Arabian horse

The Arabian or Arab horse (Arabic: الحصان العربي [ ħisˤaːn ʕarabiː], DMG ḥiṣān ʿarabī) is a breed of horse that originated on the Arabian Peninsula. With a distinctive head shape and high tail carriage, the Arabian is one of the most easily recognizable horse breeds in the world. It is also one of the oldest breeds, with archaeological evidence of horses in the Middle East that resemble modern Arabians dating back 4,500 years. Throughout history, Arabian horses have spread around the world by both war and trade, used to improve other breeds by adding speed, refinement, endurance, and strong bone. Today, Arabian bloodlines are found in almost every modern breed of riding horse.

An Arabian mare | |

| Other names | Arabian, Arab |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | Developed in the Middle East, most notably Arabian peninsula |

| Traits | |

| Weight |

|

| Height |

|

| Color | Bay, black, chestnut, or gray. Occasional dominant white, sabino, or rabicano patterns. |

| Distinguishing features | Finely chiseled bone structure, concave profile, arched neck, comparatively level croup, high-carried tail. |

| Breed standards | |

The Arabian developed in a desert climate and was prized by the nomadic Bedouin people, often being brought inside the family tent for shelter and protection from theft. Selective breeding for traits, including an ability to form a cooperative relationship with humans, created a horse breed that is good-natured, quick to learn, and willing to please. The Arabian also developed the high spirit and alertness needed in a horse used for raiding and war. This combination of willingness and sensitivity requires modern Arabian horse owners to handle their horses with competence and respect.

The Arabian is a versatile breed. Arabians dominate the discipline of endurance riding, and compete today in many other fields of equestrian sport. They are one of the top ten most popular horse breeds in the world. They are now found worldwide, including the United States and Canada, United Kingdom, Australia, continental Europe, South America (especially Brazil), and their land of origin, the Middle East.

Breed characteristics

Arabian horses have refined, wedge-shaped heads, a broad forehead, large eyes, large nostrils, and small muzzles. Most display a distinctive concave, or "dished" profile. Many Arabians also have a slight forehead bulge between their eyes, called the jibbah by the Bedouin, that adds additional sinus capacity, believed to have helped the Arabian horse in its native dry desert climate.[1][2] Another breed characteristic is an arched neck with a large, well-set windpipe set on a refined, clean throatlatch. This structure of the poll and throatlatch was called the mitbah or mitbeh by the Bedouin. In the ideal Arabian it is long, allowing flexibility in the bridle and room for the windpipe.[2]

Other distinctive features are a relatively long, level croup, or top of the hindquarters, and naturally high tail carriage. The USEF breed standard requires Arabians have solid bone and standard correct equine conformation.[3] Well-bred Arabians have a deep, well-angled hip and well laid-back shoulder.[4] Within the breed, there are variations. Some individuals have wider, more powerfully muscled hindquarters suitable for intense bursts of activity in events such as reining, while others have longer, leaner muscling better suited for long stretches of flat work such as endurance riding or horse racing.[5] Most have a compact body with a short back.[2] Arabians usually have dense, strong bone, and good hoof walls. They are especially noted for their endurance,[6][7] and the superiority of the breed in Endurance riding competition demonstrates that well-bred Arabians are strong, sound horses with superior stamina. At international FEI-sponsored endurance events, Arabians and half-Arabians are the dominant performers in distance competition.[8]

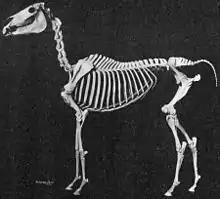

Skeletal analysis

Some Arabians, though not all, have 5 lumbar vertebrae instead of the usual 6, and 17 pairs of ribs rather than 18.[9] A quality Arabian has both a relatively horizontal croup and a properly angled pelvis as well as good croup length and depth to the hip (determined by the length of the pelvis), that allows agility and impulsion.[4][10] A misconception confuses the topline of the croup with the angle of the "hip" (the pelvis or ilium), leading some to assert that Arabians have a flat pelvis angle and cannot use their hindquarters properly. However, the croup is formed by the sacral vertebrae. The hip angle is determined by the attachment of the ilium to the spine, the structure and length of the femur, and other aspects of hindquarter anatomy, which is not correlated to the topline of the sacrum. Thus, the Arabian has conformation typical of other horse breeds built for speed and distance, such as the Thoroughbred, where the angle of the ilium is more oblique than that of the croup.[11][12][13] Thus, the hip angle is not necessarily correlated to the topline of the croup. Horses bred to gallop need a good length of croup and good length of hip for proper attachment of muscles, and so unlike angle, length of hip and croup do go together as a rule.[12]

Size

The breed standard stated by the United States Equestrian Federation, describes Arabians as standing between 14.1 to 15.1 hands (57 to 61 inches, 145 to 155 cm) tall, "with the occasional individual over or under".[3] Thus, all Arabians, regardless of height, are classified as "horses", even though 14.2 hands (58 inches, 147 cm) is the traditional cutoff height between a horse and a pony.[14] A common myth is that Arabians are not strong because they are relatively small and refined. However, the Arabian horse is noted for a greater density of bone than other breeds, short cannons, sound feet, and a broad, short back,[2] all of which give the breed physical strength comparable to many taller animals.[15] Thus, even a smaller Arabian can carry a heavy rider. For tasks where the sheer weight of the horse matters, such as farm work done by a draft horse,[16] any lighter-weight horse is at a disadvantage.[16] However, for most purposes, the Arabian is a strong and hardy light horse breed able to carry any type of rider in most equestrian pursuits.[15]

Temperament

For centuries, Arabian horses lived in the desert in close association with humans.[17] For shelter and protection from theft, prized war mares were sometimes kept in their owner's tent, close to children and everyday family life.[18] Only horses with a naturally good disposition were allowed to reproduce, with the result that Arabians today have a good temperament that, among other examples, makes them one of the few breeds where the United States Equestrian Federation rules allow children to exhibit stallions in nearly all show ring classes, including those limited to riders under 18.[19]

On the other hand, the Arabian is also classified as a "hot-blooded" breed, a category that includes other refined, spirited horses bred for speed, such as the Akhal-Teke, the Barb, and the Thoroughbred. Like other hot-bloods, Arabians' sensitivity and intelligence enable quick learning and greater communication with their riders; however, their intelligence also allows them to learn bad habits as quickly as good ones,[20] and they do not tolerate inept or abusive training practices.[21] Some sources claim that it is more difficult to train a "hot-blooded" horse.[22] Though most Arabians have a natural tendency to cooperate with humans, when treated badly, like any horse, they can become excessively nervous or anxious, but seldom become vicious unless seriously spoiled or subjected to extreme abuse.[21] At the other end of the spectrum, romantic myths are sometimes told about Arabian horses that give them near-divine characteristics.[23]

Colors

The Arabian Horse Association registers purebred horses with the coat colors bay, gray, chestnut, black, and roan.[24] Bay, gray and chestnut are the most common; black is less common.[25] The classic roan gene does not appear to exist in Arabians;[26] rather, Arabians registered by breeders as "roan" are usually expressing rabicano or, sometimes, sabino patterns with roan features.[27] All Arabians, no matter their coat color, have black skin, except under white markings. Black skin provided protection from the intense desert sun.[28]

Gray and white

Although many Arabians appear to have a "white" hair coat, they are not genetically "white". This color is usually created by the natural action of the gray gene, and virtually all white-looking Arabians are actually grays.[29] A specialized colorization seen in some older gray Arabians is the so-called "bloody-shoulder", which is a particular type of "flea-bitten" gray with localized aggregations of pigment on the shoulder.[30][31]

There are a very few Arabians registered as "white" having a white coat, pink skin and dark eyes from birth. These animals are believed to manifest a new form of dominant white, a result of a nonsense mutation in DNA tracing to a single stallion foaled in 1996.[32] This horse was originally thought to be a sabino, but actually was found to have a new form of dominant white mutation, now labeled W3.[32] It is possible that white mutations have occurred in Arabians in the past or that mutations other than W3 exist but have not been verified by genetic testing.[27]

Sabino

One spotting pattern, sabino, does exist in purebred Arabians. Sabino coloring is characterized by white markings such as "high white" above the knees and hocks, irregular spotting on the legs, belly and face, white markings that extend beyond the eyes or under the chin and jaw, and sometimes lacy or roaned edges.[33]

The genetic mechanism that produces sabino patterning in Arabians is undetermined, and more than one gene may be involved.[27] Studies at the University of California, Davis indicate that Arabians do not appear to carry the autosomal dominant gene "SB1" or sabino 1, that often produces bold spotting and some completely white horses in other breeds. The inheritance patterns observed in sabino-like Arabians also do not follow the same mode of inheritance as sabino 1.[34][35]

Rabicano or roan?

