LGBT rights in Africa

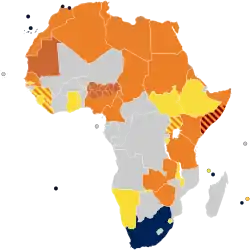

With the exception of South Africa and Cape Verde, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Africa are limited in comparison to Western Europe and much of the Americas and Oceania.

Same-sex marriage

Homosexuality legal but no recognition

Illegal but unenforced

Punishable by prison

Prison, unenforced death penalty

Enforced death penalty | |

| Status | Legal in 22 out of 54 countries Legal in all 8 territories |

| Gender identity | Legal in 3 out of 54 countries Legal in 7 out of 8 territories |

| Military | Allowed to serve openly in 1 out of 54 countries Allowed in all 8 territories |

| Discrimination protections | Protected in 7 out of 54 countries Protected in all 8 territories |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships | Recognized in 1 out of 54 countries Recognized in all 8 territories |

| Restrictions | Same-sex marriage constitutionally banned in 9 out of 54 countries |

| Adoption | Legal in 1 out of 54 countries Legal in all 8 territories |

Out of the 54 states recognised by the United Nations or African Union or both, the International Gay and Lesbian Association stated in 2015 that homosexuality is outlawed in 34 African countries.[1] Human Rights Watch notes that another two countries, Benin and the Central African Republic, do not outlaw homosexuality, but have certain laws which apply differently to heterosexual and homosexual individuals.[2]

Homosexuality has never been criminalised in Benin, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Madagascar, Mali, Niger, and Rwanda. It has been decriminalised in Angola, Botswana, Cape Verde, Gabon, Guinea-Bissau, Lesotho, Mozambique, São Tomé and Príncipe, the Seychelles and South Africa.

Since 2011, some developed countries have been considering or implementing laws that limit or prohibit general budget support to countries that restrict the rights of LGBT people.[3] In spite of this, many African countries have refused to consider increasing LGBT rights,[4] and in some cases have drafted laws to increase sanctions against LGBT people.[5] Some African leaders claim that it was brought into the continent from other parts of the world. Nevertheless, most scholarship and research demonstrates that homosexuality has long been a part of various African cultures.[6][7][8][9]

In Somalia, Somaliland, Mauritania and northern Nigeria, homosexuality is punishable by death.[1][10] In Uganda, Tanzania, and Sierra Leone, offenders can receive life imprisonment for homosexual acts, although the law is not enforced in Sierra Leone. In addition to criminalizing homosexuality, Nigeria has enacted legislation that would make it illegal for heterosexual family members, allies and friends of LGBT people to be supportive. According to Nigerian law, a heterosexual ally "who administers, witnesses, abets or aids" any form of gender non-conforming and homosexual activity could receive a 10-year jail sentence.[11] South Africa has the most liberal attitudes toward gays and lesbians, as the country has legalized same-sex marriage and its Constitution guarantees gay and lesbian rights and protections. However, violence and social discrimination against South African LGBT people is still widespread, fueled by a number of religious and political figures. The Spanish, Portuguese, British and French territories legalised same-sex marriages.[12][13]

For their own safety, gay and lesbian travellers have been encouraged by some to use discretion whilst in Africa, including advice to avoid public displays of affection (advice which applies equally to both homosexual and heterosexual couples).[14] South Africa is generally considered to be the most gay-friendly African country in respect of the legal status of LGBT rights, although Cape Verde is also frequently regarded as being very socially accepting of LGBT rights,[15] as described in the documentary Tchindas.

History of male homosexuality in Africa

Egypt

It remains unclear, what exact view the ancient Egyptians fostered about homosexuality. Any document and literature that actually contains sexual orientated stories, never named the nature of the sexual deeds, but instead uses stilted and flowery paraphrases. Ancient Egyptian documents never clearly say that same-sex relationships were seen as reprehensible or despicable. No ancient Egyptian document mentions that homosexual acts were set under penalty. Thus, a straight evaluation remains problematic.[16][17]

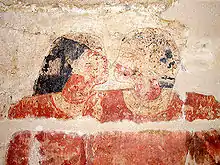

The best known case of possible homosexuality in ancient Egypt is that of the two high officials Nyankh-Khnum and Khnum-hotep. Both men lived and served under pharaoh Niuserre during the 5th Dynasty (c. 2494–2345 BC).[16] Nyankh-Khnum and Khnum-hotep each had families of their own with children and wives, but when they died their families apparently decided to bury them together in one and the same mastaba tomb. In this mastaba, several paintings depict both men embracing each other and touching their faces nose-on-nose. These depictions leave plenty of room for speculation, because in ancient Egypt the nose-on-nose touching normally represented a kiss.[16]

