mendis (2000), p. 248

- Siriweera (2004), p. 174

- Seneviratna (1989), p. 89

- "The beautiful twin ponds of Anuradhapura". Sunday Observer. 2 November 2008. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- Bandaranayake (2007), p. 15

- Siriweera (2004), p. 175

- Seneviratna (1989), p. 76

Bibliography

- De Silva, K. M. (2014). A history of Sri Lanka ([Revised.] ed.). Colombo: Vijitha Yapa Publications. ISBN 978-955-8095-92-8.

- Bandaranayake, Senake (2007). Sigiriya. Central Cultural Fund. ISBN 978-955-613-111-6.

- Basnayake, H. T. (1986). Sri Lankan Monastic Architecture. Sri Satguru Publications. ISBN 978-81-7030-009-0.

- Blaze, L. E (1995). The Story of Lanka. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-1074-3.

- Codrington, H.W. (1994). Ceylon Coins and Currency. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-0913-6.

- Ellawala, H. (1969). Social History of Early Ceylon. Department of Cultural Affairs.

- Fernando, G. S. (2001). සිංහල සැරසිලි—Sinhala Sarasili [Sinhala Decorational Art] (in Sinhala). M. D. Gunasena and Company. ISBN 978-955-21-0525-8.

- Gooneratne, W.; Hirashima, S. (1990). Irrigation and Water Management in Asia. Sterling Publishers.

- Lokubandara, W. J. M. (2007). The Mistique of Sigiriya — Whispers of the Mirror Wall. Godage International Publishers. ISBN 978-955-30-0610-3.

- Ludowyk, E. F. C. (1985). The Story of Ceylon. Navrang Booksellers & Publishers. ISBN 978-81-7013-020-8.

- Mendis, Ranjan Chinthaka (1999). The Story of Anuradhapura. Lakshmi Mendis. ISBN 978-955-96704-0-7.

- Mendis, Vernon L. B. (2000). The Rulers of Sri Lanka. S. Godage & Brothers. ISBN 978-955-20-4847-0.

- Moratuwagama, H. M. (1996). සිංහල ථුපවංසය—Sinhala Thupavansaya [Sinhala Thupavamsa] (in Sinhala). Rathna Publishers. ISBN 978-955-569-068-3.

- Nicholas, C. W.; Paranavitana, S. (1961). A Concise History of Ceylon. Colombo University Press.

- Perera, Lakshman S. (2001). The Institutions of Ancient Ceylon from Inscriptions. 1. International Centre for Ethnic Studies. ISBN 978-955-580-055-6.

- Rambukwelle, P. B. (1993). Commentary on Sinhala Kingship — Vijaya to Kalinga Magha. Sridevi Printers. ISBN 978-955-95565-0-3.

- Sastri, K. A (2000) [1935]. The CōĻas. Madras: University of Madras.

- Seneviratna, Anuradha (1989). The Springs of Sinhala Civilization. Navrang Booksellers & Publishers. LCCN 89906331. OCLC 21524601.

- Siriweera, W. I. (2004). History of Sri Lanka. Dayawansa Jayakodi & Company. ISBN 978-955-551-257-2.

- Siriweera, W. I. (1994). A Study of the Economic History of Pre Modern Sri Lanka. Vikas Publishing House. ISBN 978-0-7069-7621-2.

- Wijesooriya, S. (2006). A Concise Sinhala Mahavamsa. Participatory Development Forum. ISBN 978-955-9140-31-3.

- Yogasundaram, Nath (2008). A Comprehensive History of Sri Lanka. Vijitha Yapa Publishers. ISBN 978-955-665-002-0.

- Spencer, George W. (May 1976). "The Politics of Plunder:The Cholas in Eleventh-Century Ceylon". The Journal of Asian Studies. 35 (3): 405–419. doi:10.2307/2053272. JSTOR 2053272.