There are very few Arabians registered as roan, and according to researcher D. Phillip Sponenberg, roaning in purebred Arabians is actually the action of rabicano genetics.[26] Unlike a genetic roan, rabicano is a partial roan-like pattern; the horse does not have intermingled white and solid hairs over the entire body, only on the midsection and flanks, the head and legs are solid-colored.[26] Some people also confuse a young gray horse with a roan because of the intermixed hair colors common to both. However, a roan does not consistently lighten with age, while a gray does.[36][37]

Colors that do not exist in purebreds

There is pictorial evidence from pottery and tombs in Ancient Egypt suggesting that spotting patterns may have existed on ancestral Arabian-type horses in antiquity.[38] Nonetheless, purebred Arabians today do not carry genes for pinto or Leopard complex ("Appaloosa") spotting patterns, except for sabino.

Spotting or excess white was believed by many breeders to be a mark of impurity until DNA testing for verification of parentage became standard. For a time, horses with belly spots and other white markings deemed excessive were discouraged from registration and excess white was sometimes penalized in the show ring.[27]

Purebred Arabians never carry dilution genes.[39] Therefore, purebreds cannot be colors such as dun, cremello, palomino or buckskin.[40]

To produce horses with some Arabian characteristics but coat colors not found in purebreds, they have to be crossbred with other breeds.[41] Though the purebred Arabian produces a limited range of potential colors, they do not appear to carry any color-based lethal disorders such as the frame overo gene ("O") that can produce lethal white syndrome (LWS). Because purebred Arabians cannot produce LWS foals, Arabian mares were used as a non-affected population in some of the studies seeking the gene that caused the condition in other breeds.[42] Nonetheless, partbred Arabian offspring can, in some cases, carry these genes if the non-Arabian parent was a carrier.[43]

Genetic disorders

There are six known genetic disorders in Arabian horses. Two are inevitably fatal, two are not inherently fatal but are disabling and usually result in euthanasia of the affected animal; the remaining conditions can usually be treated. Three are thought to be autosomal recessive conditions, which means that the flawed gene is not sex-linked and has to come from both parents for an affected foal to be born; the others currently lack sufficient research data to determine the precise mode of inheritance.[44] Arabians are not the only breed of horse to have problems with inherited diseases; fatal or disabling genetic conditions also exist in many other breeds, including the American Quarter Horse, American Paint Horse, American Saddlebred, Appaloosa, Miniature horse, and Belgian.[44]

Genetic diseases that can occur in purebred Arabians, or in partbreds with Arabian ancestry in both parents, are the following:

- Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID). Recessive disorder, fatal when homozygous, carriers (heterozygotes) show no signs. Similar to the "bubble boy" condition in humans, an affected foal is born with a complete lack of an immune system, and thus generally dies of an opportunistic infection, usually before the age of three months.[45] There is a DNA test that can detect healthy horses who are carriers of the gene causing SCID, thus testing and careful, planned matings can now eliminate the possibility of an affected foal ever being born.[46]

- Lavender Foal Syndrome (LFS), also called Coat Color Dilution Lethal (CCDL). Recessive disorder, fatal when homozygous, carriers show no signs. The condition has its name because most affected foals are born with a coat color dilution that lightens the tips of the coat hairs, or even the entire hair shaft. Foals with LFS are unable to stand at birth, often have seizures, and are usually euthanized within a few days of birth.[47][48] In November 2009, Cornell University announced that a DNA test has been developed to detect carriers of LFS. Simultaneously, the University of Pretoria also announced that they had also developed a DNA test.[49]

- Cerebellar abiotrophy (CA or CCA). Recessive disorder, homozygous horses are affected, carriers show no signs. An affected foal is usually born without clinical signs, but at some stage, usually after six weeks of age, develops severe incoordination, a head tremor, wide-legged stance and other symptoms related to the death of the purkinje cells in the cerebellum. Such foals are frequently diagnosed only after they have crashed into a fence or fallen over backwards, and often are misdiagnosed as suffering from a head injury caused by an accident. Severity varies, with some foals having fast onset of severe coordination problems, others showing milder signs. Mildly affected horses can live a full lifespan, but most are euthanized before adulthood because they are so accident-prone as to be dangerous. As of 2008, there is a genetic test that uses DNA markers associated with CA to detect both carriers and affected animals.[50] Clinical signs are distinguishable from other neurological conditions, and a diagnosis of CA can be verified by examining the brain after euthanasia.[51]

- Occipital Atlanto-Axial Malformation (OAAM). This is a condition where the occiput, atlas and axis vertebrae in the neck and at the base of the skull are fused or malformed. Symptoms range from mild incoordination to the paralysis of both front and rear legs. Some affected foals cannot stand to nurse, in others the symptoms may not be seen for several weeks. This is the only cervical spinal cord disease seen in horses less than 1 month of age, and a radiograph can diagnose the condition. There is now a genetic test for OAAM.[52][53]

- Equine juvenile epilepsy, or Juvenile Idiopathic Epilepsy, sometimes referred to as "benign" epilepsy, is not usually fatal. Foals appear normal between epileptic seizures, and seizures usually stop occurring between 12 and 18 months.[48] Affected foals may show signs of epilepsy anywhere from two days to six months from birth.[54] Seizures can be treated with traditional anti-seizure medications, which may reduce their severity.[55] Though the condition has been studied since 1985 at the University of California, Davis, the genetic mode of inheritance is unclear, though the cases studied were all of one general bloodline group.[54] Recent research updates suggest that a dominant mode of inheritance is involved in transmission of this trait.[56] One researcher hypothesized that epilepsy may be linked in some fashion to Lavender Foal Syndrome due to the fact that it occurs in similar bloodlines and some horses have produced foals with both conditions.[48]

- Guttural Pouch Tympany (GPT) occurs in horses ranging from birth to 1 year of age and is more common in fillies than in colts. It is thought to be genetic in Arabians, possibly polygenic in inheritance, but more study is needed.[57] Foals are born with a defect that causes the pharyngeal opening of the eustachian tube to act like a one-way valve – air can get in, but it cannot get out. The affected guttural pouch is distended with air and forms a characteristic nonpainful swelling. Breathing is noisy in severely affected animals.[58] Diagnosis is based on clinical signs and radiographic examination of the skull. Medical management with NSAID and antimicrobial therapy can treat upper respiratory tract inflammation. Surgical intervention is needed to correct the malformation of the guttural pouch opening, to provide a route for air in the abnormal guttural pouch to pass to the normal side and be expelled into the pharynx. Foals that are successfully treated may grow up to have fully useful lives.[59]

The Arabian Horse Association in the United States has created a foundation that supports research efforts to uncover the roots of genetic diseases.[60] The organization F.O.A.L. (Fight Off Arabian Lethals) is a clearinghouse for information on these conditions.[61] Additional information is available from the World Arabian Horse Association (WAHO).[62]

Recent trends in halter breeding have given rise to Arabian horses with extremely concave features, raising concerns that the trait is detrimental to the animal's welfare.[63] Comparisons have been made to a similar trend with some dog breeds, where show judging awarding certain features has led to breeders seeking an ever more exaggerated form, with little concern as to the inherent function of the animal. Some veterinarians speculate that an extremely concave face is detrimental to a horse's breathing, but the issue has not been formally studied.[64]

Legends

Arabian horses are the topic of many myths and legends. One origin story tells how Muhammad chose his foundation mares by a test of their courage and loyalty. While there are several variants on the tale, a common version states that after a long journey through the desert, Muhammad turned his herd of horses loose to race to an oasis for a desperately needed drink of water. Before the herd reached the water, Muhammad called for the horses to return to him. Only five mares responded. Because they faithfully returned to their master, though desperate with thirst, these mares became his favorites and were called Al Khamsa, meaning, the five. These mares became the legendary founders of the five "strains" of the Arabian horse.[65][66] Although the Al Khamsa are generally considered fictional horses of legend,[67] some breeders today claim the modern Bedouin Arabian actually descended from these mares.[68]

Another origin tale claims that King Solomon was given a pure Arabian-type mare named Safanad ("the pure") by the Queen of Sheba.[67] A different version says that Solomon gave a stallion, Zad el-Raheb or Zad-el-Rakib ("Gift to the Rider"), to the Banu Azd people when they came to pay tribute to the king. This legendary stallion was said to be faster than the zebra and the gazelle, and every hunt with him was successful, thus when he was put to stud, he became a founding sire of legend.[69]