Egyptologists and historians disagree about how to interpret the paintings of Nyankh-khnum and Khnum-hotep. Some scholars believe that the paintings reflect an example of homosexuality between two married men and prove that the ancient Egyptians accepted same-sex relationships.[18] Other scholars disagree and interpret the scenes as an evidence that Nyankh-khnum and Khnum-hotep were twins, even possibly conjoined twins. No matter what interpretation is correct, the paintings show at the very least that Nyankh-khnum and Khnum-hotep must have been very close to each other in life as in death.[16]

The Roman Emperor Constantine in the 4th century AD is said to have exterminated a large number of "effeminate priests" based in Alexandria.[6]

North Africa

North Africa contained some of the most visible and well-documented traditions of homosexuality in the world – particularly during the period of Mamluk rule. Arabic poetry emerging from cosmopolitan and literate societies frequently described the pleasures of pederastic relationships. There are accounts of Christian boys being sent from Europe to become sex workers in Egypt. In Cairo, cross-dressing men called "khawal" would entertain audiences with song and dance (potentially of pre-Islamic origin).[6]

The Siwa Oasis in Egypt was described by several early twentieth century travellers as a place where same-sex sexual relationships were quite common. A group of warriors in this area were known for paying reverse dowries to younger men; a practice that was outlawed in the 1940s.[6]

Siegfried Frederick Nadel wrote about the Nuba tribes in Sudan the late 1930s.[19] He noted that among the Otoro, a special transvestitic role existed whereby men dressed and lived as women. Transvestitic homosexuality also existed amongst the Moru, Nyima, and Tira people, and reported marriages of Korongo londo and Mesakin tubele for the bride price of one goat. In the Korongo and Mesakin tribes, Nadel reported a common reluctance among men to abandon the pleasure of all-male camp life for the fetters of permanent settlement.

East Africa

In Ethiopia, homosexuality and sodomy were initially criminalized after the Kingdom of Aksum and laws were adopted from the Solomonic dynasty in thirteenth century.

At around of 1240, the Coptic Egyptian Christian writer Abul Fada'il Ibn al-'Assal compiled a legal code known as Fetha Nagast. Written in Ge'ez language, Ibn al-'Assal referred his laws from apostolic writer and former laws of Byzantine Empire. Fetha Nagast was written in two parts: the first dealt with the Church hierarchy sacraments and connected to religious rites. The second concerned laity, civil administration such as family laws. The code was effective in Zemene Mesafint because it was enacted as a supreme law. Outside the code, people's attitudes were disapproving of homosexuality. Fetha Nagast was repealed from the monarchy in 1931, at the reign of Emperor Haile Selassie, fearing that the laws were making unusual punishments such as amputations and criticized crime against humanity. Religious laws were halted when the Derg administration approved some legal changes regarding sexual orientation. Mengistu Hailemariam addressed homosexuality and usually mocked them during several press conferences. He reportedly criticized the troops and peasants of neglect controls through military and rural areas as a result of practicing same-sexual activities and residing in camps. In 1995, the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia was formed at the rule of Prime Minister Meles Zenawi. Homosexual and sodomite laws mitigated the punishment of past government systems, into imprisonment less than fifteen years. [20]

Gender-nonconforming and homosexuality has been reported in a number of East African societies. In pre-colonial East Africa there have been examples of male priests in traditional religions dressing as women. British social anthropologist Rodney Needham has described such a religious leadership role called "mugawe" among the Meru people and Kikuyu people of Kenya which included wearing women's clothes and hairstyle.[21] Mugawe are frequently homosexual, and sometimes are formally married to a man.

Such men were known as "ikihindu" among the Hutu and Tutsi peoples of Burundi and Rwanda. A similar role is played by some men within the Swahili-speaking Mashoga—who often take on women's names and cook and clean for their husbands.[6]

Swedish anthropologist Felix Bryk reported active (i.e., insertive) Kikuyu pederasts called onek, and also mentioned "homo-erotic bachelors" among the pastoralist Nandi and Maragoli (Wanga). The Nandi as well as the Maasai would sometimes cross-dress as women during initiation ceremonies.

Among the Maale people of southern Ethiopia, historian Donald Donham documented "a small minority [of men] crossed over to feminine roles. Called "ashtime", these (biological) males dressed like women, performed female tasks, cared for their own houses, and apparently had sexual relations with men,". They were also protected by the king.

In Uganda, religious roles for cross-dressing men (homosexual priests) were historically found among the Bunyoro people. Similarly, the kingdom of Buganda (part of modern-day Uganda) institutionalised certain forms of same-sex relations. Young men served in the royal courts and provided sexual services for visitors and elites. King Mwanga II of Buganda had several such men executed when they converted to Christianity and refused to carry out their assigned duties (the "Uganda Martyrs").[6][22] The Teso people of Uganda also have a category of men who dress as women.

West Africa

In West Africa there is extensive historical evidence of homosexuality. In the 18th and 19th century Asante courts (modern day Ghana) male slaves served as concubines. They dressed like women and were killed when their master died. In the kingdom of Dahomey, eunuchs were known as royal wives and played an important part at court.

The Dagaaba people, who lived in Burkina Faso believed that homosexual men were able to mediate between the spirit and human worlds.

Southern Africa

Writing in the 19th century about the area of today's southwestern Zimbabwe, David Livingstone asserted that the monopolization of women by elderly chiefs was essentially responsible for the "immorality" practised by younger men.[23] Edwin W. Smith and A. Murray Dale mention one Ila-speaking man who dressed as a woman, did women's work, lived and slept among, but not with, women. The Ila label "mwaami" they translated as "prophet". They also mentioned that pederasty was not rare, "but was considered dangerous because of the risk that the boy will become pregnant".[24]

Marc Epprecht's review of 250 court cases from 1892 to 1923 found cases from the beginnings of the records. The five 1892 cases all involved black Africans. A defense offered was that "sodomy" was part of local "custom". In one case a chief was summoned to testify about customary penalties and reported that the penalty was a fine of one cow, which was less than the penalty for adultery. Over the entire period, Epprecht found the balance of black and white defendants proportional to that in the population. He notes, however, only what came to the attention of the courts—most consensual relations in private did not necessarily provoke notice. Some cases were brought by partners who had been dropped or who had not received promised compensation from their former sexual partner. And although the norm was for the younger male to lie supine and not show any enjoyment, let alone expect any sexual mutuality, Epprecht found a case in which a pair of black males had stopped their sexual relationship out of fear of pregnancy, but one wanted to resume taking turns penetrating each other.[24]

Legislation by country or territory

| List of countries or territories by LGBT rights in Africa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

This table:

Northern Africa

Western Africa

Central Africa

Southeast Africa

Horn of Africa

Indian Ocean states

Southern Africa

|

Views of African leaders on homosexuality

The former president of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe, had been uncompromising in his opposition to LGBT rights in Zimbabwe. In September 1995, Zimbabwe's parliament introduced legislation banning homosexual acts.[98] In 1997, a court found Canaan Banana, Mugabe's predecessor and the first President of Zimbabwe, guilty of 11 counts of sodomy and indecent assault.[99] Mugabe has previously referred to LGBT people as being "worse than dogs and pigs".[100]

In the Gambia, former President Yahya Jammeh led the call for legislation that would set laws against homosexuals that would be "stricter than those in Iran", and that he would "cut off the head" of any gay or lesbian person discovered in the country.[101] News reports indicated his government intended to execute all homosexuals in the country.[101] In the speech given in Tallinding, Jammeh gave a "final ultimatum" to any gays or lesbians in the Gambia to leave the country.[101] In a speech to the United Nations on 27 September 2013, Jammeh said that "[h]omosexuality in all its forms and manifestations which, though very evil, antihuman as well as anti-Allah, is being promoted as a human right by some powers", and that those who do so "want to put an end to human existence".[102] In 2014, Jammeh called homosexuals "vermins" by saying that "We will fight these vermins called homosexuals or gays the same way we are fighting malaria-causing mosquitoes, if not more aggressively". He also went on to disparage LGBT people by saying that "As far as I am concerned, LGBT can only stand for Leprosy, Gonorrhoea, Bacteria and Tuberculosis; all of which are detrimental to human existence".[103][104] In 2015, in defiance of western criticism Jammeh intensified his anti-gay rhetoric, telling a crowd during an agricultural tour: "If you do it [in the Gambia] I will slit your throat—if you are a man and want to marry another man in this country and we catch you, no one will ever set eyes on you again, and no white person can do anything about it."[105]