Yet another creation myth puts the origin of the Arabian in the time of Ishmael, the son of Abraham.[70] In this story, the Angel Jibril (also known as Gabriel) descended from Heaven and awakened Ishmael with a "wind-spout" that whirled toward him. The Angel then commanded the thundercloud to stop scattering dust and rain, and so it gathered itself into a prancing, handsome creature - a horse - that seemed to swallow up the ground. Hence, the Bedouins bestowed the title "Drinker of the Wind" to the first Arabian horse.[71]

Finally, a Bedouin story states that Allah created the Arabian horse from the south wind and exclaimed, "I create thee, Oh Arabian. To thy forelock, I bind Victory in battle. On thy back, I set a rich spoil and a Treasure in thy loins. I establish thee as one of the Glories of the Earth... I give thee flight without wings."[72] Other versions of the story claim Allah said to the South Wind: "I want to make a creature out of you. Condense." Then from the material condensed from the wind, he made a kamayt-colored animal (a bay or burnt chestnut) and said: "I call you Horse; I make you Arabian and I give you the chestnut color of the ant; I have hung happiness from the forelock which hangs between your eyes; you shall be the Lord of the other animals. Men shall follow you wherever you go; you shall be as good for flight as for pursuit; you shall fly without wings; riches shall be on your back and fortune shall come through your meditation."[73]

Origins

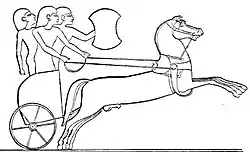

Arabians are one of the oldest human-developed horse breeds in the world.[23] The progenitor stock, the Oriental subtype or "Proto-Arabian" was believed to be a horse with oriental characteristics similar to the modern Arabian. Horses with these features appeared in rock paintings and inscriptions in the Arabian Peninsula dating back 3500 years.[74] In ancient history throughout the Ancient Near East, horses with refined heads and high-carried tails were depicted in artwork, particularly that of Ancient Egypt in the 16th century BC.[75]

Some scholars of the Arabian horse once theorized that the Arabian came from a separate subspecies of horse,[76] known as equus caballus pumpelli.[77] Other scholars, including Gladys Brown Edwards, a noted Arabian researcher, believe that the "dry" oriental horses of the desert, from which the modern Arabian developed, were more likely Equus ferus caballus with specific landrace characteristics based on the environments in which they lived, rather than being a separate subspecies.[9][77] Horses with similar, though not identical, physical characteristics include the Marwari horse of India, the Barb of North Africa, the Akhal-Teke of western Asia and the now-extinct Turkoman Horse.[77] Recent genetic studies of mitochondrial DNA in Arabian horses of Polish and American breeding suggest that the modern breed has heterogeneous origins with ten haplogroups. The modern concept of breed purity in the modern population cannot be traced beyond 200 years.[78]

Desert roots

There are different theories about where the ancestors of the Arabian originally lived. Most evidence suggests the proto-Arabian came from the area along the northern edge of the Fertile Crescent.[77] Another hypothesis suggests the southwestern corner of the Arabian peninsula, in modern-day Yemen, where three now-dry riverbeds indicate good natural pastures existed long ago, perhaps as far back as the Ice Age.[79][80] This hypothesis has gained renewed attention following a 2010 discovery of artifacts dated between 6590 and 7250 BCE in Al-Magar, in southwestern Saudi Arabia, that appeared to portray horses.[81]

The proto-Arabian horse may have been domesticated by the people of the Arabian peninsula known today as the Bedouin, some time after they learned to use the camel, approximately 4,000–5,000 years ago.[80][82] One theory is that this development occurred in the Nejd plateau in central Arabia.[74] Other scholars, noting that horses were common in the Fertile Crescent but rare in the Arabian peninsula prior to the rise of Islam, theorize that the breed as it is known today only developed in large numbers when the conversion of the Persians to Islam in the 7th century brought knowledge of horse breeding and horsemanship to the Bedouin.[83] The oldest depictions in the Arabian Peninsula of horses that are clearly domesticated date no earlier than 1800-2000 BCE.[81]

Regardless of origin, climate and culture ultimately created the Arabian. The desert environment required a domesticated horse to cooperate with humans to survive; humans were the only providers of food and water in certain areas, and even hardy Arabian horses needed far more water than camels in order to survive (most horses can only live about 72 hours without water). Where there was no pasture or water, the Bedouin fed their horses dates and camel's milk.[84] The desert horse needed the ability to thrive on very little food, and to have anatomical traits to compensate for life in a dry climate with wide temperature extremes from day to night. Weak individuals were weeded out of the breeding pool, and the animals that remained were also honed by centuries of human warfare.[85]

The Bedouin way of life depended on camels and horses: Arabians were bred to be war horses with speed, endurance, soundness, and intelligence.[85][86] Because many raids required stealth, mares were preferred over stallions as they were quieter, and therefore would not give away the position of the fighters.[85] A good disposition was also critical; prized war mares were often brought inside family tents to prevent theft and for protection from weather and predators.[87] Though appearance was not necessarily a survival factor, the Bedouin bred for refinement and beauty in their horses as well as for more practical features.[86]

Strains and pedigrees

For centuries, the Bedouin tracked the ancestry of each horse through an oral tradition. Horses of the purest blood were known as Asil and crossbreeding with non-Asil horses was forbidden. Mares were the most valued, both for riding and breeding, and pedigree families were traced through the female line. The Bedouin did not believe in gelding male horses, and considered stallions too intractable to be good war horses, thus they kept very few colts, selling most, and culling those of poor quality.[88]

Over time, the Bedouin developed several sub-types or strains of Arabian horse, each with unique characteristics,[89] and traced through the maternal line only.[90] According to the Arabian Horse Association, the five primary strains were known as the Keheilan, Seglawi, Abeyan, Hamdani and Hadban.[91] Carl Raswan, a promoter and writer about Arabian horses from the middle of the 20th century, held the belief that there were only three strains, Kehilan, Seglawi and Muniqi. Raswan felt that these strains represented body "types" of the breed, with the Kehilan being "masculine", the Seglawi being "feminine" and the Muniqi being "speedy".[92] There were also lesser strains, sub-strains, and regional variations in strain names.[93][94] Therefore, many Arabian horses were not only Asil, of pure blood, but also bred to be pure in strain, with crossbreeding between strains discouraged, though not forbidden, by some tribes. Purity of bloodline was very important to the Bedouin, and they also believed in telegony, believing if a mare was ever bred to a stallion of "impure" blood, the mare herself and all future offspring would be "contaminated" by the stallion and hence no longer Asil.[95]

This complex web of bloodline and strain was an integral part of Bedouin culture; they not only knew the pedigrees and history of their best war mares in detail, but also carefully tracked the breeding of their camels, Saluki dogs, and their own family or tribal history.[96] Eventually, written records began to be kept; the first written pedigrees in the Middle East that specifically used the term "Arabian" date to 1330 AD.[97] As important as strain was to the Bedouin, modern studies of mitochondrial DNA suggest that Arabian horses alive today with records stating descent from a given strain may not actually share a common maternal ancestry.[98]

Historic development

Role in the ancient world

Fiery war horses with dished faces and high-carried tails were popular artistic subjects in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, often depicted pulling chariots in war or for hunting. Horses with oriental characteristics appear in later artwork as far north as that of Ancient Greece and the Roman Empire. While this type of horse was not called an "Arabian" in the Ancient Near East until later,[99] these proto-Arabians shared many characteristics with the modern Arabian, including speed, endurance, and refinement. For example, a horse skeleton unearthed in the Sinai peninsula, dated to 1700 BC and probably brought by the Hyksos invaders, is considered the earliest physical evidence of the horse in Ancient Egypt. This horse had a wedge-shaped head, large eye sockets and small muzzle, all characteristics of the Arabian horse.[100]

In Islamic history

Following the Hijra in AD 622 (also sometimes spelled Hegira), the Arabian horse spread across the known world of the time, and became recognized as a distinct, named breed.[101] It played a significant role in the History of the Middle East and of Islam. By 630, Muslim influence expanded across the Middle East and North Africa, by 711 Muslim warriors had reached Spain, and they controlled most of the Iberian Peninsula by 720. Their war horses were of various oriental types, including both Arabians and the Barb horse of North Africa.[102]

Arabian horses also spread to the rest of the world via the Ottoman Empire, which rose in 1299. Though it never fully dominated the heart of the Arabian Peninsula, this Turkish empire obtained many Arabian horses through trade, diplomacy and war.[103] The Ottomans encouraged formation of private stud farms in order to ensure a supply of cavalry horses,[104] and Ottoman nobles, such as Muhammad Ali of Egypt also collected pure, desert-bred Arabian horses.[103]

El Naseri, or Al-Nasir Muhammad, Sultan of Egypt (1290–1342) imported and bred numerous Arabians in Egypt. A stud farm record was made of his purchases describing many of the horses as well as their abilities, and was deposited in his library, becoming a source for later study.[103][105] Through the Ottomans, Arabian horses were often sold, traded, or given as diplomatic gifts to Europeans and, later, to Americans.[80]

Egypt

Historically, Egyptian breeders imported horses bred in the deserts of Palestine and the Arabian peninsula as the source of their foundation bloodstock.[106] By the time that the Ottoman Empire dominated Egypt, the political elites of the region still recognized the need for quality bloodstock for both war and for horse racing, and some continued to return to the deserts to obtain pure-blooded Arabians. One of the most famous was Muhammad Ali of Egypt, also known as Muhammad Ali Pasha, who established an extensive stud farm in the 19th century.[107][108] After his death, some of his stock was bred on by Abbas I of Egypt, also known as Abbas Pasha. However, after Abbas Pasha was assassinated in 1854, his heir, El Hami Pasha, sold most of his horses, often for crossbreeding, and gave away many others as diplomatic gifts.[107][108][109] A remnant of the herd was obtained by Ali Pasha Sherif, who then went back to the desert to bring in new bloodstock. At its peak, the stud of Ali Pasha Sherif had over 400 purebred Arabians.[108][110] Unfortunately, an epidemic of African horse sickness in the 1870s that killed thousands of horses throughout Egypt decimated much of his herd, wiping out several irreplaceable bloodlines.[108] Late in his life, he sold several horses to Wilfred and Lady Anne Blunt, who exported them to Crabbet Park Stud in England. After his death, Lady Anne was also able to gather many remaining horses at her Sheykh Obeyd stud.[111]

Meanwhile, the passion brought by the Blunts to saving the pure horse of the desert helped Egyptian horse breeders to convince their government of the need to preserve the best of their own remaining pure Arabian bloodstock that descended from the horses collected over the previous century by Muhammad Ali Pasha, Abbas Pasha and Ali Pasha Sherif.[112] The government of Egypt formed the Royal Agricultural Society (RAS) in 1908,[113] which is known today as the Egyptian Agricultural Organization (EAO).[114] RAS representatives traveled to England during the 1920s and purchased eighteen descendants of the original Blunt exports from Lady Wentworth at Crabbet Park, and brought them to Egypt in order to restore bloodlines had been lost.[113] Other than several horses purchased by Henry Babson for importation to the United States in the 1930s,[115] and one other small group exported to the US in 1947, relatively few Egyptian-bred Arabian horses were exported until the overthrow of King Farouk I in 1952.[116] Many of the private stud farms of the princes were then confiscated and the animals taken over by the EAO.[114] In the 1960s and 1970s, as oil development brought more foreign investors to Egypt, some of whom were horse fanciers, Arabians were exported to Germany and to the United States, as well as to the former Soviet Union.[117][118] Today, the designation "Straight Egyptian" or "Egyptian Arabian" is popular with some Arabian breeders, and the modern Egyptian-bred Arabian is an outcross used to add refinement in some breeding programs.[112]

Arrival in Europe

Probably the earliest horses with Arabian bloodlines to enter Europe came indirectly, through Spain and France. Others would have arrived with returning Crusaders[103]—beginning in 1095, European armies invaded Palestine and many knights returned home with Arabian horses as spoils of war. Later, as knights and the heavy, armored war horses who carried them became obsolete, Arabian horses and their descendants were used to develop faster, agile light cavalry horses that were used in warfare into the 20th century.[80]

Another major infusion of Arabian horses into Europe occurred when the Ottoman Turks sent 300,000 horsemen into Hungary in 1522, many of whom were mounted on pure-blooded Arabians, captured during raids into Arabia. By 1529, the Ottomans reached Vienna, where they were stopped by the Polish and Hungarian armies, who captured these horses from the defeated Ottoman cavalry. Some of these animals provided foundation bloodstock for the major studs of eastern Europe.[119][120]

Polish and Russian breeding programs

With the rise of light cavalry, the stamina and agility of horses with Arabian blood gave an enormous military advantage to any army who possessed them. As a result, many European monarchs began to support large breeding establishments that crossed Arabians on local stock, one example being Knyszyna, the royal stud of Polish king Zygmunt II August, and another the Imperial Russian Stud of Peter the Great.[119]

European horse breeders also obtained Arabian stock directly from the desert or via trade with the Ottomans. In Russia, Count Alexey Orlov obtained many Arabians, including Smetanka, an Arabian stallion who became a foundation sire of the Orlov trotter.[121][122] Orlov then provided Arabian horses to Catherine the Great, who in 1772 owned 12 pure Arabian stallions and 10 mares.[121] By 1889 two members of the Russian nobility, Count Stroganov and Prince Nikolai Borisovich Shcherbatov, established Arabian stud farms to meet the continued need to breed Arabians as a source of pure bloodstock.[117][121]

In Poland, notable imports from Arabia included those of Prince Hieronymous Sanguszko (1743–1812), who founded the Slawuta stud.[123][124] Poland's first state-run Arabian stud farm, Janów Podlaski, was established by the decree of Alexander I of Russia in 1817,[125] and by 1850, the great stud farms of Poland were well-established, including Antoniny, owned by the Polish Count Potocki (who had married into the Sanguszko family); later notable as the farm that produced the stallion Skowronek.[124][126]

Central and western Europe

The 18th century marked the establishment of most of the great Arabian studs of Europe, dedicated to preserving "pure" Arabian bloodstock. The Prussians set up a royal stud in 1732, originally intended to provide horses for the royal stables, and other studs were established to breed animals for other uses, including mounts for the Prussian army. The foundation of these breeding programs was the crossing of Arabians on native horses; by 1873 some English observers felt that the Prussian calvalry mounts were superior in endurance to those of the British, and credited Arabian bloodlines for this superiority.[127]

Other state studs included the Babolna Stud of Hungary, set up in 1789,[128] and the Weil stud in Germany (now Weil-Marbach or the Marbach stud), founded in 1817 by King William I of Württemberg.[129] King James I of England imported the first Arabian stallion, the Markham Arabian, to England in 1616.[130] Arabians were also introduced into European race horse breeding, especially in England via the Darley Arabian, Byerly Turk, and Godolphin Arabian, the three foundation stallions of the modern Thoroughbred breed, who were each brought to England during the 18th century.[131] Other monarchs obtained Arabian horses, often as personal mounts. One of the most famous Arabian stallions in Europe was Marengo, the war horse ridden by Napoleon Bonaparte.[132]

During the mid-19th century, the need for Arabian blood to improve the breeding stock for light cavalry horses in Europe resulted in more excursions to the Middle East. Queen Isabel II of Spain sent representatives to the desert to purchase Arabian horses and by 1847 had established a stud book; her successor, King Alfonso XII imported additional bloodstock from other European nations. By 1893, the state military stud farm, Yeguada Militar was established in Córdoba, Spain for breeding both Arabian and Iberian horses. The military remained heavily involved in the importation and breeding of Arabians in Spain well into the early 20th century, and the Yeguada Militar is still in existence today.[133]

This period also marked a phase of considerable travel to the Middle East by European civilians and minor nobility, and in the process, some travelers noticed that the Arabian horse as a pure breed of horse was under threat due to modern forms of warfare, inbreeding and other problems that were reducing the horse population of the Bedouin tribes at a rapid rate.[134] By the late 19th century, the most farsighted began in earnest to collect the finest Arabian horses they could find in order to preserve the blood of the pure desert horse for future generations. The most famous example was Lady Anne Blunt, the daughter of Ada Lovelace and granddaughter of Lord Byron.[135]

Rise of the Crabbet Park Stud

Perhaps the most famous of all Arabian breeding operations founded in Europe was the Crabbet Park Stud of England, founded 1878.[136][137] Starting in 1877, Wilfrid Scawen Blunt and Lady Anne Blunt made repeated journeys to the Middle East, including visits to the stud of Ali Pasha Sherif in Egypt and to Bedouin tribes in the Nejd, bringing the best Arabians they could find to England. Lady Anne also purchased and maintained the Sheykh Obeyd stud farm in Egypt, near Cairo. Upon Lady Anne's death in 1917, the Blunts' daughter, Judith, Lady Wentworth, inherited the Wentworth title and Lady Anne's portion of the estate, and obtained the remainder of the Crabbet Stud following a protracted legal battle with her father.[138][139] Lady Wentworth expanded the stud, added new bloodstock, and exported Arabian horses worldwide. Upon her death in 1957, the stud passed to her manager, Cecil Covey, who ran Crabbet until 1971, when a motorway was cut through the property, forcing the sale of the land and dispersal of the horses.[140] Along with Crabbet, the Hanstead Stud of Lady Yule also produced horses of worldwide significance.[141]