In Uganda there have been recent efforts to institute the death penalty for homosexuality.[106][107] British newspaper The Guardian reported that President Yoweri Museveni "appeared to add his backing" to the legislative effort by, among other things, claiming "European homosexuals are recruiting in Africa", and saying gay relationships were against God's will.[108]

Abune Paulos, the late Patriarch of the ancient Ethiopian Orthodox Church, which has a very strong influence in Christian Ethiopia, stated homosexuality is an animal-like behaviour that must be punished.

Chad in 2017 passed a law criminalizing sodomy. Previously, the country never had any laws against consensual same-sex activity. Conversely, some African states like Lesotho, São Tomé and Príncipe, Mozambique, the Seychelles, Angola, and Botswana have abolished sodomy laws in recent years. Legalisation is proposed in Mauritius, Tunisia, Namibia, and Morocco. Gabon passed a law criminalizing sodomy in 2019, and reversed its decision by once again decriminalizing homosexuality a year later in 2020.

See also

References

- "State Sponsored Homophobia 2016: A world survey of sexual orientation laws: criminalisation, protection and recognition" (PDF). International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. 17 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- Ferreira, Louise (28 July 2015). "How many African states outlaw same-sex relations? (At least 34)". Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ""Cameron threat to dock some UK aid to anti-gay nations", BBC News, 30 October 2011". BBC News. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ""Ghana refuses to grant gays' rights despite aid threat", BBC News, 2 November 2011". BBC News. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ""Uganda fury at David Cameron aid threat over gay rights", BBC News, 31 October 2011". BBC News. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- Anthony Appiah and Henry Louis Gates, Encyclopedia of Africa, Volume 2 OUP, USA, 2010

- "South Africa: LGBT Groups Respond To Contralesa's Stance on Same Sex Marriage | OutRight Action International". Outrightinternational.org. 26 October 2006. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- Shaw, Angus (21 May 2012). "Zimbabwe Rejects UN Appeal for Gay Rights, Denies Torture Claims". The Huffington Post. Harare. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ""Gambian President Says No to Aid Money Tied to Gay Rights", Voice of America, reported by Ricci Shryock, 22 April 2012". VOA. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- Boni, di Federico. "Sudan, cancellata la pena di morte per le persone omosessuali - Gay.it". www.gay.it (in Italian). Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- "African Anti-Gay Laws". Laprogressive.com. 20 February 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- "Una boda homosexual en el centro de inmigrantes de Melilla para "acabar con el miedo"". eldiario.es. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- Badrudin, Assani. "Mayotte: First gay wedding soon celebrated on the island of perfumes". Indian Ocean Times – only positive news on indian ocean. Archived from the original on 29 April 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- Planet, Lonely. "Gay and Lesbian travel in Africa – Lonely Planet". Archived from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- "Africa's most and least homophobic countries". Afrobarometer. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- Richard Parkinson: Homosexual Desire and Middle Kingdom Literature. In: The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology (JEA), vol. 81, 1995, pp. 57–76.

- Emma Brunner-Traut: Altägyptische Märchen. Mythen und andere volkstümliche Erzählungen. 10th Edition. Diederichs, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-424-01011-1, pp. 178–179.

- "Archaeological Sites". 20 October 2010. Archived from the original on 20 October 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2015.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- Nadel, S. F. "The Nuba; an anthropological study of the hill tribes in Kordofan" – via Internet Archive.

- Debele, Serawit B. (1 April 2020). "Of Taming Carnal DesireImperial Roots of Legislating Sexual Practices in Contemporary Ethiopia". History of the Present: A Journal of Critical History. 10 (1): 84–100. doi:10.1215/21599785-8221434. ISSN 2159-9785.

- Rodney Needham, Right and Left: Essays on Dual Symbol Classification, University of Chicago Press, 1973.

- "Long-Distance Trade and Foreign Contact". Uganda. Library of Congress Country Studies. December 1990. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- David Livingstone, The Last Journals of David Livingstone, in Central Africa, From 1865 to His Death, 1866–1873 Continued by a Narrative of His Last Moments and Sufferings

- Will Roscoe and Stephen O. Murray(Author, Editor, Boy-wives and Female Husbands: Studies of African Homosexualities, 2001

- Carroll, Aengus; Mendos, Lucas Ramón (May 2017). "State Sponsored Homophobia 2017: A world survey of sexual orientation laws: criminalisation, protection and recognition" (PDF). ILGA.