Early 20th-century Europe

In the early 20th century, the military was involved in the breeding of Arabian horses throughout Europe, particularly in Poland, Spain, Germany, and Russia; private breeders also developed a number of breeding programs.[142][143][144][145] Significant among the private breeders in continental Europe was Spain's Cristóbal Colón de Aguilera, XV Duque de Veragua, a direct descendant of Christopher Columbus, who founded the Veragua Stud in the 1920s.[133][146]

Modern warfare and its impact on European studs

Between World War I, the Russian Revolution, and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, many historic European stud farms were lost; in Poland, the Antoniny and Slawuta Studs were wiped out except for five mares.[147] Notable among the survivors was the Janów Podlaski Stud. The Russian Revolution, combined with the effects of World War I, destroyed most of the breeding programs in Russia, but by 1921, the Soviet government reestablished an Arabian program, the Tersk Stud, on the site of the former Stroganov estate,[117] which included Polish bloodstock as well as some importations from the Crabbet Stud in England.[148] The programs that survived the war re-established their breeding operations and some added to their studs with new imports of desert-bred Arabian horses from the Middle East. Not all European studs recovered. The Weil stud of Germany, founded by King Wilhelm I, went into considerable decline; by the time the Weil herd was transferred to the Marbach State Stud in 1932, only 17 purebred Arabians remained.[129][149]

The Spanish Civil War and World War II also had a devastating impact on horse breeding throughout Europe. The Veragua stud was destroyed, and its records lost, with the only survivors being the broodmares and the younger horses, who were rescued by Francisco Franco.[150][151] Crabbet Park, Tersk, and Janów Podlaski survived. Both the Soviet Union and the United States obtained valuable Arabian bloodlines as spoils of war, which they used to strengthen their breeding programs. The Soviets had taken steps to protect their breeding stock at Tersk Stud, and by utilizing horses captured in Poland they were able to re-establish their breeding program soon after the end of World War II. The Americans brought Arabian horses captured in Europe to the United States, mostly to the Pomona U.S. Army Remount station, the former W.K. Kellogg Ranch in California.[152]

In the postwar era, Poland,[153] Spain,[151] and Germany developed or re-established many well-respected Arabian stud farms.[154] The studs of Poland in particular were decimated by both the Nazis and the Soviets, but were able to reclaim some of their breeding stock and became particularly world-renowned for their quality Arabian horses, tested rigorously by racing and other performance standards.[155] During the 1950s, the Russians also obtained additional horses from Egypt to augment their breeding programs.[156]

After the Cold War

While only a few Arabians were exported from behind the Iron Curtain during the Cold War, those who did come to the west caught the eye of breeders worldwide. Improved international relations between eastern Europe and the west led to major imports of Polish and Russian-bred Arabian horses to western Europe and the United States in the 1970s and 1980s.[157] The collapse of the former Soviet Union in 1991, greater political stability in Egypt, and the rise of the European Union all increased international trade in Arabian horses. Organizations such as the World Arabian Horse Association (WAHO) created consistent standards for transferring the registration of Arabian horses between different nations. Today, Arabian horses are traded all over the world.[158]

In America

The first horses on the American mainland since the end of the Ice Age arrived with the Spanish Conquistadors. Hernán Cortés brought 16 horses of Andalusian, Barb, and Arabian ancestry to Mexico in 1519. Others followed, such as Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, who brought 250 horses of similar breeding to America in 1540.[159] More horses followed with each new arrival of Conquistadors, missionaries, and settlers. Many horses escaped or were stolen, becoming the foundation stock of the American Mustang.[160][161]

Early imports

Colonists from England also brought horses of Arabian breeding to the eastern seaboard. One example was Nathaniel Harrison, who imported a horse of Arabian, Barb and Turkish ancestry to America in 1747.[159]

One of George Washington's primary mounts during the American Revolutionary War was a gray half-Arabian horse named Blueskin, sired by the stallion "Ranger", also known as "Lindsay's Arabian", said to have been obtained from the Sultan of Morocco.[162][163] Other Presidents are linked to ownership of Arabian horses; in 1840, President Martin Van Buren received two Arabians from the Sultan of Oman,[159] and in 1877, President Ulysses S. Grant obtained an Arabian stallion, Leopard, and a Barb, Linden Tree, as gifts from Abdul Hamid II, the "Sultan of Turkey".[80][164][165]

A. Keene Richard was the first American known to have specifically bred Arabian horses. He traveled to the desert in 1853 and 1856 to obtain breeding stock, which he crossed on Thoroughbreds, and also bred purebred Arabians. Unfortunately, his horses were lost during the Civil War and have no known purebred Arabian descendants today.[166] Another major U.S. political figure, William H. Seward purchased four Arabians in Beirut in 1859, prior to becoming Secretary of State to Abraham Lincoln.[167]

Leopard is the only stallion imported prior to 1888 who left known purebred descendants in America.[168] In 1888 Randolph Huntington imported the desert-bred Arabian mare *Naomi, and bred her to Leopard, producing Leopard's only purebred Arabian son, Anazeh, who sired eight purebred Arabian foals, four of whom still appear in pedigrees today.[169]

Development of purebred breeding in America

In 1908, the Arabian Horse Registry of America was established, recording 71 animals,[164] and by 1994, the number had reached half a million. Today there are more Arabians registered in North America than in the rest of the world put together.[170]

The origins of the registry date to 1893, when the Hamidie Society sponsored an exhibit of Arabian horses from what today is Syria at the World Fair in Chicago.[164] This exhibition raised considerable interest in Arabian horses. Records are unclear if 40 or 45 horses were imported for the exposition, but seven died in a fire shortly after arrival. The 28 horses that remained at the end of the exhibition stayed in America and were sold at auction when the Hamidie Society went bankrupt.[171] These horses caught the interest of American breeders,[164][172] including Peter Bradley of the Hingham Stock Farm, who purchased some Hamidie horses at the auction, and Homer Davenport, another admirer of the Hamidie imports.[171]

Major Arabian importations to the United States included those of Davenport and Bradley, who teamed up to purchase several stallions and mares directly from the Bedouin in 1906.[172] Spencer Borden of the Interlachen Stud made several importations between 1898 and 1911;[164][173] and W.R. Brown of the Maynesboro Stud, interested in the Arabian as a cavalry mount, imported many Arabians over a period of years, starting in 1918.[164] Another wave of imports came in the 1920s and 30s when breeders such as W.K. Kellogg, Henry Babson, Roger Selby, James Draper, and others imported Arabian bloodstock from Crabbet Park Stud in England, as well as from Poland, Spain and Egypt.[164][174] The breeding of Arabians was fostered by the U. S. Army Remount Service, which stood purebred stallions at public stud for a reduced rate.[175]

Several Arabians, mostly of Polish breeding, were captured from Nazi Germany and imported to the U.S.A. following World War II.[176] In 1957, two deaths in England led to more sales to the United States: first from Crabbet Stud on the demise of Lady Wentworth,[177] and then from Hanstead with the passing of Gladys Yule.[141] As the tensions of the Cold War eased, more Arabians were imported to America from Poland and Egypt, and in the late 1970s, as political issues surrounding import regulations and the recognition of stud books were resolved, many Arabian horses were imported from Spain and Russia.[96][178]

Modern trends

In the 1980s, Arabians became a popular status symbol and were marketed similarly to fine art.[179] Some individuals also used horses as a tax shelter.[180] Prices skyrocketed, especially in the United States, with a record-setting public auction price for a mare named NH Love Potion, who sold for $2.55 million in 1984, and the largest syndication in history for an Arabian stallion, Padron, at $11 million.[181] The potential for profit led to over-breeding of the Arabian. When the Tax Reform Act of 1986 closed the tax-sheltering "passive investment" loophole, limiting the use of horse farms as tax shelters,[182][183] the Arabian market was particularly vulnerable due to over-saturation and artificially inflated prices, and it collapsed, forcing many breeders into bankruptcy and sending many purebred Arabians to slaughter.[183][184] Prices recovered slowly, with many breeders moving away from producing "living art" and towards a horse more suitable for amateur owners and many riding disciplines. By 2003, a survey found that 67% of purebred Arabian horses in America are owned for recreational riding purposes.[185] As of 2013, there are more than 660,000 Arabians that have been registered in the United States, and the US has the largest number of Arabians of any nation in the world.[186]

In Australia

Early imports

Arabian horses were introduced to Australia in the earliest days of European Settlement. Early imports included both purebred Arabians and light Spanish "jennets" from Andalusia, many Arabians also came from India. Based on records describing stallions "of Arabic and Persian blood", the first Arabian horses were probably imported to Australia in several groups between 1788 and 1802.[187] About 1803, a merchant named Robert Campbell imported a bay Arabian stallion, Hector, from India;[187] Hector was said to have been owned by Arthur Wellesley, who later became known as the Duke of Wellington.[188] In 1804 two additional Arabians, also from India, arrived in Tasmania one of whom, White William, sired the first purebred Arabian foal born in Australia, a stallion named Derwent.[187]

Throughout the 19th century, many more Arabians came to Australia, though most were used to produce crossbred horses and left no recorded purebred descendants.[187] The first significant imports to be permanently recorded with offspring still appearing in modern purebred Arabian pedigrees were those of James Boucaut, who in 1891 imported several Arabians from Wilfred and Lady Anne Blunt's Crabbet Arabian Stud in England.[189] Purebred Arabians were used to improve racehorses and some of them became quite famous as such; about 100 Arabian sires are included in the Australian Stud Book (for Thoroughbred racehorses).[188] The military was also involved in the promotion of breeding calvalry horses, especially around World War I.[189] They were part of the foundation of several breeds considered uniquely Australian, including the Australian Pony, the Waler and the Australian Stock Horse.[190]

In the 20th and 21st centuries

In the early 20th century, more Arabian horses, mostly of Crabbet bloodlines, arrived in Australia. The first Arabians of Polish breeding arrived in 1966, and Egyptian lines were first imported in 1970. Arabian horses from the rest of the world followed, and today the Australian Arabian horse registry is the second largest in the world, next to that of the United States.[191]

Modern breeding

_and_Dressage).jpg.webp)

Arabian horses today are found all over the world. They are no longer classified by Bedouin strain, but are informally classified by the nation of origin of famed horses in a given pedigree. Popular types of Arabians are labeled "Polish", "Spanish", "Crabbet", "Russian", "Egyptian", and "Domestic" (describing horses whose ancestors were imported to the United States prior to 1944, including those from programs such as Kellogg, Davenport, Maynesboro, Babson, Dickenson and Selby). In the US, a specific mixture of Crabbet, Maynesboro and Kellogg bloodlines has acquired the copyrighted designation "CMK".[192]

Each set of bloodlines has its own devoted followers, with the virtues of each hotly debated. Most debates are between those who value the Arabian most for its refined beauty and those who value the horse for its stamina and athleticism; there are also a number of breeders who specialize in preservation breeding of various bloodlines. Controversies exist over the relative "purity" of certain animals; breeders argue about the genetic "purity" of various pedigrees, discussing whether some horses descend from "impure" animals that cannot be traced to the desert Bedouin.[193] The major factions are as follows:

- The Arabian Horse Association (AHA) states, "The origin of the purebred Arabian horse was the Arabian desert, and all Arabians ultimately trace their lineage to this source." In essence, all horses accepted for registration in the United States are deemed to be "purebred" Arabians by AHA.[192]

- The World Arabian Horse Association (WAHO) has the broadest definition of a purebred Arabian. WAHO states, "A Purebred Arabian horse is one which appears in any purebred Arabian Stud Book or Register listed by WAHO as acceptable." By this definition, over 95% of the known purebred Arabian horses in the world are registered in stud books acceptable to WAHO.[194] WAHO also researched the purity question in general, and its findings are on its web site, describing both the research and the political issues surrounding Arabian horse bloodlines, particularly in America.[96]

- At the other end of the spectrum, organizations focused on bloodlines that are the most meticulously documented to desert sources have the most restrictive definitions. For example, The Asil Club in Europe only accepts "a horse whose pedigree is exclusively based on Bedouin breeding of the Arabian peninsula, without any crossbreeding with non-Arabian horses at any time".[195] Likewise, the Al Khamsa organization takes the position that "The horse...which are called "Al Khamsa Arabian Horses," are those horses in North America that can reasonably be assumed to descend entirely from bedouin Arabian horses bred by horse-breeding bedouin tribes of the deserts of the Arabian Peninsula without admixture from sources unacceptable to Al Khamsa."[196] Most restrictive of all are horses identified as "straight Egyptian" by the Pyramid Society, which must trace in all lines to the desert and also to horses owned or bred by specific Egyptian breeding programs.[197] By this definition, straight Egyptian Arabians constitute only 2% of all Arabian horses in America.[198]

- Ironically, some pure-blooded desert-bred Arabians in Syria had enormous difficulties being accepted as registrable purebred Arabians because many of the Bedouin who owned them saw no need to obtain a piece of paper to verify the purity of their horses. However, eventually the Syrians developed a stud book for their animals that was accepted by the World Arabian Horse Association (WAHO) in 2007.[199]

Influence on other horse breeds

Because of the genetic strength of the desert-bred Arabian horse, Arabian bloodlines have played a part in the development of nearly every modern light horse breed, including the Thoroughbred,[131] Orlov Trotter,[200] Morgan,[201] American Saddlebred,[202] American Quarter Horse,[201] and Warmblood breeds such as the Trakehner.[203] Arabian bloodlines have also influenced the development of the Welsh Pony,[201] the Australian Stock Horse,[201] Percheron draft horse,[204] Appaloosa,[205] and the Colorado Ranger Horse.[206]

Today, people cross Arabians with other breeds to add refinement, endurance, agility and beauty. In the US, Half-Arabians have their own registry within the Arabian Horse Association, which includes a special section for Anglo-Arabians (Arabian-Thoroughbred crosses).[207] Some crosses originally registered only as Half-Arabians became popular enough to have their own breed registry, including the National Show Horse (an Arabian-Saddlebred cross),[208] the Quarab (Arabian-Quarter Horse),[209] the Pintabian[210] the Welara (Arabian-Welsh Pony),[211] and the Morab (Arabian-Morgan).[212] In addition, some Arabians and Half Arabians have been approved for breeding by some Warmblood registries, particularly the Trakehner registry.[213]

There is intense debate over the role the Arabian played in the development of other light horse breeds. Before DNA-based research developed, one hypothesis, based on body types and conformation, suggested the light, "dry", oriental horse adapted to the desert climate had developed prior to domestication;[214] DNA studies of multiple horse breeds now suggest that while domesticated horses arose from multiple mare lines, there is very little variability in the Y-chromosome between breeds.[215] Following domestication of the horse, due to the location of the Middle East as a crossroads of the ancient world, and relatively near the earliest locations of domestication,[216] oriental horses spread throughout Europe and Asia both in ancient and modern times. There is little doubt that humans crossed "oriental" blood on that of other types to create light riding horses; the only actual questions are at what point the "oriental" prototype could be called an "Arabian", how much Arabian blood was mixed with local animals, and at what point in history.[99][217]

For some breeds, such as the Thoroughbred, Arabian influence of specific animals is documented in written stud books.[218] For older breeds, dating the influx of Arabian ancestry is more difficult. For example, while outside cultures, and the horses they brought with them, influenced the predecessor to the Iberian horse in both the time of Ancient Rome and again with the Islamic invasions of the 8th century, it is difficult to trace precise details of the journeys taken by waves of conquerors and their horses as they traveled from the Middle East to North Africa and across Gibraltar to southern Europe. Mitochondrial DNA studies of modern Andalusian horses of the Iberian peninsula and Barb horses of North Africa present convincing evidence that both breeds crossed the Strait of Gibraltar and influenced one another.[219] Though these studies did not compare Andalusian and Barb mtDNA to that of Arabian horses, there is evidence that horses resembling Arabians, whether before or after the breed was called an "Arabian", were part of this genetic mix. Arabians and Barbs, though probably related to one another, are quite different in appearance,[220] and horses of both Arabian and Barb type were present in the Muslim armies that occupied Europe.[133] There is also historical documentation that Islamic invaders raised Arabian horses in Spain prior to the Reconquista;[221] the Spanish also documented imports of Arabian horses in 1847, 1884 and 1885 that were used to improve existing Spanish stock and revive declining equine populations.[133]

Uses

Arabians are versatile horses that compete in many equestrian fields, including horse racing, the horse show disciplines of saddle seat, Western pleasure, and hunt seat, as well as dressage, cutting, reining, endurance riding, show jumping, eventing, youth events such as equitation, and others. They are used as pleasure riding, trail riding, and working ranch horses for those who are not interested in competition.[222]

Competition

Arabians dominate the sport of endurance riding because of their stamina. They are the leading breed in competitions such as the Tevis Cup that can cover up to 100 miles (160 km) in a day,[223] and they participate in FEI-sanctioned endurance events worldwide, including the World Equestrian Games.[224]

There is an extensive series of horse shows in the United States and Canada for Arabian, Half-Arabian, and Anglo-Arabian horses, sanctioned by the USEF in conjunction with the Arabian Horse Association. Classes offered include Western pleasure, reining, hunter type and saddle seat English pleasure, and halter, plus the very popular "Native" costume class.[225][226] "Sport horse" events for Arabian horses have become popular in North America, particularly after the Arabian Horse Association began hosting a separate Arabian and Half Arabian Sport Horse National Championship in 2003[227] that by 2004 grew to draw 2000 entries.[228] This competition draws Arabian and part-Arabian horses that perform in hunter, jumper, sport horse under saddle, sport horse in hand, dressage, and combined driving competition.[229]