- "Algeria". Human Dignity Trust. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- "Algeria: Treatment of homosexuals by society and government authorities; protection available including recourse to the law for homosexuals who have been subject to ill-treatment (2005-2007)". Refworld. Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. 30 July 2007. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- Galán, José Ignacio Pichardo. "Same-sex couples in Spain. Historical, contextual and symbolic factors" (PDF). Institut national d'études démographiques. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- "Spain approves liberal gay marriage law". St. Petersburg Times. 1 July 2005. Archived from the original on 28 December 2007. Retrieved 8 January 2007.

- "Spain Intercountry Adoption Information". U. S. Department of State — Bureau of Consular Affairs. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- "Ley 14/2006, de 26 de mayo, sobre técnicas de reproducción humana asistida". Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado (in Spanish). 27 May 2006. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- "Rainbow Europe: legal situation for lesbian, gay and bisexual people in Europe" (PDF). ILGA-Europe. May 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2014.

- "Ley 3/2007, de 15 de marzo, reguladora de la rectificación registral de la mención relativa al sexo de las personas". Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado (in Spanish). 16 March 2007.

- "Reglamento regulador del Registro de Uniones de Hecho, de 11 de septiembre de 1998". Ciudad Autónoma de Ceuta (in Spanish). 11 September 1998.

- "Egypt (Law)". ILGA. Archived from the original on 11 July 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- "Libyan 'Gay' Men Face Torture, Death By Militia: Report (GRAPHIC)". HuffPost. 26 November 2012.

- Fhelboom, Reda (22 June 2015). "Less than human". Development and Cooperation.

- "Lei n.ᵒ 7/2001" (PDF). Diário da República Eletrónico (in Portuguese). 11 May 2001. Article 1, no. 1.

- "AR altera lei das uniões de facto".

- Law no. 9/2010, from 30th May.

- "Lei 17/2016 de 20 de junho".

- "Lei que alarga a procriação medicamente assistida publicada em Diário da República". tvi24. 20 June 2016.

- "Todas as mulheres com acesso à PMA a 1 de Agosto". PÚBLICO.

- "MEPs welcome new gender change law in Portugal; concerned about Lithuania - The European Parliament Intergroup on LGBTI Rights". www.lgbt-ep.eu.

- "REGLAMENTO REGULADOR DEL REGISTRO DE PAREJAS DE HECHO DE LA CIUDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MELILLA" [REGULATORY REGULATION OF THE REGISTER OF COUPLES IN FACT OF THE CIUDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MELILLA] (PDF) (in Spanish). 1 February 2008. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- "ILGA-Europe". ilga-europe.org.

- "Morocco (Law)". ilga.org. ILGA. Archived from the original on 24 July 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- Encyclopedia of Lesbian and Gay Histories and Cultures: An Encyclopedia. Gay histories and cultures. Vol. 2. Taylor & Francis. 8 November 2017. ISBN 9780815333548 – via Google Books.

- "La junta de protección a la infancia de Barcelona: Aproximación histórica y guía de su archivo" (PDF). Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- "Where is it illegal to be gay? - BBC News". Bbc.com. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- "Sudan drops death penalty for homosexuality". 76crimes.com. 15 July 2020.

- "Reforms In Sudan Result In Removal Of Death Penalty And Flogging For Same-Sex Relations". curvemag.com. 16 July 2020.

- "Tunisia (Law)". ilga.org. ILGA. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- "Tunisian presidential committee recommends decriminalizing homosexuality". NBC News. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- "Benin (Law)". ilga.org. ILGA. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- "The Gambia passes bill imposing life sentences for some homosexual acts | World news". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- "Ghana (Law)". ilga.org. ILGA. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- "Sexual Minorities: Their Treatment Across the World". Xpats.io. 11 January 2010.

- "LGBT Rights in Liberia - Equaldex". www.equaldex.com.

- "LGBT Rights in Mauritania - Equaldex". www.equaldex.com.

- "Nigeria (Law)". ilga.org. ILGA. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- "Marriage (Ascension) Ordinance, 2016" (PDF).

- Jackman, Josh (20 December 2017). "This tiny island just passed same-sex marriage". PinkNews.