.jpg.webp)

Other nations also sponsor major shows strictly for purebred and partbred Arabians, including Great Britain[230] France,[231] Spain,[232] Poland,[233] and the United Arab Emirates.[234]

Purebred Arabians have excelled in open events against other breeds. One of the most famous examples in the field of western riding competition was the Arabian mare Ronteza, who defeated 50 horses of all breeds to win the 1961 Reined Cow Horse championship at the Cow Palace in San Francisco, California.[235][236] Another Arabian competitive against all breeds was the stallion Aaraf who won an all-breed cutting horse competition at the Quarter Horse Congress in the 1950s.[237] In show jumping and show hunter competition, a number of Arabians have competed successfully against other breeds in open competition,[236] including the purebred gelding Russian Roulette, who has won multiple jumping classes against horses of all breeds on the open circuit,[238] and in eventing, a purebred Arabian competed on the Brazilian team at the 2004 Athens Olympics.[239]

Part-Arabians have also appeared at open sport horse events and even Olympic level competition. The Anglo-Arabian Linon was ridden to an Olympic silver medal for France in Dressage in 1928 and 1932, as well as a team gold in 1932, and another French Anglo-Arabian, Harpagon, was ridden to a team gold medal and an individual silver in dressage at the 1948 Olympics.[240][241] At the 1952 Olympics, the French rider Pierre d'Oriola won the Gold individual medal in show jumping on the Anglo-Arabian Ali Baba.[242] Another Anglo-Arabian, Tamarillo, ridden by William Fox-Pitt, represents the United Kingdom in FEI and Olympic competition, winning many awards, including first place at the 2004 Badminton Horse Trials.[243] More recently a gelding named Theodore O'Connor, nicknamed "Teddy", a 14.1 (or 14.2, sources vary) hand pony of Thoroughbred, Arabian, and Shetland pony breeding, won two gold medals at the 2007 Pan American Games and was finished in the top six at the 2007 and 2008 Rolex Kentucky Three Day CCI competition.[244]

Other activities

Arabians are involved in a wide variety of activities, including fairs, movies, parades, circuses and other places where horses are showcased. They have been popular in movies, dating back to the silent film era when Rudolph Valentino rode the Kellogg Arabian stallion Jadaan in 1926's Son of the Sheik,[245] and have been seen in many other films, including The Black Stallion featuring the stallion Cass Ole,[246] The Young Black Stallion, which used over 40 Arabians during filming,[247] as well as Hidalgo[248] and the 1959 version of Ben-Hur.[249]

Arabians are mascots for football teams, performing crowd-pleasing activities on the field and sidelines. One of the horses who serves as "Traveler", the mascot for the University of Southern California Trojans, has been a purebred Arabian. "Thunder", a stage name for the purebred Arabian stallion J B Kobask, was mascot for the Denver Broncos from 1993 until his retirement in 2004, when the Arabian gelding Winter Solstyce took over as "Thunder II".[250] Cal Poly Pomona's W.K. Kellogg Arabian Horse Center Equestrian Unit has made Arabian horses a regular sight at the annual Tournament of Roses Parade held each New Year's Day in Pasadena, California.[251]

Arabians also are used on search and rescue teams and occasionally for police work. Some Arabians are used in polo in the US and Europe, in the Turkish equestrian sport of Cirit (pronounced [dʒiˈɾit]), as well as in circuses, therapeutic horseback riding programs, and on guest ranches.

Notes

- Upton, Arabians pp. 21–22

- Archer, Arabian Horse, pp. 89–92

- United States Equestrian Federation. "Chapter AR: Arabian, Half-Arabian and Anglo-Arabian Division Rule Book, Rule AR-102" (PDF). 2008 Rule book. United States Equestrian Federation. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2009. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- Edwards, Gladys Brown (January 1989). "How I Would 'Build' an Arabian Stallion". Arabian Horse World. p. 542. Reprinted in Parkinson, pp. 157–158

- Schofler, Flight Without Wings, pp. 11–12

- Arabian Horse Association. "Arabians are beautiful, but are they good athletes? - The Versatile Arabian". AHA Website. Arabian Horse Association. Archived from the original on June 12, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- Edwards, The Arabian, pp. 245–246

- Arabian Horse Society of Australia. "Arabians In Endurance". AHSA Website. Arabian Horse Society of Australia. Archived from the original on April 30, 2008. Retrieved May 31, 2008.

- Edwards, The Arabian, pp. 27–28

- Schofler, Flight Without Wings, p. 8

- Typically the hip angle is about 35 degrees, while the croup is about 25 degrees

- Edwards, "Chapter 6: The Croup", Anatomy and Conformation of the Horse, pp. 83–98

- Edwards, Gladys Brown. "An Illustrated Guide to Arabian Horse Conformation." Arabian Horse World Quarterly, Spring, 1998, p. 86. Reprinted in Parkinson, p. 121

- Plumb, Types and Breeds of Farm Animals, p. 168

- Ensminger, Horses and Horsemanship p. 96

- Ensminger, Horses and Horsemanship p. 84

- Arabian Horse Association. "The Arabian Horse Today". Arabian Horse History & Heritage. Arabian Horse Association. Archived from the original on May 13, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- Upton, Arabians, p. 19

- Stallions may be shown in most youth classes, except for 8 and under walk-trot: 2008 USEF Arabian, Half-Arabian and Anglo-Arabian Division Rule Book, Rule AR-112 Archived March 3, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

Breeds not allowing stallions in youth classes include, but are not limited to, Rule 404(c) American Quarter Horse Archived February 7, 2013, at the Wayback Machine; Rule 607 Appaloosa; SB-126 Saddlebreds; PF-106 Paso Finos - no children under 13; MO-104 Morgans; 101 Children's and Junior Hunters; HP-101 Hunter Pony; HK-101 Hackney; FR-101 Friesians; EQ-102 Equitation - stallions prohibited except if limited only to breeds that allow stallions; CP-108 Carriage and Pleasure Driving; WS 101 Western division.

Other breeds allowing stallions in youth classes include AL-101, Andalusians, CO-103 Connemaras and (WL 115 and WL 139 Welch pony and cob - Pavord, Handling and Understanding the Horse, p. 19

- Rashid, A Good Horse Is Never a Bad Color, p. 50

- "Hot-blooded Horses: What are the hotblood breeds?". American Horse Rider & Horses and Horse Information. 2007. (example of information claiming hot-blooded horses are hard to manage). Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- Edwards, The Arabian, p. 28

- Arabian Horse Association. "How Do I... Determine Color & Markings?". Purebred Registration. Arabian Horse Association. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- Ammon, Historical Reports on Arab Horse Breeding and the Arabian Horse, p. 152

- Sponenberg, Equine Color Genetics, p. 69

- Wahler, Brenda (2011). "Arabian Coat Color Patterns" (PDF). Arabian Horse Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 29, 2011. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- Stewart, The Arabian Horse, p. 34

- Arabian Horse Association. "What Color Is My Horse?". Purebred Registration. Arabian Horse Association. Archived from the original on May 14, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- "Leg Up" (PDF). Arabian Horse Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 17, 2010. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- Upton, Peter (1987). The Classic Arabian. Arab Horse Society. p. 33. OCLC 21241803.

- Haase B, Brooks SA, Schlumbaum A, Azor PJ, Bailey E, et al. (2007). "Allelic Heterogeneity at the Equine KIT Locus in Dominant White (W) Horses". PLOS Genetics. 3 (11): e195. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030195. PMC 2065884. PMID 17997609.

- UC Davis. "Horse Coat Color Tests". Veterinary Genetics Laboratory. University of California - Davis. Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved January 11, 2008.

- "Sabino 1". Animal Genetics Incorporated. Archived from the original on October 10, 2009. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- UC Davis. "Introduction to Coat Color Genetics". Veterinary Genetics Laboratory. University of California - Davis. Archived from the original on January 20, 2008. Retrieved January 11, 2008.

- Horse Genetics. "Roan Horses". The Horse Genetics Web Site. Horse Genetics. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- "Introduction to Coat Color Genetics". University of California Davis Veterinary Genetics Lab. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- Edwards, The Arabian, p. 5

- Beaver, Horse color, p. 98

- Gower, Horse Color Explained, p. 30

- Arabian Horse Society of Australia. "The Arabian Derivative Horse" (PDF). Derivative Standard 2004. Arabian Horse Society of Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 22, 2008. Retrieved June 30, 2008.

- Walker, Dawn (February 1997). "Lethal Whites: A Light at the End of the Tunnel". Paint Horse Journal. Archived from the original on December 12, 2007. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- Parry, "xc overo/lethal white", Compendium, pp. 945–950

- Goodwin-Campiglio, et al. "Caution and Knowledge", pp. 100–105

- "Applications of Genome Study - Simple Hereditary Diseases". Horse Genome Project. 2007.

- VetGen. "SCID". List of Services. VetGen. Archived from the original on May 24, 2008. Retrieved May 29, 2008.

- Bird, Helen. "Lavender Foal Syndrome Fact Sheet". James A Baker Institute for Animal Health. Cornell University. Retrieved May 29, 2008.

- Fanelli, H. H. (2010). "Coat colour dilution lethal ('lavender foal a'): Syndrome tetany syndrome of Arabian foals". Equine Veterinary Education. 17 (5): 260–263. doi:10.1111/j.2042-3292.2005.tb00386.x.

- "Bierman, A., 4 November 2009, Lavender Foal Syndrome - Genetic test developed in South Africa" Archived October 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Johnson, Robert S. (September 23, 2008). "Test Allows Arabian Breeders to Scan for Inherited Neurologic Disorder". The Horse online edition. Blood-Horse Publications. Retrieved October 1, 2008.

- UC Davis. "Cerebellar Abiotrophy". Veterinary Genetics Laboratory. University of California - Davis. Archived from the original on June 20, 2008. Retrieved May 29, 2008.

- Watson, A.G; Mayhew, I.G. (May 1986). "Familial congenital occipitoatlantoaxial malformation (OAAM) in the Arabian horse". Spine. 11 (4): 334–339. doi:10.1097/00007632-198605000-00007. PMID 3750063. S2CID 24162295.

- "Occipitoatlantoaxial Malformation (OAAM) | School of Veterinary Medicine". UC Davis Veterinary Medicine. University of California, Davis. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- Equus Staff, "Good news about recovery from foal epilepsy", Equus

- Judd, Bob. "Lavender Foal Syndrome". Texas Vet News. Veterinary Information Network. Retrieved November 24, 2006.

- Aleman, Monica (November–December 2006). "Juvenile idiopathic epilepsy in Egyptian Arabian foals: 22 cases (1988-2005)". Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 20 (6): 1443–9. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1676.2006.tb00764.x. PMID 17186863. Archived from the original on January 5, 2013.

- Blazyczek, Ingild Astrid. "Populationsgenetische Analyse der Luftsacktympanie beim Fohlen" (En: "Population genetic analysis of guttural pouch tympany in foals")". Dissertation. Hannover, Tierärztliche Hochschule. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- Marcella, "The mysterious guttural pouch", Thoroughbred Times

- Blazyczek, "Inheritance of Guttural Pouch Tympany in the Arabian Horse", Journal of Heredity, pp. 195–199

- Krause, Myron. "HA President's Bulletin, December 2007". AHA Website. Arabian Horse Association. Archived from the original on January 21, 2008. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- F.O.A.L. "Arabian Foal Association Homepage". AFA Homepage. Arabian F.O.A.L. Association. Archived from the original on May 29, 2008. Retrieved May 29, 2008.

- Goodwin-Campiglio, Lisa. "Genetic Disorders in Arabian Horses: Current Research Projects". World Arabian Horse Association (WAHO) Website. World Arabian Horse Association. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved October 23, 2007.

- Barkham, Patrick (October 12, 2017). "Vets warn that 'extreme breeding' could harm horses". The Guardian.

- "Trend for extreme breeding is now affecting horses | BMJ".

- Al Khamsa. "Al Khamsa The Five". History and Legends. Al Khamsa, Inc. Archived from the original on April 18, 2008. Retrieved May 29, 2008.

- Archer, Arabian Horse, pp. 92–93

- Upton, Arabians, p. 12

- Schofler, Flight Without Wings, pp. 3–4

- Chamberlin, Horse, pp. 166–167

- Archer, Arabian Horse, p. 2

- Raswan, The Raswan Index and Handbook for Arabian Breeders, Section: "The Kuhaylat", p. 6

- Beck, Andy. "The Arabian: a treasure of nature to be preserved". Natural Horse Planet. Planet Equitopia SARL. credited as Ancient Bedouin Legend per "Byford, et al. Origination of the Arabian Breed". Archived from the original on April 26, 2012. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- Sumi, Description in Classical Arabic Poetry, p. 19

- Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia. "Preserving the Arabian Horse in its Ancestral Land". Spring 2007 Publication. Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia. Archived from the original on August 4, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- Edwards, The Arabian, p. 2

- Edwards, The Arabian, p. 27

- Bennett, Conquerors, pp. 4–7

- Głażewska, Iwona (April 1, 2010). "Speculations on the origin of the Arabian horse breed". Livestock Science. 129 (1–3): 49–55. doi:10.1016/j.livsci.2009.12.009. ISSN 1871-1413.

- Edwards, The Arabian, pp.6–7

- Kentucky Horse Park. "Arabian". International Museum of the Horse. Kentucky Horse Park. Archived from the original on October 23, 2007. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- "Discovery at al-Magar". Saudi Aramco World. Archived from the original on April 14, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- Lumpkin, "Camels: Of Service and Survival", Zoogoer

- Bennett, Deb. "Introduction - Part 2: The Origin and Relationships of the Mustang, Barb, and Arabian Horse". The Spanish Mustang. The Horse of the Americas Registry. Archived from the original on May 6, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- Edwards, The Arabian, p. 24

- Archer, Arabian Horse, pp. 2–4

- Arabian Horse Association. "Arabian Type, Color and Conformation". FAQ. Arabian Horse Association. Archived from the original on June 12, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- Schofler, "Daughters of the Desert", Equestrian Magazine

- Edwards, The Arabian, pp. 24–26

- "The Horse of the Bedouin". The Bedouin Horse. Al Khamsa Organization. Archived from the original on November 19, 2010. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- Derry Bred for Perfection pp. 104–105

- Arabian Horse Association. "Horse of the Desert Bedouin". Arabian Horse History & Heritage. Arabian Horse Association. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- Archer, Arabian Horse, p. 92

- Forbis Classic Arabian Horse pp. 274–289

- "The Bedouin Concept of Asil". The Bedouin Horse. Al Khamsa Organization. Archived from the original on November 19, 2010. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- Edwards, The Arabian, p. 22

- World Arabian Horse Organization (WAHO). "Is Purity the Issue?". WAHO Publication Number 21, January 1998. World Arabian Horse Organization. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved March 12, 2015.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Lewis, Barbara S. "Egyptian Arabians: The Mystique Unfolded". Arabians. Pyramid Arabians. Archived from the original on May 8, 2006. Retrieved May 10, 2006.

- Bowling, "A pedigree-based study of mitochondrial d-loop DNA sequence variation among Arabian horses", Animal Genetics, p. 1

- Edwards, The Arabian, p. 16

- Upton, Arabians, p. 10

- Bennett, Conquerors, p. 130

- "The Arabian Horse: At War". Saudi Aramco World. Archived from the original on May 7, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- Greely, Arabian Exodus, pp. 26–27

- Derry, Horse and Society, p. 106

- Archer, Arabian Horse, p. 6

- Wentworth, The Authentic Arabian Horse, p. 178

- Edwards, The Arabian, p. 268

- Greely Arabian Exodus pp. 27–33

- Wentworth, The Authentic Arabian Horse, pp. 191–192

- Jobbins, "Straight Down the Line", Al-Ahram Weekly Online

- Greely, Arabian Exodus, p. 41

- Lewis, Barbara. "Egyptian Arabians". Arabian Horse - Bloodlines. Arabian Horse Association. Archived from the original on July 6, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2008.

- Greely, Arabian Exodus, p. 137

- Greely, Arabian Exodus, p. 149

- Greely, Arabian Exodus, p. 139

- Derry Bred for Perfection p. 123

- Himes, Cheryl. "Russian Arabians". Arabian Horse - Bloodlines. Arabian Horse Association. Archived from the original on July 12, 2008. Retrieved June 30, 2008.

- Carpenter Arabian Legends p. 102-111

- Harrigan, "The Polish Quest For Arabian Horses", Saudi Aramco World

- Derry Bred for Perfection p. 107

- Troika. "History of the Russian Arabian". Russian Arabians. Mekka Consulting. Archived from the original on May 30, 2000. Retrieved May 9, 2006.

- Greely, Arabian Exodus, p. 178

- Greely, Arabian Exodus, p. 172

- Derry, Bred for Perfection, pp. 107–108

- Krzysztalowicz, Andrzej. "History of the Stud". Janów Podlaski Website. Janów Podlaski Stud. Retrieved June 3, 2008.