- "LGBT Rights in Senegal". Equaldex.

- "Cameroonian LGBTI activist found tortured to death in home". glaad.org. 17 July 2013.

- "Décret n° 160218 du 30 mars 2016 portant promulgation de la Constitution de la République centrafricaine" (PDF). ilo.org.

- "Gabon lawmakers vote to decriminalise homosexuality". Reuters. Reuters. 24 June 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "Everything you need to know about human rights. | Amnesty International". Amnesty.org. 25 September 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- "Laws of Kenya ; The Constitution of Kenya" (PDF). Kenyaembassy.com. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- "2013 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT" (PDF). Country Reports on Human Rights Practices. 2013. p. 33.

- "Tanzania: Mixed Messages on Anti-Gay Persecution". hrw.org. 6 November 2018.

- Gettleman, Jeffrey (8 November 2017). "David Kato, Gay Rights Activist, Is Killed in Uganda" – via www.nytimes.com.

- "LGBT Rights in Eritrea - Equaldex". www.equaldex.com.

- Asokan, Ishan (16 November 2012). "A bludgeoned horn: Eritrea's abuses and 'guilt by association' policy.'". Consultancy Africa Intelligence. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- 2009-2017.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/2010/af/154345.html

- "'Don't come back, they'll kill you for being gay'". BBC NEWS. 2020.

- "LGBT Rights in Comoros - Equaldex". www.equaldex.com.

- "The Sexual Offences Bill" (PDF). mauritiusassembly.govmu.org. Government of Mauritius. 6 April 2007. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- "LGBT Rights in Mauritius - Equaldex". www.equaldex.com.

- "Africa: Outspoken activists defend continent's sexual diversity - Norwegian Council for Africa". Afrika.no. 6 August 2009. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- "Equal Opportunities Act 2008" (PDF). Ilo.org. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- "Tiny African victory: Seychelles repeals ban on gay sex". 18 May 2016.

- "Diario da Republica" (PDF) (in Portuguese).

- "Employment & labour law in Angola". Lexology. 15 September 2015.

- "Transgender Rights in Angola" (PDF).

- CNN, Kara Fox. "Botswana scraps gay sex laws in big victory for LGBTQ rights in Africa". CNN.

- "NEWS RELEASE: BOTSWANA HIGH COURT RULES IN LANDMARK GENDER IDENTITY CASE – SALC".

- "Transgender Rights in Lesotho" (PDF).

- "Where is it illegal to be gay?". 10 February 2014 – via www.bbc.com.

- "Malawi suspends anti-gay laws as MPs debate repeal | World news". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- "Mozambique Gay Rights Group Wants Explicit Constitutional Protections | Care2 Causes". Care2.com. 3 March 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- "Homosexuality Decriminalised in Mozambique". Kuchu Times. 1 June 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- Marketing, Intouch Interactive. "Sodomy law's days numbered - Geingos - Local News - Namibian Sun". www.namibiansun.com.

- "Namibia". State.gov. 4 March 2002. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- "Namibia". Lgbtnet.dk. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- "Transgender Rights in Namibia" (PDF).

- http://www.veritaszim.net/sites/veritas_d/files/Constitution%20of%20Zimbabwe%20Amendment%20%28No.%2020%29.pdf

- Page 180 Hungochani: The History of a Dissident Sexuality in Southern Africa

- Page 93 Body, Sexuality, and Gender v. 1

- Police raid headquarters of LGBT rights group. Retrieved 14 August 2012

- President Jammeh Gives Ultimatum for Homosexuals to Leave Archived 15 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Gambia News, 19 May 2008.

- Gambian president says gays a threat to human existence-20130928, Reuters, 28 September 2013.

- "Gambia's Jammeh calls gays 'vermin', says to fight like mosquitoes". Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- "Tainting love". The Economist. 11 October 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- "Gambian President Says He Will Slit Gay Men's Throats in Public Speech – VICE News". Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- "Harper lobbies Uganda on anti-gay bill", The Globe and Mail (Toronto), 29 November 2009.

- "British PM against anti-gay legislation" Archived 2 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Monitor Online, 29 November 2009

- "Uganda considers death sentence for gay sex in bill before parliament", Guardian, 29 November 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to LGBT rights. |

- African Veil – African LGBT site with news articles

- Africans and Arabs come out online, Reuters via Television New Zealand

Signare Bi Sukugn Afroqueer Reporter